Corn Smuts S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biology and Histopathology of Ustilago Filiformis (= U. Longissima), a Causal Agent of Leaf Stripe Smut of Glyceria Multiflora

JOURNAL OF PLANT PROTECTION RESEARCH Vol. 55, No. 4 (2015) DOI: 10.1515/jppr-2015-0059 Biology and histopathology of Ustilago filiformis (=U. longissima), a causal agent of leaf stripe smut of Glyceria multiflora Analía Perelló1*, Marta Mónica Astiz Gasso2, Marcelo Lovisolo3 1 Technologist Institute Santa Catalina (IFSC), 1836 Llavallol, Faculty of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences, National University of La Plata, Street 60 and 119, Buenos Aires, Argentina 2 Faculty of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences, National University of La Plata, Street 60 and 119, Buenos Aires, Argentina 3 Chair of Botany, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, National University of Lomas de Zamora, 1832 Lomas de Zamora, Buenos Aires, Argentina Received: March 16, 2015 Accepted: November 12, 2015 Abstract: The aims of this study were to clarify the reproductive biology of the Ustilago filiformis Schrank, as causal agent of the stripe smut of Glyceria multiflora, determine the infection process of the pathogen and analyze the histological changes associated host- Glyceria any fungus attack. Moreover, the life cycle of the fungus was elucidated for the first time. Both teliospores and basidiospores were found to be equally efficient in producing the infection in Glyceria plants after the plants had been inoculated. These results constitute an important contribution for the understanding of the epidemiology of the disease. Key words: basidiospores, infection cycle, stripe smut, teliospores Introduction dia, the USSR (Siberia); Europe – Austria, Bulgaria, Czech, Smut fungi are Basidiomycota fungi belonging to the Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Po- order Ustilaginales. They received this name due to the land, Romania, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United very conspicuous symptoms of black teliospore masses Kingdom, the former Yugoslavia; and North and South resembling smut, which they often produce on the host America. -

![Rice False Smut [Ustilaginoidea Virens (Cooke) Takah.] in Paraguay](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4603/rice-false-smut-ustilaginoidea-virens-cooke-takah-in-paraguay-334603.webp)

Rice False Smut [Ustilaginoidea Virens (Cooke) Takah.] in Paraguay

ISSN (E): 2349 – 1183 ISSN (P): 2349 – 9265 3(3): 704–705, 2016 DOI: 10.22271/tpr.2016. v3.i3. 093 Short communication Rice false smut [Ustilaginoidea virens (Cooke) Takah.] in Paraguay Lidia Quintana1*, Susana Gutiérrez2, Marco Maidana1 and Karina Morinigo1 1Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias y Forestales, Universidad Nacional de Itapúa, Encarnación, Paraguay 2 Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias, Universidad Nacional del Nordeste, Corrientes, Argentina *Corresponding Author: [email protected] [Accepted: 28 December 2016] [Cite as: Quintana L, Gutiérrez S, Maidana M & Morinigo K (2016) Rice false smut [Ustilaginoidea virens (Cooke) Takah.] in Paraguay. Tropical Plant Research 3(3): 704–705] False smut of rice, caused by Ustilaginoidea virens (Cooke) Takah., is a common disease in rice panicles. Disease was first reported in India (1878) and was considered as a secondary disease due to their sporadic occurrence (Ladhalakshmi et al. 2012). In the 2014–2015 growing season disease survey was conducted in different rice producting areas of the country. Rice plants of IRGA 424 cultivar were observed, whose panicles had grains replaced by globose yellowish green masses of spores. These symptoms were visible after crop flowering, when the fungus transforms individual grains of the panicle into globose green-yellow mass that subsequently acquire greyish-black color. In the national bibliography no history published about this disease was found, thus the objective of this study was to determine the etiology of this new disease in Paraguay. One hundred and twenty panicles taken from fields with symptoms and signs of false smut were collected in the districts of General Delgado, General Artigas and Coronel Bogado (Itapúa Department), districts of Santa Maria, San Juan Bautista and San Juan de Ñeembucú (Misiones Department). -

