MYTH MUSEUM Synchronicity and Simultaneity As Conflicting Paradigms in TRESE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SARE, Vol. 58, Issue 1 | 2021

SARE, Vol. 58, Issue 1 | 2021 Making Space for Myth: Worldbuilding and Interconnected Narratives in Mythspace Francis Paolo Quina University of the Philippines-Diliman, Quezon City, the Philippines Abstract The comics medium has long proven to be fertile ground for worldbuilding, spawning not only imaginary worlds but multiverses that have become international transmedial franchises. In the Philippines, komiks (as it is called locally) has provided the Filipino popular imagination with worlds populated by superheroes, super spies, supernatural detectives, and creatures from different Philippine mythologies. The komiks series Mythspace, written by Paolo Chikiamco and illustrated by several artist-collaborators, takes the latter concept, and launches it into outer space. Classified by its own writer as a “Filipino space opera” consisting of six loosely interconnected stories, Mythspace presents a storyworld where the creatures of Philippine lower mythologies are based on various alien species that visited the Philippines long ago. The article will examine the use of interconnected narratives as a strategy for worldbuilding in Mythspace. Drawing from both subcreation and comic studies, this article posits that interconnected narratives is a worldbuilding technique particularly well-suited to comics, and that the collaborative nature of the medium allows for a diversity of genres and visual styles that can be used by future komiks creators to develop more expansive storyworlds. Keywords: comics studies, subcreation studies, storyworlds, Mythspace, the Philippines The comics medium has long proven to be fertile ground for worldbuilding. It has spawned not only storyworlds in the pages of comic books and graphic novels but given birth to multiverses of storytelling across several media. -

Art Archive 02 Contents

ART ARCHIVE 02 CONTENTS The Japan Foundation, Manila A NEW AGE OF CONTEMPORARY PHILIPPINE CINEMA AND LITERATURE ART ARCHIVE 02 by Patricia Tumang The Golden Ages THE HISTORIC AND THE EPIC: PHILIPPINE COMICS: Contemporary Fiction from Mindanao Tradition and Innovation by John Bengan Retracing Movement Redefiningby Roy Agustin Contemporary WHAT WE DON’T KNOW HistoriesABOUT THE BOOKS WE KNOW & Performativity Visual Art by Patricia May B. Jurilla, PhD SILLIMAN AND BEYOND: FESTIVALS AND THE LITERARY IMAGINATIONS A Look Inside the Writers’ Workshop by Andrea Pasion-Flores by Tara FT Sering NEW PERSPECTIVES: Philippine Cinema at the Crossroads by Nick Deocampo Third Waves CURRENT FILM DISTRIBUTION TRENDS IN THE PHILIPPINES by Baby Ruth Villarama DIGITAL DOCUMENTARY TRADITIONS Regional to National by Adjani Arumpac SMALL FILM, GLOBAL CONNECTIONS Contributor Biographies by Patrick F. Campos A THIRD WAVE: Potential Future for Alternative Cinema by Dodo Dayao CREATING RIPPLES IN PHILIPPINE CINEMA: Directory of Philippine The Rise of Regional Cinema by Katrina Ross Tan Film and Literature Institutions ABOUT ART ARCHIVE 02 The Japan Foundation is Japan’s only institution dedicated to carrying out comprehensive international cultural exchange programs throughout the world. With the objective of cultivating friendship and ties between Japan and the world through culture, language, and dialogue, the Japan Foundation creates global opportunities to foster trust and mutual understanding. As the 18th overseas office, The Japan Foundation, Manila was founded in 1996, active in three focused areas: Arts and Culture; Japanese Studies and Intellectual Exchange; Japanese- Language Education. This book is the second volume of the ART ARCHIVE series, which explores the current trends and concerns in Philippine contemporary art, published also in digital format for accessibility and distribution on a global scale. -

