The Inheritance of Coat Color in Great Danes C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French Bulldog Club Of

French Bulldog (Bouledogue Français) Coat colours according to the FCI breed standard Standard FCI N° 101 17.04.2015 Admissible Colours Faults and Disqualifications French Bulldog - FCI N° 101 Jakko BROERSMA Raerd (NL), February 2016 Admissable Colours, Faults and Disqualifications 2/15 French Bulldog - FCI N° 101 INHOUD: 1. Introduction 4 2. Admissible coat colours 5 a. Colour 6 b. Brindle 6 c. Fawn 7 d. Pied 8 e. Fawn & White 8 3. Faults 9 4. Disqualifying faults 10 a. Variations on disqualifying faults 11 b. Merle 12 5. Additional non-admissible coat colours 12 a. Red and Cream 12 b. Explanation regarding Red and Cream 13 6. Other disqualifying faults 13 a. Colour of the nose 13 7. Appendix I – Differences in translation 14 Admissable Colours, Faults and Disqualifications 3/15 French Bulldog - FCI N° 101 1. INTRODUCTION: The colour definition for the French Bulldog has been changed several times since the first FCI breed standard was written in the early 1880’s. Next to that it differs on several aspects from breed standards of other kennel clubs around the world like for instance the American Kennel Club or the English Kennel Club. Although the different standards are basically equal regarding the coat colour– the French Bulldog usually is described as fawn, brindled or pied – several details in the definitions, faults and disqualifications ensure a diversity of interpretations among the FCI, AKC, KC and other kennel clubs. The FCI breed standard for the French Bulldog was revised on several areas in 2014 and was published on April 17th in French and English. -

Official Standard of the French Bulldog General Appearance

Official Standard of the French Bulldog General Appearance: The French Bulldog has the appearance of an active, intelligent, muscular dog of heavy bone, smooth coat, compactly built, and of medium or small structure. Expression alert, curious, and interested. Any alteration other than removal of dewclaws is considered mutilation and is a disqualification. Proportion and Symmetry - All points are well distributed and bear good relation one to the other; no feature being in such prominence from either excess or lack of quality that the animal appears poorly proportioned. Influence of Sex - In comparing specimens of different sex, due allowance is to be made in favor of bitches, which do not bear the characteristics of the breed to the same marked degree as do the dogs. Size, Proportion, Substance: Weight not to exceed 28 pounds; over 28 pounds is a disqualification. Proportion - Distance from withers to ground in good relation to distance from withers to onset of tail, so that animal appears compact, well balanced and in good proportion. Substance - Muscular, heavy bone. Head: Head large and square. Eyes dark in color, wide apart, set low down in the skull, as far from the ears as possible, round in form, of moderate size, neither sunken nor bulging. In lighter colored dogs, lighter colored eyes are acceptable. No haw and no white of the eye showing when looking forward. Ears Known as the bat ear, broad at the base, elongated, with round top, set high on the head but not too close together, and carried erect with the orifice to the front. The leather of the ear fine and soft. -

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

The Show of Colours

THE SHOW OF COLOURS Celebration of every horse SHOWING CLASSES FOR ALL colour – classes for all WITH EVENING PERFORMANCE SPECTACULAR Sunday 7th July 2019 CLASSES FOR ALL HORSES AND PONIES COLOURED, TWO TONE AND SOLID £13.00 Pre entry £15.00 entry on the day Fun classes £10.00 – pre entry and on the day EVENING PERFORMANCE INCLUDING COLOUR PARADE, CLASS AND COLOUR CHAMPIONSHIPS QUALIFYING SHOW FOR CHAPS (UK) OPPORTUNITY TO GAIN POINTS FOR THE HOWE GRAND FINALE AND STEP TOWARDS THE CHANCE TO WIN £500 FOR YOURSELF AND £500 FOR YOU CHOSEN CHARITY QUALIFYING SHOW FOR OUR NEW ECOSSE ELITE TROPHY FOR SCOTTISH BREEDS THE CHANCE TO WIN £100 FOR YOURSELF AND £100 FOR YOU CHOSEN CHARITY QUALIFYING SHOW FOR THE CALEDONIAN SHOWING CHAMPIONSHIPS Please be aware that “Not Before Times” are only as a guide, classes will not start before these times but may start considerably later depending on entries Pre enter on Equo Pre entries close on 3rd July 2019 THE SHOW OF COLOURS – SUNDAY 7th JULY 2019 Welcome to the schedule of the Show of Colours which run in four rings; Ring 1 - Coloured Ring – for all Skewbald and Piebald Ring 2 -Two Tone Ring – for all Roan, Palomino, Spotted and Dun/Buckskin Ring 3 - Solid Ring – for all Black, Grey, Chestnut and Bay Ring 4 - Fun Ring - for all colours Ring 5 - TGCA Scottish Regional Show - The day of showing classes for all horses and ponies of all breeds and types will culminate in an Evening Performance Spectacular. EVENING PERFORMANCE (not before 4.30pm) CONCOURS DE ELEGANCE COLOUR PARADE Free entry – open to all please take part in hand or ridden, details on next page. -

