A Short History of Computer Chess, Including Some of the Best Man-Machine and Machine-Machine Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virginia Chess Federation 2010 - #4

VIRGINIA CHESS Newsletter The bimonthly publication of the Virginia Chess Federation 2010 - #4 -------- Inside... / + + + +\ Charlottesville Open /+ + + + \ Virginia Senior Championship / N L O O\ Tim Rogalski - King of the Open Sicilian 2010 State Championship announcement/+p+pO Op\ and more, including... / Pk+p+p+\ Larry Larkins revisits/+ + +p+ \ the Yeager-Perelshteyn ending/ + + + +\ /+ + + + \ ________ VIRGINIA CHESS Newsletter 2010 - Issue #4 Editor: Circulation: Macon Shibut Ernie Schlich 8234 Citadel Place 1370 South Braden Crescent Vienna VA 22180 Norfolk VA 23502 [email protected] [email protected] k w r Virginia Chess is published six times per year by the Virginia Chess Federation. Membership benefits (dues: $10/yr adult; $5/yr junior under 18) include a subscription to Virginia Chess. Send material for publication to the editor. Send dues, address changes, etc to Circulation. The Virginia Chess Federation (VCF) is a non-profit organization for the use of its members. Dues for regular adult membership are $10/yr. Junior memberships are $5/yr. President: Mike Hoffpauir, 405 Hounds Chase, Yorktown VA 23693, mhoffpauir@ aol.com Treasurer: Ernie Schlich, 1370 South Braden Crescent, Norfolk VA 23502, [email protected] Secretary: Helen Hinshaw, 3430 Musket Dr, Midlothian VA 23113, [email protected] Tournaments: Mike Atkins, PO Box 6138, Alexandria VA, [email protected] Scholastics Coordinator: Mike Hoffpauir, 405 Hounds Chase, Yorktown VA 23693, [email protected] VCF Inc Directors: Helen Hinshaw (Chairman), Rob Getty, John Farrell, Mike Hoffpauir, Ernie Schlich. otjnwlkqbhrp 2010 - #4 1 otjnwlkqbhrp Charlottesville Open by David Long INTERNATIONAL MASTER OLADAPO ADU overpowered a field of 54 Iplayers to win the Charlottesville Open over the July 10-11 weekend. -

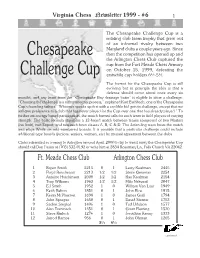

1999/6 Layout

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

100 Years of Shannon: Chess, Computing and Botvinik Iryna Andriyanova

100 Years of Shannon: Chess, Computing and Botvinik Iryna Andriyanova To cite this version: Iryna Andriyanova. 100 Years of Shannon: Chess, Computing and Botvinik. Doctoral. United States. 2016. cel-01709767 HAL Id: cel-01709767 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/cel-01709767 Submitted on 15 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CLAUDE E. SHANNON 1916—2001 • 1936 : Bachelor in EE and Mathematics from U.Michigan • 1937 : Master in EE from MIT • 1940 : PhD in EE from MIT • 1940 : Research fellow at Princeton • 1940-1956 : Researcher at Bell Labs • 1948 : “A Mathematical Theory of Communication”, Bell System Technical Journal • 1956-1978 : Professor at MIT 100 YEARS OF SHANNON SHANNON, BOTVINNIK AND COMPUTER CHESS Iryna Andriyanova ETIS Lab, UMR 8051, ENSEA/Université de Cergy-Pontoise/CNRS 54TH ALLERTON CONFERENCE SHORT HISTORY OF CHESS/COMPUTER CHESS CHESS AND COMPUTER CHESS TWO PARALLELS W. Steinitz M. Botvinnik A. Karpov 1886 1894 1921 1948 1963 1975 1985 2006* E. Lasker G. Kasparov W. Steinitz: simplicity and rationality E. Lasker: more risky play M. Botvinnik: complicated, very original positions A. Karpov, G. Kasparov: Botvinnik’s school CHESS AND COMPUTER CHESS TWO PARALLELS W. -

