The Internet's Democratization Effect in Authoritarianisms with Adjectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Internet and Regulatory Responses in Ethiopia: Telecoms, Cybercrimes, Privacy, E-Commerce, and the New Media

The Internet and Regulatory Responses in Ethiopia: Telecoms, Cybercrimes, Privacy, E-commerce, and the New Media Kinfe Micheal Yilma . and Halefom Hailu Abraha.. Abstract Whilst Ethiopia has telephone services since 1894 − not long after its invention−, the history of the Internet in Ethiopia is less than two decades old. The prototype Internet with limited accessibility was introduced only in 1997, and broadband Internet was not widely deployed until recently. This slow pace in the proliferation of the Internet has delayed the legislative responses of the country to the brave new worlds of the Internet. Despite a few laws currently in operation namely the cybercrime and telecom fraud offence laws, most areas of the online environment needs the attention of the Ethiopian legislature. Nonetheless, there are few draft cyber laws that are in the pipeline. This article briefly reviews major legislative developments in telecoms, cybercrime, privacy, e-commerce and the new media. It sketches legislative responses of the Ethiopian legislature to the advent of the Internet by outlining major sources of Internet law and their defining features. The article further considers the salient features of the major draft pieces of cyber legislation that await enactment. Key terms Internet, information technology, telecommunications, cyber law, Internet law, e-commerce, Ethiopia DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mlr.v9i1.4 Acronyms CA Certification Authority DESL Draft Electronic Signature Law DETL Draft Electronic Transactions Law DoS Denial of Service Attacks . Kinfe Micheal Yilma (LLB, Addis Ababa University; LLM, University of Oslo; LLM, Brunel University London). The author was formerly a Lecturer-in-Law at Hawassa University. -

Human Rights Violations in Ethiopia

/ w / %w '* v *')( /)( )% +6/& $FOUFSGPS*OUFSOBUJPOBM)VNBO3JHIUT-BX"EWPDBDZ 6OJWFSTJUZPG8ZPNJOH$PMMFHFPG-BX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by University of Wyoming College of Law students participating in the Fall 2017 Human Rights Practicum: Jennie Boulerice, Catherine Di Santo, Emily Madden, Brie Richardson, and Gabriela Sala. The students were supervised and the report was edited by Professor Noah Novogrodsky, Carl M. Williams Professor of Law and Ethics and Director the Center for Human Rights Law & Advocacy (CIHRLA), and Adam Severson, Robert J. Golten Fellow of International Human Rights. The team gives special thanks to Julia Brower and Mark Clifford of Covington & Burling LLP for drafting the section of the report addressing LGBT rights, and for their valuable comments and edits to other sections. We also thank human rights experts from Human Rights Watch, the United States Department of State, and the United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office for sharing their time and expertise. Finally, we are grateful to Ethiopian human rights advocates inside and outside Ethiopia for sharing their knowledge and experience, and for the courage with which they continue to document and challenge human rights abuses in Ethiopia. 1 DIVIDE, DEVELOP, AND RULE: HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN ETHIOPIA CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW & ADVOCACY UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING COLLEGE OF LAW 1. PURPOSE, SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY 3 2. INTRODUCTION 3 3. POLITICAL DISSENTERS 7 3.1. CIVIC AND POLITICAL SPACE 7 3.1.1. Elections 8 3.1.2. Laws Targeting Dissent 14 3.1.2.1. Charities and Society Proclamation 14 3.1.2.2. Anti-Terrorism Proclamation 17 3.1.2.3. -

A Survey of ICT Access and Usage in Ethiopia

ICT POLICY BRIEF NO.1 A Survey of ICT Access and Usage in Ethiopia: Policy Implications Executive Summary This policy brief presents a synthesis of the results of household survey on ICT access and usage that was conducted in Ethiopia and other 16 African countries at the end of 2007 and the beginning of 2008. The data were collected from a national sample of 2100 households. The survey covered 84 Enumeration Areas (EA) that were randomly selected based on the data available from the Central Statistics Agency. Major urban, urban and rural areas from Tigray, Amhara, SNNPR, Somali, Afar, Benshangul Gumuz, Oromiya, Hareri, Dire Dawa and Addis Ababa regions were covered to provide an overall picture of the state of ICT access and usage in the country. The paper synthesises the results of the ICT access and usage survey in comparison to other African countries and provides policy recommendations for actions. households that dwell in the same compounds; that has 1. Introduction inflated the figure slightly. Notwithstanding the relatively The Government of Ethiopia has made a significant progress high level of penetration, there is still a long way to go in in increasing access to the ICT in the recent years. The fixed bridging the access gap to fixed line network in the country, line penetration has reached 1.2% with mobile penetration in particular in rural areas. well above 3% in 2008. Progress was also made in the rural access front, particularly in connecting rural towns that did not have access to modern information and communication technologies. The incumbent’s (Ethiopian Telecommunica‐ tions Corporation) stations were expanded to 936 places mostly in rural towns. -