Pigments Suitable for Encaustic

Pigments suitable for Encaustic For encaustic, pigments are melted into wax or a wax-resin-mixture. It is very important not to use toxic pigments with this technique. Pigments used for encaustic must not contain lead, arsenic or cadmium. The following list complies pigments which are heat-stable enough for this technique. However, the pigments should not be heated over the melting point of the wax and they should not be burnt. The pigments listed here are not safe for use in candle making. We recommend tests prior to the final application. Caution: Heated wax is a fire hazard and should never be left unattended. Wax vapors and fumes are hazardous for the health and should not be inhaled. An exhaust system should be installed to pull out wax vapors. Kremer-made and historic pigments 10000 - 10010 Smalt 11283 Alba Albula 10060 Egyptian Blue 11300 Red Jasper 10071 - 10072 Han-Blue 11350 Côte d'Azur Violet 10074 - 10075 Han-Purple 11360 Brown red slate 104200 Sodalite 11390 - 11392 Jade 10500 - 10580 Lapis Lazuli 11400 - 11401 Rock Crystal 11000 - 11010 Verona Green Earth 11420 - 11424 Fuchsite 11100 Bavarian Green Earth 11530 Gold Ochre from Saxony 11110 – 11111 Russische Grüne Erde 11572 - 11577 Burgundy Ochres 11140 - 11141 Aegirine 11584 - 11585 Spanish Red Ochre 11150 Epidote 11620 Brown Earth from Otranto 11200 Green Jasper 116420-116441 Moroccan Ochres 11272-11276 Ochres from Andalusia 11670 Onyx Black 11282 Nero Bernino 11674 Obsidian Black Synthetic-organic Pigments 23000 Phthalo Green Dark 23340 Isoindole Yellow 23010 Phthalo Green, -

Colorflex Standard Colors

100% PURE POLYURE A COLOR SYSTEM KANSAS CITY, USA 800.321.0906 Don't see a color that works for your project? Call VersaFlex about our custom color match program. Additional charges may apply. VF 1262 The color samples on this chart are for VF 1372 representation of color only. Colors will vary depending on viewing media. VF 1237 VF 1539 Actual cured color VF 1274 VF 1360 samples are available from VersaFlex at no VF 1089 VF 1307 VF 1275 charge upon request.* VF 1365 VF 1223 VF 1363 VF 1221 VF 1106 VF 1233 VF 1389 VF 1386 VF 1309 VF 1323 VF 1211 VF 1220 VF 1224 VF 1125 VF 1230 VF 1280 VF 1239 VF 1330 VF 1397 VF 1128 VF 1276 VF 1287 VF 1300 VF 1174 VF 1252 VF 1071 VF 1380 VF 1150 VF 1253 VF 1311 VF 1399 VF 1163 VF 1329 VF 1326 VF 1286 VF 1302 VF 1291 VF 1255 VF 1077 VF 1314 VF 1010 VF 1238 VF 1254 VF 1304 VF 1292 VF 1376 VF 1076 VF 1350 VF 1392 VF 1388 VF 1208 VF 1222 VF 1357 VF 1228 VF 1213 VF 110 4 VF 1006 VF 1005 * VersaFlex advises using actual cured samples when choosing color for projects. VF 1375 Note: These colors are not available in the GelFlex® or FSS 42D product lines. © 2016 VersaFlex Incorporated QF7.2.1a.3020 Rev 1 Date-11-21-16 VF 1005 Mesa Beige VF 1006 Antique Cork VF 1010 Forest Green VF 1286 Dark Walnut Burnt Sienna VF 1071 VF 1071 Burnt Sienna VF 1287 Tile Red Chestnut VF 1302 Enviro Green VF 1238 VF 1076 Less Brown VF 1291 Midnight Blue Eggplant VF 1314 VF 1077 Cobble Brown, Walnut VF 1292 OD Green Gold VF 1307 VF 1089 Very Light Light Grey VF 1300 Red Shade Blue Raw Sienna VF 1309 VF 110 4 Fawn Pebble VF 1302 Chestnut -

