Universi^ Micixsilms International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rudolf Wittkower and Architectural Principles in the Age of Modernism Author(S): Alina A

Rudolf Wittkower and Architectural Principles in the Age of Modernism Author(s): Alina A. Payne Source: The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Sep., 1994), pp. 322-342 Published by: Society of Architectural Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/990940 Accessed: 15/10/2009 16:45 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sah. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society of Architectural Historians is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. http://www.jstor.org Rudolf Wittkower and Architectural Principles in the Age of Modernism ALINA A. -

Essays on British Women Poets B Studi Di Letterature Moderne E Comparate Collana Diretta Da Claudia Corti E Arnaldo Pizzorusso 15

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Florence Research ESSAYS ON BRITISH WOMEN POETS B STUDI DI LETTERATURE MODERNE E COMPARATE COLLANA DIRETTA DA CLAUDIA CORTI E ARNALDO PIZZORUSSO 15 SUSAN PAYNE ESSAYS ON BRITISH WOMEN POETS © Copyright 2006 by Pacini Editore SpA ISBN 88-7781-771-2 Pubblicato con un contributo dai Fondi Dipartimento di Storia delle Arti e dello Spettacolo di Firenze Fotocopie per uso personale del lettore possono essere effettuate nei limiti del 15% di ciascun volume/fascicolo di periodico dietro pagamento alla SIAE del compenso previsto dall’art. 68, comma 4, della legge 22 aprile 1941 n. 633 ovvero dall’accordo stipulato tra SIAE, AIE, SNS e CNA, CONFARTIGIANATO, CASA, CLAAI, CONFCOMMERCIO, CONFESERCENTI il 18 dicembre 2000. Le riproduzioni per uso differente da quello personale potranno avvenire solo a seguito di specifica autorizzazione rilasciata dagli aventi diritto/dall’editore. to Jen B CONTENTS Introduction . pag. 7 Renaissance Women Poets and the Sonnet Tradition in England and Italy: Mary Wroth, Vittoria Colonna and Veronica Franco. » 11 The Poet and the Muse: Isabella Lickbarrow and Lakeland Romantic Poetry . » 35 “Stone Walls do not a Prison Make”: Two Poems by Alfred Tennyson and Emily Brontë . » 59 Elizabeth Barrett Browning: The Search for a Poetic Identity . » 77 “Love or Rhyme”: Wendy Cope and the Lightness of Thoughtfulness . » 99 Bibliography. » 121 Index. » 127 B INTRODUCTION 1. These five essays are the result of a series of coincidences rather than a carefully thought out plan of action, but, as is the case with many apparently haphazard choices, they reflect an ongoing interest which has lasted for the past ten years. -

Debate Association & Debate Speech National ©

© National SpeechDebate & Association DEBATE 101 Everything You Need to Know About Policy Debate: You Learned Here Bill Smelko & Will Smelko DEBATE 101 Everything You Need to Know About Policy Debate: You Learned Here Bill Smelko & Will Smelko © NATIONAL SPEECH & DEBATE ASSOCIATION DEBATE 101: Everything You Need to Know About Policy Debate: You Learned Here Copyright © 2013 by the National Speech & Debate Association All rights reserved. Published by National Speech & Debate Association 125 Watson Street, PO Box 38, Ripon, WI 54971-0038 USA Phone: (920) 748-6206 Fax: (920) 748-9478 [email protected] No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, now known or hereafter invented, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, information storage and retrieval, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. The National Speech & Debate Association does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, age, gender identity, gender expression, affectional or sexual orientation, or disability in any of its policies, programs, and services. Printed and bound in the United States of America Contents Chapter 1: Debate Tournaments . .1 . Chapter 2: The Rudiments of Rhetoric . 5. Chapter 3: The Debate Process . .11 . Chapter 4: Debating, Negative Options and Approaches, or, THE BIG 6 . .13 . Chapter 5: Step By Step, Or, It’s My Turn & What Do I Do Now? . .41 . Chapter 6: Ten Helpful Little Hints . 63. Chapter 7: Public Speaking Made Easy . -

