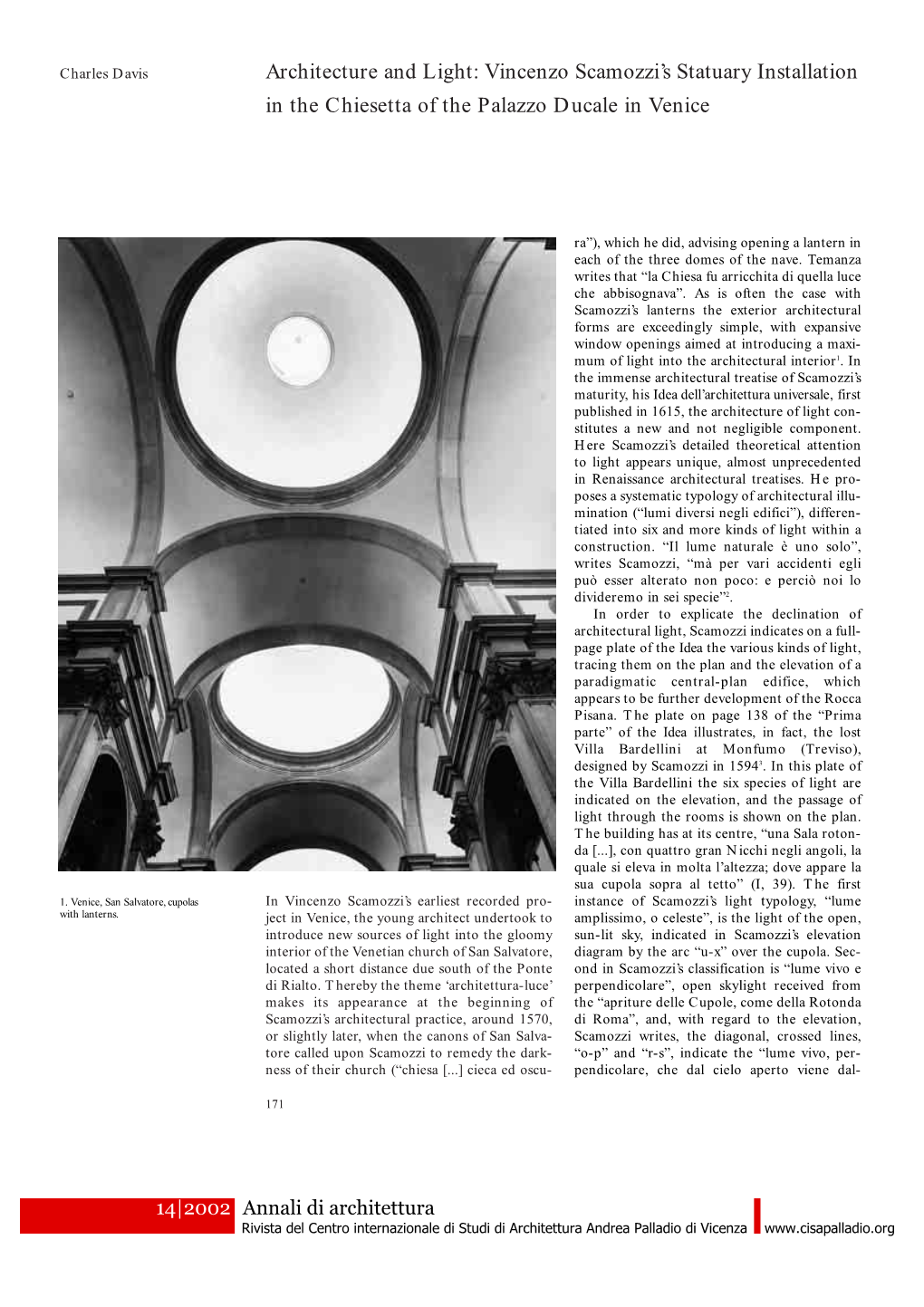

Saggio Davis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rudolf Wittkower and Architectural Principles in the Age of Modernism Author(S): Alina A

