LEFT to DIE Produced, Written & Directed by Kenneth A. Simon Www

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brothers in Arms 1945 March 12-18

1 Brothers in Arms 1945 March 12-18 In the 1998 Hollywood drama Saving Private Ryan, Tom Hanks portrays an officer leading a squad of U.S. Army Rangers behind German lines shortly after the Normandy invasion. Their mission is to find a paratrooper, Private James Ryan played by Matt Damon, and bring him back to safety because his three brothers have been killed in action. General George C. Marshall personally ordered the mission to save the life of an Iowa family's sole surviving son. There was no Private Ryan in this situation during World War II, but the scenario is based in fact. The danger of brothers serving together on the same ship was demonstrated on the first day of World War II for the United States. Thirty-eight sets of brothers (79 individuals) were serving on board the battleship U.S. S. Arizona when Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese. When a Japanese bomb penetrated the forward ammunition magazine of the Arizona, sixty-three brothers (23 sets) died in the massive explosion that sank the ship. Of the three sets of three brothers on the ship, only one individual of each set survived. The only set of brothers who remained intact after the attack on the Arizona were Kenneth Warriner, who was on temporary assignment in San Diego, and Russell Warriner, who was badly burned.1 The devastation of Pearl Harbor would also be linked another family tragedy involving brothers. A sailor from Fredericksburg, Iowa named William Ball was one of the thousands of Americans killed in the attack. -

164Th Infantry News: September 1998

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons 164th Infantry Regiment Publications 9-1998 164th Infantry News: September 1998 164th Infantry Association Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/infantry-documents Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation 164th Infantry Association, "164th Infantry News: September 1998" (1998). 164th Infantry Regiment Publications. 55. https://commons.und.edu/infantry-documents/55 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in 164th Infantry Regiment Publications by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE 164TH INFANTRY NEWS Vot 38 · N o, 6 Sepitemlber 1, 1998 Guadalcanal (Excerpts taken from the book Orchids In The Mud: Edited by Robert C. Muehrcke) Orch id s In The Mud, the record of the 132nd Infan try Regiment, edited by Robert C. Mueherke. GUADALCANAL AND T H E SOLOMON ISLANDS The Solomon Archipelago named after the King of Kings, lie in the Pacific Ocean between longitude 154 and 163 east, and between latitude 5 and 12 south. It is due east of Papua, New Guinea, northeast of Australia and northwest of the tri angle formed by Fiji, New Caledonia, and the New Hebrides. The Solomon Islands are a parallel chain of coral capped isles extending for 600 miles. Each row of islands is separated from the other by a wide, long passage named in World War II "The Slot." Geologically these islands are described as old coral deposits lying on an underwater mountain range, whi ch was th rust above the surface by long past volcanic actions. -

Sullivan Brothers Deaths Changed How US Manned Military Units

Sullivan Brothers Deaths Changed How US Manned Military Units 3.6K The five brothers on board the light cruiser Juneau (left), Joseph, Francis, Albert, Madison and George Sullivan were five siblings who all died during the same attack in World War II during the Battle of Guadalcanal, November 1942. In the late evening and early morning of Nov. 12-13, 1942, the United States and Japan engaged in one of the most brutal naval battles of World War II. Minutes into the fight, north of Guadalcanal, a torpedo from Japanese destroyer Amatsukaze ripped into the port side of the American light cruiser Juneau (CL-52), taking out its steering and guns and killing 19 men in the forward engine room. The keel buckled and the propellers jammed. During the 10-15 minutes the crew was engaged in battle, sailors vomited and wept; to hide from the barrage, others tried to claw their way into the steel belly of their vessel. The ship listed to port, with its bow low in the water, and the stink of fuel made it difficult to breathe below deck. The crippled Juneau withdrew from the fighting, later that morning joining a group of five surviving warships from the task force as they crawled toward the comparative safety of the Allied harbor at Espiritu Santo, in the New Hebrides. Fumes continued to foul the air in the holds; many of the ship’s original complement of 697 sailors — which included five brothers from Waterloo, Iowa — were crowded together topside, blistered from the sun. At 11:01 a.m., the Japanese submarine I-26 tracking the vessels fired another torpedo into the already off-kilter Juneau. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Download the Full Article As Pdf ⬇︎

