Vincenzo Scamozzi Comments on the Architectural Treatise of Sebastiano Serlio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roman Entertainment

Roman Entertainment The Emergence of Permanent Entertainment Buildings and its use as Propaganda David van Alten (3374912) [email protected] Bachelor thesis (Research seminar III ‘Urbs Roma’) 13-04-2012 Supervisor: Dr. S.L.M. Stevens Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 1: The development of permanent entertainment buildings in Rome ...................................... 9 1.1 Ludi circenses and the circus ............................................................................................ 9 1.2 Ludi scaenici and the theatre ......................................................................................... 11 1.3 Munus gladiatorum and the amphitheatre ................................................................... 16 1.4 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 19 2: The uncompleted permanent theatres in Rome during the second century BC ................. 22 2.0 Context ........................................................................................................................... 22 2.1 First attempts in the second century BC ........................................................................ 22 2.2 Resistance to permanent theatres ................................................................................ 24 2.3 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... -

Libraries: Architecture and the Ordering of Knowledge

Libraries: Architecture and the Ordering of Knowledge English text of March 29, 2009, by J. Connors for “Biblioteche: l’architettura e l’ordinamento del sapere,” with Angela Dressen, in Il Rinascimento Italiano e l’Europa, vol. 6, Luoghi, spazi, architetture, ed. Donatella Calabi and Elena Svalduz, Treviso-Costabissara, 2010, pp. 199-228. All the texts describing ancient libraries had been rediscovered by the mid-Quattrocento. Humanists knew Greek and Roman libraries from the accounts in Strabo, Varro, Seneca, and especially Suetonius, himself a former prefect of the imperial libraries. From Pliny everyone knew that Asinius Pollio founded the first public library in Rome, fulfilling the unrealized wish of Juliuys Caesar ("Ingenia hominum rem publicam fecit," "He made men's talents public property"). From Suetonius it was known that Augustus founded two libraries, one in the Porticus Octaviae, and another, for Greek and Latin books, in the temple of Apollo on the Palatine, where the sculptural decoration included not only a colossal statue of Apollo but also portraits of celebrated writers. The texts spoke frequently of author portraits, and also of the wealth and splendor of ancient libraries. The presses for the papyrus rolls were made of ebony and cedar; the architectural order and the revetments of the rooms were of marble; the sculpture was of gilt bronze. Boethius added that libraries were adorned with ivory and glass, while Isidore mentioned gilt ceilings and restful green cipollino floors. Senecan disapproval of ostentatious libraries, of "studiosa luxuria," of piling up more books than one could ever read, gave way to admiration for magnificent libraries. -

Vincenzo Scamozzi

Vincenzo Scamozzi Nato: nel 1552 a Vicenza - Morto: 7 agosto 1616 a Venezia Formazione: dopo una prima educazione ricevuta a Vicenza dal padre Giandomenico, imprenditore edile benestante di origini valtellinesi culturalmente legato a Sebastiano Serlio, nel 1572 si stabilì a Venezia, dove studiò il trattato di Vitruvio nell’interpretazione di Daniele Barbaro e di Andrea Palladio, deducendone un linguaggio architettonico del tutto personale che si valeva di principi metodologici basati su ragione e scienza. Sui suoi principi architettonici egli scrisse un trattato, Dell’idea di architettura universale, (Venezia1591-1615). Nel 1578 soggiornò per la prima volta a Roma,dedicandosi allo studio e al rilievo dei monumenti antichi. Tornato a Vicenza, in collaborazione con il padre realizzò una serie di palazzi e ville nella città natale e nella provincia, lavorando inoltre al completamento di alcune opere di Palladio. Progettò a Vicenza il Palazzo Godi (1569), molto alterato nell’esecuzione postuma, Villa Verlato a Villa verla (VI) (1574), costruì a Lonigo (VI) la Villa detta Rocca Pisana (1576) e a Vicenza Palazzo Trissino (1577-79). Ripresa l’attività a Venezia, costruì, continuando la libreria di S. Marco, iniziata da Sansovino, le Procuratie Nuove (1582-85 fino alla decima arcata) e, dopo la morte di Palladio, condusse a compimento a Vicenza il Teatro Olimpico, di cui realizzò anche l’apparato scenico seguendo i principi di Sebastiano Serlio e che ebbe un seguito nella progettazione del teatro di Sabbioneta (1588-1590). Dello stesso periodo sono due progetti per il Ponte di Rialto a Venezia (1588), mentre intorno al 1606 fornì i disegni per il duomo e il palazzo arcivescovile di Salisburgo. -

