The Marketing Book, Sixth Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCMS 2019 Conference Program

CELEBRATING SIXTY YEARS SCMS 1959-2019 SCMSCONFERENCE 2019PROGRAM Sheraton Grand Seattle MARCH 13–17 Letter from the President Dear 2019 Conference Attendees, This year marks the 60th anniversary of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies. Formed in 1959, the first national meeting of what was then called the Society of Cinematologists was held at the New York University Faculty Club in April 1960. The two-day national meeting consisted of a business meeting where they discussed their hope to have a journal; a panel on sources, with a discussion of “off-beat films” and the problem of renters returning mutilated copies of Battleship Potemkin; and a luncheon, including Erwin Panofsky, Parker Tyler, Dwight MacDonald and Siegfried Kracauer among the 29 people present. What a start! The Society has grown tremendously since that first meeting. We changed our name to the Society for Cinema Studies in 1969, and then added Media to become SCMS in 2002. From 29 people at the first meeting, we now have approximately 3000 members in 38 nations. The conference has 423 panels, roundtables and workshops and 23 seminars across five-days. In 1960, total expenses for the society were listed as $71.32. Now, they are over $800,000 annually. And our journal, first established in 1961, then renamed Cinema Journal in 1966, was renamed again in October 2018 to become JCMS: The Journal of Cinema and Media Studies. This conference shows the range and breadth of what is now considered “cinematology,” with panels and awards on diverse topics that encompass game studies, podcasts, animation, reality TV, sports media, contemporary film, and early cinema; and approaches that include affect studies, eco-criticism, archival research, critical race studies, and queer theory, among others. -

Language of Money Arun Anant Sameer Nair

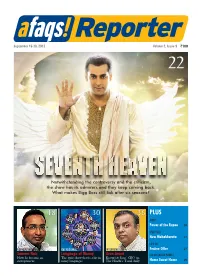

September 16-30, 2013 Volume 2, Issue 9 `100 22 NotwithstandingN t ith t di theth controversyt andd theth criticism,iti i the show has its admirers and they keep coming back. What makes Bigg Boss still tick after six seasons? 18 8 30 36 PLUS AIRTEL Power of the Rupee 10 STAR PLUS New Mahabharata 27 LIFE OK DEFINING MOMENTS KBC REGIONAL INTERVIEW Festive Offer 27 Sameer Nair Language of Money Arun Anant COLORS/ASIAN PAINTS How he became an The quiz show that is a hit in Kasturi & Sons’ CEO on entrepreneur. many languages. The Hindu’s Tamil daily. Home Sweet Home 29 EDITORIAL This fortnight... Volume 2, Issue 9 am embarrassed by just how many times I have watched the English film, Gladiator. I Because I like Russell Crowe, I enjoy catching it on TV whenever I can. Watching EDITOR September 16-30, 2013 Volume 2, Issue 9 `100 an action film can be curiously relaxing when you can anticipate each bit of violence Sreekant Khandekar 22 and every drop of blood. Whenever I view an especially gory sequence with screaming PUBLISHER Roman hordes in the Colosseum, I think to myself, ‘Ah, the reality show of their times’. Prasanna Singh SENIOR LAYOUT ARTIST I may not be an ardent viewer of reality shows but, to my mind, the parallel between Vinay Dominic the then and the now is unmistakable. In those days, gladiatorial contests kept the PRODUCTION EXECUTIVE citizens occupied and they presumably went back home with the satisfaction of having Andrias Kisku witnessed someone’s extreme – and generally terminal - physical agony. -

