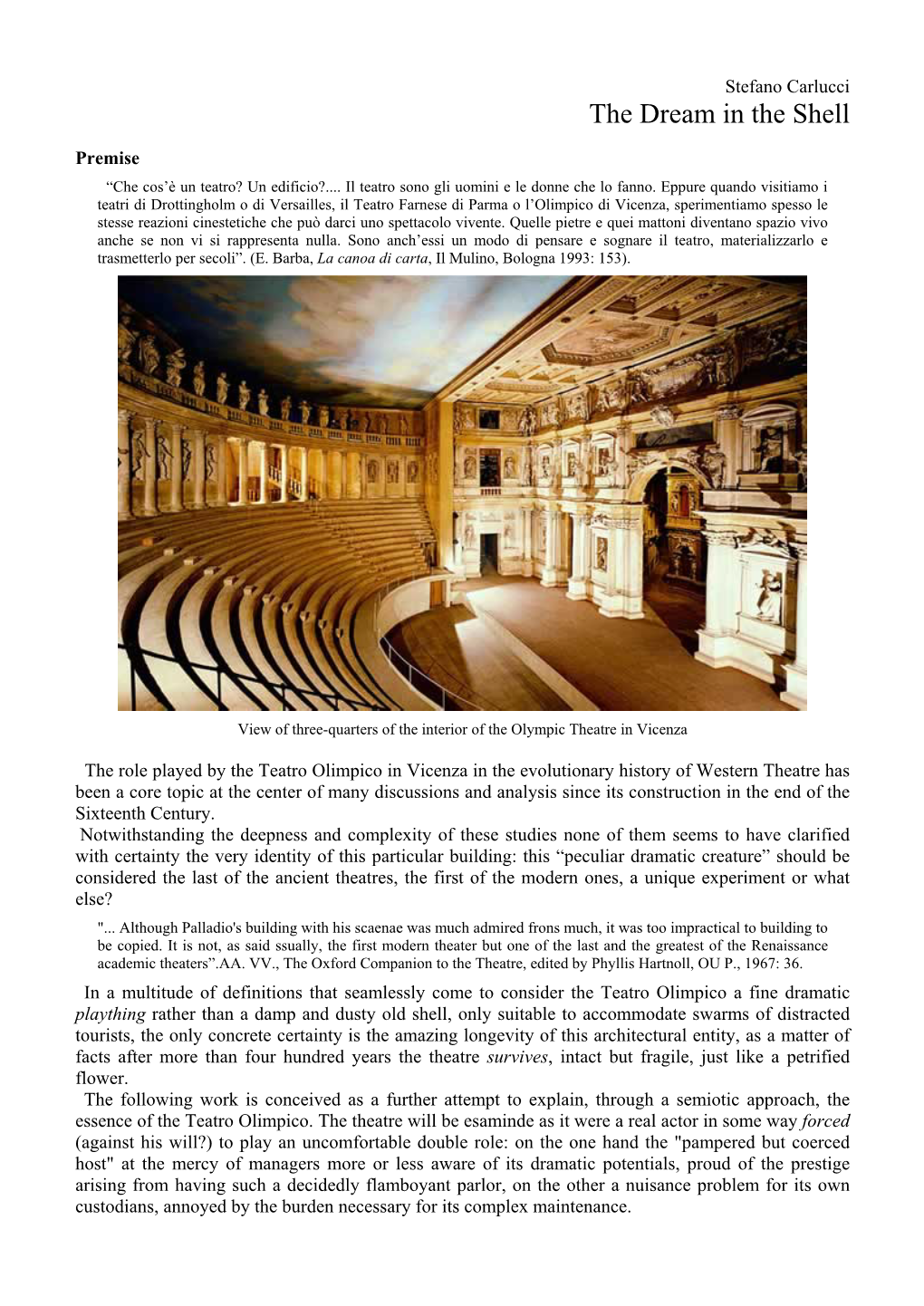

The Dream in the Shell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mantua SIMPLY WONDERFUL Piazza Sordello