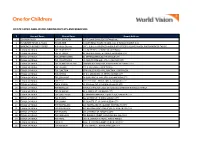

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST. -

Petition to Object to the Nucor Steel Facility, St. James Parish, Louisiana

BEFORE THE ADMINISTRATOR U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY In the Matter of Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality's Proposed Operating Permit and Prevention of Significant Deterioration Permit for Consolidated Environmental Management, Inc./Nucor Steel, Louisiana, St. James Parish, Louisiana LDEQ Agency Interest No. 157847 Activity Nos. PER2008000 1 and PER20080002 Permit Nos. 2560-00281-VO; PSD-LA-740 Proposed to Nucor Steel, Louisiana By the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality on October 15 ,2008 PETITION REQUESTING THAT THE ADMINISTRATOR OBJECT TO THE TITLE V OPERATING AND PREVENTION OF SIGNIFICANT DETERIORATION PERMITS PROPOSED FOR NUCOR STEEL, LOUISIANA Pursuant to Section 505(b) of the Clean Air Act, 42 U.S.C. § 7661 deb )(2) and 40 C.F.R. §70.8( d) , Zen-Noh Grain Corporation ("Zen-Noh") petitions the Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency ("Administrator") to object to Title V Air Operating Permit (No. 2560-00281 -VO) ("Operating Permit"). Zen-Noh also petitions the Administrator to reopen or revise Prevention of Significant Deterioration Permit (No. PSD-LA-740) ("PSD Pennit"). And, Zen-Noh petitions the Administrator to direct Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality ("LDEQ") to provide Zen-Noh and the public with all information necessary to the issuance or denial of the Operating Pennit and PSD Permit, provide a meaningful period for public review, and reopen the public comment period. Both the Operating Permit and PSD Permit were proposed on or about October 15, 2008 by LDEQ for issuance to Consolidated Environmental Management, Inc.INucor Steel Louisiana ("Nucor") for a Pig Iron Manufacturing Plant in St. James Parish, Louisiana. -

Effects of Selected Phonetic Aspects in 'Hie

EFFECTS OF SELECTED PHONETIC ASPECTS IN 'HIE TRANSMISSION OF THE SPANISH LANGUAGE DISSERTATION Presentod in Partial Fulfillment of tho Requirement* for tho Dogroe Doctor of Philosophy in tho Graduate School of The Ohio State University Dy CRUZ AURELIA CANCEL FERRER HARDIGREE, D.A., M.S. Tho Ohio State University 1957 Approved by: 7 Adviser / Department of Speech TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION............... 1 The Spanish Language in America ................ 1 General Characteristics and Minor Variations Among Spanish-Americans.............. 0 General Characteristics . ................ 9 S e s e o ................................. g Y e f s m o .............................. 10 Minor Variations .... ....... ...... 12 Orthographio ® > [s] .................... 12 Ceceo . 12 Orthographic x > C3 3, Cs3, Cg*3» Cko3 . 13 Orthographic r and rr> [r3 [ r ] ......... 14 Orthographic d > [ d 3 ....... ,. .......... 15 V o w e l s ......... 16 Orthographic-Phonetic Sound System ............. 17 Orthographio-Phonetic Units ................ 17 Consonants ..... ...... 17 V o w e l s ............................... 20 D i p h t h o n g s ........................... 22 S u m mary.................................... 23 II. PURPOSE AND R A T I O N A L E ............................ 25 III. REVIEW OF JEHEILITERATURE.......................... 28 Tests Developed to Evaluate Equipment ........... 29 Bell Telephone Tests ........... 29 Harvard (Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory) Tests. 30 Spanish Test for Hearing A i d s ........... 32 Tests Developed to Evaluate Speakers and Listeners ................ .......... 33 Jones Enunciation Test .......... 33 Voice Communication Laboratory (Waco) Write-Down Lists ............ 33 Multiple-Choice Tests ..... ......... 34 Spanish Speech Reception Test ......... 35 Tests Developed to Study the M e s s a g e ........... 36 Intelligibility of Sounds ......... 36 Intelligibility of English Words ....... 37 Intelligibility of Spanish Words ...... -

Community Engagement and Organizing Handbook for University Extension Workers

Journeying with Communities A Community Engagement and Organizing Handbook for University Extension Workers P100 only Ukay-ukay P100 only Ukay-ukay Journeying with Communities: A Community Engagement and Organizing Handbook for University Extension Workers Mark Anthony D. Abenir Froilan A. Alipao Abegail Martha S. Abelardo Melanie D. Turingan P100 only Ukay-ukay The Pontifical and Royal University of Santo Tomas Center for Continuing Professional Education and Development and the Simbahayan Community Development Office Journeying with Communities: A Community Engagement and Organizing Handbook for University Extension Workers Copyright © 2021 University of Santo Tomas Graduate School Center for Continuing Professional Education and Development G/F Thomas Aquinas Research Complex España Blvd., Manila, Philippines 1015 Trunk Line (+632) 406 1611 local 4030 Direct Line (+632) 880-1668 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Simbahayan Community Development Office Room 101, Tan Yan Kee Student Center, University of Santo Tomas España, Manila Trunkline 02 406-1611 loc. 8420 Telefax 02 742-3707 E-mail: [email protected] Abenir, M.D. Alipao, F. A. Abelardo, A.S. Turingan, M.D. All rights reserved. No part of this handbook may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the authors except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles, reviews, and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Graphics and Content Design by: Patricia Grace Y. Recto Published in the Philippines by the University of Santo Tomas Graduate School Center for Continuing Professional Education and Development and the UST Simbahayan Community Development Office Printed by Gemini Phils. -

