Be Still and Listen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

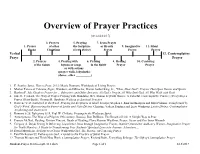

Overview of Prayer Practices

Overview of Prayer Practices (revised 4/2/17) 3. Prayers 5. Praying 7. Jesus Prayer 1. Prayer of other the Scripture or Breath 9. Imaginative 11. Silent Books Christians (lectio divina) Prayer Prayer Prayer Verbal 12. Contemplative Praye Prayer 2. Prayers 4. Praying with 6. Praying 8. Healing 10. Centering of the Saints hymns or songs in the Spirit Prayer Prayer or with actions (prayer walk, labyrinth,) (dance, other __________) 1. E. Stanley Jones, How to Pray, 2015; Maxie Dunnam, Workbook of Living Prayer; 2. Mother Teresa of Calcutta, Signs, Wonders, and Miracles; Martin Luther King, Jr., "Thou, Dear God": Prayers That Open Hearts and Spirits 3. Rueben P. Job, Guide to Prayer for ... (Ministers and Other Servants, All God’s People, All Who Seek God, All Who Walk with God) 4. Jane E. Vennard, The Way of Prayer; Praying with Mandalas; Rev. Sharon Seyfarth Garner, A Colorful, Contemplative Practice; Every Step a Prayer (Print Book); Thomas R. Hawkins, Walking as Spiritual Practice 5. Norvene Vest, Gathered in the Word: Praying the Scriptures in Small Groups; Stephen J. Binz and Kaspars and Ruta Poikans, Transformed by God’s Word: Discovering the Power of Lectio and Visio Divina; Christine Valters Paintner and Lucy Wynkoop, Lectio Divina: Contemplative Awakening and Awareness 6. Romans 8:26, Ephesians 6:18, Paul W. Chilcote, Praying in the Wesleyan Spirit 7. Annonymous, The Way of a Pilgrim(19th century, Russia); Ron DelBene, The Breath of Life: A Simple Way to Pray 8. Francis McNutt, Healing; Kristen Vincent, Beads of Healing; Flora Slosson Wuellner, Prayer, Stress and Our Inner Wounds 9. -

Consciousness of God As God Is: the Phenomenology of Christian Centering Prayer

CONSCIOUSNESS OF GOD AS GOD IS: THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF CHRISTIAN CENTERING PRAYER BY BENNO ALEXANDER BLASCHKE A dissertation submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington (2017) Abstract In this study I aim to give an alternative approach to the way we theorise in the philosophy and comparative study of mysticism. Specifically, I aim to shift debate on the phenomenal nature of contemplative states of consciousness away from textual sources and towards reliable and descriptively rich first-person data originating in contemporary practices of lived traditions. The heart of this dissertation lies in rich qualitative interview data obtained through recently developed second-person approaches in the science of consciousness. I conducted in-depth phenomenological interviews with 20 Centering Prayer teachers and practitioners. The interviews covered the larger trajectory of their contemplative paths and granular detail of the dynamics of recent seated prayer sessions. I aided my second-person method with a “radical participation” approach to fieldwork at St Benedict’s Monastery in Snowmass. In this study I present nuanced phenomenological analyses of the first-person data regarding the beginning to intermediate stages of the Christian contemplative path, as outlined by the Centering Prayer tradition and described by Centering Prayer contemplatives. My presentation of the phenomenology of Centering Prayer is guided by a synthetic map of Centering Prayer’s (Keating School) contemplative path and model of human consciousness, which is grounded in the first-person data obtained in this study and takes into account the tradition’s primary sources. -

Centering Prayer, As in All Methods Leading to Contemplative Prayer, Is the Indwelling Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit

Theological Background The source of Centering Prayer, as in all methods leading to contemplative prayer, is the indwelling Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The focus of Centering Prayer is the deepening of our relationship with the living Christ. It tends to build communities of faith and bond the members Be still and know that I am God. together in mutual friendship and love. PSALM 46:10 The Root of Centering Prayer Listening to the word of God in Scripture (Lectio Divina) is a traditional way of cultivating friendship Contemplative Prayer with Christ. It is a way of listening to the texts of We may think of prayer as thoughts or feelings Scripture as if we were in conversation with Christ expressed in words. But this is only one expression. and he were suggesting the topics of conversation. The Method of In the Christian tradition contemplative prayer The daily encounter with Christ and reflection on For information and resources: is considered to be the pure gift of God. It is the his word leads beyond mere acquaintanceship to an opening of mind and heart - our whole being - attitude of friendship, trust, and love. Conversation Contemplative Outreach, Ltd. CENTERING to God, the Ultimate Mystery, beyond thoughts, simplifies and gives way to communing. Gregory 10 Park Place, 2nd Floor, Suite B words, and emotions. Through grace we open our the Great (6th century) in summarizing the Butler, NJ 07405 awareness to God whom we know by faith is within Christian contemplative tradition expressed it as PRAYER 973.838.3384 us, closer than breathing, closer than thinking, closer “resting in God.” This was the classical meaning of [email protected] THE PRAYER OF CONSENT than choosing, closer than consciousness itself. -

Facilitator Handbook

Facilitator Handbook Serving Others on the Spiritual Journey in Community Publication Date – April 2019 © 2018. Contemplative Outreach Ltd. Butler, New Jersey. USA. All Rights Reserved. Facilitator Handbook – April 2019 Serving Others on the Spiritual Journey in Community Copyright 2019. All Rights Reserved. No portion of the material contained in this document may be copied or distributed without express written consent of Contemplative Outreach, Ltd. Contemplative Outreach, Ltd. 10 Park Place, 2nd Floor, Suite B, Butler, New Jersey 07405 973-838-3384 Fax 973-492-5795 www.contemplativeoutreach.org [email protected] © 2019. Contemplative Outreach, Ltd. All Rights Reserved. 2 Facilitator Handbook – April 2019 Serving Others on the Spiritual Journey in Community Acknowledgements Acknowledgement is gratefully made to Contemplative Outreach for permission to either reprint or edit excerpts from the online material. Edited 2013 for Contemplative Outreach by Bonnie J. Shimizu for use by all facilitators in the community of Contemplative Outreach. Edited 2018 by the Contemplative Outreach Facilitator Formation and Enrichment Service Team. Edited 2019 to update Service Team name from to Contemplative Outreach Facilitator Formation and Enrichment Service Team to Centering Prayer Group Facilitator Support Service Team. © 2019. Contemplative Outreach, Ltd. All Rights Reserved. 3 Facilitator Handbook – April 2019 Serving Others on the Spiritual Journey in Community Preface The purpose of this handbook is to provide structure, resources, and tools that a facilitator for a Centering Prayer group can use while supporting and empowering others on the spiritual journey. Typically, a Centering Prayer group is formed by persons who have an established prayer practice (or wish to establish one), often as a result of attending a Centering Prayer Introductory Program. -

The Centering Prayer Method by Thomas Keating, O.C.S.O

The Centering Prayer Method By Thomas Keating, O.C.S.O The following clarifications are in order concerning the Centering Prayer Method. 1. Centering Prayer is a traditional form of Christian prayer rooted in Scripture and based on the monastic heritage of “LectioDivina”. It is not to be confused with Transcendental Meditation or Hindu or Buddhist methods of meditation. It is not a New Age technique. Centering Prayer is rooted in the word of God, both in scripture and in the person of Jesus Christ. It is an effort to renew the Christian contemplative tradition handed down to us in an uninterrupted manner from St. Paul, who writes of the intimate knowledge of Christ that comes through love. Centering Prayer is designed to prepare sincere followers of Christ for contemplative prayer in the traditional sense in which spiritual writers understood that term for the first sixteen centuries of the Christian era. This tradition is summed up by St. Gregory the Great at the end of the sixth century. He describes contemplation as the knowledge of God impregnated with love. For Gregory, contemplation was the fruit of reflection on the word of God in Scripture as well as the precious gift of God. He calls it, "resting in God". In this “resting”, the mind and heart are not so much seeking God as beginning to experience, "to taste", what they have been seeking. This state is not the suspension of all activity, but the reduction of many acts and reflections into a single act or thought to sustain one's consent to God's presence and action. -

