Music After 9/11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ratner Kills Mr

Brooklyn’s Real Newspaper BrooklynPaper.com • (718) 834–9350 • Brooklyn, NY • ©2008 BROOKLYN HEIGHTS–DOWNTOWN–NORTH BROOKLYN AWP/18 pages • Vol. 31, No. 8/9 • Feb. 23/March 1, 2008 • FREE INCLUDING CARROLL GARDENS, COBBLE HILL, BOERUM HILL, DUMBO, WILLIAMSBURG AND GREENPOINT RATNER KILLS MR. BROOKLYN By Gersh Kuntzman EXCLUSIVE right now,” said Yassky (D– The Brooklyn Paper Brooklyn Heights). “Look, a lot of developers are re-evalut- Developer Bruce Ratner costs had escalated and the num- ing their numbers and feel that has pulled out of a deal with bers showed that we should residential buildings don’t City Tech that could have net not go down that road,” added work right now,” he said. him hundreds of millions of the executive, who did not wish Yassky called Ratner’s dollars and allowed him to to be identified. withdrawal “good news” for build the city’s tallest resi- Costs had indeed escalated. Brooklyn. dential tower, the so-called In 2005, CUNY agreed to pay “A residential building at Mr. Brooklyn, The Brooklyn Ratner $86 million to build the that corner was an awkward Paper has learned. 11- to 14-story classroom-dor- fit,” said Yassky. “A lot of plan- “It was a mutual decision,” mitory and also to hand over ners see that site as ideal for a said a key executive at the City the lucrative development site significant office building.” University of New York, which where City Tech’s Klitgord Forest City Ratner did not would have paid Ratner $300 Auditorium now sits. return two messages from The million to build a new dorm Then in December, CUNY Brooklyn Paper. -

Flying Man and Falling Man: Remembering and Forgetting 9/11 Graley Herren Xavier University - Cincinnati

Xavier University Exhibit Faculty Scholarship English 2014 Flying Man and Falling Man: Remembering and Forgetting 9/11 Graley Herren Xavier University - Cincinnati Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/english_faculty Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Herren, Graley, "Flying Man and Falling Man: Remembering and Forgetting 9/11" (2014). Faculty Scholarship. Paper 3. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/english_faculty/3 This Book Chapter/Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 9 Flying Man and Falling Man Remembering and Forgetting 9 /11 Graley Herren More than a decade after the September 11 attacks, Ame~cans continue struggling to assimilate what happened on that day. This chapter consi ders how key icons, performances, and spectacles have intersected with narrative reconstructions to mediate collective memories of 9/11, within New York City, throughout the United States, and around the globe. In Cloning Tenvr: The War of Images, 9/11 to the Present, W. J. T. Mitchell starts from this sound historiographical premise: "Every history is really two histories. There is the history of what actually happened, and there is the history of the perception of what happened. The first kind of history focuses on the facts and figures; the second concentrates on the images and words that define the framework within which those facts and figures make sense" (xi). What follows is an examination of that second kind of history: the perceptual frameworks for making sense of 9/11, frameworks forged by New Yorkers at Ground Zero, Americans removed from the attacks, and cultural creators and commentators from abroad. -

Man on Wire Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com Man on Wire Discussion Guide Director: James Marsh Year: 2008 Time: 94 min You might know this director from: Project Nim (2011) Shadow Dancer (2012) The King (2005) FILM SUMMARY MAN ON WIRE is the story of French tightrope walker Philippe Petit who, on August 7, 1974, broke into the newly constructed Twin Towers of Manhattan. After months of painstaking preparations, he managed to enter the buildings during the night and string a wire between the two towers. For the next 45 minutes, Philippe Petit walked, danced, kneeled, and laid down on the wire - an expeirence he had dreamt of ever since he read about the Twin Towers six years before. Using contemporary interviews, archival footage, and Philippe’s own creations, this film tells the story of Philippe’s previous walks between towers such as the Notre Dame and the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Viewers learn about his passions, his friendships, and how he accomplished his Twin Towers walk, from getting the wire into the towers and hiding from guards to mounting the wire and taking the first step. The result is a story of daring, beauty, dedication to the point of insanity, loyalty and heartbreak, and the firm belief that nothing is impossible. Discussion Guide Man on Wire 1 www.influencefilmclub.com FILM THEMES On the surface, MAN ON WIRE may appear to be about one man’s determination to achieve his dream, but the story reveals a lot about human nature, from friendship and loyalty to dreaming beyond the norm “I must be a and achieving the impossible. -