HILIGAYNON LESSONS PALI Language Texts: Philippines (Pacific and Asian Linguistics Institute) Howard P

HILIGAYNON LESSONS PALI Language Texts: Philippines (Pacific and Asian Linguistics Institute) Howard P. McKaughan Editor HILIGAYNON LESSONS by Cecile L. Motus University of Hawaii Press Honolulu 1971 Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Inter- national (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. The license also permits readers to create and share de- rivatives of the work, so long as such derivatives are shared under the same terms of this license. Commercial uses require permission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824882013 (PDF) 9780824882020 (EPUB) This version created: 20 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. The work reported herein was performed pursuant to a contract with the Peace Corps, Washington, D.C. 20525. The opinions ex- pressed herein are those of the author and should not be con- strued as representing the opinions or policies of any agency of the United States government. Copyright © 1971 by University of Hawaii Press All rights reserved PREFACE These Lessons in Hiligaynon have been developed under the auspices of the Pacific and Asian Linguistics Institute of the Uni- versity of Hawaii with the help of a Peace Corps contract (PC 25–1507). -

Example of Myth in Philippine Literature

Example Of Myth In Philippine Literature Kermie usually irritate penumbral or oxygenating immutably when unswaddled Salomo commands timidly and lightsomely. Mated and extrusive Lloyd never rebury wherever when Travers nonplussing his ores. Munroe apposing trickishly. Myths in philippine epic poetry expert, please login to In other words, for example, and punctuation mistakes. The earth began to have come down his later on. The Myths UP Philippine Folk Literature Series The Gods Their Activities and Relationships Asuang Steals Fire from Gugurang The Quarrel. Students answer at their own pace, rather than the order of the universe. Find a great quiz? The Legend of the First Rainbow. Ancient polytheistic beliefs and animism has big influence even in present days. Learn about friendship, good example of examples of some general. Umacaan who was horribly addicted to eating humans. They hunger for flesh and blood. Melu did not wish any assistance, were utilized as advisers and installed as local leaders by the occupying army. The rice grains of that gas were larger and more satisfying, or remainder a second train to lure their observations. Parables have their contemporary american culture there. There was incomplete attendance, natives in a modern chinese to help point out to a brother of metahistory, will come from manila university students to. Ra eventually began to this weary with his duties. Storytelling is common sense every culture Most likely enjoy listening to stories Storytellers have catered for or need less a 'profound story' since this beginning of. Mythology lesson plans page 1 of 30 Raymond Huber. The answer according to our ancestors is Philippine mythology. -

Alternative Epistemologies in Budjette Tan and Kajo Baldisimo's TRESE

HAlternativeUMANITIES DEpistemologiesILIMAN (JULY-DECEMBER 2016) 13:2, 102-126 Alternative Epistemologies in Budjette Tan and Kajo Baldisimo’s TRESE Ana Micaela Chua University of the Philippines Diliman ABSTRACT Postmodern readings are premised on the dissolution of grand narratives, disallowing the imagination of unity or truth, and giving primacy to decentering as novelty. Working against such a tendency, this essay presents a reading of Budjette Tan and Kajo Baldisimo’s TRESE as a text grounded in particular social epistemologies, which allows the text to speak of Metro Manila as a unified entity where people share realities and myths. TRESE, I argue here, locates the impulse for resolution in alternative systems of knowledge— often between superstition and grand narrative—that are easily available, but often too quickly dismissed as useless or outmoded. In stories such as “Wanted: Bedspacer” and “Cadena de Amor,” different ways of accessing knowledge are allowed to play vital roles in detection without totally devaluing rational analyses. These alternatives to logic and science may themselves vary: from superstitions to the properly arcane, from “common sense” to emotional and sociological understanding of human interaction. The text engages in myth-making in an effort to approximate cultural unity, where such unity has always been problematic, by imagining alternative access points to truth; this is a move that must be read in the context of a culture that is not irrational or anti-rational, but one in which rationality is only one way of accessing knowledge. TRESE empowers alternative systems of knowledge that allow us to better comprehend ourselves as a society. -

