Vincenzo Scamozzi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libraries: Architecture and the Ordering of Knowledge

Libraries: Architecture and the Ordering of Knowledge English text of March 29, 2009, by J. Connors for “Biblioteche: l’architettura e l’ordinamento del sapere,” with Angela Dressen, in Il Rinascimento Italiano e l’Europa, vol. 6, Luoghi, spazi, architetture, ed. Donatella Calabi and Elena Svalduz, Treviso-Costabissara, 2010, pp. 199-228. All the texts describing ancient libraries had been rediscovered by the mid-Quattrocento. Humanists knew Greek and Roman libraries from the accounts in Strabo, Varro, Seneca, and especially Suetonius, himself a former prefect of the imperial libraries. From Pliny everyone knew that Asinius Pollio founded the first public library in Rome, fulfilling the unrealized wish of Juliuys Caesar ("Ingenia hominum rem publicam fecit," "He made men's talents public property"). From Suetonius it was known that Augustus founded two libraries, one in the Porticus Octaviae, and another, for Greek and Latin books, in the temple of Apollo on the Palatine, where the sculptural decoration included not only a colossal statue of Apollo but also portraits of celebrated writers. The texts spoke frequently of author portraits, and also of the wealth and splendor of ancient libraries. The presses for the papyrus rolls were made of ebony and cedar; the architectural order and the revetments of the rooms were of marble; the sculpture was of gilt bronze. Boethius added that libraries were adorned with ivory and glass, while Isidore mentioned gilt ceilings and restful green cipollino floors. Senecan disapproval of ostentatious libraries, of "studiosa luxuria," of piling up more books than one could ever read, gave way to admiration for magnificent libraries. -

OGGETTO: Venezia – Ex Palazzo Reale

MINISTERO PER I BENI E LE ATTIVITA’ CULTURALI DIREZIONE REGIONALE PER I BENI CULTURALI E PAESAGGISTICI DEL VENETO Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici e Paesaggistici di Venezia e Laguna Palazzo Ducale, 1 V e n e z i a PERIZIA DI SPESA N. 23 del 2 luglio 2012 D.P.C.M. 10 Dicembre 2010 di ripartizione della quota dell’otto per mille dell’IRPEF a diretta gestione statale per l’anno 2010 RELAZIONE STORICA E RELAZIONE TECNICA CON CRONOPROGRAMMA VENEZIA – PIAZZA SAN MARCO LAVORI DI CONSERVAZIONE DELLA FACCIATA, DEL PORTICO E DELLE COPERTURE DELLE PROCURATIE NUOVE – Campate XI – XXXVI C.U.I. 13854 CUP F79G10000330001 Venezia, 2 LUGLIO 2012 IL PROGETTISTA Visto:IL SOPRINTENDENTE Arch. Ilaria Cavaggioni arch. Renata Codello IL RESPONSABILE DEL PROCEDIMENTO Arch. Anna Chiarelli Venezia - Procuratie Nuove o Palazzo Reale Intervento di conservazione della facciata principale e dalla falda di copertura (…) guardatevi dal voler comparire sopra le cose fatte: accomodatele, assicuratele, ma non aggiungete, non mutilate, e non fate il bravo. Giuseppe Valdier L’Architettura Pratica, III, p. 115 Relazione illustrativa con cenni sulla storia della fabbrica SOMMARIO 1. Introduzione 2. Cenni sulla storia della fabbrica 3. Caratteri stilistici 4. Caratteri costruttivi 5. La ricerca d’archivio 6. Stato di conservazione 7. Descrizione dell’intervento: linee guida e tecniche 8. Riferimenti bibliografici 1. Introduzione Molti degli aspetti descritti in questa relazione, relativi alla vicenda storica della fabbrica delle Procuratie Nuove, alle caratteristiche stilistiche e costruttive della facciata principale del palazzo, al suo stato di conservazione, ecc., si basano su ipotesi fondate sull’osservazione a distanza, ai piedi della fabbrica, sulla letteratura artistica consultata, su precedenti restauri documentati, su analogie con le Progetto definitivo 2 Venezia - Procuratie Nuove o Palazzo Reale Intervento di conservazione della facciata principale e dalla falda di copertura fabbriche coeve, sulle raccomandazioni dei manuali storici, ecc. -