OGGETTO: Venezia – Ex Palazzo Reale

MINISTERO PER I BENI E LE ATTIVITA’ CULTURALI DIREZIONE REGIONALE PER I BENI CULTURALI E PAESAGGISTICI DEL VENETO Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici e Paesaggistici di Venezia e Laguna Palazzo Ducale, 1 V e n e z i a PERIZIA DI SPESA N. 23 del 2 luglio 2012 D.P.C.M. 10 Dicembre 2010 di ripartizione della quota dell’otto per mille dell’IRPEF a diretta gestione statale per l’anno 2010 RELAZIONE STORICA E RELAZIONE TECNICA CON CRONOPROGRAMMA VENEZIA – PIAZZA SAN MARCO LAVORI DI CONSERVAZIONE DELLA FACCIATA, DEL PORTICO E DELLE COPERTURE DELLE PROCURATIE NUOVE – Campate XI – XXXVI C.U.I. 13854 CUP F79G10000330001 Venezia, 2 LUGLIO 2012 IL PROGETTISTA Visto:IL SOPRINTENDENTE Arch. Ilaria Cavaggioni arch. Renata Codello IL RESPONSABILE DEL PROCEDIMENTO Arch. Anna Chiarelli Venezia - Procuratie Nuove o Palazzo Reale Intervento di conservazione della facciata principale e dalla falda di copertura (…) guardatevi dal voler comparire sopra le cose fatte: accomodatele, assicuratele, ma non aggiungete, non mutilate, e non fate il bravo. Giuseppe Valdier L’Architettura Pratica, III, p. 115 Relazione illustrativa con cenni sulla storia della fabbrica SOMMARIO 1. Introduzione 2. Cenni sulla storia della fabbrica 3. Caratteri stilistici 4. Caratteri costruttivi 5. La ricerca d’archivio 6. Stato di conservazione 7. Descrizione dell’intervento: linee guida e tecniche 8. Riferimenti bibliografici 1. Introduzione Molti degli aspetti descritti in questa relazione, relativi alla vicenda storica della fabbrica delle Procuratie Nuove, alle caratteristiche stilistiche e costruttive della facciata principale del palazzo, al suo stato di conservazione, ecc., si basano su ipotesi fondate sull’osservazione a distanza, ai piedi della fabbrica, sulla letteratura artistica consultata, su precedenti restauri documentati, su analogie con le Progetto definitivo 2 Venezia - Procuratie Nuove o Palazzo Reale Intervento di conservazione della facciata principale e dalla falda di copertura fabbriche coeve, sulle raccomandazioni dei manuali storici, ecc. -

Mannerism COMMONWEALTH of AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969

ABPL 702835 Post-Renaissance Architecture Mannerism COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Melbourne pursuant to Part VB of the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. do not remove this notice perfection & reaction Tempietto di S Pietro in Montorio, Rome, by Donato Bramante, 1502-6 Brian Lewis Canonica of S Ambrogio, Milan, by Bramante, from 1492 details of the loggia with the tree trunk column Philip Goad Palazzo Medici, Florence, by Michelozzo di Bartolomeo, 1444-59 Pru Sanderson Palazzo dei Diamanti, Ferrara, by Biagio Rossetti, 1493 Pru Sanderson Porta Nuova, Palermo, 1535 Lewis, Architectura, p 152 Por ta Nuova, Pa lermo, Sic ily, 1535 Miles Lewis Porta Nuova, details Miles Lewis the essence of MiMannerism Mannerist tendencies exaggerating el ement s distorting elements breaking rules of arrangement joking using obscure classical precedents over-refining inventing free compositions abtbstrac ting c lass ica lfl forms suggesting primitiveness suggesting incompleteness suggesting imprisonment suggesting pent-up forces suggesting structural failure ABSTRACTION OF THE ORDERS Palazzo Maccarani, Rome, by Giulio Romano, 1521 Heydenreich & Lotz, Architecture in Italy, pl 239. Paolo Portoghesi Rome of the Renaissance (London 1972), pl 79 antistructuralism -