Janson. History of Art. Chapter 16: The

16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 556 16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 557 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER The High Renaissance in Italy, 1495 1520 OOKINGBACKATTHEARTISTSOFTHEFIFTEENTHCENTURY , THE artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote in 1550, Truly great was the advancement conferred on the arts of architecture, painting, and L sculpture by those excellent masters. From Vasari s perspective, the earlier generation had provided the groundwork that enabled sixteenth-century artists to surpass the age of the ancients. Later artists and critics agreed Leonardo, Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giorgione, and with Vasari s judgment that the artists who worked in the decades Titian were all sought after in early sixteenth-century Italy, and just before and after 1500 attained a perfection in their art worthy the two who lived beyond 1520, Michelangelo and Titian, were of admiration and emulation. internationally celebrated during their lifetimes. This fame was For Vasari, the artists of this generation were paragons of their part of a wholesale change in the status of artists that had been profession. Following Vasari, artists and art teachers of subse- occurring gradually during the course of the fifteenth century and quent centuries have used the works of this 25-year period which gained strength with these artists. Despite the qualities of between 1495 and 1520, known as the High Renaissance, as a their births, or the differences in their styles and personalities, benchmark against which to measure their own. Yet the idea of a these artists were given the respect due to intellectuals and High Renaissance presupposes that it follows something humanists. -

Renaissance Sgraffito Facades and the Circulation of Objects in the Mediterranean

ALINA PAYNE Renaissance sgraffito Facades and the Circulation of Objects in the Mediterranean In scholarship on Renaissance architecture ornament has become synonymous with columns and entablatures, friezes and capitals. In effect this is the default setting for any discussion of the topic: in the wake of Leon Battista Alberti the column was ac- knowledged to be »the principal ornament without any doubt«, such that even ap- plied carved panels and sculpture have remained on the periphery of theoretical at- tention at the time, and scholarly thereafter. Vitruvius was the reference point and what was not to be found in his text fell into oblivion no matter how much present in practice. Even fi gural sculpture, attached to so many early modern facades, fell outside of the discussions, as if extraneous to their architectural support.1 In this essay I would like to turn to a different and even more neglected archi- tectural device – the sgraffi to façade – a fl amboyant, extreme instance of pure orna- ment, that has experienced an almost total eclipse in scholarly work, entirely elim- inated from the Western scholar’s Aufgaben (fi g. 1). Indeed scholars’ attention has been almost exclusively turned to the carved stone façade, that is, a tectonic con- struct that combines the ubiquitous orders with sculptural elements into a modu- lated three-dimensional structure. This is the tradition of the Bramante/Raphael/ Peruzzi palace façade, subsequently modifi ed by Michelangelo, and it is the tradi- tion that derives from him that made this formulation into the predominant semi- otic expression of architecture as tectonic/sculptural build-up. -

