Freedom on the Net 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jawar Mohammed Biography: the Interesting Profile of an Influential Man

Jawar Mohammed Biography: The Interesting Profile of an Influential Man Jawar Mohammed is the energetic, dynamic and controversial political face of the majority of young Ethiopian Oromo’s, who now have been given the green light to freely participate in the country’s changing political scene. It is evident that he now has a wide reaching network that spans across continents, namely, the Americas, Europe, and obviously Africa. Jawar has perfected the art of disseminating his views to reach his massive audience base through the expert use of the many media outlets, some of which he runs. His OMN (Oromia Media Network) was a constant source of information for those hoping to hear and watch the news from a TV broadcast that was not associated with the government. Furthermore, Jawar’s handling of Facebook with a following of no less than 1.2 million people, as well as, his skillful use of various other social media tools has helped firmly place him as an important and influential leader in today's ever changing Ethiopian political landscape. Jawar Mohammed: Childhood Jawar Mohammed was born in Dumuga (Dhummugaa), a small and quiet rural town located on the border of Hararghe and Arsi within the Oromia region of Ethiopia. His parents were considered to be one of the first in the area to have an inter-religious marriage. Some estimates claim that Dumuga, is largely an Islamic town, with over 90% of the population adhering to the Muslim faith. His father being a Muslim opted to marry a Christian woman, thereby; the young couple destroyed one of the age old social norms and customs in Dumuga. -

Ethiopia’S Standing As Strategy and Commercial One of the Fastest Growing Economies in the World

E THIOPIA: A NEW DAWN? J UNE 8, 2018 SUMMARY ABOUT ASG • As the first member of the Oromo ethnic group to serve as Prime Minister, Abiy Albright Stonebridge Group Ahmed, only 41 years old, faces the dual challenges of building national (ASG) is the premier global reconciliation while pursuing economic policies to sustain Ethiopia’s standing as strategy and commercial one of the fastest growing economies in the world. He’s off to a strong start. diplomacy firm. We help clients understand and • The new prime minister’s first efforts at reconciliation and reform appear to have successfully navigate the calmed much of the social unrest which marred the final years of the tenure of intersection of public, private, and social sectors in former Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn. The state of emergency the international markets. government had imposed in the face the unrest was lifted two months ahead of ASG’s worldwide team has schedule. served clients in more than 110 countries. • The Ethiopian government has focused on transforming the country into one of Africa’s manufacturing hubs by developing infrastructure and sector-specific ALBRIGHTSTONEBRIDGE.COM industrial parks. These industrial zones have attracted a good amount of foreign direct investment (FDI), primarily from China, India, and Turkey. U.S. companies are also present. • This month, the government announced the privatization of state-owned enterprises, including the telecommunication and airline sectors. Successful implementation of these efforts, coupled with resolution of the issue of foreign exchange shortages, would increase Ethiopia’s attractiveness as a FDI destination and boost its economic growth rate. -

The Internet and Regulatory Responses in Ethiopia: Telecoms, Cybercrimes, Privacy, E-Commerce, and the New Media

The Internet and Regulatory Responses in Ethiopia: Telecoms, Cybercrimes, Privacy, E-commerce, and the New Media Kinfe Micheal Yilma . and Halefom Hailu Abraha.. Abstract Whilst Ethiopia has telephone services since 1894 − not long after its invention−, the history of the Internet in Ethiopia is less than two decades old. The prototype Internet with limited accessibility was introduced only in 1997, and broadband Internet was not widely deployed until recently. This slow pace in the proliferation of the Internet has delayed the legislative responses of the country to the brave new worlds of the Internet. Despite a few laws currently in operation namely the cybercrime and telecom fraud offence laws, most areas of the online environment needs the attention of the Ethiopian legislature. Nonetheless, there are few draft cyber laws that are in the pipeline. This article briefly reviews major legislative developments in telecoms, cybercrime, privacy, e-commerce and the new media. It sketches legislative responses of the Ethiopian legislature to the advent of the Internet by outlining major sources of Internet law and their defining features. The article further considers the salient features of the major draft pieces of cyber legislation that await enactment. Key terms Internet, information technology, telecommunications, cyber law, Internet law, e-commerce, Ethiopia DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mlr.v9i1.4 Acronyms CA Certification Authority DESL Draft Electronic Signature Law DETL Draft Electronic Transactions Law DoS Denial of Service Attacks . Kinfe Micheal Yilma (LLB, Addis Ababa University; LLM, University of Oslo; LLM, Brunel University London). The author was formerly a Lecturer-in-Law at Hawassa University. -