Discover Padua and Its Surroundings

2647_05_C415_PADOVA_GB 17-05-2006 10:36 Pagina A Realized with the contribution of www.turismopadova.it PADOVA (PADUA) Cittadella Stazione FS / Railway Station Porta Bassanese Tel. +39 049 8752077 - Fax +39 049 8755008 Tel. +39 049 9404485 - Fax +39 049 5972754 Galleria Pedrocchi Este Tel. +39 049 8767927 - Fax +39 049 8363316 Via G. Negri, 9 Piazza del Santo Tel. +39 0429 600462 - Fax +39 0429 611105 Tel. +39 049 8753087 (April-October) Monselice Via del Santuario, 2 Abano Terme Tel. +39 0429 783026 - Fax +39 0429 783026 Via P. d'Abano, 18 Tel. +39 049 8669055 - Fax +39 049 8669053 Montagnana Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 Castel S. Zeno Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 Tel. +39 0429 81320 - Fax +39 0429 81320 (sundays opening only during high season) Teolo Montegrotto Terme c/o Palazzetto dei Vicari Viale Stazione, 60 Tel. +39 049 9925680 - Fax +39 049 9900264 Tel. +39 049 8928311 - Fax +39 049 795276 Seasonal opening Mon-Sat 8.30-13.00 / 14.30-19.00 nd TREVISO 2 Sun 10.00-13.00 / 15.00-18.00 AIRPORT (sundays opening only during high season) MOTORWAY EXITS Battaglia Terme TOWNS Via Maggiore, 2 EUGANEAN HILLS Tel. +39 049 526909 - Fax +39 049 9101328 VENEZIA Seasonal opening AIRPORT DIRECTION TRIESTE MOTORWAY A4 Travelling to Padua: DIRECTION MILANO VERONA MOTORWAY A4 AIRPORT By Air: Venice, Marco Polo Airport (approx. 60 km. away) By Rail: Padua Train Station By Road: Motorway A13 Padua-Bologna: exit Padua Sud-Terme Euganee. Motorway A4 Venice-Milano: exit Padua Ovest, Padua Est MOTORWAY A13 DIRECTION BOLOGNA adova. -

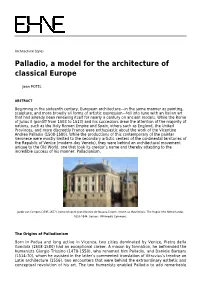

Palladio, a Model for the Architecture of Classical Europe

Architectural Styles Palladio, a model for the architecture of classical Europe Jean POTEL ABSTRACT Beginning in the sixteenth century, European architecture—in the same manner as painting, sculpture, and more broadly all forms of artistic expression—fell into tune with an Italian art that had already been renewing itself for nearly a century on ancient models. While the Rome of Julius II (pontiff from 1503 to 1513) and his successors drew the attention of the majority of nations, such as the Holy Roman Empire and Spain, others such as England, the United Provinces, and more discreetly France were enthusiastic about the work of the Vicentine Andrea Palladio (1508-1580). While the productions of this contemporary of the painter Veronese were mostly limited to the secondary artistic centers of the continental territories of the Republic of Venice (modern-day Veneto), they were behind an architectural movement unique to the Old World, one that took its creator’s name and thereby attesting to the incredible success of his manner: Palladianism. Jacob van Campen (1595-1657), home of count Jean-Maurice de Nassau-Siegen, known as Mauritshuis, The Hague (the Netherlands), 1633-1644. Source : Wikimedia Commons. The Origins of Palladianism Born in Padua and long active in Vicenza, two cities dominated by Venice, Pietro della Gondola (1508-1580) had an exceptional career. A mason by formation, he befriended the humanists Giorgio Trissino (1478-1550), who renamed him Palladio, and Daniele Barbaro (1514-70), whom he assisted in the latter’s commented translation of Vitruvius’s treatise on Latin architecture (1556), two encounters that were behind the extraordinary esthetic and conceptual revolution of his art. -

