Masters of Scale Episode Transcript – Richard Branson “The Secret to Big

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ratner Kills Mr

Brooklyn’s Real Newspaper BrooklynPaper.com • (718) 834–9350 • Brooklyn, NY • ©2008 BROOKLYN HEIGHTS–DOWNTOWN–NORTH BROOKLYN AWP/18 pages • Vol. 31, No. 8/9 • Feb. 23/March 1, 2008 • FREE INCLUDING CARROLL GARDENS, COBBLE HILL, BOERUM HILL, DUMBO, WILLIAMSBURG AND GREENPOINT RATNER KILLS MR. BROOKLYN By Gersh Kuntzman EXCLUSIVE right now,” said Yassky (D– The Brooklyn Paper Brooklyn Heights). “Look, a lot of developers are re-evalut- Developer Bruce Ratner costs had escalated and the num- ing their numbers and feel that has pulled out of a deal with bers showed that we should residential buildings don’t City Tech that could have net not go down that road,” added work right now,” he said. him hundreds of millions of the executive, who did not wish Yassky called Ratner’s dollars and allowed him to to be identified. withdrawal “good news” for build the city’s tallest resi- Costs had indeed escalated. Brooklyn. dential tower, the so-called In 2005, CUNY agreed to pay “A residential building at Mr. Brooklyn, The Brooklyn Ratner $86 million to build the that corner was an awkward Paper has learned. 11- to 14-story classroom-dor- fit,” said Yassky. “A lot of plan- “It was a mutual decision,” mitory and also to hand over ners see that site as ideal for a said a key executive at the City the lucrative development site significant office building.” University of New York, which where City Tech’s Klitgord Forest City Ratner did not would have paid Ratner $300 Auditorium now sits. return two messages from The million to build a new dorm Then in December, CUNY Brooklyn Paper. -

Alternative Routes and Ticket Acceptance During Disruption on Virgin Trains West Coast See Map Page 2

Alternative routes and ticket acceptance during disruption on Virgin Trains West Coast see map page 2 Virgin route Alternative route Operator Euston - West Midlands Marylebone - West Midlands Chiltern Railways Paddington - Reading / Oxford First Great Western Reading / Oxford - West Midlands CrossCountry Euston - North Wales Birmingham / Crewe / Wrexham - Holyhead Arriva Trains Wales Euston - Manchester St Pancras - Sheffield East Midlands Trains Sheffield - Manchester TransPennine Express / Northern King’s Cross - Leeds - Manchester Virgin Trains East Coast / TransPennine Express / Northern Euston - Liverpool Birmingham - Liverpool London Northwestern Chester - Liverpool Merseyrail Euston - Preston and Scotland King’s Cross - Newcastle / Scotland Virgin Trains East Coast West Midlands - York - Scotland CrossCountry Birmingham - Preston and Scotland West Midlands - York - Scotland CrossCountry Virgin WC alternative routes 6 29/11/17 www.projectmapping.co.uk Dyce Kingussie Spean Aberdeen Glenfinnan Bridge Mallaig Blair Atholl Fort Stonehaven William Rannoch Montrose Pitlochry Arbroath Tyndrum Oban Dalmally Alternative Crianlarichroutes and ticket acceptancePerth Dundee Gleneagles Cupar Dunblane during disruptionArrochar & Tarbet on Virgin Trains West Coast Stirling Dunfermline Kirkcaldy Larbert Alloa Inverkeithing Garelochhead Falkirk Balloch Grahamston EDINBURGH Helensburgh Upper Polmont Waverley Milngavie North Berwick Helensburgh Central Lenzie Falkirk Bathgate Dunbar High Dumbarton Central Maryhill Haymarket Westerton Springburn Cumbernauld -

![Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd V Sharman Networks Ltd [2006] FCAFC 41 (23 March 2006)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5316/universal-music-australia-pty-ltd-v-sharman-networks-ltd-2006-fcafc-41-23-march-2006-365316.webp)

Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd V Sharman Networks Ltd [2006] FCAFC 41 (23 March 2006)

Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Sharman Networks Ltd [2006] FCAFC 41 (23 March 2006) Last Updated: 23 March 2006 FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Sharman Networks Ltd [2006] FCAFC 41 CONTEMPT OF COURT – question of law referred by primary judge to Full Court – question whether, ‘having regard to nature and terms of’ order alleged to have been disobeyed, a determination of contempt may be made in respect of the contraventions alleged in the statement of charge – order the subject of pending appeal – order must be obeyed until set aside – different possible meanings of ‘equivocal’ and ‘ambiguous’ in relation to orders in earlier cases on contempt – discussion of orders whose meaning is obscure as a matter of construction of their terms, and orders shown to be uncertain or ambiguous in their operation in the context of the facts proved by the evidence – referred question answered, Yes. Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s 25(6) Federal Court Rules O 37 r 2 Australian Consolidated Press Ltd v Morgan (1965) 112 CLR 483 considered Coflexip SA v Stolt Comex Seaway MS Ltd [1999] FSR 473 cited Commodore Business Machines Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1990) 92 ALR 563 cited Commonwealth Industrial Gases Ltd v M.W.A. Holdings Pty Ltd (1970) 180 CLR 160 cited Iberian Trust Ltd v Founders Trust and Investment Co [1932] 2 KB 87 considered ICI Australia Operations Pty Limited v Trade Practices Commission (1992) 38 FCR 248 referred to Interlego A.G. v Toltoys Pty Ltd (1973) 130 CLR 461 cited Johnson v Walton -

Who's Who in A&R at Virgin Records

WHO'S WHO IN A&R AT VIRGIN RECORDS INTRODUCTION In examining Virgin Records as it relates to America, it must be noted that there are basically two operations, Virgin-United States and Virgin-International. The former is managed by Charles Dimont. The latter operation falls under the jurisdiction of Simon Draper and is based in London. Virgin-U.S., based in New York, is primarily a filter and servicing office for the larger International operation. Charles notes that the U.S. releases include approximately 20 acts, although International maintains some 30 groups. In discussing the composition of the roster and current trends, Charles emphasizes that, "we want to give the label shape and balance." He sees too many bands playing formula music whereas Virgin is seeking a different, original sound. Although the label is looking for such a balance, Dimont interjects that, "we would not feel comfortable signing an r&b act or a singer-songwriter." While International has some 4-5 reggae acts and an a&r executive to oversee that department, Dimont says that, "there is no indication as yet that reggae will happen in the U.S., 'New Wave' is in fashion," but he regards pop as a marketable and pro- grammable style. In terms of his own roster, Charles points out that, "our acts are not necessarily pro- grammable or sellable, but all are class — on the frontier of commerciality." In regard to unsolicited tapes, Dimont stresses that because there is no formal a&r situation in New York, they all listen. Virgin-U.S. -

The Width of Infinity Is a House Squatting on an Unnamed Street

THE WIDTH OF INFINITY IS A HOUSE SQUATTING ON AN UNNAMED STREET A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the DeGree Master of Fine Arts Joel Lee May, 2011 THE WIDTH OF INFINITY IS A HOUSE SQUATTING ON AN UNNAMED STREET Joel Lee Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Mary Biddinger Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Michael Dumanis Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Department Chair Mr. David Giffels Dr. Michael Schuldiner _______________________________ Date ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTERRUPTING THE MEETING OF HUMAN DEFINITION AND BIBLICAL PROPORTIONS……………………………………………………………………………………………………...1 THE FEAR OF BEING LEFT ALONE………………………………………………………………………..2 A SHORT AUTOBIOGRAPHY, WITH LOVE……………………………………………………………...4 SAVE THE TRAUMA FOR YOUR MAMA………………………………………………………………….5 THE DISPERSAL PATTERN OF RECENTLY TRAFFICJAMMED VEHICLES………………...6 HOLY FUCKING SHIT, WORDS ARE STILL WORDS EVEN AFTER THE ALPHABET RETIRED……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...8 SOMEBODY IS PROBABLY STILL ALIVE SOMEWHERE, EVEN IF THERE IS NOTHING LEFT………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….10 WHEN YOU’VE BECOME YOUR FATHER, THAT’S WHEN YOU EMBRACE EUTHANASIA……………………………………………………………………………………………………..12 AND THIS IS WHERE YOU PICK UP THE MACHINE GUN………………………………………14 -