Human Rights Violations in Ethiopia

/ w / %w '* v *')( /)( )% +6/& $FOUFSGPS*OUFSOBUJPOBM)VNBO3JHIUT-BX"EWPDBDZ 6OJWFSTJUZPG8ZPNJOH$PMMFHFPG-BX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by University of Wyoming College of Law students participating in the Fall 2017 Human Rights Practicum: Jennie Boulerice, Catherine Di Santo, Emily Madden, Brie Richardson, and Gabriela Sala. The students were supervised and the report was edited by Professor Noah Novogrodsky, Carl M. Williams Professor of Law and Ethics and Director the Center for Human Rights Law & Advocacy (CIHRLA), and Adam Severson, Robert J. Golten Fellow of International Human Rights. The team gives special thanks to Julia Brower and Mark Clifford of Covington & Burling LLP for drafting the section of the report addressing LGBT rights, and for their valuable comments and edits to other sections. We also thank human rights experts from Human Rights Watch, the United States Department of State, and the United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office for sharing their time and expertise. Finally, we are grateful to Ethiopian human rights advocates inside and outside Ethiopia for sharing their knowledge and experience, and for the courage with which they continue to document and challenge human rights abuses in Ethiopia. 1 DIVIDE, DEVELOP, AND RULE: HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN ETHIOPIA CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW & ADVOCACY UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING COLLEGE OF LAW 1. PURPOSE, SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY 3 2. INTRODUCTION 3 3. POLITICAL DISSENTERS 7 3.1. CIVIC AND POLITICAL SPACE 7 3.1.1. Elections 8 3.1.2. Laws Targeting Dissent 14 3.1.2.1. Charities and Society Proclamation 14 3.1.2.2. Anti-Terrorism Proclamation 17 3.1.2.3. -

Invest in Ethiopia: Focus MEKELLE December 2012 INVEST in ETHIOPIA: FOCUS MEKELLE

Mekelle Invest in Ethiopia: Focus MEKELLE December 2012 INVEST IN ETHIOPIA: FOCUS MEKELLE December 2012 Millennium Cities Initiative, The Earth Institute Columbia University New York, 2012 DISCLAIMER This publication is for informational This publication does not constitute an purposes only and is meant to be purely offer, solicitation, or recommendation for educational. While our objective is to the sale or purchase of any security, provide useful, general information, product, or service. Information, opinions the Millennium Cities Initiative and other and views contained in this publication participants to this publication make no should not be treated as investment, representations or assurances as to the tax or legal advice. Before making any accuracy, completeness, or timeliness decision or taking any action, you should of the information. The information is consult a professional advisor who has provided without warranty of any kind, been informed of all facts relevant to express or implied. your particular circumstances. Invest in Ethiopia: Focus Mekelle © Columbia University, 2012. All rights reserved. Printed in Canada. ii PREFACE Ethiopia, along with 189 other countries, The challenges that potential investors adopted the Millennium Declaration in would face are described along with the 2000, which set out the millennium devel- opportunities they may be missing if they opment goals (MDGs) to be achieved by ignore Mekelle. 2015. The MDG process is spearheaded in Ethiopia by the Ministry of Finance and The Guide is intended to make Mekelle Economic Development. and what Mekelle has to offer better known to investors worldwide. Although This Guide is part of the Millennium effort we have had the foreign investor primarily and was prepared by the Millennium Cities in mind, we believe that the Guide will be Initiative (MCI), which is an initiative of of use to domestic investors in Ethiopia as The Earth Institute at Columbia University, well. -

