Why Wonder Woman Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

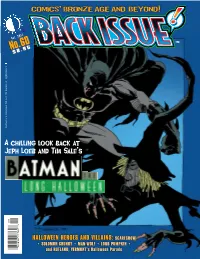

A Chilling Look Back at Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale's

Jeph Loeb Sale and Tim at A back chilling look Batman and Scarecrow TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 9 No.60 Oct. 201 2 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 COMiCs HALLOWEEN HEROES AND VILLAINS: • SOLOMON GRUNDY • MAN-WOLF • LORD PUMPKIN • and RUTLAND, VERMONT’s Halloween Parade , bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD ’ s SCARECROW i . Volume 1, Number 60 October 2012 Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! The Retro Comics Experience! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks COVER ARTIST Tim Sale COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Scott Andrews Tony Isabella Frank Balkin David Anthony Kraft Mike W. Barr Josh Kushins BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Bat-Blog Aaron Lopresti FLASHBACK: Looking Back at Batman: The Long Halloween . .3 Al Bradford Robert Menzies Tim Sale and Greg Wright recall working with Jeph Loeb on this landmark series Jarrod Buttery Dennis O’Neil INTERVIEW: It’s a Matter of Color: with Gregory Wright . .14 Dewey Cassell James Robinson The celebrated color artist (and writer and editor) discusses his interpretations of Tim Sale’s art Nicholas Connor Jerry Robinson Estate Gerry Conway Patrick Robinson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Scarecrow . .19 Bob Cosgrove Rootology The history of one of Batman’s oldest foes, with comments from Barr, Davis, Friedrich, Grant, Jonathan Crane Brian Sagar and O’Neil, plus Golden Age great Jerry Robinson in one of his last interviews Dan Danko Tim Sale FLASHBACK: Marvel Comics’ Scarecrow . .31 Alan Davis Bill Schelly Yep, there was another Scarecrow in comics—an anti-hero with a patchy career at Marvel DC Comics John Schwirian PRINCE STREET NEWS: A Visit to the (Great) Pumpkin Patch . -

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Lost Pigs and Broken Genes: The search for causes of embryonic loss in the pig and the assembly of a more contiguous reference genome Amanda Warr A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh 2019 Division of Genetics and Genomics, The Roslin Institute and Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edinburgh Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has been carried out, and the thesis composed, by the candidate Amanda Warr. Contributions by other individuals have been indicated throughout the thesis. These include contributions from other authors and influences of peer reviewers on manuscripts as part of the first chapter, the second chapter, and the fifth chapter. Parts of the wet lab methods including DNA extractions and Illumina sequencing were carried out by, or assistance was provided by, other researchers and this too has been indicated throughout the thesis. -

The Fall of Wonder Woman Ahmed Bhuiyan, Independent Researcher, Bangladesh the Asian Conference on Arts

Diminished Power: The Fall of Wonder Woman Ahmed Bhuiyan, Independent Researcher, Bangladesh The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2015 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract One of the most recognized characters that has become a part of the pantheon of pop- culture is Wonder Woman. Ever since she debuted in 1941, Wonder Woman has been established as one of the most familiar feminist icons today. However, one of the issues that this paper contends is that this her categorization as a feminist icon is incorrect. This question of her status is important when taking into account the recent position that Wonder Woman has taken in the DC Comics Universe. Ever since it had been decided to reset the status quo of the characters from DC Comics in 2011, the character has suffered the most from the changes made. No longer can Wonder Woman be seen as the same independent heroine as before, instead she has become diminished in status and stature thanks to the revamp on her character. This paper analyzes and discusses the diminishing power base of the character of Wonder Woman, shifting the dynamic of being a representative of feminism to essentially becoming a run-of-the-mill heroine. iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org One of comics’ oldest and most enduring characters, Wonder Woman, celebrates her seventy fifth anniversary next year. She has been continuously published in comic book form for over seven decades, an achievement that can be shared with only a few other iconic heroes, such as Batman and Superman. Her greatest accomplishment though is becoming a part of the pop-culture collective consciousness and serving as a role model for the feminist movement. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Why No Wonder Woman?

