Carol Danvers, Kamala Khan, and Ambivalence Towards Feminism in Ms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toys and Action Figures in Stock

Description Price 1966 Batman Tv Series To the B $29.99 3d Puzzle Dump truck $9.99 3d Puzzle Penguin $4.49 3d Puzzle Pirate ship $24.99 Ajani Goldmane Action Figure $26.99 Alice Ttlg Hatter Vinimate (C: $4.99 Alice Ttlg Select Af Asst (C: $14.99 Arrow Oliver Queen & Totem Af $24.99 Arrow Tv Starling City Police $24.99 Assassins Creed S1 Hornigold $18.99 Attack On Titan Capsule Toys S $3.99 Avengers 6in Af W/Infinity Sto $12.99 Avengers Aou 12in Titan Hero C $14.99 Avengers Endgame Captain Ameri $34.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Iron $14.99 Avengers Infinite Grim Reaper $14.99 Avengers Infinite Hyperion $14.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Axe Cop $15.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Dr Doo Doo $12.99 Batman Arkham City Ser 3 Ras A $21.99 Batman Arkham Knight Man Bat A $19.99 Batman Batmobile Kit (C: 1-1-3 $9.95 Batman Batmobile Super Dough D $8.99 Batman Black & White Blind Bag $5.99 Batman Black and White Af Batm $24.99 Batman Black and White Af Hush $24.99 Batman Mixed Loose Figures $3.99 Batman Unlimited 6-In New 52 B $23.99 Captain Action Thor Dlx Costum $39.95 Captain Action's Dr. Evil $19.99 Cartoon Network Titans Mini Fi $5.99 Classic Godzilla Mini Fig 24pc $5.99 Create Your Own Comic Hero Px $4.99 Creepy Freaks Figure $0.99 DC 4in Arkham City Batman $14.99 Dc Batman Loose Figures $7.99 DC Comics Aquaman Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Batman Dark Knight B $6.99 DC Comics Batman Wood Figure $11.99 DC Comics Green Arrow Vinimate $9.99 DC Comics Shazam Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Super -

Searching for Superwomen: Female Fans and Their Behavior

SEARCHING FOR SUPERWOMEN: FEMALE FANS AND THEIR BEHAVIOR _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by SOPHIA LAURIELLO Dr. Cynthia Frisby, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2017 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled SEARCHING FOR SUPERWOMEN: FEMALE FANS AND THEIR BEHAVIOR presented by Sophia Lauriello, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Cynthia Frisby Professor Amanda Hinnant Professor Lynda Kraxberger Professor Brad Desnoyer FEMALE FANS AND THEIR BEHAVIOR ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge Dr. Cynthia Frisby for all of her work and support in helping this thesis go from an idea to a finished paper. Thank you to everyone on my committee who was as enthused about reading about comic books as I am. A huge acknowledgement to the staff of Star Clipper who not only were extremely kind and allowed me to use their game room for my research, but who also introduced me to comic book fandom in the first place. A thank you to Lauren Puckett for moderating the focus groups. Finally, I cannot thank my parents enough for not only supporting dropping out of the workforce to return to school, but for letting me (and my cat!) move back home for the last year and a half. Congratulations, you finally have your empty nest. ii FEMALE FANS AND THEIR BEHAVIOR TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... -

Tsr6903.Mu7.Ghotmu.C

[ Official Game Accessory Gamer's Handbook of the Volume 7 Contents Arcanna ................................3 Puck .............. ....................69 Cable ........... .... ....................5 Quantum ...............................71 Calypso .................................7 Rage ..................................73 Crimson and the Raven . ..................9 Red Wolf ...............................75 Crossbones ............................ 11 Rintrah .............. ..................77 Dane, Lorna ............. ...............13 Sefton, Amanda .........................79 Doctor Spectrum ........................15 Sersi ..................................81 Force ................................. 17 Set ................. ...................83 Gambit ................................21 Shadowmasters .... ... ..................85 Ghost Rider ............................23 Sif .................. ..................87 Great Lakes Avengers ....... .............25 Skinhead ...............................89 Guardians of the Galaxy . .................27 Solo ...................................91 Hodge, Cameron ........................33 Spider-Slayers .......... ................93 Kaluu ....... ............. ..............35 Stellaris ................................99 Kid Nova ................... ............37 Stygorr ...............................10 1 Knight and Fogg .........................39 Styx and Stone .........................10 3 Madame Web ...........................41 Sundragon ................... .........10 5 Marvel Boy .............................43 -