CASE STUDY: VIRGIN TRAINS How Spherica Helped Virgin Trains Move Its Data Centre Infrastructure to Microsoft Azure in Record Time

CASE STUDY: VIRGIN TRAINS How Spherica helped Virgin Trains move its data centre infrastructure to Microsoft Azure in record time Virgin Trains is one of the largest train operating companies in the UK and is owned by Virgin Rail Group. It operates long-distance passenger services on the West Coast Main Line between London, West Midlands, North West England, North Wales and Scotland. And, it connects six of the UK’s largest cities - London, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and Edinburgh. With more than 3,500 employees, carrying 34.5 million passengers a year across 23 stations – with its head office located in London Euston and major operations in Birmingham - effective communication and a strong IT infrastructure is key to keep the business running at optimal levels. +44 (0)845 862 1794 | [email protected] | WWW.SPHERICA.CO.UK Case Study: Virgin Trains Data Centre Migration THE CHALLENGE THE SOLUTION In July 2017, Virgin Trains was notified by its data Virgin Trains had two options. It could either move centre provider that it would be closing down its to a new data centre with its current provider, or current centre. use the opportunity to take advantage of new technologies. The data centre had provided the home for Virgin Trains’ entire back end infrastructure since 2013, The IT team could see the opportunity that the which included rail applications that were critical to forced move presented and saw the data centre its business operations. move as a positive, enlisting long term partner Spherica to help migrate its systems to Microsoft In addition, the centre announced it would close Azure. -

REPUTATION MANAGEMENT Gaining Control of Issues, Crises & Corporate Social Responsibility

new strategic_TP:Layout 1 12/9/07 11:11 Page 1 NEWSTRATEGIESFOR REPUTATION MANAGEMENT Gaining Control of Issues, Crises & Corporate Social Responsibility ANDREW GRIFFIN London and Philadelphia Publisher’s note Every possible effort has been made to ensure that the information contained in this book is accurate at the time of going to press, and the publishers and author cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions, however caused. No responsibility for loss or damage occasioned to any person acting, or refraining from action, as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by the editor, the publisher or the author. First published in Great Britain and the United States in 2008 by Kogan Page Limited. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms and licences issued by the CLA. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside these terms should be sent to the publishers at the undermentioned addresses: 120 Pentonville Road 525 South 4th Street, #241 London N1 9JN Philadelphia PA 19147 United Kingdom USA www.kogan-page.co.uk © Andrew Griffin, 2008 The right of Andrew Griffin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. ISBN 978 0 7494 5007 6 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Virgin Mobile Holdings (Uk)

A copy of this document, comprising listing particulars relating to Virgin Mobile Holdings (UK) plc (the Company) prepared solely in connection with the proposed offer to certain institutional and professional investors (the Global Offer) of ordinary shares (the Ordinary Shares) in the Company in accordance with the Listing Rules made under section 74 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA), has been delivered for registration to the Registrar of Companies in England and Wales pursuant to section 83 of FSMA. Application has been made to the UK Listing Authority for the ordinary share capital of Virgin Mobile Holdings (UK) plc to be admitted to the Official List of the UK Listing Authority and to the London Stock Exchange for such share capital to be admitted to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s market for listed securities. It is expected that admission to listing and trading will become effective and that unconditional dealings will commence at 8.00 a.m. on 26 July 2004. All dealings in Ordinary Shares prior to the commencement of unconditional dealings will be on a ‘‘when issued’’ basis and of no effect if Admission does not take place and will be at the sole risk of the parties concerned. The Directors of Virgin Mobile Holdings (UK) plc, whose names appear on page 8 of this document, accept responsibility for the information contained in this document. To the best of the knowledge and belief of the Directors (who have taken all reasonable care to ensure that such is the case), the information contained in this document is in accordance with the facts and does not omit anything likely to affect the import of such information. -