MANTUA SIMPLY WONDERFUL Piazza Sordello MANTUA. SIMPLY WONDERFUL Those who arrive in Mantua are captivated by its unique, timeless allure and welcoming atmosphere. A city which enjoys a breathtaking panorama when viewed from the shores of its lakes. It appears as though it is suspended above the water, a protagonist of an almost surreal landscape, composed of a balance of history, art and nature. Mantua is a city to be visited with ample time, consideration and serenity. The city squares, passageways and cobblestone streets invite the visitor to slowly take in every one of its monuments and historic buildings in order to understand just why it has been declared by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site along with the neighboringneighbouring town of Sabbioneta. Mantua weaves history, art and culture together everywhere and it is surrounded by an unparalleled natural atmosphere. Unique and magical places that make Mantua simply wonderful. 2 View of the city Mantua at sunset 3 Sabbioneta MANTUA AND SABBIONETA: WORLD HERITAGE SITE July of 2008 is the month when Mantua and neighbouring Sabbioneta where introduced to the list of World Heritage Sites as a unique point of importance. Both cities enjoyed moments of great design importance during the renaissance. Designed and created by the same ruling family, the Gonzaga, two different but complimentary models were applied for each location. In fact, Sabbioneta is a newer city realized by Vespasiano Gonzaga in the second half of the sixteenth century as the ideal capital for his duchy; Mantua instead presents itself as a transformation of an existing city, which changed the ancient urban configuration. -

Shakespeare in Italy Richard Paul

8. From The Shakespeare Guide to Italy, by Richard Paul Roe 2011 ______________________________________________________________________________ Richard Paul Roe, who died soon after publishing The Shakespeare Guide to Italy,1 exemplifies the best of the Oxfordian mind. A retired attorney and Shakespeare enthusiast, Roe meticulously followed up every possible reference to Italy in the Works, and over 20 years visited each one. His discoveries show that “the playwright,” as Roe tactfully calls him, knew Italy at first hand and in detail. This single fact alone calls the traditional authorship account into question, since the Stratford grain dealer never left England. The earl of Oxford, on the other hand, extensively visited Italy, including all the towns, cities and regions featured in the plays and poems. The following extract from Chapter 8, “Midsummer in Sabbioneta” describes Roe’s exciting discovery of renaissance Italy’s “little Athens,” the true location of A Midsummer Night’s Dream Richard Paul Roe 1922-2010 . Roe’s book is illustrated with his and Stephanie Hopkins Hughes’s eloquent photographs captioned with witty and often illuminating comments. ______________________________________________________________________________ n my way from Verona to Florence, I made a stop-over for a few days in Mantua, to see the many great works of Giulio Romano (c. 1499-1546). 1t was a kind of pilgrimage: O Giulio Romano is the only Renaissance artist ever named by the playwright. His name is spoken by the Third Gentleman in The Winter’s Tale, V.ii: No: the princess hearing of her mother’s Statue, which is in the keeping of Paulina— A piece many years in doing and now newly Performed by that rare Italian master, Julio Romano, who, had he himself eternity and Could put breath into his work, would beguile Nature of her custom, so perfectly he is her ape … On a Sunday morning, a few days later, when ready to continue e on to Florence, I was chatting at breakfast with another traveler. -

Lex Hermans, Dynastic Pride in the Farnese Theatre at Parma (Summary)

Lex Hermans Dynastic Pride in the Farnese Theatre at Parma From 1615 onwards Duke Ranuccio I of Parma and Piacenza (1569–1622) sought to arrange a marriage between his son Odoardo (born 1612) and a Medici princess. When in 1617 it was announced that Cosimo II of Tuscany would travel to Milan, Ranuccio saw this as an opportunity to entertain the grand duke on his progress. He had built a huge theatre in his palace at Parma, with capacity to seat some 1,500 guests, which was arranged according to ideas about courtly theatres that were developed over the sixteenth century. It is an impressive architectonic construction, richly decorated with meaningful paintings and statues, and designed for broadcasting its patron’s status and magnificence to foreign guests and local notables. In this essay, the structure and the decoration of the Teatro Farnese are considered as a ‘distributed portrait’; the theatre was a visual portfolio of Ranuccio’s various qualities. The statues of personified virtues, evenly divided between followers of the goddess of war and of the Muses, the deities to which the duke dedicated the theatre, testified to his balanced rule and fair way of acting, to his magnanimity, and to his pursuit of the arts. The form of the theatre itself also shows this double connection: it can be used as an arena for indoor jousting and military ‘ballets’, and it contains a stage where to perform musical and theatrical shows. The architectural shell, with its palace-like stage set and its two tiers of Serlian arches would remind visitors of the renaissance tradition that identified theatres as the original places of government assemblies. -