Palladio and Vitruvius: Composition, Style, and Vocabulary of the Quattro Libri

LOUIS CELLAURO Palladio and Vitruvius: composition, style, and vocabulary of the Quattro Libri Abstract After a short preamble on the history of the text of Vitruvius during the Renaissance and Palladio’s encounter with it, this paper assesses the Vitruvian legacy in Palladio’s treatise, in focusing more particularly on its composition, style, and vocabulary and leaving other aspects of his Vitruvianism, such as his architectural theory and the five canonical orders, for consideration in subsequent publications. The discussion on composition concerns Palladio’s probable plans to complete ten books, as an explicit reference to Vitruvius’ treatise. As regards style, the article highlights Palladio’s intention to produce an illustrated treatise like those of Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Sebastiano Serlio, and Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola (whereas the treatise of Vitruvius was probably almost unillustrated), and Palladio’s Vitruvian stress on brevity. Palladio is shown to have preferred vernacular technical terminology to the Vitruvian Greco-Latin vocabulary, except in Book IV of the Quattro Libri in connection with ancient Roman temples. The composition, style, and vocabulary of the Quattro Libri are important issues which contribute to an assessment of the extent of Palladio’s adherence to the Vitruvian prototype in an age of imitation of classical literary models. Introduction The De architectura libri X (Ten Books on Architecture) of the 1st-Century BCE Roman architect and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio was a text used by Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) and many other Renaissance architects both as a guide to ancient architecture and as a source of modern design. Vitruvius is indeed of great significance for Renaissance architecture, as his treatise can be considered as a founding document establishing the ground rules of the discipline for generations after its first reception in the Trecento and early Quattrocento.1 His text offers a comprehensive overview of architectural practice and the education required to pursue it successfully. -

The Acts of Augustus As Recouded on the Monumentum Ancyranum

THE ACTS OF AUGUSTUS AS RECOUDED ON THE MONUMENTUM ANCYRANUM Below is a copy of the acts of the Deified Augustus by which he placed the whole world under the sovereignty of the Roman people, and of the amounts which he expended upon the state and the Roman people, as engraved upon two bronze colimins which have been set up in Rome.<» 1 . At the age of nineteen,* on my o>vn initiative and at my own expense, I raised an army " by means of which I restored Uberty <* to the republic, which the Mausoleum of Augustus at Rome. Its original form on that raonument was probably : Res gestae divi Augusti, quibus orbem terrarum imperio populi Romani subiecit, et impensae quas in rem publicam populumque Romanum fecit. " The Greek sup>erscription reads : Below is a translation of the acts and donations of the Deified Augustus as left by him inscribed on two bronze columns at Rome." * Octa\ian was nineteen on September -23, 44 b.c. « During October, by offering a bounty of 500 denarii, he induced Caesar's veterans at Casilinum and Calatia to enlist, and in Xovember the legions named Martia and Quarta repudiated Antony and went over to him. This activity of Octavian, on his own initiative, was ratified by the Senate on December 20, on the motion of Cicero. ' In the battle of Mutina, April 43. Augustus may also have had Philippi in mind. S45 Source: Frederick W. Shipley, Velleius Paterculus, Compendium of Roman History. Res Gestae Divi Augusti, LCL (Cambridge, MA: HUP, 19241969). THE ACTS OF AUGUSTUS, I. -

The Thin White Line: Palladio, White Cities and the Adriatic Imagination

Chapter � The Thin White Line: Palladio, White Cities and the Adriatic Imagination Alina Payne Over the course of centuries, artists and architects have employed a variety of means to capture resonant archaeological sites in images, and those images have operated in various ways. Whether recording views, monuments, inscrip- tions, or measurements so as to pore over them when they came home and to share them with others, these draftsmen filled loose sheets, albums, sketch- books, and heavily illustrated treatises and disseminated visual information far and wide, from Europe to the margins of the known world, as far as Mexico and Goa. Not all the images they produced were factual and aimed at design and construction. Rather, they ranged from reportage (recording what there is) through nostalgic and even fantastic representations to analytical records that sought to look through the fragmentary appearance of ruined vestiges to the “essence” of the remains and reconstruct a plausible original form. Although this is a long and varied tradition and has not lacked attention at the hands of generations of scholars,1 it raises an issue fundamental for the larger questions that are posed in this essay: Were we to look at these images as images rather than architectural or topographical information, might they emerge as more than representations of buildings, details and sites, measured and dissected on the page? Might they also record something else, something more ineffable, such as the physical encounters with and aesthetic experience of these places, elliptical yet powerful for being less overt than the bits of carved stone painstakingly delineated? Furthermore, might in some cases the very material support of these images participate in translating this aesthetic 1 For Italian material the list is long. -