Discover Padua and Its Surroundings

2647_05_C415_PADOVA_GB 17-05-2006 10:36 Pagina A Realized with the contribution of www.turismopadova.it PADOVA (PADUA) Cittadella Stazione FS / Railway Station Porta Bassanese Tel. +39 049 8752077 - Fax +39 049 8755008 Tel. +39 049 9404485 - Fax +39 049 5972754 Galleria Pedrocchi Este Tel. +39 049 8767927 - Fax +39 049 8363316 Via G. Negri, 9 Piazza del Santo Tel. +39 0429 600462 - Fax +39 0429 611105 Tel. +39 049 8753087 (April-October) Monselice Via del Santuario, 2 Abano Terme Tel. +39 0429 783026 - Fax +39 0429 783026 Via P. d'Abano, 18 Tel. +39 049 8669055 - Fax +39 049 8669053 Montagnana Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 Castel S. Zeno Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 Tel. +39 0429 81320 - Fax +39 0429 81320 (sundays opening only during high season) Teolo Montegrotto Terme c/o Palazzetto dei Vicari Viale Stazione, 60 Tel. +39 049 9925680 - Fax +39 049 9900264 Tel. +39 049 8928311 - Fax +39 049 795276 Seasonal opening Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 nd TREVISO 2 Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 AIRPORT (sundays opening only during high season) MOTORWAY EXITS Battaglia Terme TOWNS Via Maggiore, 2 EUGANEAN HILLS Tel. +39 049 526909 - Fax +39 049 9101328 VENEZIA Seasonal opening AIRPORT DIRECTION TRIESTE MOTORWAY A4 Travelling to Padua: DIRECTION MILANO VERONA MOTORWAY A4 AIRPORT By Air: Venice, Marco Polo Airport (approx. 60 km. away) By Rail: Padua Train Station By Road: Motorway A13 Padua-Bologna: exit Padua Sud-Terme Euganee. Motorway A4 Venice-Milano: exit Padua Ovest, Padua Est MOTORWAY A13 DIRECTION BOLOGNA adova. -

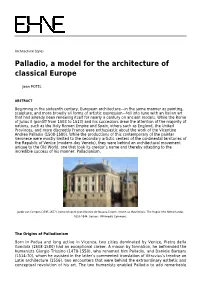

Palladio, a Model for the Architecture of Classical Europe

Architectural Styles Palladio, a model for the architecture of classical Europe Jean POTEL ABSTRACT Beginning in the sixteenth century, European architecture—in the same manner as painting, sculpture, and more broadly all forms of artistic expression—fell into tune with an Italian art that had already been renewing itself for nearly a century on ancient models. While the Rome of Julius II (pontiff from 1503 to 1513) and his successors drew the attention of the majority of nations, such as the Holy Roman Empire and Spain, others such as England, the United Provinces, and more discreetly France were enthusiastic about the work of the Vicentine Andrea Palladio (1508-1580). While the productions of this contemporary of the painter Veronese were mostly limited to the secondary artistic centers of the continental territories of the Republic of Venice (modern-day Veneto), they were behind an architectural movement unique to the Old World, one that took its creator’s name and thereby attesting to the incredible success of his manner: Palladianism. Jacob van Campen (1595-1657), home of count Jean-Maurice de Nassau-Siegen, known as Mauritshuis, The Hague (the Netherlands), 1633-1644. Source : Wikimedia Commons. The Origins of Palladianism Born in Padua and long active in Vicenza, two cities dominated by Venice, Pietro della Gondola (1508-1580) had an exceptional career. A mason by formation, he befriended the humanists Giorgio Trissino (1478-1550), who renamed him Palladio, and Daniele Barbaro (1514-70), whom he assisted in the latter’s commented translation of Vitruvius’s treatise on Latin architecture (1556), two encounters that were behind the extraordinary esthetic and conceptual revolution of his art. -

