Centering Prayer and Attention of the Heart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

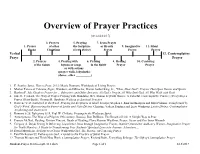

Overview of Prayer Practices

Overview of Prayer Practices (revised 4/2/17) 3. Prayers 5. Praying 7. Jesus Prayer 1. Prayer of other the Scripture or Breath 9. Imaginative 11. Silent Books Christians (lectio divina) Prayer Prayer Prayer Verbal 12. Contemplative Praye Prayer 2. Prayers 4. Praying with 6. Praying 8. Healing 10. Centering of the Saints hymns or songs in the Spirit Prayer Prayer or with actions (prayer walk, labyrinth,) (dance, other __________) 1. E. Stanley Jones, How to Pray, 2015; Maxie Dunnam, Workbook of Living Prayer; 2. Mother Teresa of Calcutta, Signs, Wonders, and Miracles; Martin Luther King, Jr., "Thou, Dear God": Prayers That Open Hearts and Spirits 3. Rueben P. Job, Guide to Prayer for ... (Ministers and Other Servants, All God’s People, All Who Seek God, All Who Walk with God) 4. Jane E. Vennard, The Way of Prayer; Praying with Mandalas; Rev. Sharon Seyfarth Garner, A Colorful, Contemplative Practice; Every Step a Prayer (Print Book); Thomas R. Hawkins, Walking as Spiritual Practice 5. Norvene Vest, Gathered in the Word: Praying the Scriptures in Small Groups; Stephen J. Binz and Kaspars and Ruta Poikans, Transformed by God’s Word: Discovering the Power of Lectio and Visio Divina; Christine Valters Paintner and Lucy Wynkoop, Lectio Divina: Contemplative Awakening and Awareness 6. Romans 8:26, Ephesians 6:18, Paul W. Chilcote, Praying in the Wesleyan Spirit 7. Annonymous, The Way of a Pilgrim(19th century, Russia); Ron DelBene, The Breath of Life: A Simple Way to Pray 8. Francis McNutt, Healing; Kristen Vincent, Beads of Healing; Flora Slosson Wuellner, Prayer, Stress and Our Inner Wounds 9. -

Nil Sorsky: the Authentic Writings Early 18Th Century Miniature of Nil Sorsky and His Skete (State Historical Museum Moscow, Uvarov Collection, No

CISTER C IAN STUDIES SERIES : N UMBER T WO HUNDRED T WENTY -ONE David M. Goldfrank Nil Sorsky: The Authentic Writings Early 18th century miniature of Nil Sorsky and his skete (State Historical Museum Moscow, Uvarov Collection, No. 107. B 1?). CISTER C IAN STUDIES SERIES : N UMBER T WO H UNDRED TWENTY -ONE Nil Sorsky: The Authentic Writings translated, edited, and introduced by David M. Goldfrank Cistercian Publications Kalamazoo, Michigan © Translation and Introduction, David M. Goldfrank, 2008 The work of Cistercian Publications is made possible in part by support from Western Michigan University to The Institute of Cistercian Studies Nil Sorsky, 1433/1434-1508 Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Nil, Sorskii, Saint, ca. 1433–1508. [Works. English. 2008] Nil Sorsky : the authentic writings / translated, edited, and introduced by David M. Goldfrank. p. cm.—(Cistercian studies series ; no. 221) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN 978-0-87907-321-3 (pbk.) 1. Spiritual life—Russkaia pravoslavnaia tserkov‚. 2. Monasticism and religious orders, Orthodox Eastern—Russia—Rules. 3. Nil, Sorskii, Saint, ca. 1433–1508—Correspondence. I. Goldfrank, David M. II. Title. III. Title: Authentic writings. BX597.N52A2 2008 248.4'819—dc22 2008008410 Printed in the United States of America ∆ Estivn ejn hJmi'n nohto;~ povlemo~ tou' aijsqhtou' calepwvtero~. ¿st; mysla rat;, vnas= samäx, h[v;stv÷nyã l[täi¡wi. — Philotheus the Sinaite — Within our very selves is a war of the mind fiercer than of the senses. Fk 2: 274; Eparkh. 344: 343v Table of Contents Author’s Preface xi Table of Bibliographic Abbreviations xvii Transliteration from Cyrillic Letters xx Technical Abbreviations in the Footnotes xxi Part I: Toward a Study of Nil Sorsky I. -