Italian Piazze: Models for Public Outdoor Space in Sustainable Communities

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship 2013 Italian piazze: models for public outdoor space in sustainable communities Mark K. (Mark Kevan) Pederson Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Pederson, Mark K. (Mark Kevan), "Italian piazze: models for public outdoor space in sustainable communities" (2013). WWU Graduate School Collection. 266. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/266 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ................................................................................................................................................ Italian Piazze: Models for Public Outdoor Space in Sustainable Communities By Mark K. Pederson Accepted in Partial Completion Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science ________________________ Kathleen L. Kitto, Dean of the Graduate School ADVISORY COMMITTEE ________________________ Chair, Dr. Nicholas C. Zaferatos ________________________ Dr. Gigi Berardi ________________________ Dr. Paul A. Stangl .............................................................................................................................................. -

Verona Featuring Venice and the Italian Lakes

SMALL GROUP Ma xi mum of LAND 24 Travele rs JO URNEY Verona featuring Venice and the Italian Lakes Inspiring Moments > Embrace the romantic ambience of Verona, where Romeo and Juliet fell in love, brimming with pretty piazzas, quiet parks and a Roman arena. > Wander through the warren of narrow INCLUDED FEATURES streets and bridges that cross the canals of Venice. Accommodations (with baggage handling) Itinerary > Dine on classic cuisine and sip the – 7 nights in Verona, Italy, at the Day 1 Depart gateway city Veneto’s renowned wines as you first-class Hotel Indigo Verona – Day 2 Arrive in Verona and transfer enjoy a homemade meal. Grand Hotel des Arts. to hotel. > Cruise Lake Garda and experience the Extensive Meal Program Day 3 Verona chic Italian lakes lifestyle. – 7 breakfasts, 3 lunches and 3 dinners, Day 4 Lake Garda | Valpolicella Winery > Admire Palladio’s architectural including Welcome and Farewell Dinners; Day 5 Venice genius in Vicenza . tea or coffee with all meals, plus wine Day 6 Verona > Experience three UNESCO World with dinner. Day 7 Bassano del Grappa | Vicenza Heritage sites. – Opportunities to sample authentic cuisine and local flavors Day 8 Padua | Verona Day 9 Transfer to airport and depart Scenic Lago di Garda Your One-of-a-Kind Journey for gateway city – Discovery excursions highlight the local culture, heritage and history. Flights and transfers included for AHI FlexAir participants. – Expert-led Enrichment programs Note: Itinerary may change due to local conditions. enhance your insight into the region. Activity Level: We have rated all of our excursions with activity levels to help you assess this program’s physical – AHI Sustainability Promise: expectations. -