Dissertation (PDF)

DISSERTATION APPROVED BY /0.5. f B Date Jaci Jenkins Lindburg, Ph.D., Chair *0 Peggy Hawkins, Ph.D., Committee Member J Moss Breen, Ph.D., Director Gail M. Jensen, Ph.D., Dean AN INTERPRETATIVE PHENOMENOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF CENTERING PRAYER ____________________________________ By Charles D. Rhodes ____________________________________ A DISSERTATION IN PRACTICE Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate School of Creighton University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Interdisciplinary Leadership ____________________________________ Omaha, NE October 5, 2018 Copyright 2018, Charles D. Rhodes This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no part of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. iii Abstract Centering prayer is a contemplative practice designed to facilitate psychological and spiritual growth and development. It is currently being practiced in Christian communities and faith-based organizations around the world. Despite the widespread appeal and practice of centering prayer, the social scientific understanding of this psychospiritual practice is extremely limited. As such, leaders are limited in their ability to make evidence-based decisions regarding the use of centering prayer within their communities and organizations. To help clarify the programming decisions of leaders, this study examined the psychological and spiritual experiences of eight advanced adult centering prayer practitioners using the research methods of interpretative phenomenological analysis. Data were collected using a semi-structured interview format, hand coded, and analyzed for basic and recurrent themes. The results of the analysis yielded 35 general themes that were clustered into 5 superordinate themes: (a) Psychological Health and Wholeness; (b) Self-Development; (c) Healthy Relational Dynamics; (d) Mystical Experiences; and (e) Spiritual Growth and Development. -

St. Teresa of Avila and Centering Prayer

The Published Articles of Ernest E. Larkin, O.Carm. St. Teresa of Avila And Centering Prayer St. Teresa of Avila and Centering Prayer Introduction prayer form does not seem to have entered her purview. The purpose of this study is to locate Broadening centering prayer in this St Teresa of Avila in the contemporary terrain fashion is neither arbitrary or pointless. of centering prayer. Centering prayer is a new Teresa’s experience and doctrinal exposition term but an old reality, originating with include elements from both methods; far Thomas Merton’s insight into centering as the better then to put the two under a common movement from the false to the true self and umbrella. The very nature of contemplation developed as a prayer form by the Cistercians and the privileged ways of achieving it are at Basil Pennington, Thomas Keating and others, stake in this inquiry. Contemplation, as the and by the Benedictine John Main. This form obscure, infused, loving knowledge of God, is of prayer seeks to maintain a contemplative beyond images and concepts. But it does not contact with God beyond any particular follow that this gift of wisdom is always images and concepts through the use of the experienced as apophatic, that is, dark, holy word or mantra. The prayer is negative and contentless. Contemplation can contemplative in thrust but active in method, also be experienced as kataphatic, that is, as inasmuch as it is within human possibility and light, positive and concrete. In this case God choice and recommends itself to mature might be experienced in as well as beyond the Christians, who have thought and prayed image. -