West Allis Players Capture Spirit of Neil Simon's

16 • Milwaukee County Post • October 9, 2015 THIS 6TH & ENTERTAINMENT SATURDAY HOWARD AT THE OPEN 1PM-5PM West Allis Players capture spirit of THIS WEEK AT THE GARDEN DISTRICT FARMERS’ MARKET What’s Fresh This Week Neil Simon’s ‘Barefoot in the Park’ Time to can the applesauce! The veggies are still plentiful from beets, beans, Brussels Cast adeptly At a glance sprouts, cabbage, carrots, chard, cucum- bers, garlic, kale, kohlrabi, pattypan, pota- captures trials “Barefoot in the Park” The curtain goes up at 7:30 p.m. Friday and toes, peppers, tomatillos, kohlrabi, onions, of newlyweds Saturday and 2 p.m. Sunday at West Allis Central squash, watermelons and more! We’re also Auditorium.Visit www.westallisplayers.org. joined this week by Clock Shadow By JULIE MCHALE Creamery, Custom Grown Greenhouse, Post Theater Critic is adjusting to her new single status, and Elsen Orchard, Golden Eggroll, Log Cabin Corie is trying to encourage her to take a Orchard, Magpie’s Gourmet Dog Treats, WEST ALLIS — It is no surprise that few risks and create a new life for herself. Soap of the Earth, and amazing flowers. Neil Simon’s 1963 play “Barefoot in the Two other characters arrive upon the Follow us on Facebook for updates Park” continues its popularity. Simon’s scene — a telephone repairman and a longest-running Broadway show still slightly eccentric, interfering moocher Our Sponsors Help Make the amuses us because of its recognizable situ- named Velasco, the neighbor who lives in Market Possible ations, its accessible characters and its the attic above the Bratters. -

The Width of Infinity Is a House Squatting on an Unnamed Street

THE WIDTH OF INFINITY IS A HOUSE SQUATTING ON AN UNNAMED STREET A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the DeGree Master of Fine Arts Joel Lee May, 2011 THE WIDTH OF INFINITY IS A HOUSE SQUATTING ON AN UNNAMED STREET Joel Lee Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Mary Biddinger Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Michael Dumanis Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Department Chair Mr. David Giffels Dr. Michael Schuldiner _______________________________ Date ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTERRUPTING THE MEETING OF HUMAN DEFINITION AND BIBLICAL PROPORTIONS……………………………………………………………………………………………………...1 THE FEAR OF BEING LEFT ALONE………………………………………………………………………..2 A SHORT AUTOBIOGRAPHY, WITH LOVE……………………………………………………………...4 SAVE THE TRAUMA FOR YOUR MAMA………………………………………………………………….5 THE DISPERSAL PATTERN OF RECENTLY TRAFFICJAMMED VEHICLES………………...6 HOLY FUCKING SHIT, WORDS ARE STILL WORDS EVEN AFTER THE ALPHABET RETIRED……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...8 SOMEBODY IS PROBABLY STILL ALIVE SOMEWHERE, EVEN IF THERE IS NOTHING LEFT………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….10 WHEN YOU’VE BECOME YOUR FATHER, THAT’S WHEN YOU EMBRACE EUTHANASIA……………………………………………………………………………………………………..12 AND THIS IS WHERE YOU PICK UP THE MACHINE GUN………………………………………14 -

Art, Memory, and Historical Reclamation in Colum Mccann's Let the Great World Spin

This is a repository copy of "Anticipating the Fall": Art, Memory, and Historical Reclamation in Colum McCann's Let the Great World Spin. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/90682/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Carroll, HEM orcid.org/0000-0003-1177-8566 (2016) "Anticipating the Fall": Art, Memory, and Historical Reclamation in Colum McCann's Let the Great World Spin. In: Morley, C, (ed.) 9/11 Topics in Contemporary North American Literature. Bloomsbury Academic . ISBN 9781472569684 This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Bloomsbury Academic in 9/11: Topics in Contemporary North American Literature on 25 August 2016, available online: https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/911-9781472569684/ Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the -