Gene C Profile Test Results

GeneGc Profile Test Results Horse: ByeMe Champagne Owner: Wendall, Jane Horse and Owner Informaon Horse ByeMe Champagne DOB 6/1/2007 Breed Paint Age 7 Color Classic Champagne Sex S Discipline Western Height 14.2 Registry APHA Reg. Number 12345 Sire Bye Bye Baby Dam Super Champagne Sire Reg. 9058-234 Dam Reg. 4314-334 Comments: Excellent Temperament Owner Wendall, Jane Address Tinseltown Phone 555-1212 City Hollywood, CA E-mail [email protected] Zip Code 91604 GeneGc Profile Test Results Horse: ByeMe Champagne Owner: Wendall, Jane Results Summary Coat Color : ByeMe Champagne has one Black allele and one Red allele making the Base coat appear Black. Also detected were single Champagne and Cream alleles; likely resulUng in a rare Champagne Cream color. One copy of the Frame Overo allele is also detected, indicang underlying white patches (hidden By CH). As a result of single gene copies in each of the following, he has a 50% chance of passing Black or Red, Cream and/or Champagne, AgouU and/or Frame Overo alleles to his offspring. Allele Summary: Aa, Ee, Ch, Cr, LWO/n Traits: ByeMe Champagne is a not a carrier of any known recessive disease genes. CauUon is recommended however, as any mare Bred to him should Be Frame Overo negave as to avoid a 25% chance of foal death (+/+ LWO results in a lethal condiUon at Birth). He may also throw Gaited foals when Bred to Gaited (+) mares. Notes: Please note that your analysis is ongoing and may include some regions marked with an asterisk denoUng the following: * Discovery – This gene detecUon is in the -

2015Coat Colour Inheritance

Article written by Jean-Marie Vanbutsele, Illustrated coat colour inheritance about the Varieties of the Belgian Shepherd Dog This is a work in progress. Genetics is a rapidly evolving field, and updates will be made. Melanocytes. How do skin, hair and iris colouring take place? In the skin, the hair and the iris there are cells that secrete pigmented granules in their environment. These cells are called melanocytes because they have a pigment named melanin. If there is an absence (or lack of activity) of melanocytes, the skin and the hair are white and the eye is red because of the presence of blood vessels. Melanocytes protect the organism against sun radiations and absorb light. Melanocytes cells secrete: either eumelanin that determine the coat, nose, lips and eyes with black colour or brown/liver/chocolate colour . either phaeomelanin that determine only the coat with yellow/red colour that covers everything from deep red (like Irish Setters) to light cream. In conclusion, all coat colours and patterns in dogs are created by these two pigments. As well as being found in the coat, eumelanin is present in the other parts of the dog that need colour – most notably the eyes (irises) and nose. Phaeomelanin is produced only in the coat. It does not occur in the eyes or the noses. In July 2009, the FCI approved a standard nomenclature for coat colour. The words “fawn” and “sand” (for diluted fawn colour) are mentioned. The translation into French of “fawn with black overlay” and “sand with black overlay” are “fauve charbonné” and “sable charbonné”. -