Rudolf Wittkower and Architectural Principles in the Age of Modernism Author(s): Alina A. Payne Source: The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Sep., 1994), pp. 322-342 Published by: Society of Architectural Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/990940 Accessed: 15/10/2009 16:45 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sah. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society of Architectural Historians is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. http://www.jstor.org Rudolf Wittkower and Architectural Principles in the Age of Modernism ALINA A. -

Architecture and the City in Humanist Urban Culture – the Case of Venice

Proceedings of the 11th Space Syntax Symposium #104 CITY-CRAFT AND STATECRAFT: Architecture and the City in Humanist Urban Culture – the case of Venice SOPHIA PSARRA UCL, London, United Kingdom [email protected] ABSTRACT Architecture is defined by intentional design, while cities are the product of multiple human actions over a long period of time. This seems to confine us between a view of architecture as authored object and a view of the city as authorless socio-economic process. This debate goes back to the separation of architecture from its skill base in building craft that took place in the Renaissance, including its division from the processes by which cities are produced by clients, users, regulatory codes, markets and infrastructures. As a result, architecture is confined in exceptional cases to the status of iconic buildings, or more generally to the status of buildings as economic production. Currently, buildings and cities are appropriated by digital technology and ubiquitous computing as a way of managing the city’s assets. Digital technologies integrate designing with making, informational models of buildings with geographic information systems and digital mapping. What had to be separated from city-making practices in order to raise architecture to a different status is increasingly re-integrated through digital infrastructure. As for architecture, traditionally engaged with the design of objects rather than networks or systems, is deprived of relevance in shaping social capital, politically and intellectually sidelined. Focusing on the Piazza San Marco in relationship to the urban fabric of Venice this paper traces the interlocking spheres of self-conscious architecture, the institutional and intellectual resources mobilised by Venetian statecraft and the networked spaces of everyday action. -

ART HISTORY of VENICE HA-590I (Sec

Gentile Bellini, Procession in Saint Mark’s Square, oil on canvas, 1496. Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice ART HISTORY OF VENICE HA-590I (sec. 01– undergraduate; sec. 02– graduate) 3 credits, Summer 2016 Pratt in Venice––Pratt Institute INSTRUCTOR Joseph Kopta, [email protected] (preferred); [email protected] Direct phone in Italy: (+39) 339 16 11 818 Office hours: on-site in Venice immediately before or after class, or by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION On-site study of mosaics, painting, architecture, and sculpture of Venice is the primary purpose of this course. Classes held on site alternate with lectures and discussions that place material in its art historical context. Students explore Byzantine, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque examples at many locations that show in one place the rich visual materials of all these periods, as well as materials and works acquired through conquest or collection. Students will carry out visually- and historically-based assignments in Venice. Upon return, undergraduates complete a paper based on site study, and graduate students submit a paper researched in Venice. The Marciana and Querini Stampalia libraries are available to all students, and those doing graduate work also have access to the Cini Foundation Library. Class meetings (refer to calendar) include lectures at the Università Internazionale dell’ Arte (UIA) and on-site visits to churches, architectural landmarks, and museums of Venice. TEXTS • Deborah Howard, Architectural History of Venice, reprint (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003). [Recommended for purchase prior to departure as this book is generally unavailable in Venice; several copies are available in the Pratt in Venice Library at UIA] • David Chambers and Brian Pullan, with Jennifer Fletcher, eds., Venice: A Documentary History, 1450– 1630 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001). -