(Michelle-Erhardts-Imac's Conflicted Copy 2014-06-24).Pages

ROME MMXV Piety, Pagans and Popes CLST 370: Seminar Abroad in Rome 2015 From its foundation through its expansion as an empire, to the rise of the papacy, Rome has served as a showcase of political and religious power through art, architecture and urban form. This course will examine the Eternal City’s most significant architectural and urban sites, moving roughly in chronological order. We will discuss how individual monuments assume symbolic importance, how they serve as models of architectural style, and how the sites take on a “sacred” quality both inside and outside of a religious context. This course is intended to offer students an introduction to the city of Rome that is architectural, artistic, and topographic in nature. Excursions to Etruscan tombs, Assisi and Florence help put Rome in a larger cultural context. " Tentative Itinerary" Friday, May 29th! Arrival in Rome Benvenuto a Roma! Check into the Centro - Piazzale del Gianicolo (view of Rome) -A walk through Trastevere: Sta. Cecilia, church and underground domus; S. Francesco a Ripa; Sta. Maria; S. Pietro in Montorio (Bramante’s Tempietto)." Saturday, May 30th! Cerveteri - Tarquinia Etruscan Influences on Early Rome. Half-Day Trip to Cerveteri or Tarquinia followed by afternoon visit to the Villa " Giulia (Etruscan Museum). ! Sunday, May 31st! Circus Flaminius Foundations of Early Rome, Military Conquest and Urban Development. Isola Tiberina (cult of Asclepius/Aesculapius) - Santa Maria in Cosmedin: Ara Maxima Herculis - Forum Boarium: Temple of Hercules Victor and Temple of Portunus - San Omobono: Temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta - San Nicola in Carcere - Triumphal Way Arcades, Temple of Apollo Sosianus, Porticus Octaviae, Theatre of Marcellus. -

Evidence of Leonardo's Systematic Design Process for Palaces and Canals in Romorantin

100 Landrus Chapter 7 Evidence of Leonardo’s Systematic Design Process for Palaces and Canals in Romorantin Matthew Landrus Leonardo’s Systematic Design Process for Romorantin University of Oxford, Faculty of History and Wolfson College In early January 1517, Leonardo worked quickly to develop plans for an urban renewal of Romorantin for Francis I of France. For this last major architectural commission, Leonardo had hundreds of architectural and canal studies, as well as the assistance of Francesco Melzi, who measured streets and studied the region. For this project Leonardo could also reference his treatise on sculp- ture, painting, and architecture, although this is now lost.1 Francis I told Benve- nuto Cellini that Leonardo was a “man of some knowledge of Latin and Greek literature,” a qualification Francis likely considered important for the architect of a project that would identify Romorantin with the grandeur of ancient Rome.2 But the last time Leonardo addressed urban planning on such a com- prehensive scale was in Milan during the late 1480s. He had worked as an archi- tect for several patrons thereafter, though there is no evidence after the mid-1490s of a continuation of his initial interest in developing a palace that was part of a two-level city over a network of canals. Having lived in Rome be- tween September 1513 and late 1516, he was influenced by the Colosseum; its three stories of exterior arcades may be recognized as part of the unusual Ro- marantin palace façade design, as illustrated on Windsor RL 12292 v (Fig. 7.1). For Leonardo, the grandeur of both structures was important.3 While in Mi- lan for seventeen years, from 1483 to 1499, he studied at length optimal urban planning and the means by which the Sforza court considered Milan the new 1 Cellini acquired a copy of this treatise on “Sculpture, Painting and Architecture” in 1542 and thereafter lent it to Sebastiano Serlio.