Learning Long-Term Chess Strategies from Databases

Mach Learn (2006) 63:329–340 DOI 10.1007/s10994-006-6747-7 TECHNICAL NOTE Learning long-term chess strategies from databases Aleksander Sadikov · Ivan Bratko Received: March 10, 2005 / Revised: December 14, 2005 / Accepted: December 21, 2005 / Published online: 28 March 2006 Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2006 Abstract We propose an approach to the learning of long-term plans for playing chess endgames. We assume that a computer-generated database for an endgame is available, such as the king and rook vs. king, or king and queen vs. king and rook endgame. For each position in the endgame, the database gives the “value” of the position in terms of the minimum number of moves needed by the stronger side to win given that both sides play optimally. We propose a method for automatically dividing the endgame into stages characterised by different objectives of play. For each stage of such a game plan, a stage- specific evaluation function is induced, to be used by minimax search when playing the endgame. We aim at learning playing strategies that give good insight into the principles of playing specific endgames. Games played by these strategies should resemble human expert’s play in achieving goals and subgoals reliably, but not necessarily as quickly as possible. Keywords Machine learning . Computer chess . Long-term Strategy . Chess endgames . Chess databases 1. Introduction The standard approach used in chess playing programs relies on the minimax principle, efficiently implemented by alpha-beta algorithm, plus a heuristic evaluation function. This approach has proved to work particularly well in situations in which short-term tactics are prevalent, when evaluation function can easily recognise within the search horizon the con- sequences of good or bad moves. -

Kasparov's Nightmare!! Bobby Fischer Challenges IBM to Simul IBM

California Chess Journal Volume 20, Number 2 April 1st 2004 $4.50 Kasparov’s Nightmare!! Bobby Fischer Challenges IBM to Simul IBM Scrambles to Build 25 Deep Blues! Past Vs Future Special Issue • Young Fischer Fires Up S.F. • Fischer commentates 4 Boyscouts • Building your “Super Computer” • Building Fischer’s Dream House • Raise $500 playing chess! • Fischer Articles Galore! California Chess Journal Table of Con tents 2004 Cal Chess Scholastic Championships The annual scholastic tourney finishes in Santa Clara.......................................................3 FISCHER AND THE DEEP BLUE Editor: Eric Hicks Contributors: Daren Dillinger A miracle has happened in the Phillipines!......................................................................4 FM Eric Schiller IM John Donaldson Why Every Chess Player Needs a Computer Photographers: Richard Shorman Some titles speak for themselves......................................................................................5 Historical Consul: Kerry Lawless Founding Editor: Hans Poschmann Building Your Chess Dream Machine Some helpful hints when shopping for a silicon chess opponent........................................6 CalChess Board Young Fischer in San Francisco 1957 A complet accounting of an untold story that happened here in the bay area...................12 President: Elizabeth Shaughnessy Vice-President: Josh Bowman 1957 Fischer Game Spotlight Treasurer: Richard Peterson One game from the tournament commentated move by move.........................................16 Members at -

Virginia Chess Federation 2008 - #6

VIRGINIA CHESS Newsletter The bimonthly publication of the Virginia Chess Federation 2008 - #6 Grandmaster Larry Kaufman See page 1 VIRGINIA CHESS Newsletter 2008 - Issue #6 Editor: Circulation: Macon Shibut Ernie Schlich 8234 Citadel Place 1370 South Braden Crescent Vienna VA 22180 Norfolk VA 23502 [email protected] [email protected] k w r Virginia Chess is published six times per year by the Virginia Chess Federation. Membership benefits (dues: $10/yr adult; $5/yr junior under 18) include a subscription to Virginia Chess. Send material for publication to the editor. Send dues, address changes, etc to Circulation. The Virginia Chess Federation (VCF) is a non-profit organization for the use of its members. Dues for regular adult membership are $10/yr. Junior memberships are $5/yr. President: Mike Hoffpauir, 405 Hounds Chase, Yorktown VA 23693, mhoffpauir@ aol.com Treasurer: Ernie Schlich, 1370 South Braden Crescent, Norfolk VA 23502, [email protected] Secretary: Helen Hinshaw, 3430 Musket Dr, Midlothian VA 23113, jallenhinshaw@comcast. net Scholastics Coordinator: Mike Hoffpauir, 405 Hounds Chase, Yorktown VA 23693, [email protected] VCF Inc. Directors: Helen Hinshaw (Chairman), Rob Getty, John Farrell, Mike Hoffpauir, Ernie Schlich. otjnwlkqbhrp 2008 - #6 1 otjnwlkqbhrp Larry Kaufman, of Maryland, is a familiar face at Virginia tournaments. Among others he won the Virginia Open in 1969, 1998, 2000, 2006 and 2007! Recently Larry achieved a lifelong goal by attaining the title of International Grandmaster, and agreed to tell VIRGINIA CHESS readers how it happened. -ed World Senior Chess Championship by Larry Kaufman URING THE LAST FIVE YEARS OR SO, whenever someone asked me Dif I still hoped to become a GM, I would reply something like this: “I’m too old now to try to do it the normal way, but perhaps when I reach 60 I will try to win the World Senior, which carries an automatic GM title. -