Consciousness of God As God Is: the Phenomenology of Christian Centering Prayer

CONSCIOUSNESS OF GOD AS GOD IS: THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF CHRISTIAN CENTERING PRAYER BY BENNO ALEXANDER BLASCHKE A dissertation submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington (2017) Abstract In this study I aim to give an alternative approach to the way we theorise in the philosophy and comparative study of mysticism. Specifically, I aim to shift debate on the phenomenal nature of contemplative states of consciousness away from textual sources and towards reliable and descriptively rich first-person data originating in contemporary practices of lived traditions. The heart of this dissertation lies in rich qualitative interview data obtained through recently developed second-person approaches in the science of consciousness. I conducted in-depth phenomenological interviews with 20 Centering Prayer teachers and practitioners. The interviews covered the larger trajectory of their contemplative paths and granular detail of the dynamics of recent seated prayer sessions. I aided my second-person method with a “radical participation” approach to fieldwork at St Benedict’s Monastery in Snowmass. In this study I present nuanced phenomenological analyses of the first-person data regarding the beginning to intermediate stages of the Christian contemplative path, as outlined by the Centering Prayer tradition and described by Centering Prayer contemplatives. My presentation of the phenomenology of Centering Prayer is guided by a synthetic map of Centering Prayer’s (Keating School) contemplative path and model of human consciousness, which is grounded in the first-person data obtained in this study and takes into account the tradition’s primary sources. -

Course Listing Hellenic College, Inc

jostrosky Course Listing Hellenic College, Inc. Academic Year 2020-2021 Spring Credit Course Course Title/Description Professor Days Dates Time Building-Room Hours Capacity Enrollment ANGK 3100 Athletics&Society in Ancient Greece Dr. Stamatia G. Dova 01/19/2105/14/21 TBA - 3.00 15 0 This course offers a comprehensive overview of athletic competitions in Ancient Greece, from the archaic to the hellenistic period. Through close readings of ancient sources and contemporary theoretical literature on sports and society, the course will explore the significance of athletics for ancient Greek civilization. Special emphasis will be placed on the Olympics as a Panhellenic cultural institution and on their reception in modern times. ARBC 6201 Intermediate Arabic I Rev. Edward W. Hughes R 01/19/2105/14/21 10:40 AM 12:00 PM TBA - 1.50 8 0 A focus on the vocabulary as found in Vespers and Orthros, and the Divine Liturgy. Prereq: Beginning Arabic I and II. ARTS 1115 The Museums of Boston TO BE ANNOUNCED 01/19/2105/14/21 TBA - 3.00 15 0 This course presents a survey of Western art and architecture from ancient civilizations through the Dutch Renaissance, including some of the major architectural and artistic works of Byzantium. The course will meet 3 hours per week in the classroom and will also include an additional four instructor-led visits to relevant area museums. ARTS 2163 Iconography I Mr. Albert Qose W 01/19/2105/14/21 06:30 PM 09:00 PM TBA - 3.00 10 0 This course will begin with the preparation of the board and continue with the basic technique of egg tempera painting and the varnishing of an icon. -

Centering Prayer, As in All Methods Leading to Contemplative Prayer, Is the Indwelling Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit

Theological Background The source of Centering Prayer, as in all methods leading to contemplative prayer, is the indwelling Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The focus of Centering Prayer is the deepening of our relationship with the living Christ. It tends to build communities of faith and bond the members Be still and know that I am God. together in mutual friendship and love. PSALM 46:10 The Root of Centering Prayer Listening to the word of God in Scripture (Lectio Divina) is a traditional way of cultivating friendship Contemplative Prayer with Christ. It is a way of listening to the texts of We may think of prayer as thoughts or feelings Scripture as if we were in conversation with Christ expressed in words. But this is only one expression. and he were suggesting the topics of conversation. The Method of In the Christian tradition contemplative prayer The daily encounter with Christ and reflection on For information and resources: is considered to be the pure gift of God. It is the his word leads beyond mere acquaintanceship to an opening of mind and heart - our whole being - attitude of friendship, trust, and love. Conversation Contemplative Outreach, Ltd. CENTERING to God, the Ultimate Mystery, beyond thoughts, simplifies and gives way to communing. Gregory 10 Park Place, 2nd Floor, Suite B words, and emotions. Through grace we open our the Great (6th century) in summarizing the Butler, NJ 07405 awareness to God whom we know by faith is within Christian contemplative tradition expressed it as PRAYER 973.838.3384 us, closer than breathing, closer than thinking, closer “resting in God.” This was the classical meaning of [email protected] THE PRAYER OF CONSENT than choosing, closer than consciousness itself. -

Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa

Durham E-Theses Language and theology in St Gregory of Nyssa Neamµu, Mihail G. How to cite: Neamµu, Mihail G. (2002) Language and theology in St Gregory of Nyssa, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4187/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk University of Durham Faculty of Arts Department of Theology The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa Mihail G. Neamtu St John's College September 2002 M.A. in Theological Research Supervisor: Prof Andrew Louth This dissertation is the product of my own work, and the work of others has been properly acknowledged throughout. Mihail Neamtu Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa MA (Research) Thesis, September 2002 Abstract This MA thesis focuses on the work of one of the most influential and authoritative theologians of the early Church: St Gregory of Nyssa (f396). -

Facilitator Handbook

Facilitator Handbook Serving Others on the Spiritual Journey in Community Publication Date – April 2019 © 2018. Contemplative Outreach Ltd. Butler, New Jersey. USA. All Rights Reserved. Facilitator Handbook – April 2019 Serving Others on the Spiritual Journey in Community Copyright 2019. All Rights Reserved. No portion of the material contained in this document may be copied or distributed without express written consent of Contemplative Outreach, Ltd. Contemplative Outreach, Ltd. 10 Park Place, 2nd Floor, Suite B, Butler, New Jersey 07405 973-838-3384 Fax 973-492-5795 www.contemplativeoutreach.org [email protected] © 2019. Contemplative Outreach, Ltd. All Rights Reserved. 2 Facilitator Handbook – April 2019 Serving Others on the Spiritual Journey in Community Acknowledgements Acknowledgement is gratefully made to Contemplative Outreach for permission to either reprint or edit excerpts from the online material. Edited 2013 for Contemplative Outreach by Bonnie J. Shimizu for use by all facilitators in the community of Contemplative Outreach. Edited 2018 by the Contemplative Outreach Facilitator Formation and Enrichment Service Team. Edited 2019 to update Service Team name from to Contemplative Outreach Facilitator Formation and Enrichment Service Team to Centering Prayer Group Facilitator Support Service Team. © 2019. Contemplative Outreach, Ltd. All Rights Reserved. 3 Facilitator Handbook – April 2019 Serving Others on the Spiritual Journey in Community Preface The purpose of this handbook is to provide structure, resources, and tools that a facilitator for a Centering Prayer group can use while supporting and empowering others on the spiritual journey. Typically, a Centering Prayer group is formed by persons who have an established prayer practice (or wish to establish one), often as a result of attending a Centering Prayer Introductory Program. -

1 Jerusalem and the Work of Discontinuity Elizabeth Key Fowden He Was Not Changing a Technique, but an Ontology. John Berger