Why No Wonder Woman? A REPORT ON THE HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN AND A CALL TO ACTION!! Created for Wonder Woman Fans Everywhere Introduction by Jacki Zehner with Report Written by Laura Moore April 15th, 2013 Wonder Woman - p. 2 April 15th, 2013 AN INTRODUCTION AND FRAMING “The destiny of the world is determined less by battles that are lost and won than by the stories it loves and believes in” – Harold Goddard. I believe in the story of Wonder Woman. I always have. Not the literal baby being made from clay story, but the metaphorical one. I believe in a story where a woman is the hero and not the victim. I believe in a story where a woman is strong and not weak. Where a woman can fall in love with a man, but she doesnʼt need a man. Where a woman can stand on her own two feet. And above all else, I believe in a story where a woman has superpowers that she uses to help others, and yes, I believe that a woman can help save the world. “Wonder Woman was created as a distinctly feminist role model whose mission was to bring the Amazon ideals of love, peace, and sexual equality to ʻa world torn by the hatred of men.ʼ”1 While the story of Wonder Woman began back in 1941, I did not discover her until much later, and my introduction didnʼt come at the hands of comic books. Instead, when I was a little girl I used to watch the television show starring Lynda Carter, and the animated television series, Super Friends. -

Wonder Woman, Feminism and the 1972 “Women's Lib”

Wonder Woman Wears Pants: Wonder Woman, Feminism and the 1972 “Women’s Lib” Issue Ann Matsuuchi Envisioning the comic book superhero Wonder Woman as a feminist activist defending a women’s clinic from pro-life villains at first seems to be the kind of story found only in fan art, not in the pages of the canonical series itself. Such a radical character reworking did not seem so outlandish in the American cultural landscape of the early 1970s. What the word “woman” meant in ordinary life was undergoing unprecedented change. It is no surprise that the iconic image of a female superhero, physically and intellectually superior to the men she rescues and punishes, would be claimed by real-life activists like Gloria Steinem. In the following essay I will discuss the historical development of the character and relate it to her presentation during this pivotal era in second wave feminism. A six issue story culminating in a reproductive rights battle waged by Wonder Woman- as-ordinary-woman-in-pants was unfortunately never realised and has remained largely forgotten due to conflicting accounts and the tangled politics of the publishing world. The following account of the only published issue of this story arc, the 1972 Women’s Lib issue of Wonder Woman, will demonstrate how looking at mainstream comic books directly has much to recommend it to readers interested in popular representations of gender and feminism. Wonder Woman is an iconic comic book superhero, first created not as a female counterpart to a male superhero, but as an independent, title- COLLOQUY text theory critique 24 (2012). -

Costume Culture: Visual Rhetoric, Iconography, and Tokenism In

COSTUME CULTURE: VISUAL RHETORIC, ICONOGRAPHY, AND TOKENISM IN COMIC BOOKS A Dissertation by MICHAEL G. BAKER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies Texas A&M University-Commerce in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2017 COSTUME CULTURE: VISUAL RHETORIC, ICONOGRAPHY, AND TOKENISM IN COMIC BOOKS A Dissertation by MICHAEL G. BAKER Submitted to: Advisor: Christopher Gonzalez Committee: Tabetha Adkins Donna Dunbar-Odom Mike Odom Head of Department: M. Hunter Hayes Dean of the College: Salvatore Attardo Interim Dean of Graduate Studies: Mary Beth Sampson iii Copyright © 2017 Michael G. Baker iv ABSTRACT COSTUME CULTURE: VISUAL RHETORIC, ICONOGRAPHY, AND TOKENISM IN COMIC BOOKS Michael G. Baker, PhD Texas A&M University-Commerce, 2017 Advisor: Christopher Gonzalez, PhD Superhero comic books provide a unique perspective on marginalized characters not only as objects of literary study, but also as opportunities for rhetorical analysis. There are representations of race, gender, sexuality, and identity in the costuming of superheroes that impact how the audience perceives the characters. Because of the association between iconography and identity, the superhero costume becomes linked with the superhero persona (for example the Superman “S” logo is a stand-in for the character). However, when iconography is affected by issues of tokenism, the rhetorical message associated with the symbol becomes more difficult to decode. Since comic books are sales-oriented and have a plethora of tie-in merchandise, the iconography in these symbols has commodified implications for those who choose to interact with them. When consumers costume themselves with the visual rhetoric associated with comic superheroes, the wearers engage in a rhetorical discussion where they perpetuate whatever message the audience places on that image. -