A Survey of ICT Access and Usage in Ethiopia

ICT POLICY BRIEF NO.1 A Survey of ICT Access and Usage in Ethiopia: Policy Implications Executive Summary This policy brief presents a synthesis of the results of household survey on ICT access and usage that was conducted in Ethiopia and other 16 African countries at the end of 2007 and the beginning of 2008. The data were collected from a national sample of 2100 households. The survey covered 84 Enumeration Areas (EA) that were randomly selected based on the data available from the Central Statistics Agency. Major urban, urban and rural areas from Tigray, Amhara, SNNPR, Somali, Afar, Benshangul Gumuz, Oromiya, Hareri, Dire Dawa and Addis Ababa regions were covered to provide an overall picture of the state of ICT access and usage in the country. The paper synthesises the results of the ICT access and usage survey in comparison to other African countries and provides policy recommendations for actions. households that dwell in the same compounds; that has 1. Introduction inflated the figure slightly. Notwithstanding the relatively The Government of Ethiopia has made a significant progress high level of penetration, there is still a long way to go in in increasing access to the ICT in the recent years. The fixed bridging the access gap to fixed line network in the country, line penetration has reached 1.2% with mobile penetration in particular in rural areas. well above 3% in 2008. Progress was also made in the rural access front, particularly in connecting rural towns that did not have access to modern information and communication technologies. The incumbent’s (Ethiopian Telecommunica‐ tions Corporation) stations were expanded to 936 places mostly in rural towns. -

Ethiopia COI Compilation

BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Ethiopia: COI Compilation November 2019 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord This report was commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Background information ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Geographical information .................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Map of Ethiopia ........................................................................................................... -

Ethiopia Signs Mobile Expansion Deal with China's ZTE 19 August 2013

Ethiopia signs mobile expansion deal with China's ZTE 19 August 2013 the capital Addis Ababa. Ethio Telecom, the country's only phone and Internet provider, aims to increase mobile coverage to 80 percent of Ethiopia with the expansion project. Andualem said the expansion is part of Ethiopia's "growth and transformation plan," an economic blueprint that aims to boost growth and help Ethiopia reach middle-income status by 2025. Less than one percent of Ethiopia's 85 million people have access to mobile Internet and 23 percent of its population subscribe to mobile Mobile devices are displayed on a ZTE sales counter in phones, according to the International Wuhan, central China's Hubei province on October 8, Telecommunications Union (ITU). 2012. Ethiopia signed an $800-million (600-million-euro) agreement with Chinese telecom giant ZTE Sunday to © 2013 AFP expand its telecommunications network, national operator Ethio Telecom said. Ethiopia signed an $800-million (600-million-euro) agreement with Chinese telecom giant ZTE Sunday to expand its telecommunications network, national operator Ethio Telecom said. "The expansion project is vital to attain Ethio Telecom's objective of increasing telecoms service access and coverage across the nation as well as to upgrade the existing network," chief executive Andualem Admassie told reporters at a signing ceremony. The agreement is part of a telecommunications expansion project worth $1.6 billion, which is shared with China's Huawei Technologies. Huawei and ZTE have split the cost of the scheme. The expansion project aims to increase mobile phone and 3G Internet access throughout the country and introduce 4G broadband Internet in 1 / 2 APA citation: Ethiopia signs mobile expansion deal with China's ZTE (2013, August 19) retrieved 1 October 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2013-08-ethiopia-mobile-expansion-china-zte.html This document is subject to copyright. -

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: the Political Situation

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: The political situation Conducted 16 September 2019 to 20 September 2019 Published 10 February 2020 This project is partly funded by the EU Asylum, Migration Contentsand Integration Fund. Making management of migration flows more efficient across the European Union. Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 5 Background ............................................................................................................ 5 Purpose of the mission ........................................................................................... 5 Report’s structure ................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 6 Identification of sources .......................................................................................... 6 Arranging and conducting interviews ...................................................................... 6 Notes of interviews/meetings .................................................................................. 7 List of abbreviations ................................................................................................ 8 Executive summary .................................................................................................. 9 Synthesis of notes ................................................................................................ -