Palladio and Vitruvius: Composition, Style, and Vocabulary of the Quattro Libri

LOUIS CELLAURO Palladio and Vitruvius: composition, style, and vocabulary of the Quattro Libri Abstract After a short preamble on the history of the text of Vitruvius during the Renaissance and Palladio’s encounter with it, this paper assesses the Vitruvian legacy in Palladio’s treatise, in focusing more particularly on its composition, style, and vocabulary and leaving other aspects of his Vitruvianism, such as his architectural theory and the five canonical orders, for consideration in subsequent publications. The discussion on composition concerns Palladio’s probable plans to complete ten books, as an explicit reference to Vitruvius’ treatise. As regards style, the article highlights Palladio’s intention to produce an illustrated treatise like those of Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Sebastiano Serlio, and Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola (whereas the treatise of Vitruvius was probably almost unillustrated), and Palladio’s Vitruvian stress on brevity. Palladio is shown to have preferred vernacular technical terminology to the Vitruvian Greco-Latin vocabulary, except in Book IV of the Quattro Libri in connection with ancient Roman temples. The composition, style, and vocabulary of the Quattro Libri are important issues which contribute to an assessment of the extent of Palladio’s adherence to the Vitruvian prototype in an age of imitation of classical literary models. Introduction The De architectura libri X (Ten Books on Architecture) of the 1st-Century BCE Roman architect and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio was a text used by Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) and many other Renaissance architects both as a guide to ancient architecture and as a source of modern design. Vitruvius is indeed of great significance for Renaissance architecture, as his treatise can be considered as a founding document establishing the ground rules of the discipline for generations after its first reception in the Trecento and early Quattrocento.1 His text offers a comprehensive overview of architectural practice and the education required to pursue it successfully. -

The Thin White Line: Palladio, White Cities and the Adriatic Imagination

Chapter � The Thin White Line: Palladio, White Cities and the Adriatic Imagination Alina Payne Over the course of centuries, artists and architects have employed a variety of means to capture resonant archaeological sites in images, and those images have operated in various ways. Whether recording views, monuments, inscrip- tions, or measurements so as to pore over them when they came home and to share them with others, these draftsmen filled loose sheets, albums, sketch- books, and heavily illustrated treatises and disseminated visual information far and wide, from Europe to the margins of the known world, as far as Mexico and Goa. Not all the images they produced were factual and aimed at design and construction. Rather, they ranged from reportage (recording what there is) through nostalgic and even fantastic representations to analytical records that sought to look through the fragmentary appearance of ruined vestiges to the “essence” of the remains and reconstruct a plausible original form. Although this is a long and varied tradition and has not lacked attention at the hands of generations of scholars,1 it raises an issue fundamental for the larger questions that are posed in this essay: Were we to look at these images as images rather than architectural or topographical information, might they emerge as more than representations of buildings, details and sites, measured and dissected on the page? Might they also record something else, something more ineffable, such as the physical encounters with and aesthetic experience of these places, elliptical yet powerful for being less overt than the bits of carved stone painstakingly delineated? Furthermore, might in some cases the very material support of these images participate in translating this aesthetic 1 For Italian material the list is long. -