Guidelines of Modern Management of Historic Ruins : Best Practices

Institutions participating in the elaboration of the publication: Lublin University of Technology (Poland) Matej Bel University (Slovakia) The Institute of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics of The Czech Academy of Sciences (Czech Republic) Polish National Committee of The International Council on Monuments and Sites Icomos (Poland) City of Zadar (Croatia) Links Foundation – Leading Innovation and Knowledge for Society (Italy) Italian Association for The Council of Municipalities and Regions of Europe (Italy) Venetian Cluster (Italy) Municipality of Velenje (Slovenia) Zadar County Development Agency Zadra Nova (Croatia) Team of authors: Bugosław Szmygin (project coordinator) Maciej Trochonowicz Miloš Drdácký Alenka Rednjak Bartosz Szostak Jakub Novotný Marija Brložnik Andrzej Siwek Patrizia Borlizzi Rudi Vuzem Anna Fortuna-Marek Antonino Frenda Marko Vučina Beata Klimek Silvia Soldano Jernej Korelc Katarzyna Drobek Marco Valle Darja Plaznik Ivan Murin Raffaella Lioce Danijela Brišnik Dagmara Majerová Dario Bertocchi Breda Krajnc Jana Jaďuďová Camilla Ferri Urška Todorovska-Šmajdek Iveta Marková Daniele Sferra Milana Klemen Kamila Borseková Sergio Calò Lucija Čakš Orač Anna Vaňová Maurizio Malè Branka Gradišnik Dana Benčiková Eugenio Tamburrino Urška Gaberšek Ivan Souček Patricija Halilović Krasanka Majer Jurišić Martin Miňo Rok Poles Boris Mostarčić Jiří Bláha Marija Ževart Iva Papić Dita Machová Helena Knez Wei Zhang Drago Martinšek Publication within project “RUINS: Sustainable re-use, preservation and modern management of historical ruins in Central Europe - elaboration of integrated model and guidelines based on the synthesis of the best European experiences”, supported by the Interreg CENTRAL EUROPE Programme funded under the European Regional Development Fund. GUIDELINES OF MODERN MANAGEMENT OF HISTORIC RUINS BEST PRACTICES HANDBOOK Guidelines for modern management of historic ruins. -

Artist's Proposal

Gabbert Artist’s Proposal 14th Street Roundabout Page 434 of 1673 Gabbert Sarasota Roundabout 41&14th James Gabbert Sculptor Ladies and Gentlemen, Thank you for this opportunity. For your consideration I propose a work tentatively titled “Flame”. I believe it to be simple-yet- compelling, symbolic, and appropriate to this setting. Dimensions will be 20 feet high by 14.5 feet wide by 14.5 feet deep. It sits on a 3.5 feet high by 9 feet in diameter base. (not accurately dimensioned in the 3D graphics) The composition. The design has substance, and yet, there is practically no impediment to drivers’ visibility. After review of the design by a structural engineer the flame flicks may need to be pierced with openings to meet the 150 mph wind velocity requirement. I see no problem in adjusting the design to accommodate any change like this. Fire can represent our passions, zeal, creativity, and motivation. The “flame” can suggest the light held by the Statue of Liberty, the fire from Prometheus, the spirit of the city, and the hearth-fire of 612.207.8895 | jgsculpture.webs.com | [email protected] 14th Street Roundabout Page 435 of 1673 Gabbert Sarasota Roundabout 41&14th James Gabbert Sculptor home. It would be lit at night with a soft glow from within. A flame creates a sense of place because everyone is drawn to a fire. A flame sheds light and warmth. Reference my “Hopes and Dreams” in my work example to get a sense of what this would look like. The four circles suggest unity and wholeness, or, the circle of life, or, the earth/universe. -

Full Beacher

THE April 13, 2006 THE CENTURY 21 Long Beach Realty TM 1401 Lake Shore Drive ~ 3100 Lake Shore Drive 123 (219) 874-5209 ~ (219) 872-1432 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 T www.c21longbeachrealty.com Open 7 Days a Week 2207 Lake Shore Drive, Long Beach Volume 22, Number 14 Thursday, April 13, 2006 Wetomachek built in 1924 and renamed Mary Hill in 1946, this substantially built Dutch Colonial enjoys the charm and grace of yester- year. On 80 feet of hillside Lake Shore Drive property, views over Lake Michigan reach from Illinois to Michigan. Huge living room with wood burning fireplace opens to 640 feet of wrap around glass enclosed porch with handsome pillars and charming Hoosier fireplace. Redwood walls and ceilings in huge dining room. Family sized kitchen. Eight rooms include over 2700 square feet of living area. Wood floors, redwood paneling, drywall over plaster walls. Ceramic baths. Double garage. Charming playhouse and extra parking is off of Round About Easter NEW LISTING one way street at rear. For the buyer who appreciates charm and quality; here is Round about Eastertime, Round about Easter perfection. $1,300,000 Quick as a wink, You’ll thrill to the stir Ribbon grass freshens Of catkins wakening, And flowers turn pink. Starting to purr. Eggs in their baskets Robins returning Take on overnight Will carol new cheer, Strangest of colors Bluebells start ringing – Artistically bright. Glad Easter is here. Bunnies go hippity – Hopping about, 4967 Remington Square, LaPorte 409 Coolspring Avenue, Michigan City Trees in the woodlands 1 Energy Star Rated spacious 4 bedroom, 2 ⁄2 bath home on Bright, Spacious, and Inviting two story just a short walk from a corner lot in Hunters Run subdivision. -