Rethinking Ethiopia

RETHINKING ETHIOPIA With the world’s help, one of Africa’s rising stars is changing perceptions, making progress, and fulfilling its potential, despite tough challenges ETHIOPIA IN FIGURES 9 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, more than any other African nation n times of economic uncertainty, “By 2025, Ethiopia will be Home to around 100 million, 13 months in every year, Inations tend to focus on a middle-income economy Ethiopia has slashed poverty levels according to Ethiopia’s Julian domestic concerns and lose sight of with zero net growth in from 39% in 2004 to be on target for calendar issues of global importance. This carbon emissions” 22.2% by the end of last year. It has 80 ethnic groups that make March, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister, Hailemariam Desalegn, Prime Minister also made major strides towards its up the nation’s population Hailemariam Desalegn, called on Millennium Development Goals, 85 percentage of water the world not to forget his country one of the world’s fastest growing reducing child mortality, rolling out supplied to the Nile River as it faces its worst drought in 50 economies over the past decade primary education, doubling access 200 dialects spoken years, which has put more than 10 and secured significant human to drinking water in just five years, throughout the country million people at risk of famine development gains. According to the and extending its Productive Safety 597 estimated GDP per and could erode the remarkable World Bank, it boasts ‘strong, broad- Net Program to cover eight million capita, in US$, in 2015 (IMF) achievements Ethiopia has made based growth’, expanding by a mean vulnerable citizens. -

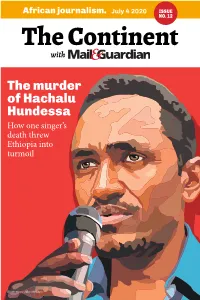

The Continent ISSUE 12

African journalism. July 4 2020 ISSUE NO. 12 The Continent with The murder of Hachalu Hundessa How one singer’s death threw Ethiopia into turmoil Illustration: John McCann Graphic: JOHN McCANN The Continent Page 2 ISSUE 12. July 4 2020 Editorial Abiy Ahmed’s greatest test When Abiy Ahmed became prime accompanying economic crisis, from minister of Ethiopia in 2018, he made which Ethiopia is not spared. the job look easy. Within months, he had released thousands of political All this occurs against prisoners; unbanned independent media and opposition groups; fired officials the backdrop of the implicated in human rights abuses; and global pandemic and made peace with neighbouring Eritrea. the accompanying Last year, he was rewarded with the economic crisis Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his efforts in brokering that peace. But the job of prime minister is never The future of 109-million Ethiopians easy, and now Abiy faces two of his now depends on what Abiy and his sternest tests – simultaneously. administration do next. The internet With the rainy season approaching, and information blackout imposed this Ethiopia is about to start filling the week, along with multiple reports of Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam brutality from state security forces and on the Blue Nile. No deal has been the arrests of key opposition leaders, are concluded with Egypt and Sudan, who a worrying sign that the government are both totally reliant on the waters of is resorting to repression to maintain the Nile River, and regional tensions are control. rising fast. Prime Minister Abiy was more than And then, this week, the assassination happy to accept the Nobel Peace Prize of Hachalu Hundessa (p15), an iconic last year, even though that peace deal singer and activist, sparked a wave of with Eritrea had yet to be tested (its key intercommunal conflict and violent provisions remain unfulfilled by either protests that threatens to upend side). -

Analysis of Account Receivables and Payment Defaults in Ethio Telecom with Reference to Mekelle Branch, Ethiopia Mohan.M.P Asst.Professor, Dept

G.J.I.S.S.,Vol.2(6):1-11 (November-December, 2013) ISSN: 2319-8834 Analysis of Account Receivables and Payment defaults in Ethio Telecom with reference to Mekelle Branch, Ethiopia Mohan.M.P Asst.Professor, Dept. Accounting and Finance, Adigrat University, Ethiopia. Abstract The starting period of the Telecommunication Industry in Ethiopia goes back to the reign of Emperor Menilik in 1894, during the construction of the capital city, Addis Ababa. This was followed by the Inter urban network construction to connect many important centre of the empire by 1930. Ethiopian telecommunication joined ITU (International Telecommunication Union) in 1932 and was showing good progress in the area until the Italian Acceptation. During 1932 – 1942 the network was seriously damaged because of the consecutive wars. Currently, the state monopolyTelecommunication service provider in Ethiopia, Ethiopian TelecommunicationsCorporations re-born on December2, 2010 as Ethio-Telecom after France Telecom takes themanagement contract. The company maintains proper records of the receivables by strictly following the credit policies. It grants a total of 45 days credit to the subscribers. The credit payment system is mainly allowed to Government Organizations and NGOs. Key words: Account receivables, Trend analysis, Ratio Analysis. Introduction Background of the study From the employee point of view, pay is a necessity in life. Few people are so wealthy they do how not accept financial remuneration for there work. The compensation received for work is one the chief reason people seeks employment. Pay is the means by which employees satisfy their own and their family needs. Compensation may be the only (or certainly reward factor) to their effort.