wreck rap Text and photos by Vic Verlinden The armored cruiser Friedrich Carl was constructed in the year 1902 at the well-known shipyard of Blohm & Voss in Hamburg, Germany. The armored cruis- er had a length of 126m and was equipped with an impres- sive array of guns and torpedo launchers. She was the second ship of the Prinz Adalbert class when she was commissioned by the Imperial German Navy on the 12 December 1903. SMS Friedrich Carl — Diving the Flagship of Admiral Ehler Behring In the early years, she served as a tor- ship of Rear Admiral Ehler Behring. At this At the start of the war, Behring was eral light cruisers and four destroyers. The pedo training ship. Because of her three time, she was converted to carry two ordered to actively monitor the activities squadron was operating from the port engines, she could reach a top speed seaplanes. She was the first ship of the and movements of the Russian fleet in of Danzig but was not able to sail due to of 20 knots. During the outbreak of the Imperial Navy able to carry and launch the Baltic Sea. To execute this mission, the the bad weather. First World War, she served as the flag- seaplanes. Friedrich Carl was accompanied by sev- Historical photo of SMS Friedrich Carl 15 X-RAY MAG : 90 : 2019 EDITORIAL FEATURES TRAVEL NEWS WRECKS EQUIPMENT BOOKS SCIENCE & ECOLOGY TECH EDUCATION PROFILES PHOTO & VIDEO PORTFOLIO Canon (left and bottom right) on the wreck of the Friedrich wreck Carl; Discaarded fishing nets rap cover parts of the wreck (below) What are you waiting for? Visit Grand Cayman for it’s spectacular drop offs An unexpected explosion the beautiful warship was a heavy Despite the bad weather, the blow to the German navy, as Russian minelayers had not been the vessel could not be replaced idle and had laid various mine- immediately. -

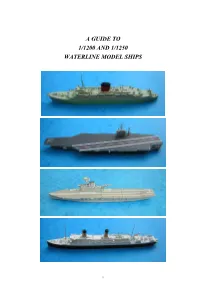

Model Ship Book 4Th Issue

A GUIDE TO 1/1200 AND 1/1250 WATERLINE MODEL SHIPS i CONTENTS FOREWARD TO THE 5TH ISSUE 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 2 Aim and Acknowledgements 2 The UK Scene 2 Overseas 3 Collecting 3 Sources of Information 4 Camouflage 4 List of Manufacturers 5 CHAPTER 2 UNITED KINGDOM MANUFACTURERS 7 BASSETT-LOWKE 7 BROADWATER 7 CAP AERO 7 CLEARWATER 7 CLYDESIDE 7 COASTLINES 8 CONNOLLY 8 CRUISE LINE MODELS 9 DEEP “C”/ATHELSTAN 9 ENSIGN 9 FIGUREHEAD 9 FLEETLINE 9 GORKY 10 GWYLAN 10 HORNBY MINIC (ROVEX) 11 LEICESTER MICROMODELS 11 LEN JORDAN MODELS 11 MB MODELS 12 MARINE ARTISTS MODELS 12 MOUNTFORD METAL MINIATURES 12 NAVWAR 13 NELSON 13 NEMINE/LLYN 13 OCEANIC 13 PEDESTAL 14 SANTA ROSA SHIPS 14 SEA-VEE 16 SANVAN 17 SKYTREX/MERCATOR 17 Mercator (and Atlantic) 19 SOLENT 21 TRIANG 21 TRIANG MINIC SHIPS LIMITED 22 ii WASS-LINE 24 WMS (Wirral Miniature Ships) 24 CHAPTER 3 CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURERS 26 Major Manufacturers 26 ALBATROS 26 ARGONAUT 27 RN Models in the Original Series 27 RN Models in the Current Series 27 USN Models in the Current Series 27 ARGOS 28 CM 28 DELPHIN 30 “G” (the models of Georg Grzybowski) 31 HAI 32 HANSA 33 NAVIS/NEPTUN (and Copy) 34 NAVIS WARSHIPS 34 Austro-Hungarian Navy 34 Brazilian Navy 34 Royal Navy 34 French Navy 35 Italian Navy 35 Imperial Japanese Navy 35 Imperial German Navy (& Reichmarine) 35 Russian Navy 36 Swedish Navy 36 United States Navy 36 NEPTUN 37 German Navy (Kriegsmarine) 37 British Royal Navy 37 Imperial Japanese Navy 38 United States Navy 38 French, Italian and Soviet Navies 38 Aircraft Models 38 Checklist – RN & -