Four Master Teachers Who Fostered American Turn-Of-The-(20<Sup>TH

MYCOTAXON ISSN (print) 0093-4666 (online) 2154-8889 Mycotaxon, Ltd. ©2021 January–March 2021—Volume 136, pp. 1–58 https://doi.org/10.5248/136.1 Four master teachers who fostered American turn-of-the-(20TH)-century mycology and plant pathology Ronald H. Petersen Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee Knoxville, TN 37919-1100 Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract—The Morrill Act of 1862 afforded the US states the opportunity to found state colleges with agriculture as part of their mission—the so-called “land-grant colleges.” The Hatch Act of 1887 gave the same opportunity for agricultural experiment stations as functions of the land-grant colleges, and the “third Morrill Act” (the Smith-Lever Act) of 1914 added an extension dimension to the experiment stations. Overall, the end of the 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th was a time for growing appreciation for, and growth of institutional education in the natural sciences, especially botany and its specialties, mycology, and phytopathology. This paper outlines a particular genealogy of mycologists and plant pathologists representative of this era. Professor Albert Nelson Prentiss, first of Michigan State then of Cornell, Professor William Russel Dudley of Cornell and Stanford, Professor Mason Blanchard Thomas of Wabash College, and Professor Herbert Hice Whetzel of Cornell Plant Pathology were major players in the scenario. The supporting cast, the students selected, trained, and guided by these men, was legion, a few of whom are briefly traced here. Key words—“New Botany,” European influence, agrarian roots Chapter 1. Introduction When Dr. Lexemual R. -

Corn Smuts, RPD No

report on RPD No. 203 PLANT February 1990 DEPARTMENT OF CROP SCIENCES DISEASE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN CORN SMUTS Corn smuts occur throughout the world. Common corn smut, caused by the fungus Ustilago zeae (synonym U. maydis), and head smut, caused by the fungus Sporisorium holci-sorghi (synonyms Sphacelotheca reiliana, Sorosporium reilianum and Sporisorium reilianum), are spectacular in appearance and easily distinguished. Common smut occurs worldwide wherever corn (maize) is grown, by presence of large conspicuous galls or replacement of grain kernels with smut sori. The quality of the remaining yield is often reduced by the presence of black smut spores on the surface of healthy kernels. COMMON SMUT Common smut is well known to all Illinois growers. The fungus attacks only corn–field corn (dent and flint), Indian or ornamental corn, popcorn, and sweet corn–and the closely related teosinte (Zea mays subsp. mexicana) but is most destructive to sweet corn. The smut is most prevalent on young, actively growing plants that have Figure 1. Infection of common corn smut been injured by detasseling in seed fields, hail, blowing soil or and on the ear. Smut galls are covered by the particles, insects, “buggy-whipping”, and by cultivation or spraying silvery white membrane. equipment. Corn smut differs from other cereal smuts in that any part of the plant above ground may be attacked, from the seedling stage to maturity. Losses from common smut are highly variable and rather difficult to measure, ranging from a trace up to 10 percent or more in localized areas. In rare cases, the loss in a particular field of sweet corn may approach 100 percent. -

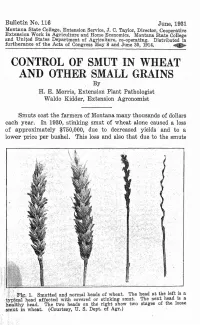

CONTROL of SMUT in WHEAT and OTHER SMALL GRAINS by H

Bulletin No. 116 June, 1931 Montana State College, Extension Service, J. C. Taylor, Director, Cooperative Extension Work in Agriculture and Home Economics. Montana State College and Uni~ed States Department of Agriculture, co-operating. Distributed in furtherance of the Acts of Congress ~ay 8 and June 30, 1.914. ~ CONTROL OF SMUT IN WHEAT AND OTHER SMALL GRAINS By H. E. Morris, Extension Plant Pathologist Waldo Kidder, Extension Agronomist Smuts cost the farmers of Montana many thousands of dollars each year. In 1930, stinking smut of wheat alone caused a loss of approximately $750;000, due to decreased yields and to a lower price per bushel. This loss and also that due to the smuts {..:Fig. 1. Smutted and normal heads of wheat. The head at the left ,is a typi:cal head affected with covered or stinking smut, The next, head IS a he'althy head. The two heads on the right show two stages of the loose smut in wheat. (-Courtesy,D. S. Dept. of Agr.) . ,( 2 MONTANA EXTENSION SERVICE of oats, barley and rye may be largely prevented by adopting the methods of seed treatment described in this bulletin. What Is Smut Smut is produced by a small parasitic plant, mould-like in appearance, belonging to a group called fungi (Fig. 2). Smut lives most of its life within and at the expense of the wheat plant. The smut powder, so familiar to all, is composed of myriads of spores which correspond to seeds in the higher plants. In the process of harvesting and threshing, these spores are dis· I Fig'. -