00 Prelims 1630

02 Howard 1630 13/11/08 11:01 Page 29 ITALIAN LECTURE Architectural Politics in Renaissance Venice DEBORAH HOWARD St John’s College, Cambridge WHATISTHE ROLE OF ARCHITECTURE in the self-definition of a political regime? To what extent are the ideologies of state communicated in public space? Can public confidence be sustained by extravagant building initiatives—or be sapped by their failures? These issues are, of course,as relevant today as they were in the Renaissance.Venice,in particular,seems closer to our own times than most other Early Modern states because of its relatively ‘democratic’ constitution, at least within the ranks of the rul- ing oligarchy. It was a democracy only for noblemen, since voting rights and eligibility for important committees and councils were limited to members (men only, numbering about 2,000) of a closed, hereditary caste. Nevertheless,many of the problems over decision-making ring true to modern ears.Indeed, it could be argued that the continual revision of public building projects during their execution is an essential characteristic of the democratic process. It has been claimed by architectural historians over the past few decades that ambitious programmes of building patronage in Renaissance Venice helped to communicate political ideals to the public.1 Read at the Academy 10 May 2007. 1 See,for example,Manfredo Tafuri, Jacopo Sansovino (Padua, 1969; 2nd edn., 1972); Deborah Howard, Jacopo Sansovino: Architecture and Patronage in Renaissance Venice (New Haven & London, 1975; rev.edn., 1987); Manfredo Tafuri, ‘“Renovatio urbis Venetiarum”: il problema storiografico’, in M. Tafuri (ed.), ‘Renovatio urbis’: Venezia nell’età di Andrea Gritti (1523–1538) (Rome,1984), pp.9–55; Manfredo Tafuri, Venezia e il Rinascimento (Turin, 1985; English edn., trans.Jessica Levine,Cambridge,MA and London, 1989). -

The Magical Light of Venice

The Magical Light of Venice Eighteenth Century View Paintings The Magical Light of Venice Eighteenth Century View Paintings The Magical Light of Venice Eighteenth Century View Paintings Lampronti Gallery - London 30 November 2017 - 15 January 2018 10.00 - 18.00 pm Catalogue edited by Acknowledgements Marcella di Martino Alexandra Concordia, Barbara Denipoti, the staff of Itaca Transport and staff of Simon Jones Superfright Photography Mauro Coen Matthew Hollow Designed and printed by De Stijl Art Publishing, Florence 2017 www.destijlpublishing.it LAMPRONTI GALLERY 44 Duke Street, St James’s London SW1Y 6DD Via di San Giacomo 22 00187 Roma On the cover: [email protected] Giovanni Battista Cimaroli, The Celebrations for the Marriage of the Dauphin [email protected] of France with the Infanta Maria Teresa of Spain at the French Embassy in www.cesarelampronti.com Venice in 1745, detail. his exhibition brings together a fine selection of Vene- earlier models through their liveliness of vision and master- T tian cityscapes, romantic canals and quality of light ful execution. which have never been represented with greater sensitivity Later nineteenth-century painters such as Bison and Zanin or technical brilliance than during the wondrous years of reveal the profound influence that Canaletto and his rivals the eighteenth century. had upon future generations of artists. The culture of reci- The masters of vedutismo – Canaletto, Marieschi, Bellot- procity between the Italian Peninsula and England during to and Guardi – are all included here, represented by key the Grand Siècle, epitomised by the relationship between works that capture the essence and sheer splendour of Canaletto and Joseph Consul Smith, is a key aspect of the Venice. -

ANDREW HOPKINS and ARNOLD WITTE from Deluxe

ANDREW HOPKINS AND ARNOLD WITTE From deluxe architectural book to builder's manual: the Dutch editions of Scamozzi's L'Idea della Architettura Universale Vincenzo Scamozzi's treatise L'Idea della Architettura Universale was first published in Venice in 1615 as a large and expensive, deluxe folio edition.' Following in the footsteps of Serlio and Palladio, Scamozzi's work was profusely illustrated with plans and elevations of various edifices and included an extensive treat- ment of the orders of architecture, which described the five canonical forms of columns, as well as recording some of his own buildings. His intention to write ten books also linked Scamozzi's work to the earlier architectural treatises of Vitruvius and Alberti. The high cultural tone of L'Idea, with its masses of eru- dite classical knowledge, was matched by the dedications of the six published books to leading European rulers.? Yet, subsequent translations of Scamozzi's treatise present a work largely shorn of its erudition and transformed into what was essentially a builder's or craftsman's manual. This change was brought about in Holland in the middle of the seventeenth century in the context of rival Dutch editions of Scamozzi's treatise: one a deluxe architectural book, the second i V. Scamozzi, L'Idea dellaarchitettura universale di TlincenzoScamozzi architetto veneto divisa in X libri (Venice 1615).Folio. In two parts. Editio princeps. Printer, Giorgio Valentino. All further refer- ences to the first edition, with Book and page numbers will be indicated as follows 1615: III, p. 25. For Scamozzi's life and work see T. -