Friday, March 21St Saturday, March 22Nd

Friday, March 21st Hernandez’s Recent Narratives - Derek Royal 9-10:15 AM – Panel 1: The "Body" of 4-6 PM – Dinner the Text 6-7:30 – Phoebe Gloeckner Keynote → “Time is a Man / Space is a Woman”: Narrative + Visual Pleasure = Gender 7:30-9:30 – Reception Ustler Hall Confusion – Aaron Kashtan → Eggs, Birds and “an Hour for Lunch”: A Saturday, March 22nd Vision of the Grotesque Body in Clyde Fans: Book 1 by Seth - John Kennett 9-10:15 – Panel 5: The Figure on the → Love in the Binding – Laurie Taylor Page 10:30-11:45 – Panel 2: Groensteen's → "Gimme Gimme This, Gimme Gimme Networked Relations That": Confused Sexualities and Genres in Cooper and Myerson's Horror Hospital → Memory and Sexuality: An Arthrological Unplugged – James Newlin Study of Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A → How to Draw the (DC and) Marvel Way: Family Tragicomic - Adrielle Mitchell How Changes in Representation of Female → The Joy of Plex: Erotic Arthrology, Bodies and Attitudes are Changing Tromplographic Intercourse, and "Superheroine Chic" – Mollie Dezern “Interspecies Romances” in Howard → "The Muse or the Viper: Excessive Chaykin’s American Flagg - Daniel Yezbick Depictions of the Female in Les Bas-Bleus → Our Minds in the Gutters: Native and Cerebus" – Tof Eklund American Women, Sexuality, and George O’Connor’s Graphic Novel Journey into 10:30-11:45 – Panel 7: Let's Transgress Mohawk Country - Melissa Mellon → I for Integrity: Futurity, 11:45-1:15 – Lunch (Inter)Subjectivities, and Sidekicks in Alan 1:15-2:30 – Panel 3: Women on Top Moore's V for Vendetta and Frank -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

Cohen, Comic Relief: Humor in Contemporary American Literature

Studies in English, New Series Volume 4 Article 39 1983 Cohen, Comic Relief: Humor in Contemporary American Literature Charles Sanders University of Illinois, Urbana-Champagne Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/studies_eng_new Part of the American Literature Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Sanders, Charles (1983) "Cohen, Comic Relief: Humor in Contemporary American Literature," Studies in English, New Series: Vol. 4 , Article 39. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/studies_eng_new/vol4/iss1/39 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Studies in English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English, New Series by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sanders: Cohen, Comic Relief: Humor in Contemporary American Literature SARAH BLACHER COHEN, ED. COMIC RELIEF: HUMOR IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN LITERATURE. URBANA, CHICAGO, AND LONDON: THE UNIVER SITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS, 1978. 339 pp. $15.00. The year was 1983. Praisers of the literary imagination who believed that their praises should reflect some impassioned bit of the imaginative—those artist-critic-scholar-teacher out-of-sorts like Guy Davenport, or Richards Gilman and Howard, or George Steiner, or the brothers Fussell, for whom “excellence...is ever radical”—all these had been interned upon the new Sum-thin-Else Star. (To a neighbor ing star, rumor has it, must eventually come Sanford Pinsker, Earl Rovit, Max F. Schulz, and Philip Stevick, especially if they insist on writing with a brio that places them in brilliant relief to the twelve others with whom they have presently, unfortunately, been asso ciated.) A few remaining disciples of letters and the fine arts were now relocated in the High Aesthetic Education Camp of the One Galactic University Sandbox, Inc. -

Wonder Woman by John Byrne Vol. 1 1St Edition Kindle

WONDER WOMAN BY JOHN BYRNE VOL. 1 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Byrne | 9781401270841 | | | | | Wonder Woman by John Byrne Vol. 1 1st edition PDF Book Diana met the spirit of Steve Trevor's mother, Diana Trevor, who was clad in armor identical to her own. In the s, one of the most celebrated creators in comics history—the legendary John Byrne—had one of the greatest runs of all time on the Amazon Warrior! But man, they sure were not good. Jul 08, Matt Piechocinski rated it really liked it Shelves: graphic-novels. DC Comics. Mark Richards rated it really liked it Mar 29, Just as terrifying, Wonder Woman learns of a deeper connection between the New Gods of Apokolips and New Genesis and those of her homeland of Themyscira. Superman: Kryptonite Nevermore. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. There's no telling who will get a big thrill out of tossing Batman and Robin Eternal. This story will appear as an insert in DC Comics Presents A lot of that is probably due to a general dislike for the 90s style of drawing superheroes, including the billowing hair that grows longer or shorter, depending on how much room there is in the frame. Later, she rebinds them and displays them on a platter. Animal Farm. Azzarello and Chiang hand over the keys to the Amazonian demigod's world to the just-announced husband-and-wife team of artist David Finch and writer Meredith Finch. Jun 10, Jerry rated it liked it.