Uluslararası İnsan Bilimleri Dergisi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

519 Ethiopia Report With

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Ethiopia: A New Start? T • ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY KJETIL TRONVOLL ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully © Minority Rights Group 2000 acknowledges the support of Bilance, Community Aid All rights reserved Abroad, Dan Church Aid, Government of Norway, ICCO Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- and all other organizations and individuals who gave commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- financial and other assistance for this Report. mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. For further information please contact MRG. This Report has been commissioned and is published by A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the ISBN 1 897 693 33 8 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the ISSN 0305 6252 author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in Published April 2000 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. Typset by Texture Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Tadesse Tafesse (Programme Coordinator) and Katrina Payne (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR KJETIL TRONVOLL is a Research Fellow and Horn of Ethiopian elections for the Constituent Assembly in 1994, Africa Programme Director at the Norwegian Institute of and the Federal and Regional Assemblies in 1995. -

Findet Äthiopien Wege Aus Der Krise? Die Folgenden Quellen Wurden in Dem Heft Verwendet (Originale Teilweise Geringfügig Gekürzt)

DEUTSCH-ÄTHIOPISCHER VEREIN E.V. GERMAN ETHIOPIAN ASSOCIATION INFORMATIONSBLÄTTER 3/2017 Findet Äthiopien Wege aus der Krise? Die folgenden Quellen wurden in dem Heft verwendet (Originale teilweise geringfügig gekürzt) Political unrest simmering in Ethiopia ………………………………………………………… 1 Merga Yonas Bula, Deutsche Welle, 10.2.2017 Opposition parties to negotiate with EPRDF in unison ……………………………………. 3 Ethiopian News Agency ENA, 9.2.2017 Timely Ethiopian teachers’ warning against TPLF divisiveness …………………………. 3 Ethiopia Observatory, 9.2.2017 Public ultimate guarantor of nation’s peace and security ………………………………… 4 Ethiopian Reporter, Editorial, 4.2.2017 Ethiopia: A Gathering Political Storm ………………………………………………………… 5 Alem Mamo, Nazret.com 1.2.2017 Ethiopia claims success in quashing wave of anti-government unrest ………………… 6 John Aglionby, Financial Times in Addis Ababa, 1.2.2017 Ethiopia: The Slow Death of a Civilian Government and the Rise of a Military Might … 7 Addis Standard, 24.1.2017 A Wish List for Successful Opposition and Government Negotiations ……………….. 11 Solomon Gebreselassie, Ethiopian Observer, 22.1.2017 Salvaging Political Pluralism ………………………………………………………………….. 13 Asrat Seyoum, Ethiopian Reporter, 21.1.2017 Analysis: Inside the controversial EFFORT ………………………………………………. 14 Oman Uliah, Special to Addis Standard, 16.1.2017 Ethiopia: Justified Fears ………………………………………………………………………. 18 Desta Heliso, Nazret.com, 30.12.2016 Ethiopia in the eyes of a veteran scholar ………………………………………………….. 20 Ethiopian Reporter, 17.12.2016, Interview by Tibebeselassie Feeling the Pulse of the People ……………………………………………………………… 24 Ethiopian Reporter, Editorial, 10 Dec 2016, by Staff Reporter Ethiopia at a crossroads as it feels the strain of civil unrest ………………………….. 26 James Jeffrey, Irish Times, Addis Ababa, 9 December 2016 New television channels in Ethiopia may threaten state control ………………………. -

The Internet and Regulatory Responses in Ethiopia: Telecoms, Cybercrimes, Privacy, E-Commerce, and the New Media