Ethiopia June 2014—May 2015

Ethiopia Page 1 of 18 Published on Freedom House (https://freedomhouse.org) Home > Ethiopia Ethiopia Country: Ethiopia Year: 2015 Status: Not Free Total Score: 82 (0 = Best, 100 = Worst) Obstacles to Access: 23 (0 = Best, 25 = Worst) Limits on Content: 28 (0 = Best, 35 = Worst) Violations of User Rights: 31 (0 = Best, 40 = Worst) Internet Penetration: 2.9 percent Social Media/ICT Apps Blocked: Yes Political/Social Content Blocked: Yes Bloggers/ICT Users Arrested: Yes Press Freedom Status: Not Free Key Developments: June 2014—May 2015 https://freedomhouse.org/print/47663 12/8/2016 Ethiopia Page 2 of 18 • A significant number of service interruptions in the name of routine maintenance and system updates resulted in worsening service across the country. Internet services on 3G mobile internet networks were reportedly unavailable for more than a month in July and August 2014 (see Restrictions on Connectivity). • A growing number of critical news and opposition websites were blocked in the lead up to the May 2015 elections (see Blocking and Filtering). • Six bloggers of the prominent Zone 9 blogging collective arrested in April 2014 were officially charged with terrorism in July 2014; two of the bloggers were unexpectedly released and acquitted in July 2015, joined by the four others in October (see Prosecutions and Arrests). • A university political science teacher known for his Facebook activism and another blogger were arrested and charged with terrorism in July 2014, among three others (see Prosecutions and Arrests). • Online journalists in the Ethiopian diaspora were attacked with Hacking Team’s sophisticated surveillance malware (see Technical Attacks). -

THE CASE of Graduate Students in Addis Ababa University

Patterns of internet and newspaper use in ethiopia: THE CASE OF Graduate students in addis ababa university A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM AND COMMUNICATION BY SOPHia nesri july, 2006 Acknowledgement Writing this thesis was not an accomplishment of my own. First and foremost, I wish to thank God for all that has been and will be accomplished. Among the many people to whom I owe my deepest gratitude, respect and affection, my mother, Yeshihareg Retta, deserve the most special place. Her love and prayers were a foundation for my work. I owe the greatest thanks to Amare Asgedom and Dr. Nicolas Jones, my advisors, for their very helpful comments and suggestions during the revision of this paper. Their useful suggestions and constructive comments have significantly improved the quality of this work. Particular recognition must go to my boss and colleagues who made me endure the ups and downs during the past two, very busy years of my life. I especially want to thank Marc Rubin, Stefano Pizzi, Fikre Negussie and Seydou Dia who juggled priorities by providing me time to conduct my research while still running humanitarian programmes in Ethiopia. In addition, I owe many thanks to Hawi Busa who contributed significantly to this work. I want to thank him for his great insights and all his contributions to the data analysis. In particular, I would like to recognize the contributions of Meron Berhane for generously giving her time and the many good suggestions on various aspects of the work. -

Ethiopia Digital Rights Landscape Report

ids.ac.uk Digital Rights in Closing Civic Space: Lessons from Ten African Countries 185 Ethiopia Digital Rights Landscape Report Ethiopia Digital Rights Landscape Report Iginio Gagliardone and Atnafu Brhane This is an Open Access report distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated. This report is part of ‘Digital Rights in Closing Civic Space: Lessons from Ten African Countries’; the Introduction is also recommended reading. © 2021 Iginio Gagliardone & Atnafu Brhane © Institute of Development Studies. DOI: 10.19088/IDS.2021.013 ids.ac.uk Digital Rights in Closing Civic Space: Lessons from Ten African Countries 186 Ethiopia Digital Rights Landscape Report 1. Introduction Ethiopia is a country of many paradoxes. It has some of the lowest levels of internet penetration in the world, yet applies some of the severest measures for surveilling and censoring online communication (HRW 2014). It has charted new avenues of collaboration with emerging donors, especially China, but also continues to be Africa’s largest recipient of development aid from traditional Western donors (Fourie 2015; Gagliardone 2019). Ethiopia has championed uses of information and communication technologies (ICTs) that have later been adopted elsewhere in Africa, from videoconferencing for government communication to commodities exchanges, and yet it is considered backward when it comes to digital innovation (Rashid 2015). The Ethiopian government, led since 1991 by the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) coalition, has developed a distinctive approach towards digital media in Africa. -