Virgin Trains Makes Finding the Cheapest Fare Easier Than Ever with New Industry-Leading Website Submitted By: Morris & Company Tuesday, 20 March 2007

Virgin Trains makes finding the cheapest fare easier than ever with new industry-leading website Submitted by: Morris & Company Tuesday, 20 March 2007 Virgin Trains is leading the railway industry with its new website designed to make searching and buying the cheapest possible ticket far simpler. The site provides customers with a one-stop-shop from enquiry through to ticket purchase. Already over 60,000 Virgin Trains customers have bought tickets through the new improved website. Searching for, and identifying, the cheapest available tickets for a rail journey has long been a bone of contention for many passengers. However, Virgin Trains has tackled this issue head on by developing and implementing a brand new search engine which simplifies the process and enables passengers to identify and purchase the best rail fare available quickly. While the railways are moving towards simplification of advance purchase fares across the industry, Virgin Trains is leading the way with its new, improved search engine (www.virgintrains.com) which has been developed in conjunction with ticket retailer The Trainline.com. Virgin Trains is also announcing a major campaign to make rail ticket fares more transparent and raise awareness of the value for money of rail travel. The new search engine and simpler, more user-friendly website will present rail passengers with the cheapest advance purchase – or walk-up – fares which are available for their chosen journey. No longer are all fares shown, irrespective of whether they are available or not. In a separate development, passengers who are unable to buy a Virgin Advance ticket for both the outward and return legs of their journey, or unable to specify an exact train for one leg of a return journey, are now able to mix and match ticket types and buy a Saver Half Return (at half the price of a Saver Return) for either the outward or return leg of the journey. -

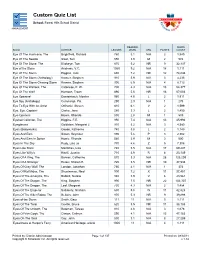

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Forest Hills School District MANAGEMENT READING WORD BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® LEVEL GRL POINTS COUNT Eye Of The Hurricane, The Brightfield, Richard 760 5.1 N/A 2 1,549 Eye Of The Needle Sloat, Teri 550 3.9 M 2 974 Eye Of The Stone, The Birdseye, Tom 670 5.2 NR 9 32,337 Eye of the Storm Andrews, V.C. 1060 9.2 N/A 18 1,111 Eye Of The Storm Higgins, Jack 680 7.2 NR 12 74,846 Eye Of The Storm (Anthology) Kramer, Stephen 910 5.9 N/A 3 4,235 Eye Of The Storm-Chasing Storm Kramer, Stephen 990 6.5 N/A 4 8,113 Eye Of The Warlock, The Catanese, P. W. 700 4.3 N/A 13 54,377 Eye Of The Wolf Harrison, Troon 890 5.6 NR 16 67,003 Eye Openers! Dossenbach, Monika 960 4.6 L 2 1,911 Eye Spy (Anthology) Cummings, Pat 290 2.3 N/A 1 275 Eye To Eye With An Artist Otfinoski, Steven 810 6.1 V 2 1,599 Eye, Eye, Captain! Clarke, Jane 580 3.3 L 2 1,450 Eye-Openers Howie, Rhonda 530 2.8 M 1 589 Eyeball Collector, The Higgins, F.E. 950 7.4 N/A 13 45,994 Eyeglasses Goldstein, Margaret J. 910 5.2 N/A 3 4,580 Eyes (Bodyworks) Goode, Katherine 740 3.8 L 2 1,149 Eyes And Ears Simon, Seymour 890 5.6 P 3 2,302 Eyes And Ears In Space Howie, Rhonda 560 2.9 M 3 500 Eyes In The Sky Rudy, Lisa Jo 770 4.6 Z 5 7,308 Eyes Like Stars Mantchev, Lisa 740 5.5 N/A 17 69,247 Eyes Like Willy's Havill, Juanita 710 3.9 R 8 23,149 Eyes Of A King, The Banner, Catherine 570 3.3 N/A 28 125,209 Eyes Of A Stranger Heisel, Sharon E. -