The Internet and Regulatory Responses in Ethiopia: Telecoms, Cybercrimes, Privacy, E-commerce, and the New Media Kinfe Micheal Yilma . and Halefom Hailu Abraha.. Abstract Whilst Ethiopia has telephone services since 1894 − not long after its invention−, the history of the Internet in Ethiopia is less than two decades old. The prototype Internet with limited accessibility was introduced only in 1997, and broadband Internet was not widely deployed until recently. This slow pace in the proliferation of the Internet has delayed the legislative responses of the country to the brave new worlds of the Internet. Despite a few laws currently in operation namely the cybercrime and telecom fraud offence laws, most areas of the online environment needs the attention of the Ethiopian legislature. Nonetheless, there are few draft cyber laws that are in the pipeline. This article briefly reviews major legislative developments in telecoms, cybercrime, privacy, e-commerce and the new media. It sketches legislative responses of the Ethiopian legislature to the advent of the Internet by outlining major sources of Internet law and their defining features. The article further considers the salient features of the major draft pieces of cyber legislation that await enactment. Key terms Internet, information technology, telecommunications, cyber law, Internet law, e-commerce, Ethiopia DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mlr.v9i1.4 Acronyms CA Certification Authority DESL Draft Electronic Signature Law DETL Draft Electronic Transactions Law DoS Denial of Service Attacks . Kinfe Micheal Yilma (LLB, Addis Ababa University; LLM, University of Oslo; LLM, Brunel University London). The author was formerly a Lecturer-in-Law at Hawassa University. -

Ethiopia, the TPLF and Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor Paulos Milkias Marianopolis College/Concordia University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks at WMU Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU International Conference on African Development Center for African Development Policy Research Archives 8-2001 Ethiopia, The TPLF and Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor Paulos Milkias Marianopolis College/Concordia University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/africancenter_icad_archive Part of the African Studies Commons, and the Economics Commons WMU ScholarWorks Citation Milkias, Paulos, "Ethiopia, The TPLF nda Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor" (2001). International Conference on African Development Archives. Paper 4. http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/africancenter_icad_archive/4 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for African Development Policy Research at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conference on African Development Archives by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ETHIOPIA, TPLF AND ROOTS OF THE 2001 * POLITICAL TREMOR ** Paulos Milkias Ph.D. ©2001 Marianopolis College/Concordia University he TPLF has its roots in Marxist oriented Tigray University Students' movement organized at Haile Selassie University in 1974 under the name “Mahber Gesgesti Behere Tigray,” [generally T known by its acronym – MAGEBT, which stands for ‘Progressive Tigray Peoples' Movement’.] 1 The founders claim that even though the movement was tactically designed to be nationalistic it was, strategically, pan-Ethiopian. 2 The primary structural document the movement produced in the late 70’s, however, shows it to be Tigrayan nationalist and not Ethiopian oriented in its content. -

Human Rights Violations in Ethiopia

/ w / %w '* v *')( /)( )% +6/& $FOUFSGPS*OUFSOBUJPOBM)VNBO3JHIUT-BX"EWPDBDZ 6OJWFSTJUZPG8ZPNJOH$PMMFHFPG-BX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by University of Wyoming College of Law students participating in the Fall 2017 Human Rights Practicum: Jennie Boulerice, Catherine Di Santo, Emily Madden, Brie Richardson, and Gabriela Sala. The students were supervised and the report was edited by Professor Noah Novogrodsky, Carl M. Williams Professor of Law and Ethics and Director the Center for Human Rights Law & Advocacy (CIHRLA), and Adam Severson, Robert J. Golten Fellow of International Human Rights. The team gives special thanks to Julia Brower and Mark Clifford of Covington & Burling LLP for drafting the section of the report addressing LGBT rights, and for their valuable comments and edits to other sections. We also thank human rights experts from Human Rights Watch, the United States Department of State, and the United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office for sharing their time and expertise. Finally, we are grateful to Ethiopian human rights advocates inside and outside Ethiopia for sharing their knowledge and experience, and for the courage with which they continue to document and challenge human rights abuses in Ethiopia. 1 DIVIDE, DEVELOP, AND RULE: HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN ETHIOPIA CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW & ADVOCACY UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING COLLEGE OF LAW 1. PURPOSE, SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY 3 2. INTRODUCTION 3 3. POLITICAL DISSENTERS 7 3.1. CIVIC AND POLITICAL SPACE 7 3.1.1. Elections 8 3.1.2. Laws Targeting Dissent 14 3.1.2.1. Charities and Society Proclamation 14 3.1.2.2. Anti-Terrorism Proclamation 17 3.1.2.3. -