Physiologic Specialization Within Sphacelotheca Reiliana (Kühn) Clint

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1960 Physiologic specialization within Sphacelotheca reiliana (Kühn) Clint. on Sorghum and the Biology of its Chlamydospores in the Soil Ibrahim Aziz Al-Sohaily Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Al-Sohaily, Ibrahim Aziz, "Physiologic specialization within Sphacelotheca reiliana (Kühn) Clint. on Sorghum and the Biology of its Chlamydospores in the Soil" (1960). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2704. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/2704 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. '... PHYSIOLOGIC SPECIALIZATION WITHI.N SPHACELOTHECA REILIANA (KUHN) CLINT. ON SORGHUM AND THE BIOLOOY OF ITS CHLAMIDOSPORES I.N THE SOIL BY IBRAHIM AZIZ AL-SOHAILY A thesis suanitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Ibctor of Philosophy, Department of Plant Pathology, South Dakota State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts December, 1960 '....1 A S ATE COLLEGE LIB 7 , PHYSIOLOOIC SPECIALIZATION WITHIN SPHACELOTHECA REILIANA (Kum�) CLINT. ON SORGHUM AND THE BIOLOGY OF ITS CHLAl1YOOSPORES Ill THE SOIL Abstract IBRAIIDl AZIZ AL-SO'rIAILY Under the �ervision of Professor George Saneniuk Corresponding to the title, the present study was concerned with two aspects. In the first of these, two chlamydosporous sori from corn were collected from California and Washington and 18 chlamydosporous sori from sorghum were collected from California, New Mexico, Texas and India. -

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST and KEY for SMUT FUNGI in COLOMBIA* Lista Anotada Y Clave Para Los Ustilaginales De Colombia

Caldasia 24(1) 2002: 103-119 ANNOTATED CHECKLIST AND KEY FOR SMUT FUNGI IN COLOMBIA* Lista anotada y clave para los ustilaginales de Colombia M. PIEPENBRING Botanisches Institut, J. W. Goethe-Universität, 60054 Frankfurt, Germany. FAX: 0049 69 79824822. [email protected] ABSTRACT 71 species of smut fungi known for Colombia are cited in a checklist together with their host plants, collection data, and some comments. 20 species of smut fungi are reported for the first time for Colombia. The list includes the new species Aurantiosporium colombianum and the new combination Sporisorium concelatum. Ustilago garcesi is recognized as a synonym of Sporisorium panici-leucophaei. Four species of host plants were not yet known to be infected by the respective smut species. The smuts known for Colombia are presented in a key which contains distinctive characteristics of sori and spores. Key words. Aurantiosporium colombianum, Sporisorium concelatum, Sporisorium paspali-notati, Ustilaginales, Ustilago garcesi. RESUMEN 71 especies de carbón conocidas para Colombia se citan en una lista junto con sus plantas hospederas, datos de colección y algunos comentarios. Veinte especies de carbón se reportan por primera vez para Colombia. La lista incluye la especie nueva Aurantiosporium colombianum y la combinación nueva Sporisorium concelatum. Ustilago garcesi es un sinónimo de Sporisorium panici-leucophaei. Cuatro especies de plantas hospederas se citan por primera vez como hospedero de su respectivo carbón. Los carbones conocidos para Colombia se presentan en una clave que incluye las características distinctivas de los soros y de las esporas. Palabras clave. Aurantiosporium colombianum, Sporisorium concelatum, Ustilaginales, Ustilago garcesi. INTRODUCTION they develop usually dark, powdery masses After the rust fungi (Uredinales), the smut of teliospores (“spores”) in sori. -

Ascomycota, Leotiomycetes): a New Bambusicolous Fungal Species from North-East India