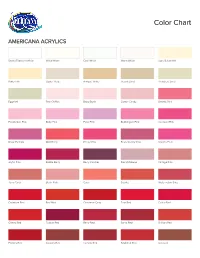

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

ARBA Official Breed ID Guide RABBIT Breed Showroom Variety Four Or

AMERICAN RABBIT BREEDERS ASSOCIATION Devoted to the Interest of Raising for Fancy and Commercial Parent Body of All Chartered Local and Specialty Clubs / One National Judging and Registration System PO Bos 5667 Bloomington, IL 61702 Phone: 309-664-7500 Fax: 309-664-0941 Email: [email protected] YOUTH COMMITTEE CHAIRPERSON Tom Berger 53382 Ironwood Rd, South Bend, IN 4635 Phone: 574-243-1183 Email: [email protected] ARBA Official Breed ID Guide RABBIT Breed Showroom Variety Four or Six Class Registration Variety American Blue, White Six Class Blue, White Chestnut, Chinchilla, Lynx, Opal, Squirrel, Black Pointed White, Blue Pointed White, Chocolate Pointed White, Lilac Pointed White, Black, Blue, Blue Eyed White, Chocolate, Lilac, Ruby Eyed White, Sable Point, Siamese Sable, Siamese Smoke American Fuzzy Lop Solid Pattern, Broken Pattern Four Class Pearl, Tortoise Shell, Blue Tortoise Shell, Fawn, Orange, Brokens are to be listed as "Broken" followed by the color comprising the broken (i.e. Broken Black, Broken Tortoise Shell, etc.) American Sable Standard Four Class Standard Black Pointed White, Blue Pointed White, Chocolate Pointed White, Lilac Pointed White, Blue Eyed White, Ruby Eyed White, Chinchilla, Chocolate Chinchilla, Lilac Chinchilla, Squirrel, Chestnut, Chocolate Agouti, Copper, English Angora Colored, White Four Class Lynx, Opal, Black, Blue, Chocolate, Lilac, Sable Pearl, Black Pearl, Blue Pearl, Chocolate Pearl, Lilac Pearl, Sable, Seal, Smoke Pearl, Blue Tortoiseshell, Chocolate Tortoiseshell, Lilac Tortoiseshell, Tortoiseshell, -

Genetic Test Results

Genetic Profile Test Results HORSE ID: 041418 003 Horse: Merlin PACK: 1 Owner: Alecia Baxley Horse and Owner Information Horse Merlin DOB 2018-04-04 Breed Paint (Overo) Age 0 years, 0 months Color Chestnut/Overo Sex Stallion Discipline Halter Height . Registry APHA Reg Number Pending Sire Ententions Dam Shes Forever Cool Sire Reg & No. Quarter 5605512 Dam Reg & No. APHA 996357 Comments . Owner Alecia Baxley Address 968 County Road 2117 Phone 281 592 6550 City, State Cleveland, TX Email [email protected] Postal Code 77327 [email protected] 650.380.2995 www.EtalonDx.com Genetic Profile Test Results HORSE ID: 041418 003 Horse: Merlin PACK: 1 Owner: Alecia Baxley Results Summary Coat Color: Merlin has two Red alleles and no Black, indicating his base coat color appears Red. One Dominant White 20 allele and one Frame/Lethal White Overo allele was also detected which may result in White markings. As a result of the allele count in each of the following, he has a minimum 100% chance of passing Red, and 50% Dominant White 20 and/or Frame/Lethal White Overo to any offspring. Allele aa, ee, W20/n, LWO/n, HYPP/n, CC (Sprint Type) Summary: Traits: Merlin's testing indicated the presence of one Frame/Lethal White Overo (LWO) allele resulting in “Carrier” status. Caution is recommended when breeding to avoid another carrier and thus, 25% chance of foal death. His testing also indicated the presence of one Hyperkalemic Periodic Paralysis (HYPP) allele indicating “Carrier” and “Possibly Affected” status. Please consult with your veterinarian regarding any medical questions or advice. -

French Bulldog Coat Colour Genetics - Feb 2008

FRENCH BULLDOG COAT COLOUR GENETICS - FEB 2008 by Dr Karen Hedberg BVSc This is a very interesting field that is undergoing some changes as the actual genes that affect colour are beginning to be located on the chromosomes. DNA specific tests can now be carried out for the presence of most of the colour alleles, particularly where one wants to know if there are unwanted dilution factors hiding within individuals. While it can look very complicated, try to understand the subject and thus produce the colours you want from matings, and not waste litters with incorrect colours. Knowledge of your proposed breeding pairs‟ colour genetics can help maximise desired colour combinations. General information Melanocytes are the cells that produce skin and hair colour and they are derived from neural crest cells. These cells arise along the back very early in foetal development and then give rise to a number of cell types, including a large proportion of the peripheral nervous system. If there is a decrease in the number of neural crest cells, other cell types are favored, leading to a reduction in melanocyte formation (see below). The melanoblasts (immature colour cells) migrate from the dorsal midline over the surface of the body, so the last areas to be reached are the feet, chest and muzzle (ie where you are more likely to see white toes, etc). Neural crest cells also form part of the nervous system for the inner ear and eye. Animals selected for extreme white spotting (eg. Dalmatians) can have hearing and/or vision problems in other extreme white patterns (merle series).