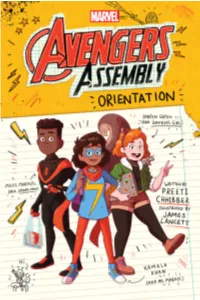

Avengersassembly Orientation

By Preeti Chhibber Illustrated by James Lancett Scholastic Inc. © 2020 MARVEL All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Inc., Publishers since 1920. scholastic and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. ISBN 978-1-338-58725-8 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 20 21 22 23 24 Printed in the U.S.A. 23 First printing 2020 Book design by Katie Fitch HERO CARD #148 powers NAME: KAMALA KHAN, AKA MS. MARVEL POWERS: Embiggening! Disembiggening! Stretching! Shape-shifting! ms. marvel HERO CARD #477 powers NAME: MILES MORALES, AKA ULTIMATE SPIDER-MAN POWERS: Wall-crawling, expo- nential strength, electric shocks, being invisible, but not being creepy like a spider, that is for sure. spider-man HERO CARD #091 powers NAME: DOREEN GREEN, AKA SQUIRREL GIRL POWERS: Powers of a squirrel and (more importantly) powers of a girl. -

An Analysis of Ms. Marvel's Kamala Khan

The “Worlding” of the Muslim Superheroine: An Analysis of Ms. Marvel’s Kamala Khan SAFIYYA HOSEIN Muslim women have been a source of speculation for Western audiences from time immemorial. At first eroticized in harem paintings, they later became the quintessential image of subservience: a weakling to be pitied and rescued from savage Brown men. Current depictions of Muslim women have ranged from the oppressed archetype in mainstream media with films such as The Stoning of Soraya M (2008) to comedic veiled characters in shows like Little Mosque on the Prairie (2012). One segment of media that has recently offered promising attempts for destabilizing their image has been comics and graphic novels which have published graphic memoirs that speak to the complexity of Muslim identity as well as superhero comics that offer a range of Muslim characters from a variety of cultures with different levels of religiosity. This paper explores the emergence of the Muslim superheroine in comic books by analyzing the most developed Muslimah (Muslim female) superhero: the rebooted Ms. Marvel superhero, Kamala Khan, from the Marvel Comics Ms. Marvel series. The analysis illustrates how the reconfiguration of the Muslim female archetype through the “worlding” of the Muslim superhero continues to perpetuate an imperialist agenda for the Third World. This paper uses Gayatri Spivak’s “worlding” which examines the “othered” natives and the global South as defined through Eurocentric terms by imperialists and colonizers. By interrogating Kamala’s representation, I argue that her portrayal as a “moderate” Muslim superheroine with Western progressive values can have the effect of reinforcing Safiyya Hosein is a Ph.D. -

PATTO – the JOHN HALSEY INTERVIEW

PATTO – the JOHN HALSEY INTERVIEW Patto, apart from being one of the finest (purely subjective, of course) bands this country ever produced, were not blessed with good fortune. Forever on the verge of making it really big, they broke up after six years of knocking on the door and finding no-one home. Subsequently, two of their number died while the other two were involved in a terrible car smash which left one with severe physical injuries and the other with severe mental problems. Drummer John Halsey is now the only Patto member who could possible give us an interview. Mike Patto and Ollie Halsall are both gone, while bassist Clive Griffiths apparently doesn't even recall being in a band! Despite bearing the scars of the accident (Halsey walks with a pronounced limp), John was only too pleased to submit to a Terrascopic grilling - an interview which took place in the wonderful Suffolk pub he runs with his wife Elaine. Bancroft and I spent a lovely afternoon and evening with the Halseys, B & B'd in the shadow of a 12th Century church cupboard and returned to London the next morning with one of the most enjoyable interviews either of us has ever done. John Halsey: I started playing drums because two mates who lived in my road in North Finchley (N. London), where I'm from, wanted to form a group. This was years and years ago, 1958, 1959. Want to see the photo? PT: Oh, look at that! 1959! Me, with a microphone inside me guitar that used to go out through me Mum's tape recorder, and if you put 'Record' and 'Play' on together, it'd act like an amplifier. -