World War Ii Veteran’S Committee, Washington, Dc Under a Generous Grant from the Dodge Jones Foundation 2

W WORLD WWAR IIII A TEACHING LESSON PLAN AND TOOL DESIGNED TO PRESERVE AND DOCUMENT THE WORLD’S GREATEST CONFLICT PREPARED BY THE WORLD WAR II VETERAN’S COMMITTEE, WASHINGTON, DC UNDER A GENEROUS GRANT FROM THE DODGE JONES FOUNDATION 2 INDEX Preface Organization of the World War II Veterans Committee . Tab 1 Educational Standards . Tab 2 National Council for History Standards State of Virginia Standards of Learning Primary Sources Overview . Tab 3 Background Background to European History . Tab 4 Instructors Overview . Tab 5 Pre – 1939 The War 1939 – 1945 Post War 1945 Chronology of World War II . Tab 6 Lesson Plans (Core Curriculum) Lesson Plan Day One: Prior to 1939 . Tab 7 Lesson Plan Day Two: 1939 – 1940 . Tab 8 Lesson Plan Day Three: 1941 – 1942 . Tab 9 Lesson Plan Day Four: 1943 – 1944 . Tab 10 Lesson Plan Day Five: 1944 – 1945 . Tab 11 Lesson Plan Day Six: 1945 . Tab 11.5 Lesson Plan Day Seven: 1945 – Post War . Tab 12 3 (Supplemental Curriculum/American Participation) Supplemental Plan Day One: American Leadership . Tab 13 Supplemental Plan Day Two: American Battlefields . Tab 14 Supplemental Plan Day Three: Unique Experiences . Tab 15 Appendixes A. Suggested Reading List . Tab 16 B. Suggested Video/DVD Sources . Tab 17 C. Suggested Internet Web Sites . Tab 18 D. Original and Primary Source Documents . Tab 19 for Supplemental Instruction United States British German E. Veterans Organizations . Tab 20 F. Military Museums in the United States . Tab 21 G. Glossary of Terms . Tab 22 H. Glossary of Code Names . Tab 23 I. World War II Veterans Questionnaire . -

The Tale of the Sullivan(S) from the Beara Peninsula

Brian P. Hegarty Jr. January 2017 The Tale of the Sullivan(s) from the Beara Peninsula When we visited Ireland in June 2016, the owner of the Bed and Breakfast where we were staying suggested we drive along the Sullivan Mile. So Amy and I did just that and the story goes like this. In 1849, Tom and Bridget Sullivan left Adrigole, Beara Peninsula, for a new life in the United States of America, where they started a family. Years later, their grandson, Tom, married a Mary Agnes Dignan. The couple settled in Waterloo, Iowa, and raised 5 sons: George, Francis, Joseph, Madison, and Albert. All five sons joined the US Navy and served on the USS Juneau during WW II. In November 1942, during the battle of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, a Japanese submarine torpedoed the ship. Many were killed, including the Sullivan brothers. Extensive newspaper and radio coverage made the family’s tragedy a national story, and Hollywood made a film The Fighting Sullivans (1944) based on a story of the brothers. In consequence of the suffering brought to the family by a single event, the US Navy altered its policy, prohibiting brothers from serving in action together. The five brothers were posthumously awarded the Purple Heart Medal, and a United States naval destroyer was commissioned in 1943 and named USS The Sullivans in their memory. A replacement USS The Sullivans was launched in 1995 by Kelly Longhren Sullivan, granddaughter of Albert and the ship anchored off the Beara peninsula. Commemorative plaques were unveiled in Adrigola, near the site of the original family home. -