Libraries: Architecture and the Ordering of Knowledge

Libraries: Architecture and the Ordering of Knowledge English text of March 29, 2009, by J. Connors for “Biblioteche: l’architettura e l’ordinamento del sapere,” with Angela Dressen, in Il Rinascimento Italiano e l’Europa, vol. 6, Luoghi, spazi, architetture, ed. Donatella Calabi and Elena Svalduz, Treviso-Costabissara, 2010, pp. 199-228. All the texts describing ancient libraries had been rediscovered by the mid-Quattrocento. Humanists knew Greek and Roman libraries from the accounts in Strabo, Varro, Seneca, and especially Suetonius, himself a former prefect of the imperial libraries. From Pliny everyone knew that Asinius Pollio founded the first public library in Rome, fulfilling the unrealized wish of Juliuys Caesar ("Ingenia hominum rem publicam fecit," "He made men's talents public property"). From Suetonius it was known that Augustus founded two libraries, one in the Porticus Octaviae, and another, for Greek and Latin books, in the temple of Apollo on the Palatine, where the sculptural decoration included not only a colossal statue of Apollo but also portraits of celebrated writers. The texts spoke frequently of author portraits, and also of the wealth and splendor of ancient libraries. The presses for the papyrus rolls were made of ebony and cedar; the architectural order and the revetments of the rooms were of marble; the sculpture was of gilt bronze. Boethius added that libraries were adorned with ivory and glass, while Isidore mentioned gilt ceilings and restful green cipollino floors. Senecan disapproval of ostentatious libraries, of "studiosa luxuria," of piling up more books than one could ever read, gave way to admiration for magnificent libraries. -

Vincenzo Scamozzi

Vincenzo Scamozzi Nato: nel 1552 a Vicenza - Morto: 7 agosto 1616 a Venezia Formazione: dopo una prima educazione ricevuta a Vicenza dal padre Giandomenico, imprenditore edile benestante di origini valtellinesi culturalmente legato a Sebastiano Serlio, nel 1572 si stabilì a Venezia, dove studiò il trattato di Vitruvio nell’interpretazione di Daniele Barbaro e di Andrea Palladio, deducendone un linguaggio architettonico del tutto personale che si valeva di principi metodologici basati su ragione e scienza. Sui suoi principi architettonici egli scrisse un trattato, Dell’idea di architettura universale, (Venezia1591-1615). Nel 1578 soggiornò per la prima volta a Roma,dedicandosi allo studio e al rilievo dei monumenti antichi. Tornato a Vicenza, in collaborazione con il padre realizzò una serie di palazzi e ville nella città natale e nella provincia, lavorando inoltre al completamento di alcune opere di Palladio. Progettò a Vicenza il Palazzo Godi (1569), molto alterato nell’esecuzione postuma, Villa Verlato a Villa verla (VI) (1574), costruì a Lonigo (VI) la Villa detta Rocca Pisana (1576) e a Vicenza Palazzo Trissino (1577-79). Ripresa l’attività a Venezia, costruì, continuando la libreria di S. Marco, iniziata da Sansovino, le Procuratie Nuove (1582-85 fino alla decima arcata) e, dopo la morte di Palladio, condusse a compimento a Vicenza il Teatro Olimpico, di cui realizzò anche l’apparato scenico seguendo i principi di Sebastiano Serlio e che ebbe un seguito nella progettazione del teatro di Sabbioneta (1588-1590). Dello stesso periodo sono due progetti per il Ponte di Rialto a Venezia (1588), mentre intorno al 1606 fornì i disegni per il duomo e il palazzo arcivescovile di Salisburgo. -