Whitepaper Version 3.0 August 21St, 2017

AirToken (AIR) The token for mobile access Mobile accessibility using advertising and token-spotting on the blockchain AirFox Whitepaper Version 3.0 August 21st, 2017 Contents 1. Executive Summary 2. Introduction 3. The Problem 3.1. User Scenarios 4. The Solution 5. Target Market 6. AirFox Wireless 6.1. Technology 7. Dead Mobile Capital 8. Company 8.1. Management Team 8.2. Investors 8.3. Advisors 9. AirFox Pillars of Mobile Access 10. Business Landscape 10.1. Prepaid Market & Internet Affordability 10.2. The underbanked and unbanked 10.3. Mobile Economy Accessibility 11. AirToken Platform 11.1. Android Applications 11.1.1. AirFox Browser 11.2. AirToken Spotting 11.3. Telco & Advertiser Integrations 11.4. Reward System 11.5. AirToken Protocols 12. Product Roadmap 13. AIR Mechanics 13.1. Internal AIR Ledger 13.2. AirTokens in an Ethereum Account to the AirFox Internal AIR Ledger 13.3. AIR Exchange Rate 13.4. AIR Market Flow 13.5. AirFox Server Architecture 14. Competitors 15. Telco incentives and bulk data purchases 16. Token Launch 17. AirToken (AIR) FAQ 18. Citations 1 Executive Summary AirToken (AIR) - The Token for Mobile access ● 1.8 billion people operate in a $10 trillion underground economy ● 2 billion people unbanked ● 4 billion people have yet to receive internet access due to mobile affordability ● 80% of the world is on a prepaid phone using on average 500MB of data / month ● Billions more underserved by their local banks, telcos, and governments AirFox’s vision is to make the mobile internet more affordable and accessible and the biggest limitation for our customers is access to capital. -

How Technology Makes Creative More Intelligent

How Technology Makes Creative More Intelligent WRITTEN BY Pete Crofut THE RUNDOWN PUBLISHED January 2014 Today’s technology can target and customize ads with unparalleled precision. At the same time, busy consumers expect ads to be both incredibly compelling and highly relevant. So while the opportunity is bigger than ever, the stakes are higher too. Adding to this are technological obstacles. With consumers using multiple devices, creative must seamlessly move across them. Marketers also need to measure and optimize faster than ever. As part of The Engagement Project, Google's Creative Platforms Evangelist, Pete Crofut, talks about how new tools and platforms can address these challenges, helping you create “intelligent” ads—ones that are engaging and meaningful in the moments that matter. thinkinsights Intelligent, engaging, creative. This may sound like a personal ad, but it’s also the future of ads in general. In fact, advertising is getting more personal, more engaging, more interesting and more thought-provoking than ever. Today’s technology can target and customize ads with unparalleled precision. At the same time, busy consumers expect ads to be both incredibly compelling and highly relevant, and thus meaningful to them at that moment. This means that while the opportunity is bigger than ever, the stakes are higher too. If your brand “matches” with a potential consumer, you might have one chance to make a first impression, so it had better be a good one. Adding to this are technological obstacles. With consumers using multiple devices, creative must seamlessly move across smartphones, desktops and tablets, a demand that can seem daunting to marketers inexperienced with HTML5 and the coding needed for such content. -

El Caso De La Youtuber Zoella

Facultat de Ciències de la Comunicació Treball de fi de grau Títol Autor/a Tutor/a Departament Grau Tipus de TFG Data Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Facultat de Ciències de la Comunicació Full resum del TFG Títol del Treball Fi de Grau: Català: Castellà: Anglès: Autor/a: Tutor/a: Curs: Grau: Paraules clau (mínim 3) Català: Castellà: Anglès: Resum del Treball Fi de Grau (extensió màxima 100 paraules) Català: Castellà: Anglès: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona ANÁLISIS DE UN CANAL DE YOUTUBE El caso de la youtuber Zoella Nuria Lite Muñoz Tutor: Ezequiel Ramón Trabajo de Final de Grado - Periodismo Índice del trabajo 1. Introducción…………………………………………………...…………………….página 1 1.1 Objeto de estudio…………………………………………………...………….página 2 1.2 Objetivos…………………………………………………………………..…….página 2 1.3 Preguntas iniciales e hipótesis…………………………………………….….página 3 2. Marco teórico………………………………………………………………………..página 4 2.1 ¿Qué es YouTube? ………………………………….………………………...página 4 2.1.1 La historia de YouTube……………………………………..…...….página 6 2.1.2 Factores del crecimiento de YouTube…………………………….página 8 2.1.2.1 Google compra YouTube……………………………..….página 8 2.1.3 Público objetivo de YouTube……………………………………….página 9 2.1.4 YouTube vs. Televisión planetaria………………………………...página 9 2.1.5 YouTube como modelo de negocios………………………….....página 11 2.1.5.1 ¿Cómo gana un usuario dinero en YouTube?....…….página 12 2.2 ¿Qué es un youtuber? ………………………………………………….…....página 13 3. Metodología…………………………………………………………….……….….página 21 4. Investigación de campo……………………………………………….…….…….página 25 4.1 -