Captain Marvel: Death of Captain Marvel Free

FREE CAPTAIN MARVEL: DEATH OF CAPTAIN MARVEL PDF Jim Starlin,Steve Englehart,Doug Moench | 128 pages | 22 Jan 2013 | Marvel Comics | 9780785168041 | English | New York, United States Death of Captain America | Marvel Database | Fandom Captain Marvel is the name of several fictional Captain Marvel: Death of Captain Marvel appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. Most of these versions exist in Marvel's main shared universeknown as the Marvel Universe. In order to retain its trademark, Marvel has published a Captain Marvel title at least once every few years since, leading to a number of ongoing serieslimited seriesand one-shots featuring a range of characters using the Captain Marvel alias. Mar-Vell eventually wearies of his superiors' malicious intent and allies himself with Earth, and the Kree Empire brands him a traitor. From then on, Mar-Vell fights to protect Earth Captain Marvel: Death of Captain Marvel all threats. He was later revamped by Roy Thomas and Gil Kane. Having been exiled to the Negative Zone by the Supreme Intelligencethe only way Mar-Vell can temporarily escape is to exchange atoms with Rick Jones by means of special wristbands called Nega-Bands. The process of the young man being replaced in a flash by the older Captain Marvel: Death of Captain Marvel was a nod to the original Fawcett Captain Marvel, which had young Billy Batson says the magic word "Shazam" to transform into the hero. With the title's sales still flagging, Marvel allowed Jim Starlin to conceptually revamp the character, [6] although his appearance was little changed. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

Costume Culture: Visual Rhetoric, Iconography, and Tokenism In

COSTUME CULTURE: VISUAL RHETORIC, ICONOGRAPHY, AND TOKENISM IN COMIC BOOKS A Dissertation by MICHAEL G. BAKER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies Texas A&M University-Commerce in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2017 COSTUME CULTURE: VISUAL RHETORIC, ICONOGRAPHY, AND TOKENISM IN COMIC BOOKS A Dissertation by MICHAEL G. BAKER Submitted to: Advisor: Christopher Gonzalez Committee: Tabetha Adkins Donna Dunbar-Odom Mike Odom Head of Department: M. Hunter Hayes Dean of the College: Salvatore Attardo Interim Dean of Graduate Studies: Mary Beth Sampson iii Copyright © 2017 Michael G. Baker iv ABSTRACT COSTUME CULTURE: VISUAL RHETORIC, ICONOGRAPHY, AND TOKENISM IN COMIC BOOKS Michael G. Baker, PhD Texas A&M University-Commerce, 2017 Advisor: Christopher Gonzalez, PhD Superhero comic books provide a unique perspective on marginalized characters not only as objects of literary study, but also as opportunities for rhetorical analysis. There are representations of race, gender, sexuality, and identity in the costuming of superheroes that impact how the audience perceives the characters. Because of the association between iconography and identity, the superhero costume becomes linked with the superhero persona (for example the Superman “S” logo is a stand-in for the character). However, when iconography is affected by issues of tokenism, the rhetorical message associated with the symbol becomes more difficult to decode. Since comic books are sales-oriented and have a plethora of tie-in merchandise, the iconography in these symbols has commodified implications for those who choose to interact with them. When consumers costume themselves with the visual rhetoric associated with comic superheroes, the wearers engage in a rhetorical discussion where they perpetuate whatever message the audience places on that image. -