Extended Null-Move Reductions

Extended Null-Move Reductions Omid David-Tabibi1 and Nathan S. Netanyahu1,2 1 Department of Computer Science, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan 52900, Israel [email protected], [email protected] 2 Center for Automation Research, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA [email protected] Abstract. In this paper we review the conventional versions of null- move pruning, and present our enhancements which allow for a deeper search with greater accuracy. While the conventional versions of null- move pruning use reduction values of R ≤ 3, we use an aggressive re- duction value of R = 4 within a verified adaptive configuration which maximizes the benefit from the more aggressive pruning, while limiting its tactical liabilities. Our experimental results using our grandmaster- level chess program, Falcon, show that our null-move reductions (NMR) outperform the conventional methods, with the tactical benefits of the deeper search dominating the deficiencies. Moreover, unlike standard null-move pruning, which fails badly in zugzwang positions, NMR is impervious to zugzwangs. Finally, the implementation of NMR in any program already using null-move pruning requires a modification of only a few lines of code. 1 Introduction Chess programs trying to search the same way humans think by generating “plausible” moves dominated until the mid-1970s. By using extensive chess knowledge at each node, these programs selected a few moves which they consid- ered plausible, and thus pruned large parts of the search tree. However, plausible- move generating programs had serious tactical shortcomings, and as soon as brute-force search programs such as Tech [17] and Chess 4.x [29] managed to reach depths of 5 plies and more, plausible-move generating programs fre- quently lost to brute-force searchers due to their tactical weaknesses. -

{Download PDF} Kasparov Versus Deep Blue : Computer Chess

KASPAROV VERSUS DEEP BLUE : COMPUTER CHESS COMES OF AGE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Monty Newborn | 322 pages | 31 Jul 2012 | Springer-Verlag New York Inc. | 9781461274773 | English | New York, NY, United States Kasparov versus Deep Blue : Computer Chess Comes of Age PDF Book In terms of human comparison, the already existing hierarchy of rated chess players throughout the world gave engineers a scale with which to easily and accurately measure the success of their machine. This was the position on the board after 35 moves. Nxh5 Nd2 Kg4 Bc7 Famously, the mechanical Turk developed in thrilled and confounded luminaries as notable as Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin. Kf1 Bc3 Deep Blue. The only reason Deep Blue played in that way, as was later revealed, was because that very same day of the game the creators of Deep Blue had inputted the variation into the opening database. KevinC The allegation was that a grandmaster, presumably a top rival, had been behind the move. When it's in the open, anyone could respond to them, including people who do understand them. Qe2 Qd8 Bf3 Nd3 IBM Research. Nearly two decades later, the match still fascinates This week Time Magazine ran a story on the famous series of matches between IBM's supercomputer and Garry Kasparov. Because once you have an agenda, where does indifference fit into the picture? Raa6 Ba7 Black would have acquired strong counterplay. In fact, the first move I looked at was the immediate 36 Be4, but in a game, for the same safety-first reasons the black counterplay with a5 I might well have opted for 36 axb5. -

PUBLIC SUBMISSION Status: Pending Post Tracking No

As of: January 02, 2020 Received: December 20, 2019 PUBLIC SUBMISSION Status: Pending_Post Tracking No. 1k3-9dz4-mt2u Comments Due: January 10, 2020 Submission Type: Web Docket: PTO-C-2019-0038 Request for Comments on Intellectual Property Protection for Artificial Intelligence Innovation Comment On: PTO-C-2019-0038-0002 Intellectual Property Protection for Artificial Intelligence Innovation Document: PTO-C-2019-0038-DRAFT-0009 Comment on FR Doc # 2019-26104 Submitter Information Name: Yale Robinson Address: 505 Pleasant Street Apartment 103 Malden, MA, 02148 Email: [email protected] General Comment In the attached PDF document, I describe the history of chess puzzle composition with a focus on three intellectual property issues that determine whether a chess composition is considered eligible for publication in a magazine or tournament award: (1) having one unique solution; (2) not being anticipated, and (3) not being submitted simultaneously for two different publications. The process of composing a chess endgame study using computer analysis tools, including endgame tablebases, is cited as an example of the partnership between an AI device and a human creator. I conclude with a suggestion to distinguish creative value from financial profit in evaluating IP issues in AI inventions, based on the fact that most chess puzzle composers follow IP conventions despite lacking any expectation of financial profit. Attachments Letter to USPTO on AI and Chess Puzzle Composition 35 - Robinson second submission - PTO-C-2019-0038-DRAFT-0009.html[3/11/2020 9:29:01 PM] December 20, 2019 From: Yale Yechiel N. Robinson, Esq. 505 Pleasant Street #103 Malden, MA 02148 Email: [email protected] To: Andrei Iancu Director of the U.S. -