Subscribe to Amusement Today (817) 460-7220

INSIDE: TM & ©2014 Amusement Today, Inc. Knott’s preserves fruit spread tradition — PAGE 42 July 2014 | Vol. 18 • Issue 4 www.amusementtoday.com Kentucky Kingdom returns with successful re-opening STORY: Tim Baldwin [email protected] LOUISVILLE, Ky. — Fol- lowing a preview weekend, Kentucky Kingdom reopened its gates, and residents of Lou- isville could once again enjoy amusement park thrills in their hometown. Dormant since 2010, rumors circulated for years with various proposals surfacing to reopen the park. Finally, a new life for the park officially began on May 24, 2014. Returning fans, or those who were simply curi- ous, found much among the line-up to offer brand new fam- ily fun. Top row, l to r: Overbanked turns and airtime hills thrill riders on the new Lightning Run roller coaster from Chance Rides. Guests control their own ride the Larson-built Professor John’s Flying Machines. Bottom row, l to r: Zamperla’s new Rock-A- The past Bye swings ride takes the old porch swing to a whole new level. Guests can choose from three different water slide experi- There aren’t many parks ences on the Wikiwiki slide complex from ProSlide. AT/GARY SLADE & TIM BALDWIN that have quite the storied past claimed by Kentucky Kingdom. Its actual origins began in 1987, as a small group of inves- tors wished to develop leased Hart property on the Kentucky State Fairgrounds into more of a regional amusement park. A small assortment of rides occupied 10 acres, but the venture only lasted a year before falling into financial ruin. -

Essay About Youtube History

1 Essay About Youtube History In January 2019, AutoShare was removed. 16 Chen made sure the page actually worked and that there would be no issues with the uploading and playback process. YouTube s early website layout featured a pane of currently watched videos, as well as video listings with detailed information such as full 2006 and later expandable 2007 descriptions, as well as profile pictures 2006 , ratings, comment counts, and tags. 183 URLs to YouTube were redirected to China s own search engine, Baidu. Records and was cited as the first brand channel on the platform. YouTube was blocked from Mainland China from October 18 due to the censorship of the Taiwanese flag. It offers a wide variety of user-generated and corporate media videos. 34 35 Channels pages were equipped with standalone view counters, bulletin boards, and were awarded badges for various rank-based achievements, such as 15 - Most Subscribed This Month , 89 - Most Subscribed All Time , and 15 - Most Viewed This Week. 31 In 2007, both Sports Illustrated and Dime Magazine featured positive reviews of a basketball highlight video titled, The Ultimate Pistol Pete Maravich MIX. 88 89 Both events were met with negative to mixed reception. In June 2007, YouTube launched a mobile web front end, where videos are served through RTSP. 19 It was ranked the fifth-most-popular website on Alexa, far out-pacing even MySpace s rate of growth. In early 2009, YouTube registered the domain www. The increasing copyright infringement problems and lack in commercializing YouTube eventually led to outsourcing to Google who recently had just failed in their own video platform. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Social Media Marketing: Mediale Praxis, Ästhetik und Technologie am Beispiel der Video-Community YouTube“ Verfasser Michael Hintringer angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. habil. Ramón Reichert Danksagung Mein Dank geht an meinen Diplomarbeitsbetreuer Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. habil. Ramón Reichert, meine Eltern, meine Schwester, an Manuela und an Michael für Unterstützung, Anregungen, Diskussionen und Wegbegleitung. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Eine einführende Betrachtung ......................................................................................... 11 2. Der Versuch einer Definition ........................................................................................... 17 2.1. Fokussierung der NutzerInnen im historischen Kontext .......................................... 18 2.2. Hierarchische Strukturen als NutzerInnendefinition ................................................ 19 2.2.1. NutzerInnen als AmeturInnen ............................................................................ 19 2.2.2. Das unternehmerische Selbst ............................................................................. 23 2.2.3. Formen der Inhaltsproduktion ........................................................................... 26 3. Immaterielle Arbeit ......................................................................................................... -

Pdf Why Am I Seeing This?