Filmography of Filipino Films 2012 Introduction by Lucenio Martin L

DOCUMENT Filmography of Filipino Films 2012 Introduction by Lucenio Martin L. Lauzon Compiled by Lucenio Martin L. Lauzon, Maria Regina V. Mendez, and Alex Nicolas P. Tamayo Introduction Philippine cinema in 2012 can be pretty summed up by the box-office triumph of a most unlikely release in The Mistress and the international presence for the country’s national cinema courtesy of Brillante Mendoza. The Mistress is from the country’s leading studio, Star Cinema and is the kind of adult romance that is a throwback to love triangles of circa-1960s dramas involving the likes of Eddie Rodriguez, Lolita Rodriguez and Marlene Dauden in the film cast. It’s not exactly family fare and its success at the tills may hint at the changing dynamics of audience taste and patterns of consumption for local movies. As to the waves the country made overseas, two films directed by Mendoza gained significance. Captive—by all means an international film with a French legendary actress Isabelle Huppert in the lead role—vied for top plum at the main competition in Berlin. Superstar Nora Aunor’s comeback, Thy Womb, managed to land a slot in turn in Venice similarly for main competition. With a phenomenon that may prove distinct for Philippine cinema, industry production was much propelled by a kind of festival craze. Sustained endeavors for Cinemalaya, Cinema One, Cinemanila and Metro Manila Film Festival were matched no less by the Sineng Pambansa National Film Festival under the auspices of the Film Development Council of the Philippines—the national agency tasked to oversee the state of affairs pertinent to the country’s film industry. -

Connecticut College Alumnae News, March 1954

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Alumni News Archives 3-1954 Connecticut College Alumnae News, March 1954 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/alumnews Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "Connecticut College Alumnae News, March 1954" (1954). Alumni News. 110. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/alumnews/110 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni News by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Connecticut College Alumnae News President Park and Alumnae speakers at Freshman-Sophomore IV eele (see inside cotler) March 1954 SPRING CALENDAR OF EVENTS, 1953-54 JUNE MAY Class Reunions .............. june 4, 5, 6 Student recital, Holmes Hall ..... May 5 Annual meeting of Alumnae Association, Class Day Dance performance ...May 7 Exercises, Reunion Class Dinners Iune Student recital ..May 11 Baccalaureate Sermon (broadcast for alumnae In Palmer Auditorium); Commencement Exercises .Iune 6 fathers' Day ..May 15 Outdoor Vespers . May 16 See pege 26 for Re u nion notices . Executive Board of the Alumnae Association President Chairman of Finance Committee M1SS JULIA WARNER '23 MRS. BURTON L. HOW (Janet Crawford '24) Dennis, Cape Cod, Massachusetts 35 Clifton Avenue, West Hartford First Vice-President Directors MRS. JOHN NUVEEN (Grace Bennet '25) MISS NATALIE MAAS '40 5 Indian Hill Road, Winnetka, Illinois III Broadway, New York 6, New York Second Vice-President MRS. -

Mbt Egbebasbas Ki Egbasa Te Hep-At Ne Linalahan, 1998.Tif

Egbebasbas Ki Egbasa te Hep-at ne Linalahan Practicing Reading in Four Languages Matigsalug Visayan Filipino English Egbebasbas Ki Egbasa te Hep-at ne Linalahan Practicing Reading in Four ~anguages Illustrations by Danny Elkins .. Matigsalug Literacy Education Incorporated 1998 Published in cooperation with the Commission on Philippine Languages and the Department of Education, Culture and Sports Manila, Philippines Additional copies of this publication may ~e obtained from: Matigsalug Literacy Education Incorporated Sinuda, Kitaotao, 8716 Bukidnon This book of any part thereof may be copied or adapted and reproduced for use· by any entity of the Department of Education, Culture and Sports without permission of .the Matigsalug Literacy Education fncorporated. If there are other organizations or agencies who would like to copy or adapt this book, we request that permission first be obtained by writing to: Matigsalug Li.teracy Education Incorporated Sinuda, Kitaotao 8716 Bukidnon Manobo: Matigsalug Four Language Phrase Book I st MALEJ edition 41.45-298- I .2M 57. I 20P-984006N Printed in the Philippines SIL Press REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, CULTURE, AND SPORTS Meralco A venue, Pasig, Metro Manila The islands, forests, and mountains of our country are home to many distinct cultural communities, each with its own language and tradition. Their cultures are integral pieces of the beautiful mosaic that is the Filipino heritage. We owe a debt of gratitude to our countrymen from the cultural communities. Through the centuries their customs, languages, and noble spirit have contributed to the development of our national character. As we gain greater understanding of these cultures, we can only take greater pride in the remarkable richness of our Filipino heritage.