Taiwania 62(3): 261-264, 2017 DOI: 10.6165/tai.2017.62.261 Gelatinomyces conus sp. nov. (Ascomycota, Leotiomycetes): a new bambusicolous fungal species from North-East India Vipin PARKASH* Rain Forest Research Institute, Soil Microbiology Research Lab., AT Road, Sotai, Post Box No. 136, Jorhat-785001, Assam, India. *Corresponding author's email: [email protected] (Manuscript received 21 July 2016; accepted 14 June 2017; online published 17 July 2017) ABSTRACT: This study represents a newly discovered and described macro-fungal species under family Leotiomycetes (Ascomycota) named as Gelatinomyces conus sp. nov. The fungal species was collected from decayed bamboo material (leaves, culms and branches) during the survey in Upper Assam, India. It looks like a pine-cone with gelatinous ascostroma. The asci are thin-walled and arise in scattered discoid apothecia which are aggregated and clustered to form round gelatinous structure on decayed bamboo material. The study also brings the first record of fungal species from north east region of India. A taxonomic description, illustrations and isolation and culture of Gelatinomyces conus sp. nov. are provided in this study. KEY WORDS: Apothecium, Bambusicolous fungus, Gelatinous ascostroma, India, New fungal species. INTRODUCTION mounted in the DPX fixative (a mixture of distyrene (a polystyrene), a plasticizer (tricresyl phosphate), and Bamboo is like a life line in north-east India. In xylene), on the slides. Spore dimensions were obtained India, north-east states harbours bamboo in the form of under BIOXL (Labovision trinocular microscope) and homestead stands, bamboo groves (public/ private the basidiospores were microphotographed (Gogoi & domain) and natural bamboo brakes. But the knowledge Parkash 2015). -

The Effect of Low Temperature on Growth and Development of Phalaenopsis

Pak. J. Bot., 52(5): 1849-1855, 2020. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.30848/PJB2020-5(17) DEVELOPMENT OF A dCAPS MARKER BASED ON A MINOR RESISTANCE GENE RELATED TO HEAD SMUT IN BIN8.03 IN MAIZE LIN ZHANG1#, XUAN ZHOU2#, XIAOHUI SUN1, YU ZHOU1, XING ZENG1, ZHOUFEI WANG3, ZHENHUA WANG1 AND HONG DI1* 1Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin 150030, Heilongjiang Province, China 2Promotion Station of Machinery Technology for Agricultural and Animal Husbandry, Huhhot 010000, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China 3The Laboratory of Seed Science and Technology, Guangdong Key Laboratory of Plant Molecular Breeding, State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-Bioresources, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China #Lin Zhang and Xuan Zhou contributed equally to this research. *Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] Abstract Head smut can cause maize yield losses of up to 80% in the maize-growing region of Northern China. Molecular markers based on candidate resistance genes have proved to be useful for highly sensitive selection of resistance in maize breeding programs. In the present study, a SNP (single-nucleotide polymorphism) in resistant and susceptible maize lines was identified within the nucleotide-binding site (NBS)-leucine-rich repeat (LRR) gene GRMZM2G047152 in bin 8.03. Using this SNP, we developed the derived cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence marker DNdCAPS8.03-1. The molecular coincidence rate of the combination of markers DNdCAPS8.03-1 and LSdCAP2 (related to the QTL qHS2.09) was higher than that of a single marker in a set of 56 inbred maize lines belonging to five heterotic groups. These results provide information and tools that will prove to be useful in marker-assisted selection (MAS) in breeding maize for head smut resistance. -

Control of Loose Smut of Barley Richard Mullington Lewis Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1962 Control of loose smut of barley Richard Mullington Lewis Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Richard Mullington, "Control of loose smut of barley " (1962). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 2102. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/2102 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 63-1587 microfilmed exactly as received LEWIS, Richard Mullington, 1920- CONTROL OF LOOSE SMUT OF BARLEY. Iowa State University of Science and Technology Ph.D., 1962 Agriculture, plant pathology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan CONTROL OF LOOSE SMUT OF BARLEY by Richard Mullington Lewis A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Subject: Plant Pathology Approved: Signature was redacted for privacy. In Charge of Major Signature was redacted for privacy. Head of Major D rtment Signature was redacted for privacy. D^ân of Grad lollege Iowa State University Of Science and Technology Ames, Iowa 1962 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 PERTINENT LITERATURE 3 MATERIALS AND METHODS 6 Materials 6 Methods of Application 7 Seed Treatment Evaluations 12 EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS 15 1952 Results 15 1953 Results 18 195m- Results 24 1955 Results 39 DISCUSSION 41 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 48 LITERATURE CITED 51 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 53 APPENDIX 54 iii LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1. -