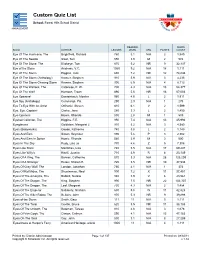

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Forest Hills School District MANAGEMENT READING WORD BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® LEVEL GRL POINTS COUNT Eye Of The Hurricane, The Brightfield, Richard 760 5.1 N/A 2 1,549 Eye Of The Needle Sloat, Teri 550 3.9 M 2 974 Eye Of The Stone, The Birdseye, Tom 670 5.2 NR 9 32,337 Eye of the Storm Andrews, V.C. 1060 9.2 N/A 18 1,111 Eye Of The Storm Higgins, Jack 680 7.2 NR 12 74,846 Eye Of The Storm (Anthology) Kramer, Stephen 910 5.9 N/A 3 4,235 Eye Of The Storm-Chasing Storm Kramer, Stephen 990 6.5 N/A 4 8,113 Eye Of The Warlock, The Catanese, P. W. 700 4.3 N/A 13 54,377 Eye Of The Wolf Harrison, Troon 890 5.6 NR 16 67,003 Eye Openers! Dossenbach, Monika 960 4.6 L 2 1,911 Eye Spy (Anthology) Cummings, Pat 290 2.3 N/A 1 275 Eye To Eye With An Artist Otfinoski, Steven 810 6.1 V 2 1,599 Eye, Eye, Captain! Clarke, Jane 580 3.3 L 2 1,450 Eye-Openers Howie, Rhonda 530 2.8 M 1 589 Eyeball Collector, The Higgins, F.E. 950 7.4 N/A 13 45,994 Eyeglasses Goldstein, Margaret J. 910 5.2 N/A 3 4,580 Eyes (Bodyworks) Goode, Katherine 740 3.8 L 2 1,149 Eyes And Ears Simon, Seymour 890 5.6 P 3 2,302 Eyes And Ears In Space Howie, Rhonda 560 2.9 M 3 500 Eyes In The Sky Rudy, Lisa Jo 770 4.6 Z 5 7,308 Eyes Like Stars Mantchev, Lisa 740 5.5 N/A 17 69,247 Eyes Like Willy's Havill, Juanita 710 3.9 R 8 23,149 Eyes Of A King, The Banner, Catherine 570 3.3 N/A 28 125,209 Eyes Of A Stranger Heisel, Sharon E. -

RNCM-Brochure-Summer-19-Web.Pdf

FS original What makes something original? Does originality actually exist or do we ԥ O UܼGݤܼQޖܥԥ O UܼGݤܼQޖԥ all simply build from what we have seen adjective and heard? adjective: original 1. What enables us to dare to be different not dependent on other people's ideas; inventive or novel. from others or independent of the context "a subtle and original thinker" in which we are working? What does the future of music look like? www.rncm.ac.uk/soundsoriginal 2 3 Wed 24 Apr // 7.30pm // RNCM Concert Hall TRINITY CHURCH OF ENGLAND HIGH SCHOOL ANNIVERSARY CONCERT 2019 TWO FOR TUBULAR BELLS Tickets £5 Promoted by Trinity Church of England High School Sun 28 Apr // 7pm // RNCM Concert Hall OLDHAM CHORAL SOCIETY VERDI REQUIEM East Lancs Sinfonia Linda Richardson soprano Kathleen Wilkinson mezzo-soprano David Butt Philip tenor Thomas D Hopkinson bass Thu 02 – Sat 04 May // 7.30pm Nigel P Wilkinson conductor Sat 04 May // 2pm // RNCM Theatre Tickets £15 Promoted by Oldham Choral Society RNCM YOUNG COMPANY SWEET CHARITY Photo credit: Warren Kirby Mon 29 Apr // 7.30pm Book by Neil Simon // Carole Nash Recital Room Music by Cy Coleman Mon 29 Apr // 7.30pm // RNCM Concert Hall Lyrics by Dorothy Fields ROSAMOND PRIZE Based on an original screenplay by Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli and Ennio Flaino TUBULAR BELLS FOR Produced for the Broadway stage by Fryer, Carr and Harris Conceived, Staged and Choreographed by Bob Fosse RNCM student composers collaborate with TWO Joseph Houston director Creative Writing students from Manchester Madeleine Healey associate director Metropolitan University to create new George Strickland musical director works in this annual prize. -

Downbeat.Com July 2015 U.K. £4.00

JULY 2015 2015 JULY U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT ANTONIO SANCHEZ • KIRK WHALUM • JOHN PATITUCCI • HAROLD MABERN JULY 2015 JULY 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