Uss Juneau Remembrance Day November 13, 2013

Office of The Mayor City & Borough of Juneau, Alaska PROCLAMATION USS JUNEAU MEMORIAL CENTER WHEREAS, The USS Juneau (CL52) was a light cruiser LAUNCHED IN October 1941 by the U.S. Navy; at the Federal Shipyard and Dry-dock Company in the town of Kearny, the County of Hudson, New Jersey; and WHEREAS, The USS J11l1eaUwas named in honor of the City of Juneau, the Capital of the Territory of Alaska, now the City and Borough of Juneau, the Capital of the State of Alaska; and WHEREAS, On November 13,1942 at the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, the USS Juneau was struck by two torpedoes and sank in twenty seconds with the immediate loss of nearly 600 of her crew of 700 officers and men; including the twenty crewmembers from Hudson County; and WHEREAS, After exposure, thirst, weakness due to their wounds, and shark attacks only ten sailors in the water survived; and WHEREAS, Four medical personnel also survived because they were transferred to the USS San Francisco to assist with the heavy casualties on that ship just before the USS Juneau was torpedoed; and WHEREAS, on November 13, 2013 the County of Hudson dedicates the USS Juneau Memorial Center in honor of the ship and crew. NOW THEREFORE, I, Merrill Sanford, Mayor ofthe City and Borough of Juneau, Alaska, on behalf of the City and Borough Assembly, in honor of the gallant crew of the USS Juneau who helped to secure our liberties at the cost of themselves do hereby proclaim: uss Juneau Remembrance Day November 13, 2013 IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereto set my hand and caused the seal of the City and Borough of Juneau, Alaska, to be affixed this 4thday of November, 2013.. -

Wreck of Kaga Found

Wreck of Japanese aircraft carrier sunk in Battle of Midway discovered 77 years later By James Rogers Published October 19, 2019 Fox News Researchers have discovered the wreck of the Japanese aircraft carrier Kaga 77 years after it was sunk by U.S. forces during World War II's Battle of Midway. Experts aboard the research vessel RV Petrel announced the discovery Friday. After surveying more than 500 square nautical miles, crewmembers identified the wreckage Wednesday at a depth of more than 17,000 feet in the Pacific. RV Petrel is part of Vulcan Inc., a research organization set up by the late Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen. “[The Battle of Midway] was a major carrier-to-carrier battle that left its eerie evidence strewn for thousands of miles across the ocean floor,” Robert Kraft, director of subsea operations for Vulcan, said in a statement. “With each piece of debris and each ship we discover and identify, our intent is to honor history and those who served and paid the ultimate sacrifice for their countries.” Eerie images of the Kaga captured by an undersea drone show a starboard side gun, a 20 cm gun, a gun mount and a barbette, or gun emplacement. A starboard side gun on the Kaga wreck. (Paul G. Allen’s Vulcan Inc.) The Kaga is one of four Japanese aircraft carriers that took part in the Battle of Midway, June 4-7, 1942. All four of the carriers, along with the Japanese heavy cruiser Mikuma, were sunk in the battle, marking a pivotal victory for the U.S. -