Operating Digital Gig Platforms in Different Regulatory Environments

OPERATING DIGITAL GIG PLATFORMS IN DIFFERENT REGULATORY ENVIRONMENTS OPERATING DIGITAL GIG PLATFORMS IN DIFFERENT REGULATORY ENVIRONMENTS A comparative assessment of Kenya, Tanzania, and Ethiopia FINAL REPORT : JUNE 2020 1 OPERATING DIGITAL GIG PLATFORMS IN DIFFERENT REGULATORY ENVIRONMENTS Acknowledgements Mercy Corps’ Youth Impact Labs (YIL) commissioned Open Capital to conduct this comparative assessment of the digital gig economies in Kenya, Tanzania, and Ethiopia, with a focus on the regulatory environments in those three markets. The findings in this report were developed through consultations with key stakeholders in the digital gig economy eco-system including digital gig platform operators, research bodies, legal experts, and tax experts. We would like to thank the Open Capital research team for interviewing the different stake- holders and preparing this report. We would especially like to thank our interview participants for sharing their views on the digital gig economy – without their insights this study would not have been possible. Youth Impact Labs Catalyzed by funding from Google.org, Mercy Corps’ YIL identifies and tests creative, technology-enabled solutions to tackle global youth unemployment, accelerating job creation to enable every young person to access opportunities for dignified, purposeful work. Focusing on vulnerable youth aged 15 – 35, YIL operates in two strategic regional hubs, serving the Middle East and East Africa. In Kenya, YIL focuses on digital marketplaces and platforms that offer services to micro and small enterprises; agricultural supply chain management; and digital work. The program supports these enterprises through fi- nancial and technical support; issued in the form of milestone-based grants. 2 OPERATING DIGITAL GIG PLATFORMS IN DIFFERENT REGULATORY ENVIRONMENTS Contents 5 Executive Summary 10 1. -

Ethiopia Country Report | Freedom on the Net 2018

Ethiopia Country Report | Freedom on the Net https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2018/ethiopia Ethiopia Country Report | Freedom on the Net Internet Freedom Score 13/25 Most Free (0) Least Free (100) Obstacles to access 23/25 Limits on content 29/35 Violations of users rights 31/40 Key Developments: May 31, 2017 - June 1, 2018 Internet access improved slightly though remained low during the coverage period (see Availability and Ease of Access). The government under former Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn responded to ongoing antigovernment protests with frequent internet shutdowns and blocks on social media, though access was restored in April 2018 under the new prime minister (see Restrictions on Connectivity). A few blocked websites became accessible in May 2018, while hundreds more were unblocked in June, reflecting the new government’s openness to critical voices and independent news (see Blocking and Filtering). Online self-censorship decreased palpably as citizens flocked to social media to participate in their country’s transition from authoritarianism (see Media, Diversity, and Manipulation). Following the resignation of Prime Minister Desalegn, the authorities imposed a six-month state of emergency that placed restrictions on certain online activities to quell antigovernment unrest (see Legal Environment). In a positive step, the ruling EPRDF party released hundreds of political prisoners, including imprisoned bloggers, before his resignation—a trend that new Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed continued. A few bloggers were arrested for short periods during the state of emergency (see Prosecutions and Arrests for Online Activities). Introduction: Internet freedom in Ethiopia remained highly restricted during the coverage period but saw incremental improvements following the resignation of former Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn in February 2018 and the appointment of Abiy Ahmed to the seat in April. -

A Sampling of Blocked Websites in Ethiopia

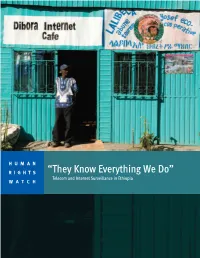

HUMAN RIGHTS “They Know Everything We Do” Telecom and Internet Surveillance in Ethiopia WATCH “They Know Everything We Do” Telecom and Internet Surveillance in Ethiopia Copyright © 2014 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-1159 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.Human Rights Watch.org MARCH 2014 978-1-62313-1159 “They Know Everything We Do” Telecom and Internet Surveillance in Ethiopia Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................. -