Libraries: Architecture and the Ordering of Knowledge

Libraries: Architecture and the Ordering of Knowledge English text of March 29, 2009, by J. Connors for “Biblioteche: l’architettura e l’ordinamento del sapere,” with Angela Dressen, in Il Rinascimento Italiano e l’Europa, vol. 6, Luoghi, spazi, architetture, ed. Donatella Calabi and Elena Svalduz, Treviso-Costabissara, 2010, pp. 199-228. All the texts describing ancient libraries had been rediscovered by the mid-Quattrocento. Humanists knew Greek and Roman libraries from the accounts in Strabo, Varro, Seneca, and especially Suetonius, himself a former prefect of the imperial libraries. From Pliny everyone knew that Asinius Pollio founded the first public library in Rome, fulfilling the unrealized wish of Juliuys Caesar ("Ingenia hominum rem publicam fecit," "He made men's talents public property"). From Suetonius it was known that Augustus founded two libraries, one in the Porticus Octaviae, and another, for Greek and Latin books, in the temple of Apollo on the Palatine, where the sculptural decoration included not only a colossal statue of Apollo but also portraits of celebrated writers. The texts spoke frequently of author portraits, and also of the wealth and splendor of ancient libraries. The presses for the papyrus rolls were made of ebony and cedar; the architectural order and the revetments of the rooms were of marble; the sculpture was of gilt bronze. Boethius added that libraries were adorned with ivory and glass, while Isidore mentioned gilt ceilings and restful green cipollino floors. Senecan disapproval of ostentatious libraries, of "studiosa luxuria," of piling up more books than one could ever read, gave way to admiration for magnificent libraries. -

Vincenzo Scamozzi

Vincenzo Scamozzi Nato: nel 1552 a Vicenza - Morto: 7 agosto 1616 a Venezia Formazione: dopo una prima educazione ricevuta a Vicenza dal padre Giandomenico, imprenditore edile benestante di origini valtellinesi culturalmente legato a Sebastiano Serlio, nel 1572 si stabilì a Venezia, dove studiò il trattato di Vitruvio nell’interpretazione di Daniele Barbaro e di Andrea Palladio, deducendone un linguaggio architettonico del tutto personale che si valeva di principi metodologici basati su ragione e scienza. Sui suoi principi architettonici egli scrisse un trattato, Dell’idea di architettura universale, (Venezia1591-1615). Nel 1578 soggiornò per la prima volta a Roma,dedicandosi allo studio e al rilievo dei monumenti antichi. Tornato a Vicenza, in collaborazione con il padre realizzò una serie di palazzi e ville nella città natale e nella provincia, lavorando inoltre al completamento di alcune opere di Palladio. Progettò a Vicenza il Palazzo Godi (1569), molto alterato nell’esecuzione postuma, Villa Verlato a Villa verla (VI) (1574), costruì a Lonigo (VI) la Villa detta Rocca Pisana (1576) e a Vicenza Palazzo Trissino (1577-79). Ripresa l’attività a Venezia, costruì, continuando la libreria di S. Marco, iniziata da Sansovino, le Procuratie Nuove (1582-85 fino alla decima arcata) e, dopo la morte di Palladio, condusse a compimento a Vicenza il Teatro Olimpico, di cui realizzò anche l’apparato scenico seguendo i principi di Sebastiano Serlio e che ebbe un seguito nella progettazione del teatro di Sabbioneta (1588-1590). Dello stesso periodo sono due progetti per il Ponte di Rialto a Venezia (1588), mentre intorno al 1606 fornì i disegni per il duomo e il palazzo arcivescovile di Salisburgo. -