Lago Di Garda • Lake Garda • Gardasee

GARD MORE LAGO DI GARDA • LAKE GARDA • GARDASEE SALÒ LAZISE EVENTS ITINERARIES OF GARDA ISSN 2499-7730 ANNO 4 • N. 7 | PRIMAVERA 2019 | € 3,50 CIERRE GRAFICA “L’UNIONE FA LA FORZA” nei tempi moderni. OUR SERVICES - promozione d el territorio in - d epliant web - loc and ine - menu - app native - c artelline - - le a 360° info@ga rda -ma rketing.com LAKEGARDA Lago di Garda - Lake Garda www.pilandro.com PILANDRO WINE SHOP Degustazioni - Wine tasting - Wein proben Orari di apertura / Opening Hours / Öffnungszeiten Lunedì-Sabato / Monday-Saturday / Montag-Samstag 8.30-12.30/14.00-18.00 Domenica / Sunday / Sonntag 8.30-12.30 Località Pilandro, 1 - Desenzano del Garda (BS) (Uscita/Exit/Ausfahrt: A4 Sirmione) GPS: N 45° 44’ 10” E 10° 61’ 17” T. +39 030 991 0363 www.pilandro.com - [email protected] - [email protected] GARD MORE ADVERTISERS THANKS TO ANNO 4 • N. 7 | PRIMAVERA 2019 YEAR 4 • No. 7 | SPRING 2019 JAHRGANG 4 • Nr. 7 | FRÜHLING 2019 II Web, Print and Ideas Garda Marketing Semestrale di Territorio, Turismo, Cultura Registro Stampa n. 2073, Tribunale di Verona Wine tasting Direttore Responsabile Claudia Farina - 347 42 82 583 1 [email protected] Pilandro Redazione Alvaro Ioppi - 349 23 26 094 Collaboratori Shopping Francesca Gardenato, Stefano Ioppi, Elisa Turcato 6-7 Elnòs Shopping Progetto grafco e impaginazione Marco Castagna Traduzioni logoService - Brescia Stampa Cierre Grafca Fashion & Design Via Ciro Ferrari 5, Caselle di Sommacampagna (VR) 28-29 tel. 045 8580900 - www.cierrenet.it Pelletteria Charlotte Distributore per Verona e Lago di Garda Ag. Sidetra s.r.l. -

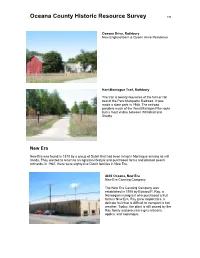

West Michigan Pike Route but Is Most Visible Between Whitehall and Shelby

Oceana County Historic Resource Survey 198 Oceana Drive, Rothbury New England Barn & Queen Anne Residence Hart-Montague Trail, Rothbury The trail is twenty-two miles of the former rail bed of the Pere Marquette Railroad. It was made a state park in 1988. The railroad parallels much of the West Michigan Pike route but is most visible between Whitehall and Shelby. New Era New Era was found in 1878 by a group of Dutch that had been living in Montague serving as mill hands. They wanted to return to an agrarian lifestyle and purchased farms and planted peach orchards. In 1947, there were eighty-five Dutch families in New Era. 4856 Oceana, New Era New Era Canning Company The New Era Canning Company was established in 1910 by Edward P. Ray, a Norwegian immigrant who purchased a fruit farm in New Era. Ray grew raspberries, a delicate fruit that is difficult to transport in hot weather. Today, the plant is still owned by the Ray family and processes green beans, apples, and asparagus. Oceana County Historic Resource Survey 199 4775 First Street, New Era New Era Reformed Church 4736 First Street, New Era Veltman Hardware Store Concrete Block Buildings. New Era is characterized by a number of vernacular concrete block buildings. Prior to 1900, concrete was not a common building material for residential or commercial structures. Experimentation, testing and the development of standards for cement and additives in the late 19th century, led to the use of concrete a strong reliable building material after the turn of the century. Concrete was also considered to be fireproof, an important consideration as many communities suffered devastating fires that burned blocks of their wooden buildings Oceana County Historic Resource Survey 200 in the late nineteenth century. -