March 2020 Why Am I Seeing This? How Video and E-Commerce Platforms Use Recommendation Systems to Shape User Experiences Spandana Singh Last edited on March 25, 2020 at 12:26 p.m. EDT Acknowledgments In addition to the many stakeholders across civil society and industry who have taken the time to talk to us about ad targeting and delivery over the past few months, we would particularly like to thank Dr. Nathalie Maréchal from Ranking Digital Rights for her help in closely reviewing and providing feedback on this report. We would also like to thank Craig Newmark Philanthropies for its generous support of our work in this area. newamerica.org/oti/reports/why-am-i-seeing-this/ 2 About the Author(s) Spandana Singh is a policy analyst in New America's Open Technology Institute. About New America We are dedicated to renewing America by continuing the quest to realize our nation’s highest ideals, honestly confronting the challenges caused by rapid technological and social change, and seizing the opportunities those changes create. About Open Technology Institute OTI works at the intersection of technology and policy to ensure that every community has equitable access to digital technology and its benefits. We promote universal access to communications technologies that are both open and secure, using a multidisciplinary approach that brings together advocates, researchers, organizers, and innovators. newamerica.org/oti/reports/why-am-i-seeing-this/ 3 Contents Introduction 6 An Overview of Algorithmic Recommendation Systems 8 Case Study: YouTube -

Remembering Freddie Hubbard's Fast, Brash, Brilliant

DB0409_001_COVER.qxd 2/12/09 9:38 AM Page 1 DOWNBEAT FREDDIE HUBBARD JON HASSELL ROY ELDRIDGE MARTIAL SOLAL ELDRIDGE JON HASSELLFREDDIE HUBBARD ROY DownBeat.com $4.99 04 APRIL 2009 0 09281 01493 5 APRIL 2009 U.K. £3.50 DB0409_002-005_MAST.qxd 2/11/09 2:51 PM Page 2 DB0409_002-005_MAST.qxd 2/11/09 2:52 PM Page 3 DB0409_002-005_MAST.qxd 2/12/09 11:32 AM Page 4 April 2009 VOLUME 76 – NUMBER 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Jason Koransky Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser Intern Mary Wilcop ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 www.downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 800-554-7470 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

Youtubers' Impact on Viewers' Buying Behavior

YouTubers’ impact on viewers’ buying behavior Emmi-Julia Lepistö Miina Vähäjylkkä Bachelor’s Thesis May 2017 Social Sciences, Business and Administration Degree Programme in International Business Description Author(s) Type of publication Date Lepistö, Emmi-Julia Bachelor’s thesis 8.5.2017 Vähäjylkkä, Miina Number of pages Language of publication: 71 English Permission for web publi- cation: x Title of publication YouTubers’ impact on viewers’ buying behavior Degree programme Degree Programme in International Business Supervisor(s) Luck, Heidi Assigned by Description YouTubers have achieved a status as one of the biggest influencers in social media, gaining a wide, loyal audience to support them. Celebrity endorsement has been around for years, however, with the rise of YouTubers’ fame, companies have taken this as an opportunity to influence a new audience and gain visibility to their brand. The aim of the thesis was to examine the influence Finnish female lifestyle YouTubers have on their viewers buying behavior, what is their decision-making process and what are the external factors influencing their buying behavior. The goal was to provide valuable infor- mation for viewers, YouTubers themselves and content providers as they work together with YouTubers to market their brand. The research was carried out using qualitative approach as eight semi-structured interviews were conducted. The sample was formed of Finnish female lifestyle YouTubers’ viewers be- tween the ages of 16 to 23. The respondents were interviewed for their conceptions on their purchase behavior and habits as well as their thoughts on YouTubers and the impact they have on them. The data provided was recorded and transcribed for the analysis phase. -

The BG News December 11, 2017

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 12-11-2017 The BG News December 11, 2017 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation State University, Bowling Green, "The BG News December 11, 2017" (2017). BG News (Student Newspaper). 9015. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/9015 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. bg MAZEY news An independent student press serving the campus and surrounding community, ESTABLISHED 1920 Bowling Green State University Monday December 11, 2017 MOVES ON Volume 97, Issue 36 Death rates Hockey splits How to make rise at the U.S. - seventh series delicious holiday Mexico border of season cocktails PAGE 3 PAGE 8 PAGE 11 PHOTO BY VIKTORIIA YUSHKOVA t we get it. COLLEGE [email protected] www.bgsu.edu/sls HAPPENS 419-372-2951 STUDENT LEGAL SERVICES REAL LAWYERS | REAL RESULTS BG NEWS December 11, 2017 | PAGE 2 President Mazey announces her resignation Brionna Scebbi as the Master Plan and an increased re- Reporter tention rate, over the past seven years with the status of president emerita. University President Mary Ellen Mazey “I cannot thank you enough for ev- shocked students by announcing her res- erything you have done,” Megan Newlove, ignation, effective Dec.