Chapter 25- United States in WWII

Warm-up for 25-1 Put yourself in the place of a high school senior in December 1941 and think about how the news of war will impact your lives. Rosie the Riveter by the Four Vagabonds When the nation entered World War II in 1941, its armed forces ranked nineteenth in might, behind the tiny European nation of Belgium. Three years later, The United States was producing 40 percent of the world’s arms. Joining the War Effort 5 million people volunteered for the war after Pearl Harbor Selective Service System drafted another 10 million George Marshall- Army Chief of Staff General; pushed for WAAC Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps- allowed for women volunteers in non-combat positions; “auxiliary” status dropped in 1943 for full benefits (army integrated men & women in 1978) African Americans, Native Americans, Mexican Americans, & Asian Americans all volunteered even though they were discriminated against “Just carve on my tombstone, ‘Here lies a black man killed fighting a yellow man for the protection of a white man.’” “To be fighting for freedom and democracy in the Far East… and to be denied equal opportunity in the greatest of democracies seems the height of irony.” Over 1 million African Americans served in segregated units, more than 300,000 Mexican Americans, more than 13,000 Chinese, 33,000 Japanese, and 25,000 Native Americans. FDR persuaded Congress to repeal the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. Production factories converted for war production auto plants produced tanks, planes, boats, & command cars shipyards used prefabricated parts that could be quickly assembled 6 out of 18 million new workers were women women operated welding torches & riveting guns just as well as men but earned 60 percent as much as men doing the same jobs Hull 440 was the famous Liberty Ship, the Robert E Peary. -

Model Ship Book 9Th Issue

in 1/1200 & 1/1250 scale Issue 11 (April 2017) How it all began CONTENTS FOREWORD 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 3 Aim and Acknowledgements 3 The UK Scene 3 Overseas 5 Collecting 5 Sources of Information 5 Warship Camouflage 6 Lists of Manufacturers 6 CHAPTER 2 UNITED KINGDOM MANUFACTURERS 9 ATLAS EDITIONS 9 BASSETT-LOWKE 9 BROADWATER 10 CAP AERO 10 CLYDESIDE 10 COASTLINES 11 CONNOLLY 11 CRUISE LINE MODELS 12 DC MARINE MODELS 12 DEEP ‘C’/ATHELSTAN 12 ENSIGN 12 FERRY SMALL SHIPS 13 FIGUREHEAD 13 FLEETLINE 13 GORKY 14 GRAND FLEET MINIATURES 14 GWYLAN 14 HORNBY MINIC (ROVEX) 15 KS MODELSHIPS 15 LANGTON MINIATURES 15 LEICESTER MICROMODELS 16 LEN JORDAN MODELS 16 LIMITED EDITIONS 16 LLYN 17 LOFTLINES 17 MARINE ARTISTS MODELS 18 MB/HIGHWORTH MODELS 18 MOUNTFORD MODELS 18 NAVWAR 19 NELSON 20 NKC SHIPS 20 OCEANIC 20 PEDESTAL 21 PIER HEAD MODELS 21 SANTA ROSA SHIPS 21 SEA-VEE 23 SKYTREX/MERCATOR (TRITON 1250) 25 Mercator (and Atlantic) 28 SOLENT MODEL SHIPS 31 TRIANG 31 TRIANG MINIC SHIPS LIMITED 33 (i) WASS-LINE 34 WMS (Wirral Miniature Ships) 35 CHAPTER 3 CONTINENTAL MANUFACTURERS 36 Major Manufacturers 36 ALBATROS 36 ARGONAUT 36 RN Models in the Original Series 37 USN Models in the Original Series 38 ARGOS 38 CARAT & CSC 39 CM 40 DELPHIN 43 ‘G’ (the models of Georg Grzybowski) 45 HAI 47 HANSA 49 KLABAUTERMANN 52 NAVIS/NEPTUN (and Copy) 53 NAVIS WARSHIPS 53 Austro-Hungarian Navy 53 Brazilian Navy 54 Royal Navy 54 French Navy 54 Italian Navy 54 Imperial Japanese Navy 55 Imperial German Navy (& Reichmarine) 55 Russian Navy 55 Swedish Navy 55 United