A Review on Rice False Smut, It's Distribution, Identification And

Acta Scientific AGRICULTURE (ISSN: 2581-365X) Volume 4 Issue 12 December 2020 Review Article A Review on Rice False Smut, it’s Distribution, Identification and Management Practices Bhanu Dangi1*, Saugat Khanal2 and Shubekshya Shah3 Received: October 27, 2020 1Sahara Multipurpose Agriculture Farm, Tulsipur, Dang, Nepal Published: 2Faculty of Agriculture, Agriculture and Forestry University, Rampur, Chitwan, Bhanu Dangi., Nepal November 21, 2020 et al. 3Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science, Tribhuvan University, Nepal © All rights are reserved by *Corresponding Author: Bhanu Dangi, Sahara Multipurpose Agriculture Farm, Tulsipur, Dang, Nepal. Abstract Rice (Oryza sativa Villosiclava virens is the ) is the major source of food security for most of the population in the world. False smut is recently emerging as a major Rice disease which was previously considered to have a negligible impact. An ascomycetes fungus, pathogen that causes the False Smut disease of rice. It is found in two different stages sexual and asexual and both spores can infect the spikelet and lead to the formation of smut ball of rice grain. The disease has been reported from all across the world after being reported for the first time in Tamil Nadu by Cooke in 1878. Rice False Smut has been reported to cause 40% of the yield losses and this disease can be controlled with the proper management practices and the control approaches. The disease is found to have linked with the higher nitrogen usages and the occurrence of heavy rainfall during Reproductive stage. Preventive approaches include crop rotation, optimum nitrogen usages, selection of the resistant variety, scheduling of the crop plantation to avoid raining during in vitro and in vivo sensitive stages and field preparation. -

Comparative Analysis of the Maize Smut Fungi Ustilago Maydis and Sporisorium Reilianum

Comparative Analysis of the Maize Smut Fungi Ustilago maydis and Sporisorium reilianum Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) dem Fachbereich Biologie der Philipps-Universität Marburg vorgelegt von Bernadette Heinze aus Johannesburg Marburg / Lahn 2009 Vom Fachbereich Biologie der Philipps-Universität Marburg als Dissertation angenommen am: Erstgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Regine Kahmann Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael Bölker Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: Die Untersuchungen zur vorliegenden Arbeit wurden von März 2003 bis April 2007 am Max-Planck-Institut für Terrestrische Mikrobiologie in der Abteilung Organismische Interaktionen unter Betreuung von Dr. Jan Schirawski durchgeführt. Teile dieser Arbeit sind veröffentlicht in : Schirawski J, Heinze B, Wagenknecht M, Kahmann R . 2005. Mating type loci of Sporisorium reilianum : Novel pattern with three a and multiple b specificities. Eukaryotic Cell 4:1317-27 Reinecke G, Heinze B, Schirawski J, Büttner H, Kahmann R and Basse C . 2008. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) biosynthesis in the smut fungus Ustilago maydis and its relevance for increased IAA levels in infected tissue and host tumour formation. Molecular Plant Pathology 9(3): 339-355. Erklärung Erklärung Ich versichere, dass ich meine Dissertation mit dem Titel ”Comparative analysis of the maize smut fungi Ustilago maydis and Sporisorium reilianum “ selbständig, ohne unerlaubte Hilfe angefertigt und mich dabei keiner anderen als der von mir ausdrücklich bezeichneten Quellen und Hilfen bedient habe. Diese Dissertation wurde in der jetzigen oder einer ähnlichen Form noch bei keiner anderen Hochschule eingereicht und hat noch keinen sonstigen Prüfungszwecken gedient. Ort, Datum Bernadette Heinze In memory of my fathers Jerry Goodman and Christian Heinze. “Every day I remind myself that my inner and outer life are based on the labors of other men, living and dead, and that I must exert myself in order to give in the same measure as I have received and am still receiving.