Ms Coll\Wittkower Wittkower, Rudolf. Papers, [Ca. 1923J-1978. 19.5

Ms Coll\Wittkower Wittkower, Rudolf. Papers, [ca. 1923J-1978. 19.5 linear ft. (ca. 23,200 items in 45 boxes, 8 card files) Biography: Rudolf Wittkower (1901-1971) was professor of art history at Columbia University, 1956-1969. Summary: Working files of Wittkower, dealing with Baroque and Renaissance painting, sculpture, and architecture. Included are manuscripts, notes, drawings, annotated proofs of articles and books, and some correspondence related to his writings and lectures. The majority of the files document his teaching, research, and writing at the University of London, 1934-1955, and at Columbia University. There also are some manuscript notes from his early years in Italy and Germany. Series I has been divided into six parts: Artists, Subjects, Book Manuscripts, Proofs, Notes, and Printed Materials. Some of the major files are Bernini, Bramante, Carracci, Michelangelo, and Raphael (Artists); Baroque Painting, Patronage, Rome, St. Peter's, Slade Lectures on the history of art (Subjects); Art and Architecture in Italy, Born under Saturn, and Matthews Lectures: Gothic vs. Classic (Book Manuscripts). In addition there are proofs of essays and reviews with manuscript corrections and emendations, copies of several of his own published works with his manuscript corrections, and typescript insertions for new editions. The Notes consist of eight card file boxes with notes chiefly relating to the Baroque period and Bernini. In Series I the contents of the parts overlap. For example, material relating to Bernini can be found in Artists, in Subjects under Rome and St. Peter's, and in Notes. Series II consists of manuscripts, typescripts, notes, galleys, and corrected page proofs of Wittkower's lectures and articles on Renaissance and Baroque sculpture and architecture, which were edited posthumously by Margot Wittkower for inclusion in Sculpture: Process and Principle (1977) and The Collected Essays of Rudolf Wittkower (1978). -

Taking Shape Before Our Eyes - WSJ

6/16/2019 Taking Shape Before Our Eyes - WSJ BREAKING NEWS Gary Woodland wins the U.S. Open, capturing his irst major title after holding o a charge by two-time defending champion Brooks Koep This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. To order presentationready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers visit https://www.djreprints.com. https://www.wsj.com/articles/takingshapebeforeoureyes11560528609 MASTERPIECE Taking Shape Before Our Eyes With its energetic lines, full figures and thrilling sense of tactility, Raphael’s cartoon for his fresco ‘School of Athens’ is a breathtaking artwork in its own right. ‘School of Athens’ (1510), by Raphael PHOTO: VENERANDA BIBLIOTECA AMBROSIANA, MONDADORI PORTFOLIO By Cammy Brothers June 14, 2019 1210 p.m. ET The fame of Raphael’s “School of Athens,” painted between 1508 and 1510 for the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican, makes it almost impossible to actually see. One must endure the lines, the crush of humanity in the room itself and rushing by to get to the Sistine Chapel. Beyond this, like any work of art known through countless reproductions, it is difficult to approach with fresh eyes. What an extraordinary satisfaction, then, in the galleries of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, to see it in peace, albeit in another form. Since March, Raphael’s preliminary drawing, or cartoon, measuring over 25 feet across, has been on display in a newly designed room after a four-year restoration. Unlike the other large-scale surviving cartoons by Raphael at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, it can be seen up close, at eye level and behind nonreflective glass.