OGGETTO: Venezia – Ex Palazzo Reale

MINISTERO PER I BENI E LE ATTIVITA’ CULTURALI DIREZIONE REGIONALE PER I BENI CULTURALI E PAESAGGISTICI DEL VENETO Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici e Paesaggistici di Venezia e Laguna Palazzo Ducale, 1 V e n e z i a PERIZIA DI SPESA N. 23 del 2 luglio 2012 D.P.C.M. 10 Dicembre 2010 di ripartizione della quota dell’otto per mille dell’IRPEF a diretta gestione statale per l’anno 2010 RELAZIONE STORICA E RELAZIONE TECNICA CON CRONOPROGRAMMA VENEZIA – PIAZZA SAN MARCO LAVORI DI CONSERVAZIONE DELLA FACCIATA, DEL PORTICO E DELLE COPERTURE DELLE PROCURATIE NUOVE – Campate XI – XXXVI C.U.I. 13854 CUP F79G10000330001 Venezia, 2 LUGLIO 2012 IL PROGETTISTA Visto:IL SOPRINTENDENTE Arch. Ilaria Cavaggioni arch. Renata Codello IL RESPONSABILE DEL PROCEDIMENTO Arch. Anna Chiarelli Venezia - Procuratie Nuove o Palazzo Reale Intervento di conservazione della facciata principale e dalla falda di copertura (…) guardatevi dal voler comparire sopra le cose fatte: accomodatele, assicuratele, ma non aggiungete, non mutilate, e non fate il bravo. Giuseppe Valdier L’Architettura Pratica, III, p. 115 Relazione illustrativa con cenni sulla storia della fabbrica SOMMARIO 1. Introduzione 2. Cenni sulla storia della fabbrica 3. Caratteri stilistici 4. Caratteri costruttivi 5. La ricerca d’archivio 6. Stato di conservazione 7. Descrizione dell’intervento: linee guida e tecniche 8. Riferimenti bibliografici 1. Introduzione Molti degli aspetti descritti in questa relazione, relativi alla vicenda storica della fabbrica delle Procuratie Nuove, alle caratteristiche stilistiche e costruttive della facciata principale del palazzo, al suo stato di conservazione, ecc., si basano su ipotesi fondate sull’osservazione a distanza, ai piedi della fabbrica, sulla letteratura artistica consultata, su precedenti restauri documentati, su analogie con le Progetto definitivo 2 Venezia - Procuratie Nuove o Palazzo Reale Intervento di conservazione della facciata principale e dalla falda di copertura fabbriche coeve, sulle raccomandazioni dei manuali storici, ecc. -

Teatro Olimpico by Andrea Palladio

Aalborg Universitet Teatro Olimpico by Andrea Palladio an iconic stage scenario; and the diffused lightning system by Mariano Fortuny - enhancing the aura of mystery in the Wagnerian universe Fisker, Anna Marie Published in: eaw2017 SYNCHRESIS – Audio Vision Tales conference Creative Commons License Unspecified Publication date: 2017 Document Version Early version, also known as pre-print Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Fisker, A. M. (2017). Teatro Olimpico by Andrea Palladio: an iconic stage scenario; and the diffused lightning system by Mariano Fortuny - enhancing the aura of mystery in the Wagnerian universe . In eaw2017 SYNCHRESIS – Audio Vision Tales conference (pp. 15). eaw2017 SYNCHRESIS . General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Teatro Olimpico by Andrea Palladio - an iconic stage scenario; and the diffused lightning system by Mariano Fortuny - enhancing the aura of mystery in the Wagnerian universe Abstract My paper deals with the origins of stage design experienced through architecture – pointing out that the term scenography includes all of the elements that contribute to establishing an atmosphere and mood for a theatrical presentation: lighting, sound, set and costume design. -

Discover Padua and Its Surroundings

2647_05_C415_PADOVA_GB 17-05-2006 10:36 Pagina A Realized with the contribution of www.turismopadova.it PADOVA (PADUA) Cittadella Stazione FS / Railway Station Porta Bassanese Tel. +39 049 8752077 - Fax +39 049 8755008 Tel. +39 049 9404485 - Fax +39 049 5972754 Galleria Pedrocchi Este Tel. +39 049 8767927 - Fax +39 049 8363316 Via G. Negri, 9 Piazza del Santo Tel. +39 0429 600462 - Fax +39 0429 611105 Tel. +39 049 8753087 (April-October) Monselice Via del Santuario, 2 Abano Terme Tel. +39 0429 783026 - Fax +39 0429 783026 Via P. d'Abano, 18 Tel. +39 049 8669055 - Fax +39 049 8669053 Montagnana Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 Castel S. Zeno Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 Tel. +39 0429 81320 - Fax +39 0429 81320 (sundays opening only during high season) Teolo Montegrotto Terme c/o Palazzetto dei Vicari Viale Stazione, 60 Tel. +39 049 9925680 - Fax +39 049 9900264 Tel. +39 049 8928311 - Fax +39 049 795276 Seasonal opening Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 nd TREVISO 2 Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 AIRPORT (sundays opening only during high season) MOTORWAY EXITS Battaglia Terme TOWNS Via Maggiore, 2 EUGANEAN HILLS Tel. +39 049 526909 - Fax +39 049 9101328 VENEZIA Seasonal opening AIRPORT DIRECTION TRIESTE MOTORWAY A4 Travelling to Padua: DIRECTION MILANO VERONA MOTORWAY A4 AIRPORT By Air: Venice, Marco Polo Airport (approx. 60 km. away) By Rail: Padua Train Station By Road: Motorway A13 Padua-Bologna: exit Padua Sud-Terme Euganee. Motorway A4 Venice-Milano: exit Padua Ovest, Padua Est MOTORWAY A13 DIRECTION BOLOGNA adova. -