A Survey of ICT Access and Usage in Ethiopia

ICT POLICY BRIEF NO.1 A Survey of ICT Access and Usage in Ethiopia: Policy Implications Executive Summary This policy brief presents a synthesis of the results of household survey on ICT access and usage that was conducted in Ethiopia and other 16 African countries at the end of 2007 and the beginning of 2008. The data were collected from a national sample of 2100 households. The survey covered 84 Enumeration Areas (EA) that were randomly selected based on the data available from the Central Statistics Agency. Major urban, urban and rural areas from Tigray, Amhara, SNNPR, Somali, Afar, Benshangul Gumuz, Oromiya, Hareri, Dire Dawa and Addis Ababa regions were covered to provide an overall picture of the state of ICT access and usage in the country. The paper synthesises the results of the ICT access and usage survey in comparison to other African countries and provides policy recommendations for actions. households that dwell in the same compounds; that has 1. Introduction inflated the figure slightly. Notwithstanding the relatively The Government of Ethiopia has made a significant progress high level of penetration, there is still a long way to go in in increasing access to the ICT in the recent years. The fixed bridging the access gap to fixed line network in the country, line penetration has reached 1.2% with mobile penetration in particular in rural areas. well above 3% in 2008. Progress was also made in the rural access front, particularly in connecting rural towns that did not have access to modern information and communication technologies. The incumbent’s (Ethiopian Telecommunica‐ tions Corporation) stations were expanded to 936 places mostly in rural towns. -

Ethiopia: Ethnic Federalism and Its Discontents

ETHIOPIA: ETHNIC FEDERALISM AND ITS DISCONTENTS Africa Report N°153 – 4 September 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. FEDERALISING THE POLITY..................................................................................... 2 A. THE IMPERIAL PERIOD (-1974) ....................................................................................................2 B. THE DERG (1974-1991)...............................................................................................................3 C. FROM THE TRANSITIONAL GOVERNMENT TO THE FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC (1991-1994)...............................................................................................................4 III. STATE-LED DEMOCRATISATION............................................................................. 5 A. AUTHORITARIAN LEGACIES .........................................................................................................6 B. EVOLUTION OF MULTIPARTY POLITICS ........................................................................................7 1. Elections without competition .....................................................................................................7 2. The 2005 elections .......................................................................................................................8 -

Development Without Freedom RIGHTS How Aid Underwrites Repression in Ethiopia WATCH

Ethiopia HUMAN Development without Freedom RIGHTS How Aid Underwrites Repression in Ethiopia WATCH Development without Freedom How Aid Underwrites Repression in Ethiopia Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-697-7 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org October 2010 1-56432-697-7 Development without Freedom How Aid Underwrites Repression in Ethiopia Map of Ethiopia .................................................................................................................. 1 Glossary of Abbreviations .................................................................................................. 2 Summary ........................................................................................................................... 4 Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 8 To the Government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia ................................. 8 To Ethiopia’s Principal Foreign Donors in the Development Assistance Group ................ -

Ethiopia COI Compilation

BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Ethiopia: COI Compilation November 2019 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord This report was commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Background information ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Geographical information .................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Map of Ethiopia ........................................................................................................... -

ETHIOPIA Ethiopia Is a Federal Republic Led by Prime

ETHIOPIA Ethiopia is a federal republic led by Prime Minister Meles Zenawi and the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). The population is estimated at 82 million. In the May national parliamentary elections, the EPRDF and affiliated parties won 545 of 547 seats to remain in power for a fourth consecutive five-year term. In simultaneous elections for regional parliaments, the EPRDF and its affiliates won 1,903 of 1,904 seats. In local and by-elections held in 2008, the EPRDF and its affiliates won all but four of 3.4 million contested seats after the opposition parties, citing electoral mismanagement, removed themselves from the balloting. Although there are more than 90 ostensibly opposition parties, which carried 21 percent of the vote nationwide in May, the EPRDF and its affiliates, in a first-past-the-post electoral system, won more than 99 percent of all seats at all levels. Although the relatively few international officials that were allowed to observe the elections concluded that technical aspects of the vote were handled competently, some also noted that an environment conducive to free and fair elections was not in place prior to election day. Several laws, regulations, and procedures implemented since the 2005 national elections created a clear advantage for the EPRDF throughout the electoral process. Political parties were predominantly ethnically based, and opposition parties remained splintered. During the year fighting between government forces, including local militias, and the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), an ethnically based, violent insurgent movement operating in the Somali region, resulted in continued allegations of human rights abuses by all parties to the conflict. -