Chapter 15, New Pieces

Chapter 15 New pieces (2) : Pieces with limited range [This chapter covers pieces whose range of movement is limited, in the same way that the moves of the king and knight are limited in orthochess.] 15.1 Pieces which can move only one square [The only such piece in orthochess is the king, but the ‘wazir’ (one square orthogonally in any direction), ‘fers’ or ‘firzan’ (one square diagonally in any direction), ‘gold general’ (as wazir and also one square diagonally forward), and ‘silver general’ (as fers and also one square orthogonally forward), have been widely used and will be found in many of the games in the chapters devoted to historical and regional versions of chess. Some other flavours will be found below. In general, games which involve both a one-square mover and ‘something more powerful’ will be found in the section devoted to ‘something more powerful’, but the two later developments of ‘Le Jeu de la Guerre’ are included in this first section for convenience. One-square movers are slow and may seem to be weak, but even the lowly fers can be a potent attacking weapon. ‘Knight for two pawns’ is rarely a good swap, but ‘fers for two pawns’ is a different matter, and a sound tactic, when unobservant defence permits it, is to use the piece with a fers move to smash a hole in the enemy pawn structure so that other men can pour through. In xiangqi (Chinese chess) this piece is confined to a defensive role by the rules of the game, but to restrict it to such a role in other forms of chess may well be a losing strategy.] Le Jeu de la Guerre [M.M.] (‘M.M.’, ranks 1/11, CaHDCuGCaGCuDHCa on ranks perhaps J. -

Computer Chess Methods

COMPUTER CHESS METHODS T.A. Marsland Computing Science Department, University of Alberta, EDMONTON, Canada T6G 2H1 ABSTRACT Article prepared for the ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, S. Shapiro (editor), D. Eckroth (Managing Editor) to be published by John Wiley, 1987. Final draft; DO NOT REPRODUCE OR CIRCULATE. This copy is for review only. Please do not cite or copy. Acknowledgements Don Beal of London, Jaap van den Herik of Amsterdam and Hermann Kaindl of Vienna provided helpful responses to my request for de®nitions of technical terms. They and Peter Frey of Evanston also read and offered constructive criticism of the ®rst draft, thus helping improve the basic organization of the work. In addition, my many friends and colleagues, too numerous to mention individually, offered perceptive observations. To all these people, and to Ken Thompson for typesetting the chess diagrams, I offer my sincere thanks. The experimental work to support results in this article was possible through Canadian Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Grant A7902. December 15, 1990 COMPUTER CHESS METHODS T.A. Marsland Computing Science Department, University of Alberta, EDMONTON, Canada T6G 2H1 1. HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Of the early chess-playing machines the best known was exhibited by Baron von Kempelen of Vienna in 1769. Like its relations it was a conjurer's box and a grand hoax [1, 2]. In contrast, about 1890 a Spanish engineer, Torres y Quevedo, designed a true mechanical player for king-and-rook against king endgames. A later version of that machine was displayed at the Paris Exhibition of 1914 and now resides in a museum at Madrid's Polytechnic University [2]. -

A More Human Way to Play Computer Chess

DCS 17 January 2019 A More Human Way to Play Computer Chess Kieran Greer, Distributed Computing Systems, Belfast, UK. http://distributedcomputingsystems.co.uk Version 1.1 Abstract— This paper suggests a forward-pruning technique for computer chess that uses ‘Move Tables’, which are like Transposition Tables, but for moves not positions. They use an efficient memory structure and has put the design into the context of long and short-term memories. The long-term memory updates a play path with weight reinforcement, while the short-term memory can be immediately added or removed. With this, ‘long branches’ can play a short path, before returning to a full search at the resulting leaf nodes. Re-using an earlier search path allows the tree to be forward-pruned, which is known to be dangerous, because it removes part of the search process. Additional checks are therefore made and moves can even be re-added when the search result is unsatisfactory. Automatic feature analysis is now central to the algorithm, where key squares and related squares can be generated automatically and used to guide the search process. Using this analysis, if a search result is inferior, it can re-insert un-played moves that cover these key squares only. On the tactical side, a type of move that the forward-pruning will fail on is recognised and a pattern-based solution to that problem is suggested. This has completed the theory of an earlier paper and resulted in a more human-like approach to searching for a chess move. Tests demonstrate that the obvious blunders associated with forward pruning are no longer present and that it can compete at the top level with regard to playing strength.