July 29, 2021 #Keepiton in Tigray: Ethiopia Must Li the Blackout From

July 29, 2021 #KeepItOn in Tigray: Ethiopia must li the blackout from conflict zone Access to the internet and all telecommunications services must be restored across the Tigray region. The #KeepItOn Coalition — a global network of human rights organizations that work to end internet shutdowns — is increasingly alarmed by the human rights violations carried out in the region of Tigray during the ongoing conflict, and the increasing use of censorship techniques to conceal them. Since the start of the conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region in November 2020, internet and telecommunication shutdowns, as well as alleged blocking of specific websites, have been used as a weapon of information control and censorship by involved parties. On June 28, aer the capital, Mekele, was taken by Tigrayan troops and the Ethiopian government declared an unilateral ceasefire — a condition of which was the restoration of essential and communication services — Tigray was once again put under a complete communication blackout. Although connectivity was restored in certain areas in 2020, it is sporadic and intermittent. Broadband and mobile internet remains off, while disconnected phone lines and constant power shortages have rendered satellite internet connections almost unattainable. Ostensibly, Tigray is blacked out, and cut off from the rest of the world, further aggravating the abuses committed in the region. It is increasingly difficult for journalists, human rights activists, and humanitarian NGOs to corroborate accounts of human rights violations. Devastating human rights abuses concealed Although information emerging from the region has been slow, numerous accusations of troops from Ethiopia and Eritrea, and the Amhara militia, committing heinous crimes against civilians have come out. -

The Evolution of the Internet in Ethiopia and Rwanda: Towards A

Gagliardone, I and Golooba-Mutebi, F 2016 The Evolution of the Internet in Ethiopia and Rwanda: Towards a “Developmental” Model? Stability: stability International Journal of Security & Development, 5(1): 8, pp. 1–24, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/sta.344 RESEARCH ARTICLE The Evolution of the Internet in Ethiopia and Rwanda: Towards a “Developmental” Model? Iginio Gagliardone* and Frederick Golooba-Mutebi† The Internet in Africa has become an increasingly contested space, where com- peting ideas of development and society battle for hegemony. By comparing the evolution of the Internet in Ethiopia and Rwanda, we question whether policies and projects emerging from two of Africa’s fastest growing, but also most tightly controlled countries, can be understood as part of a relatively cohesive model of the ‘developmental’ Internet, which challenges mainstream conceptions. Our answer is a qualified yes. Ethiopia and Rwanda have shared an overarching strategy which places the state as the prime mover in the development of Internet policy and large-scale ICT projects. Rwanda, however, appears to have developed a more open model which can accommodate a greater variety of actors and opinions, and incorporate them within a relatively coherent vision that emanates from the centre. Ethiopia, in contrast, has developed a more closed model, where all powers rest firmly in the hands of a government that has refused (so far) to entertain and engage with alternative ideas of the Internet. In the case of Rwanda, we argue, this approach reflects broader strategies adopted by the government in the economic domain but appears to counter the prevailing political approach of the government, allowing for a greater degree of freedom on the Internet as compared to traditional media. -

Sam Kassegne

Curriculum Vitae Of SAMUEL KINDE KASSEGNE 7162 Pintail Dr., Carlsbad, CA 92009 Tel: (760)-402-7162, (760)-438-2715 (H) E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering Mechanics, December 1992. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (VPI&SU), Blacksburg, VA. Dissertation: Layerwise Theory for Discretely Stiffened Laminated Cylindrical Shells. Doctoral Advisor: Professor J.N. Reddy. Master of Science in Civil Engineering, June 1987. Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey. Thesis: Numerical Analysis of Box Girders by the Nodal Section Method. Advisor: Professor Tanvir Wasti. Bachelor of Engineering in Civil Engineering, December 1984. College of Engineering, Anna University, Madras, India. Graduated in First Class Distinction. Supervisor: Professor L. Elangovan. Courses from UCSD (University of California at San Diego) in OOP, MFC and Visual C/C++ programming. TEACHING EXPERIENCE 1/03 – Present Visiting Scientist/Lecturer at University of California - Irvine (UCI), Irvine, CA 92697. Theory of Machines and Mechanisms (Spring 03). A 4-units course for juniors and seniors in Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at the Henri Samueli School of Engineering. 9/99 – Present Faculty Member at University of California - San Diego (UCSD) Extension, La Jolla, San Diego, CA 92093. Finite Element Principles and Practices (Fall 99, 00, 01 and 02). [Course I]. A 3- units course in Electrical & Computer Engineering. The course is geared towards the needs of electrical, mechanical, reliability, biomedical, and structural engineers. Students come from leading San Diego and Irvine area firms such as Qualcomm, Kyocera, SAIC, Alaris, Honeywell, General Dynamics, General Atomics, OMM, BAE Systems and the Navy. Reviewed four times in a row by students as “very knowledgeable, excellent instructor”.