Summary for Gianfrancesco Gonzaga Di Rodigo, 1445-1496, Lord Of

KRESS COLLECTION DIGITAL ARCHIVE Antico, c. 1460-1528 Gianfrancesco Gonzaga di Rodigo, 1445-1496, Lord of Bozzolo, Sabbioneta, and Viadana 1478 [obverse]; Fortune, Mars and Minerva [reverse] IDENTIFIER 895 ARTIST NATIONALITY Antico, c. 1460-1528 Italian MEDIUM bronze TYPE OF OBJECT Sculpture DIMENSIONS diameter: 4.06 cm (1 5/8 in) LOCATION National Gallery of Art, Washington, District of Columbia PROVENANCE Gustave Dreyfus [1837-1914], Paris; his heirs; purchased with the entire Dreyfus collection 9 July 1930 by (Duveen Brothers, Inc., London, New York, and Paris); sold 31 January 1944 to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, New York; [1] gift 1957 to NGA. [1] The Duveen Brothers Records document the firm’s sixteen year pursuit and eventual acquisition of the Dreyfus collection, which included paintings, sculptures, small bronzes, medals, and plaquettes. Bequeathed as part of his estate to Dreyfus’ widow and five children (a son and four daughters), who had differing opinions about its disposition, the collection was not sold until after his widow’s death in April 1929. Duveen did not wish to separate Dreyfus’ collection of small bronzes, medals, and plaquettes, and it was sold intact to the Kress Foundation for a price that was met by installment payments every three months. (Duveen Brothers Records, accession number 960015, Research Library, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles: reel 301, box 446, folders 3 and 4; reel 302, box 447, folders 1-6; reel 303, box 448, folders 1 and 2; reel 330, box 475, folder 4.) See also George Francis Hill’s discussion "A Note on Pedigrees" in his catalogue, The Gustave Dreyfus Collection: Renaissance Medals, Oxford, 1931: xii, which was commissioned by Duveen Brothers. -

Anna Irene Del Monaco

The Shri Radha-Radhanath Temple of Understanding in the formerly Indian township of Chatsworth, Durban. Photo: Anna Irene Del Monaco. 120 Theaters and cities. Flânerie between global north-south metropolis on the traces of migrant architectural models ANNA IRENE DEL MONACO, FRANCESCO MENEGATTI Sapienza Università di Roma; Politecnico di Milano [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract: Theaters around the world are linked by architectural features besides programs and music. (AIDM: A.I. Del Monaco; FM: Francesco Menegatti) The conversation begins by commenting on the concert by Martha Argerich and Daniel Baremboim with the Orchestra Filarmonica della Scala held in Piazza Duomo on May 12, 2016 in Milan. The Concerto in Sol by Ravel is scheduled in the program. The hybrid Neoclassicism of theaters in the modern city between the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries: the Teatro alla Scala in Milan - the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires - the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow - the Sans Souci Theater in Kolkata - the Teatro Massimo in Palermo. AIDM: The Argerich-Baremboim concert and the La Scala Philharmonic Orchestra set up in Piazza Duomo en plein air with 40,000 spectators seems to have been a great success. The two ultra-seventies artists, born in Argentina, seemed at their ease ... two classical music stars within the scenography of Milan urban scenes ... the Cathedral on the right of the stage and the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele in front of the orchestra. This shows how the urban architecture of Italian historical cities, even when it is composed of architectures from different eras, is able to represent a perfect stage, both formal and informal, and the music is always done on the street, en plein air, as we learn, among other things, from the quintet of Luigi Boccherini of 1780 Night music on the streets of Madrid.