OGGETTO: Venezia – Ex Palazzo Reale

MINISTERO PER I BENI E LE ATTIVITA’ CULTURALI DIREZIONE REGIONALE PER I BENI CULTURALI E PAESAGGISTICI DEL VENETO Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici e Paesaggistici di Venezia e Laguna Palazzo Ducale, 1 V e n e z i a PERIZIA DI SPESA N. 23 del 2 luglio 2012 D.P.C.M. 10 Dicembre 2010 di ripartizione della quota dell’otto per mille dell’IRPEF a diretta gestione statale per l’anno 2010 RELAZIONE STORICA E RELAZIONE TECNICA CON CRONOPROGRAMMA VENEZIA – PIAZZA SAN MARCO LAVORI DI CONSERVAZIONE DELLA FACCIATA, DEL PORTICO E DELLE COPERTURE DELLE PROCURATIE NUOVE – Campate XI – XXXVI C.U.I. 13854 CUP F79G10000330001 Venezia, 2 LUGLIO 2012 IL PROGETTISTA Visto:IL SOPRINTENDENTE Arch. Ilaria Cavaggioni arch. Renata Codello IL RESPONSABILE DEL PROCEDIMENTO Arch. Anna Chiarelli Venezia - Procuratie Nuove o Palazzo Reale Intervento di conservazione della facciata principale e dalla falda di copertura (…) guardatevi dal voler comparire sopra le cose fatte: accomodatele, assicuratele, ma non aggiungete, non mutilate, e non fate il bravo. Giuseppe Valdier L’Architettura Pratica, III, p. 115 Relazione illustrativa con cenni sulla storia della fabbrica SOMMARIO 1. Introduzione 2. Cenni sulla storia della fabbrica 3. Caratteri stilistici 4. Caratteri costruttivi 5. La ricerca d’archivio 6. Stato di conservazione 7. Descrizione dell’intervento: linee guida e tecniche 8. Riferimenti bibliografici 1. Introduzione Molti degli aspetti descritti in questa relazione, relativi alla vicenda storica della fabbrica delle Procuratie Nuove, alle caratteristiche stilistiche e costruttive della facciata principale del palazzo, al suo stato di conservazione, ecc., si basano su ipotesi fondate sull’osservazione a distanza, ai piedi della fabbrica, sulla letteratura artistica consultata, su precedenti restauri documentati, su analogie con le Progetto definitivo 2 Venezia - Procuratie Nuove o Palazzo Reale Intervento di conservazione della facciata principale e dalla falda di copertura fabbriche coeve, sulle raccomandazioni dei manuali storici, ecc. -

Discover Padua and Its Surroundings

2647_05_C415_PADOVA_GB 17-05-2006 10:36 Pagina A Realized with the contribution of www.turismopadova.it PADOVA (PADUA) Cittadella Stazione FS / Railway Station Porta Bassanese Tel. +39 049 8752077 - Fax +39 049 8755008 Tel. +39 049 9404485 - Fax +39 049 5972754 Galleria Pedrocchi Este Tel. +39 049 8767927 - Fax +39 049 8363316 Via G. Negri, 9 Piazza del Santo Tel. +39 0429 600462 - Fax +39 0429 611105 Tel. +39 049 8753087 (April-October) Monselice Via del Santuario, 2 Abano Terme Tel. +39 0429 783026 - Fax +39 0429 783026 Via P. d'Abano, 18 Tel. +39 049 8669055 - Fax +39 049 8669053 Montagnana Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 Castel S. Zeno Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 Tel. +39 0429 81320 - Fax +39 0429 81320 (sundays opening only during high season) Teolo Montegrotto Terme c/o Palazzetto dei Vicari Viale Stazione, 60 Tel. +39 049 9925680 - Fax +39 049 9900264 Tel. +39 049 8928311 - Fax +39 049 795276 Seasonal opening Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 nd TREVISO 2 Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 AIRPORT (sundays opening only during high season) MOTORWAY EXITS Battaglia Terme TOWNS Via Maggiore, 2 EUGANEAN HILLS Tel. +39 049 526909 - Fax +39 049 9101328 VENEZIA Seasonal opening AIRPORT DIRECTION TRIESTE MOTORWAY A4 Travelling to Padua: DIRECTION MILANO VERONA MOTORWAY A4 AIRPORT By Air: Venice, Marco Polo Airport (approx. 60 km. away) By Rail: Padua Train Station By Road: Motorway A13 Padua-Bologna: exit Padua Sud-Terme Euganee. Motorway A4 Venice-Milano: exit Padua Ovest, Padua Est MOTORWAY A13 DIRECTION BOLOGNA adova. -