Jerusalem and the Work of Discontinuity Elizabeth Key Fowden He was not changing a technique, but an ontology. John Berger, “Seker Ahmet and the Forest”1 In a review of Kamal Boullata’s 2009 book Palestinian Art: From 1850 to the Present, the critic Jean Fisher noted that “among Boullata’s most stunning insights . is that the crucible of Palestinian modernism is to be found in the Arabisation and progressive naturalisation of Byzantine iconography.”2 But Boullata himself did not follow this course. Instead, the Orthodox icon stimulated him to travel down a path away from the increasing naturalization of figural art toward varieties of abstraction, distilling the nonlinear perspective that lies at the existential heart of Orthodox iconography to create a modern artistic expression of a radically different sort from the Palestinian artists whose work he analyses in his book. Why did he take such a different path? Boullata has frequently observed that his own artistic impulse was first formed by three modes of artistic creation that coexisted in Jerusalem, where he was born and grew up: Byzantine icons, Arabic calligraphy, and Islamic ornament. He has not elaborated on the role of the Orthodox icon except to mention that his first lessons in painting were from the icon painter Khalil Halabi, who taught him to organize the multiple planes of an icon by the use of a grid. In his chapter “Peregrination Between Religious and Secular Painting,” Boullata also mentions “reverse perspective,” which he gleaned from the Byzantine art historian André Grabar, whose teacher in early twentieth-century St. -

Spiritual Struggle and Gregory of Nyssa's Theory of Perpetual Ascent

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-10-2019 Spiritual Struggle and Gregory of Nyssa’s Theory of Perpetual Ascent: An Orthodox Christian Virtue Ethic Stephen M. Meawad Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Ethics in Religion Commons Recommended Citation Meawad, S. M. (2019). Spiritual Struggle and Gregory of Nyssa’s Theory of Perpetual Ascent: An Orthodox Christian Virtue Ethic (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1768 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. SPIRITUAL STRUGGLE AND GREGORY OF NYSSA’S THEORY OF PERPETUAL ASCENT: AN ORTHODOX CHRISTIAN VIRTUE ETHIC A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Stephen M. Meawad May 2019 Copyright by Stephen Meawad 2019 SPIRITUAL STRUGGLE AND GREGORY OF NYSSA’S THEORY OF PERPETUAL ASCENT: AN ORTHODOX CHRISTIAN VIRTUE ETHIC By Stephen M. Meawad Approved December 14, 2018 _______________________________ _______________________________ Darlene F. Weaver, Ph.D. Elizabeth A. Cochran, Ph.D. Professor of Theology Associate Professor of Theology Director, Ctr for Catholic Intellectual Tradition Director of Graduate Studies (Committee Chair) (Committee Member – First Reader) _______________________________ _______________________________ Bogdan G. Bucur, Ph.D. Marinus C. Iwuchukwu, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Theology Associate Professor of Theology (Committee Member – Second Reader) Chair, Department of Theology Chair, Consortium Christian-Muslim Dial. -