The Politico-Aesthetics of Groundlessness and Philippe Petit’S High-Wire Walk

ARTICLES The Politico-Aesthetics of Groundlessness and Philippe Petit’s High-Wire Walk Gwyneth Shanks When I see two oranges, I juggle; when I see two towers, I walk. —Philippe Petit, To Reach the Clouds A figure stands in open air. Centred in the photo, the body seems suspended in the expanse of hazy, blue sky that opens up around their small form. On the right-hand side of the image, one tower of the newly built World Trade Center (WTC) looms. The figure is small in comparison, a smudge of black made insubstantial next to the clean, geometric grid of the tower’s detailed façade. And yet it is the figure that arrests the viewer’s gaze. The ground upon which this person stands is nothing but a thin cable, barely visible in the photograph. The photo, taken the morning of August 7, 1974, is of French high-wire walker Philippe Petit. Captured by Petit’s friend and co-conspirator, Jean-Louis Blondeau, the image reveals a figure caught between ground and sky, between the two towers of the WTC, and between life and death. Suspended between the Twin Towers, balanced on his wire, Petit’s walk celebrates the precarity of groundlessness. Philippe Petit on a cable suspended between the two towers of the newly completed World Trade Center in New York City, August 7, 1974. Film still from the 2008 documentary, Man on Wire, directed by James Marsh. Photo: Jean-Louis Blondeau, 1974. ____________________________________________________________________________________ Gwyneth Shanks is the Interdisiplinary Art Fellow at the Walker Art Center. She holds a PhD in Theater and Performance Studies from University of California, Los Angeles and an MA in Performance Studies from New York University. -

Azzschool at CALIFORNIA JAZZ CONSERVATORY

the azzschool at CALIFORNIA JAZZ CONSERVATORY 2019 SPRING CATALOG CLASSES • WORKSHOPS • CONCERTS Contents “The most successful INTRODUCTION ADULT VOCAL CLASSES (continued) jazz education startup CJC Concert Series 2 Composition/Songwriting 28 The California Jazz Conservatory 4 Young Singers 28 The Jazzschool 6 Vocal Mentor Program 29 Vocal Workshops 30 in the United States” ADULT PERFORMANCE ENSEMBLES YOUNG MUSICIANS PROGRAM — Ted Gioia Jazz 8 World 12 Introduction 32 Latin 12 Program Requirements 32 Thank you, jazz historian Brazilian 13 Placement and Audition Ted Gioia, for recognizing the Blues 13 Requirements 33 California Jazz Conservatory Funk 13 Instrumental Ensembles 34 and our 20+ years of success Voice 35 ADULT INSTRUMENTAL CLASSES in teaching people how WORKSHOPS Piano and Keyboards 14 to play, study and Guitar 16 Workshops 36 enjoy jazz. Saxophone 1 9 Percussion Series 40 Bass 1 9 Raul Midón / Lionel Loueke Drums and Percussion 20 Workshop 46 THEORY, IMPROVISATION, SUMMER PREVIEW COMPOSITION Introduction 47 Theory 21 Summer Youth Program 48 Harmony 21 High School Jazz Intensive 49 Improvisation 22 Girls’ Jazz & Blues Camp 50 Composition 22 Theo Bleckmann / Laurie Antonioli Vocal Intensive 51 ADULT VOCAL CLASSES Jazz Guitar Intensive 52 Vocal Technique 23 Jazz Piano Intensive 53 Performance 23 INFORMATION Jazz 23 R&B/Pop/Latin 25 Jazzschool Faculty 54 Vocal Ensembles 26 Board and Staff 60 Salsa Singing 26 Instructions and Funk 26 Application Form 62 World Groove 27 Map 63 Blues and Groove 27 Support 64 Brazilian 27 IMPORTANT INFORMATION • The Jazzschool Spring Quarter runs from April 8 – June 10. • Spring Performance Series takes place June 11 – 17. -

Images of Falling Through 9/11 and Beyond

FALLING THROUGH THE MESHWORK: IMAGES OF FALLING THROUGH 9/11 AND BEYOND by REBECCA CLAIRE JUSTICE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY American and Canadian Studies Centre School of English, Drama, American & Canadian Studies College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham December 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis considers images of the falling body after the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, starting with Associated Press photographer Richard Drew’s photograph of a person falling to their death from the north tower of the World Trade Center. From this specific photograph, this thesis follows various intersecting lines in what I am calling a meshwork of falling-body images. Consequently, each chapter encounters a wide range of examples of falling: from literature to films, personal websites to digital content and immersive technologies to art works. Rather than connecting these instances like nodes, this thesis is more concerned with exploring lines of relation and the way the image moves along these lines.