Ms Coll\Wittkower Wittkower, Rudolf. Papers, [Ca. 1923J-1978. 19.5

Ms Coll\Wittkower Wittkower, Rudolf. Papers, [ca. 1923J-1978. 19.5 linear ft. (ca. 23,200 items in 45 boxes, 8 card files) Biography: Rudolf Wittkower (1901-1971) was professor of art history at Columbia University, 1956-1969. Summary: Working files of Wittkower, dealing with Baroque and Renaissance painting, sculpture, and architecture. Included are manuscripts, notes, drawings, annotated proofs of articles and books, and some correspondence related to his writings and lectures. The majority of the files document his teaching, research, and writing at the University of London, 1934-1955, and at Columbia University. There also are some manuscript notes from his early years in Italy and Germany. Series I has been divided into six parts: Artists, Subjects, Book Manuscripts, Proofs, Notes, and Printed Materials. Some of the major files are Bernini, Bramante, Carracci, Michelangelo, and Raphael (Artists); Baroque Painting, Patronage, Rome, St. Peter's, Slade Lectures on the history of art (Subjects); Art and Architecture in Italy, Born under Saturn, and Matthews Lectures: Gothic vs. Classic (Book Manuscripts). In addition there are proofs of essays and reviews with manuscript corrections and emendations, copies of several of his own published works with his manuscript corrections, and typescript insertions for new editions. The Notes consist of eight card file boxes with notes chiefly relating to the Baroque period and Bernini. In Series I the contents of the parts overlap. For example, material relating to Bernini can be found in Artists, in Subjects under Rome and St. Peter's, and in Notes. Series II consists of manuscripts, typescripts, notes, galleys, and corrected page proofs of Wittkower's lectures and articles on Renaissance and Baroque sculpture and architecture, which were edited posthumously by Margot Wittkower for inclusion in Sculpture: Process and Principle (1977) and The Collected Essays of Rudolf Wittkower (1978). -

Best of ITALY

TRUTH IN TRAVEL TRUTH IN TRAVEL Best of ITALY VENICE & THE NORTH PAGE S 2–9 Venice Milan VENICE NORTHERN The Prince of Venice ITALY Viewing Titian’s paintings in their original basilicas and palazzi reveals a Venice of courtesans and intrigue. Pulitzer Prize—winning critic Manuela Hoelterhoff’s walking guide to the city amplifies the experience of reliving the tumultuous times of Florence the Old Master—and finds some aesthetically pleasing hotels and restaurants along the way. TUSCANY (Trail of Glory map on page 5) FLORENCE & TUSCANY PAGE S 10 –1 5 Best of ITALYCENTRAL ITALY TUSCAN COAST Rome Tuscany by the Sea Believe it or not, Tuscany has a shoreline—145 miles of it, with ports large and small, hidden beaches, a rich wildlife preserve, and, of course, the blessings of the Italian table. Clive Irving Naples discovers a sexy combo of coast, cuisine, and Pompeii Caravaggio—and customizes a beach-by-beach, Capri harbor-by-harbor map for seaside fun. SARDINIA SOUTHERN ITALY ROME & CENTRAL ITALY PAGE S 16–2 0 ROME Treasures of the Popes You’re in Rome, but the Vatican is a city in itself. (In fact, a nation.) What should you see? John Palermo Julius Norwich picks his masterpieces, and warns of the potency of Vatican hospitality. SICILY VENICE & THE NORTH PAGE 2 Two miles long, spanned by three bridges and six gondola ferries, the Grand Canal is an avenue of palaces built between the fourteenth and eigh- teenth centuries. A rich, luminous city, her beauty reflected at every turn, Venice was the perfect muse for an ambitious Renaissance artist. -

Palladio, a Model for the Architecture of Classical Europe

Architectural Styles Palladio, a model for the architecture of classical Europe Jean POTEL ABSTRACT Beginning in the sixteenth century, European architecture—in the same manner as painting, sculpture, and more broadly all forms of artistic expression—fell into tune with an Italian art that had already been renewing itself for nearly a century on ancient models. While the Rome of Julius II (pontiff from 1503 to 1513) and his successors drew the attention of the majority of nations, such as the Holy Roman Empire and Spain, others such as England, the United Provinces, and more discreetly France were enthusiastic about the work of the Vicentine Andrea Palladio (1508-1580). While the productions of this contemporary of the painter Veronese were mostly limited to the secondary artistic centers of the continental territories of the Republic of Venice (modern-day Veneto), they were behind an architectural movement unique to the Old World, one that took its creator’s name and thereby attesting to the incredible success of his manner: Palladianism. Jacob van Campen (1595-1657), home of count Jean-Maurice de Nassau-Siegen, known as Mauritshuis, The Hague (the Netherlands), 1633-1644. Source : Wikimedia Commons. The Origins of Palladianism Born in Padua and long active in Vicenza, two cities dominated by Venice, Pietro della Gondola (1508-1580) had an exceptional career. A mason by formation, he befriended the humanists Giorgio Trissino (1478-1550), who renamed him Palladio, and Daniele Barbaro (1514-70), whom he assisted in the latter’s commented translation of Vitruvius’s treatise on Latin architecture (1556), two encounters that were behind the extraordinary esthetic and conceptual revolution of his art. -