Church Lectionary & Typicon Church Services and Events St John's

Saint John The Baptist Orthodox Church September 23, 2018 Church Lectionary & Typicon Seventeenth Sunday After Pentecost Sunday Before the Elevation of the Cross Virgin Martyrs Menodora, Metrodora, & Nymphodora Epistle : Galatians 6:11-18; Gospel : Mark3:13-27 St John The Baptist Orthodox Church Resurrectional Tone 8 1240 Broadbridge Ave Stratford, CT 06615 FIFTEENTH SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST www.sjoc.org Church Services and Events www.facebook.com/stjohns broadbridge The Venerable Poemen the Great Sunday, September 23 12:00PM Church Picnic Very Rev. Protopresbyter Peter Paproski Wednesday, September 26 Epistle : 2 Corinthians 4:6-15; [email protected] Gospel : Matthew 22: 35-48 6:30PM Great Vespers & Litya 7:30PM Adult Education Thursday, September 27 Office: 203-375-2564 Resurrectional Tone 6 Cell: 203-260-0423 9:00AM Divine Liturgy - Elevation of The Cross – Strict Fast Day _______________________ Saturday, September 29 Resurrectional Tone 5 9:00AM Pagachi Workshop A Parish of The American 5:00PM Great Vespers Carpatho-Russian Sunday, September 30 Resurrectional Tone 3 Orthodox Diocese 9:00AM Divine Liturgy 10:45AM Church School St John’s Stewards Diocesan Website: Date Coffee Hour Host Hours Epistle Church Cleaner http://www.acrod.org Sept 30 Decerbo Holly Bill Cleaning Service Camp Nazareth: http://www.campnazareth.org Oct 7 Ivers/Pierce Pani Carol Matt Cleaning Service Facebook: www.facebook.com/acroddiocese Twitter: 2018 Parish Stewardship Offering (As of 09/16 /18) https://twitter.com/acrodnews YTD: $48,209 .00 Goal: $70,000.00 You Tube: https://youtube.com/acroddiocese Announcements Lives of The CHURCH SCHOOL - The 2018-2019 Church School Year began last Sunday. -

The Centering Prayer Method by Thomas Keating, O.C.S.O

The Centering Prayer Method By Thomas Keating, O.C.S.O The following clarifications are in order concerning the Centering Prayer Method. 1. Centering Prayer is a traditional form of Christian prayer rooted in Scripture and based on the monastic heritage of “LectioDivina”. It is not to be confused with Transcendental Meditation or Hindu or Buddhist methods of meditation. It is not a New Age technique. Centering Prayer is rooted in the word of God, both in scripture and in the person of Jesus Christ. It is an effort to renew the Christian contemplative tradition handed down to us in an uninterrupted manner from St. Paul, who writes of the intimate knowledge of Christ that comes through love. Centering Prayer is designed to prepare sincere followers of Christ for contemplative prayer in the traditional sense in which spiritual writers understood that term for the first sixteen centuries of the Christian era. This tradition is summed up by St. Gregory the Great at the end of the sixth century. He describes contemplation as the knowledge of God impregnated with love. For Gregory, contemplation was the fruit of reflection on the word of God in Scripture as well as the precious gift of God. He calls it, "resting in God". In this “resting”, the mind and heart are not so much seeking God as beginning to experience, "to taste", what they have been seeking. This state is not the suspension of all activity, but the reduction of many acts and reflections into a single act or thought to sustain one's consent to God's presence and action. -

Ignatian and Hesychast Spirituality: Praying Together

St Vladimir’s Th eological Quarterly 59:1 (2015) 43–53 Ignatian and Hesychast Spirituality: Praying Together Tim Noble Some time aft er his work with St Makarios of Corinth (1731–1805) on the compilation of the Philokalia,1 St Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain (1748–1809) worked on a translation of an expanded version of the Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius Loyola.2 Metropolitan Kallistos Ware has plausibly suggested that the translation may have been motivated by Nikodimos’ intuition that there was something else needed to complement the hesychast tradition, even if only for those whose spiritual mastery was insuffi cient to deal with its demands.3 My interest in this article is to look at the encounters between the hesychast and Ignatian traditions. Clearly, when Nikodimos read Pinamonti’s version of Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises, he found in it something that was reconcilable with his own hesychast practice. What are these elements of agreement and how can two apparently quite distinct traditions be placed side by side? I begin my response with a brief introduction to the two traditions. I will also suggest that spiritual traditions off er the chance for experience to meet experience. Moreover, this experience is in principle available to all, though in practice the benefi ciaries will always be relatively few in number. I then look in more detail at some features of the hesychast 1 See Kallistos Ware, “St Nikodimos and the Philokalia,” in Brock Bingaman & Bradley Nassif (eds.), Th e Philokalia: A Classic Text of Orthodox Spirituality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 9–35, at 15.