Friday, March 21St Saturday, March 22Nd

Friday, March 21st Hernandez’s Recent Narratives - Derek Royal 9-10:15 AM – Panel 1: The "Body" of 4-6 PM – Dinner the Text 6-7:30 – Phoebe Gloeckner Keynote → “Time is a Man / Space is a Woman”: Narrative + Visual Pleasure = Gender 7:30-9:30 – Reception Ustler Hall Confusion – Aaron Kashtan → Eggs, Birds and “an Hour for Lunch”: A Saturday, March 22nd Vision of the Grotesque Body in Clyde Fans: Book 1 by Seth - John Kennett 9-10:15 – Panel 5: The Figure on the → Love in the Binding – Laurie Taylor Page 10:30-11:45 – Panel 2: Groensteen's → "Gimme Gimme This, Gimme Gimme Networked Relations That": Confused Sexualities and Genres in Cooper and Myerson's Horror Hospital → Memory and Sexuality: An Arthrological Unplugged – James Newlin Study of Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A → How to Draw the (DC and) Marvel Way: Family Tragicomic - Adrielle Mitchell How Changes in Representation of Female → The Joy of Plex: Erotic Arthrology, Bodies and Attitudes are Changing Tromplographic Intercourse, and "Superheroine Chic" – Mollie Dezern “Interspecies Romances” in Howard → "The Muse or the Viper: Excessive Chaykin’s American Flagg - Daniel Yezbick Depictions of the Female in Les Bas-Bleus → Our Minds in the Gutters: Native and Cerebus" – Tof Eklund American Women, Sexuality, and George O’Connor’s Graphic Novel Journey into 10:30-11:45 – Panel 7: Let's Transgress Mohawk Country - Melissa Mellon → I for Integrity: Futurity, 11:45-1:15 – Lunch (Inter)Subjectivities, and Sidekicks in Alan 1:15-2:30 – Panel 3: Women on Top Moore's V for Vendetta and Frank -

Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 Free Ebook

FREEMS. MARVEL: VOL. 2 EBOOK Adrian Alphona,Takeshi Miyazawa,G. Willow Wilson | 240 pages | 19 Apr 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785198369 | English | New York, United States Ms Marvel (Vol 2) #8 VF 1st Print Marvel Comics | eBay Marvel is the name of several fictional superheroes appearing in comic books published by Marvel Comics. The character was originally conceived as a female counterpart to Captain Marvel. Like Captain Marvel, most of the bearers of the Ms. Marvel title gain their powers through Kree technology or genetics. Marvel has published four ongoing comic series titled Ms. Marvelwith the first two starring Carol Danvers and the third and fourth starring Kamala Khan. Carol Danvers, the first character to use the moniker Ms. Marvel 1 January with super powers as result of the Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 which caused her DNA Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 merge with Captain Marvel's. As Ms. Danvers goes on to use the codenames Binary [1] and Warbird. Sharon Ventura, the second character to use the pseudonym Ms. Ventura later joins the Fantastic Four herself in Fantastic Four October and, after being hit by cosmic rays in Fantastic Four JanuaryVentura's body mutates into a similar appearance to that of The Thing and receives the nickname She-Thing. Sofen tricks Bloch into giving her the meteorite that empowers him, and she adopts both the Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 and abilities of Moonstone. Marvel, Carol Danvers, receiving a costume similar to Danvers' original Danvers wore the Warbird costume at the time. Marvel series beginning in issue 38 June until Danvers takes the title back in issue 47 January Kamala Khan, created by Sana AmanatG. -

The Transgender-Industrial Complex

The Transgender-Industrial Complex THE TRANSGENDER– INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX Scott Howard Antelope Hill Publishing Copyright © 2020 Scott Howard First printing 2020. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, besides select portions for quotation, without the consent of its author. Cover art by sswifty Edited by Margaret Bauer The author can be contacted at [email protected] Twitter: @HottScottHoward The publisher can be contacted at Antelopehillpublishing.com Paperback ISBN: 978-1-953730-41-1 ebook ISBN: 978-1-953730-42-8 “It’s the rush that the cockroaches get at the end of the world.” -Every Time I Die, “Ebolarama” Contents Introduction 1. All My Friends Are Going Trans 2. The Gaslight Anthem 3. Sex (Education) as a Weapon 4. Drag Me to Hell 5. The She-Male Gaze 6. What’s Love Got to Do With It? 7. Climate of Queer 8. Transforming Our World 9. Case Studies: Ireland and South Africa 10. Networks and Frameworks 11. Boas Constrictor 12. The Emperor’s New Penis 13. TERF Wars 14. Case Study: Cruel Britannia 15. Men Are From Mars, Women Have a Penis 16. Transgender, Inc. 17. Gross Domestic Products 18. Trans America: World Police 19. 50 Shades of Gay, Starring the United Nations Conclusion Appendix A Appendix B Appendix C Introduction “Men who get their periods are men. Men who get pregnant and give birth are men.” The official American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Twitter account November 19th, 2019 At this point, it is safe to say that we are through the looking glass. The volume at which all things “trans”