Palladio and Vitruvius: Composition, Style, and Vocabulary of the Quattro Libri

LOUIS CELLAURO Palladio and Vitruvius: composition, style, and vocabulary of the Quattro Libri Abstract After a short preamble on the history of the text of Vitruvius during the Renaissance and Palladio’s encounter with it, this paper assesses the Vitruvian legacy in Palladio’s treatise, in focusing more particularly on its composition, style, and vocabulary and leaving other aspects of his Vitruvianism, such as his architectural theory and the five canonical orders, for consideration in subsequent publications. The discussion on composition concerns Palladio’s probable plans to complete ten books, as an explicit reference to Vitruvius’ treatise. As regards style, the article highlights Palladio’s intention to produce an illustrated treatise like those of Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Sebastiano Serlio, and Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola (whereas the treatise of Vitruvius was probably almost unillustrated), and Palladio’s Vitruvian stress on brevity. Palladio is shown to have preferred vernacular technical terminology to the Vitruvian Greco-Latin vocabulary, except in Book IV of the Quattro Libri in connection with ancient Roman temples. The composition, style, and vocabulary of the Quattro Libri are important issues which contribute to an assessment of the extent of Palladio’s adherence to the Vitruvian prototype in an age of imitation of classical literary models. Introduction The De architectura libri X (Ten Books on Architecture) of the 1st-Century BCE Roman architect and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio was a text used by Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) and many other Renaissance architects both as a guide to ancient architecture and as a source of modern design. Vitruvius is indeed of great significance for Renaissance architecture, as his treatise can be considered as a founding document establishing the ground rules of the discipline for generations after its first reception in the Trecento and early Quattrocento.1 His text offers a comprehensive overview of architectural practice and the education required to pursue it successfully. -

Veneziaterreing.Pdf

ACCESS SCORZÉ NOALE MARCO POLO AIRPORT - Tessera SALZANO S. MARIA DECUMANO QUARTO PORTEGRANDI DI SALA D'ALTINO SPINEA MIRANO MMEESSTTRREE Aeroporto Marco Polo SANTA LUCIA RAILWa AY STATION - Venice MARGHERA ezia TORCELLO Padova-Ven BURANO autostrada S.GIULIANO DOLO MIRA MURANO MALCONTENTA STRÀ i ORIAGO WATER-BUS STATION FIESSO TREPORTI CAVALLINO D'ARTICO FUSINA VTP. - M. 103 for Venice PUNTA SABBIONI RIVIERA DEL BRENTA VENEZIA LIDO WATER-BUS STATION MALAMOCCO VTP - San Basilio ALBERONI z S. PIETRO IN VOLTA WATER-BUS STATION Riva 7 Martiri - Venice PORTOSECCO PELLESTRINA P PIAZZALE ROMA CAe R PARK - Venice P TRONCHETTO CAR PARK - Venice P INDUSTRIAL AREA Cn AR PARK - Marghera P RAILWAY-STATION CAR PARK - Mestre e P FUSINA CAR PARK - Mestre + P SAN GIULIANO CAR PARK - Mestre V P PUNTA SABBIONI CAR PARK - Cavallino The changing face of Venice The architect Frank O. Gehry has been • The Fusina terminal has been designed entrusted with developing what has been by A. Cecchetto.This terminal will be of SAVE, the company that has been run- • defined as a project for the new airport strategic importance as the port of entry ning Venice airport since 1987 is exten- marina. It comprises a series of facilities from the mainland to the lagoon and ding facilities to easily cope with the con- that are vital for the future development historical Venice. stant increase in traffic at Venice airport. of the airport, such as a hotel and an The new airport is able to process 6 mil- The new water-bus station has been desi- administration centre with meeting and • lion passengers a year.