RNCM-Brochure-Summer-19-Web.Pdf

FS original What makes something original? Does originality actually exist or do we ԥ O UܼGݤܼQޖܥԥ O UܼGݤܼQޖԥ all simply build from what we have seen adjective and heard? adjective: original 1. What enables us to dare to be different not dependent on other people's ideas; inventive or novel. from others or independent of the context "a subtle and original thinker" in which we are working? What does the future of music look like? www.rncm.ac.uk/soundsoriginal 2 3 Wed 24 Apr // 7.30pm // RNCM Concert Hall TRINITY CHURCH OF ENGLAND HIGH SCHOOL ANNIVERSARY CONCERT 2019 TWO FOR TUBULAR BELLS Tickets £5 Promoted by Trinity Church of England High School Sun 28 Apr // 7pm // RNCM Concert Hall OLDHAM CHORAL SOCIETY VERDI REQUIEM East Lancs Sinfonia Linda Richardson soprano Kathleen Wilkinson mezzo-soprano David Butt Philip tenor Thomas D Hopkinson bass Thu 02 – Sat 04 May // 7.30pm Nigel P Wilkinson conductor Sat 04 May // 2pm // RNCM Theatre Tickets £15 Promoted by Oldham Choral Society RNCM YOUNG COMPANY SWEET CHARITY Photo credit: Warren Kirby Mon 29 Apr // 7.30pm Book by Neil Simon // Carole Nash Recital Room Music by Cy Coleman Mon 29 Apr // 7.30pm // RNCM Concert Hall Lyrics by Dorothy Fields ROSAMOND PRIZE Based on an original screenplay by Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli and Ennio Flaino TUBULAR BELLS FOR Produced for the Broadway stage by Fryer, Carr and Harris Conceived, Staged and Choreographed by Bob Fosse RNCM student composers collaborate with TWO Joseph Houston director Creative Writing students from Manchester Madeleine Healey associate director Metropolitan University to create new George Strickland musical director works in this annual prize. -

Case Fifteen

AGFC15 16/12/2004 17:16 Page 120 case fifteen Richard Branson and the Virgin Group of Companies in 2004 TEACHING NOTE SYNOPSIS By 2004, Richard Branson’s business empire extended from airlines and railways to financial services and mobile telephone services. There was little evidence of any slow- ing up of the pace of new business startups. In the first 4 years of the new century, Virgin had founded a new airline in Australia; retail ventures in Singapore and Thailand; wireless telecom companies in Asia, the US, and Australia; and a wide variety of online retailing. While several of these new ventures had been very successful (the Australian airline Virgin Blue and Virgin Mobile in particular), the financial health of several other Virgin companies was looking precarious. Several of Branson’s startups had been financial disasters – Virgin Cola and Victory Corporation in par- ticular. Other more established members of the Virgin group (such as Virgin Rail and Virgin Atlantic) required substantial investment, while yielding disappointing operating earnings. While Branson’s enthusiasm for supporting new business ideas and launching companies that would challenge business orthodoxy and seek new approaches to meeting customer needs seemed to be undiminished, skeptics sug- gested that the Virgin brand had become overextended and that Branson was losing his golden touch. The case outlines the development of the Virgin group of companies from Branson’s first business venture and offers insight into the nature of Branson’s leadership, the This note was prepared by Robert M. Grant. 120 AGFC15 16/12/2004 17:16 Page 121 RICHARD BRANSON AND THE VIRGIN GROUP OF COMPANIES IN 2004 121 management principles upon which the Virgin companies are launched and operated, and the way in which the group is run.