Andrea Palladio's Influence on Venetian

ANDREA PALLADIO'S INFLUENCE ON VENETIAN CHURCH DESIGN: 1581 - 1751 By RICHARD JAMES GREEN B.A. (Honours), The University of Saskatchewan, 1975 B. Arch., The University of British Columbia, 1980 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (School of Architecture) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 1987 ©Richard James Green, 1987 k In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of dst^/~j£e^&<^K. The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date Q^t>-C-c^ /S( /9gft- . DE-6G/81) ABSTRACT Andrea Palladia was born in Padua in the Republic of Venice in 1508 and practiced his architecture throughout the Veneto until his death in 1580. Today, there are some forth-four surviving palaces, villas, and churches by the master. These buildings have profoundly moved the imagination of countless generations of academics, artists, and architects for over four hundred years. Without a doubt, he has been the most exalted and emulated architect in modern history. -

Quest of an Appropriate Antiquity: the Arena of Verona and Its Influence on Architectural Theory in the Early Modem Era

Originalveröffentlichung in: Enenkel, Karl A. E. ; Ottenheym, Konrad A. (Hrsgg.): The quest for an appropriate past in literature, art and architecture. Leiden 2019, S. 76-105 (Intersections : interdisciplinary studies in early modern culture ; 60) CHAPTER 3 A City in Quest of an Appropriate Antiquity: The Arena of Verona and Its Influence on Architectural Theory in the Early Modem Era Hubertus Gunther Some curious observations led me to the argument of this contribution. Firstly, in Sebastiano Serlio’s book on Roman antiquities - precisely, in its second edition -1 found the comment on the Arena of Pola that the manner of this articulation is obviously very different from those used in Rome, and Ifor my part would not adopt members such as those of the Amphitheatre in Rome in my works, but would willingly avail my self of those of the building in Pola, as they are done in a better manner and are better conceived, and I am sure that this was done by a different architect and that by chance he [i.e. the one of the Coliseum] he was a German, because the members of the Coliseum have something of the German manner.1 ‘German manner’ (maniera tedesca) was the usual term for the style of me dieval buildings generally despised in Italy at that time, and German in this context means Germanic. As was well known in the Renaissance, the Roman amphitheatre called the Colosseum had been built under Vespasian some ten years before Tacitus wrote his famous account of the Germanic tribes, report ing that they still lived in wooden huts spread out between large forests. -

Vincenzo Scamozzi Comments on the Architectural Treatise of Sebastiano Serlio

Originalveröffentlichung in: Annali di architettura : rivista del Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura Andrea Palladio 27.2015 (2016), S. 47-60 Hubertus Giinther Vincenzo Scamozzi comments on the architectural treatise of Sebastiano Serlio in Paris where it was offered by Bonnefoi Livres Anciens and thereupon the Ernst von Siemens Foundation has acquired it for the Zentralinsti- tut fiir Kunstgeschichte in Munich 1. It attracts particular interest as Scamozzi has edited the treatise of Serlio. Serlio published his treatise gradually in in- dividual books2. The work had a huge success. It appeared in many editions and various languag- es throughout Europe. First were printed the two crucial books, both by Francesco Marcoli- ni in Venice: in 1537 the doctrine of the orders of columns as the Fourth Book and in 1540 the presentation of ancient buildings in Rome and throughout Italy as Third Book. The columns doctrine remained instrumental until the early 20th century, although it had been modified in details and the principles on which it is based had changed. The book on ancient buildings re- mained unique up to 1682 when Antoine Desgo- detz had published Les e'difices antiques de Rome on behalf of the French Academy. After Serlio had left Venice and entered the service of the king of France, appeared in Paris three smaller books on the geometric basics of architecture, perspective and church design. In 1551 the Venetian pub- lisher Cornelio Nicolini launched the five books hitherto published in a representative collection in folio format - as was the original format. The publisher has changed hardly anything on the books; the old title pages and dedications are maintained; there is not even a special preface or a dedication.