Trends and Spatio-Temporal Variation of Female

Tesema et al. BMC Public Health (2020) 20:719 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08882-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Trends and Spatio-temporal variation of female genital mutilation among reproductive-age women in Ethiopia: a Spatio-temporal and multivariate decomposition analysis of Ethiopian demographic and health surveys Getayeneh Antehunegn Tesema1*, Chilot Desta Agegnehu2, Achamyeleh Birhanu Teshale1, Adugnaw Zeleke Alem1, Alemneh Mekuriaw Liyew1, Yigizie Yeshaw3 and Sewnet Adem Kebede1 Abstract Background: Female genital mutilation (FGM) is a serious health problem globally with various health, social and psychological consequences for women. In Ethiopia, the prevalence of female genital mutilation varied across different regions of the country. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the trend and determinants of female genital mutilation among reproductive-age women over time. Methods: A secondary data analysis was done using 2000, 2005, and 2016 Demographic Health Surveys (DHSs) of Ethiopia. A total weighted sample of 36,685 reproductive-age women was included for analysis from these three EDHS Surveys. Logit based multivariate decomposition analysis was employed for identifying factors contributing to the decrease in FGM over time. The Bernoulli model was fitted using spatial scan statistics version 9.6 to identify hotspot areas of FGM, and ArcGIS version 10.6 was applied to explore the spatial distribution FGM across the country. (Continued on next page) * Correspondence: [email protected] 1Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Institute of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia Full list of author information is available at the end of the article © The Author(s). -

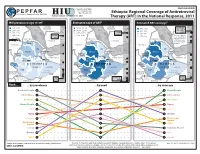

Ethiopia: Regional Coverage of Antiretroviral U.S

U.S. Department of State UNCLASSIFIED [email protected] PEPFAR http://hiu.state.gov Ethiopia: Regional Coverage of Antiretroviral U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief HUMANITARIAN INFORMATION UNIT Therapy (ART) in the National Response, 2011 HIV prevalence (age 15-49)1 Estimated need of ART2 Estimated ART coverage2 SAUDI Percent SAUDI In Percent 5.0% - 6.5% ARABIA 54,000 - 110,000 ARABIA thousands 80% or more Harari People, 2.0% - 4.9% Red 31,000 - 53,000 Red Red Addis Ababa* 110 50% - 79% >95% 1.5% - 1.9% Sea 7% 9,800 - 30,000 Sea Oromia Sea 100% 108,485 30% -49% 0.9% - 1.4% Gambela 1,900 - 9,700 29% or less *Coverage appears 6.5% to exceed estimated 0 100 200 km regional need due ERITREA 6 ERITREA ERITREA to ART provision to YEMEN YEMEN 90 0 100 200 mi clients from outside 80 Tigray Tigray Tigray the region. SUDAN SUDAN SUDAN 5 Afar Gulf of Afar Gulf of Afar Gulf of Aden Aden 70 Aden Amhara DJIBOUTI Amhara DJIBOUTI Amhara DJIBOUTI 60 Binshangul 4 Binshangul Binshangul Gumuz Dire Dawa Gumuz Dire Dawa Gumuz Dire Dawa SOMALIA SOMALIA SOMALIA Addis Harari Addis Harari 50 Addis Harari Ababa 3 Ababa Ababa People People People 40 Gambela ETHIOPIA Gambela ETHIOPIA Gambela ETHIOPIA People People People Oromia Somali Oromia Somali Oromia Somali 2 30 SNNP Provisional SNNP Provisional SNNP Provisional SOUTH administrative SOUTH administrative SOUTH administrative 20 SUDAN line SUDAN line SUDAN line 1 Somali Administrative SNNP Administrative Harari People 10 Administrative boundary 0.9% boundary 1,879 boundary 10% KENYA KENYA KENYA Rank ..