NTSW Praying Ceaselessly Syllabus

New Theological Seminary of the West PRAYING CEASELESSLY—A SUMMER COURSE ON PRAYER Rejoice always, pray without ceasing, give thanks in all circumstances; for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you. 1 Thessalonians 5:16-18 Janna Gosselin, PhD Summer 2017 Location: La Canada Presbyterian Church July 26--September 13 Foothill Blvd, La Canada, CA and online via Moodle Time: 7-8:30 pm and online The class meets on Wednesday evenings from July 26 through August 23 and online. Additional materials and video viewings will be available online. A self-directed retreat will be scheduled at the student’s convenience. COURSE DESCRIPTION “I have abandoned all particular forms of devotion, all prayer techniques. My only prayer practice is attention. I carry on a habitual, silent, and secret conversation with God that fills me with overwhelming joy.” –Brother Lawrence Although Brother Lawrence claimed to have abandoned all prayer techniques to find a way to carry on this habitual, silent and secret conversation with God, most of us find it difficult to achieve this constant conversation with God without some form of devotional practice or technique. In this class, we will consider the forms of devotion—the “prayer techniques”—that have helped Christians over the years to develop that sense of the presence of God. Our analysis will hinge on two categories of prayer: cataphatic and apophatic prayer. We will examine the “cataphatic” approach by learning of methods of prayer expressed in Scripture, poetry and other types of “word” prayer. We will also consider the apophatic approach, which has included wordless prayer, silence and solitude to find and unite with God. -

Contemplative Prayer and Meditation : Their Role in Spiritual Growth

ABSTRACT CONTEMPLATIVE PRAYER AND MEDITATION AND THEIR ROLE IN SPIRITUAL GROWTH by Karen L. Bray This dissertation covers the role of contemplative prayer and meditation and the role they may play in spiritual growth. This project included a model for teaching various contemplative practices. The means of teaching these practices included lecture, small group experiential opportunities, and individual practices. The participants for this research were primarily, white, middle-class members of the United Methodist Church. Many, but not all of the participants had previous experience with contemplative prayer and meditation. The project was founded upon theological and historical Christian foundations of meeting God in moments of stillness and contemplation. Each weekly session focused on a contemplative practice, its historical and theological background and experiencing the practice as a small group. The participants were given the opportunity to experience the practice during the following week and to journal about their experience. Evaluation of the project was based on pre- and post-tests, journal entries and short answer questionnaires. The research revealed that participants felt a closer relationship with God after practicing contemplative prayer and meditation. They also came to understand that contemplative prayer was accessible to all Christians. CONTEMPLATIVE PRAYER AND MEDITATION: THEIR ROLE IN SPIRITUAL GROWTH A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Asbury Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements -

What Is Centering Prayer?

Centering Prayer Group at Siena Center, Racine WI Thursdays 7-8 a.m. Siena Retreat Center Need a midweek refresher time? Start your day praying with others- 20 minutes of silent centering prayer; followed by 20 minutes of input and some brief discussion on prayer or spirituality. We will not meet on Nov. 25 and Dec. 30 The group will be facilitated by Rev. Michael Mueller, pastor of St. Andrew’s Lutheran Church, Racine and Pat Shutts, from the retreat staff of the Siena Retreat Center. Siena Center is located at 5635 Erie St. Racine, WI 53402 Questions? Call Pat at (262)639-4100 X1238 or visit www.racinedominicans.org What is Centering Prayer? Centering Prayer is a method of prayer, which prepares us to be more aware of gift of God’s presence always with us. This awareness has been known as contemplative prayer. By quieting our faculties we open ourselves to the Spirit’s presence. It is a receptive prayer of resting in God. It’s main purpose is to deepen one’s relationship with God. Daily practice can open us to a greater consciousness of God’s presence in us and around us. Centering Prayer is drawn from ancient prayer practices of the Christian contemplative heritage, notably the Fathers and Mothers of the Desert, Lectio Divina (praying with scriptures), The Cloud of Unknowing, St. John of the Cross, and St. Teresa of Avila. In the 1970’s, three Trappist monks, Fr. William Meninger, Fr. Basil Pennington, and Abbot Thomas Keating of St. Joseph’s Abbey in Spencer, Massachusetts combined their monastic experience and the rich Christian contemplative heritage to come up with the method known today as Centering Prayer. -

The Heart of Centering Prayer: Nondual Christianity in Theory and Practice, Cynthia Bourgeault

Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology The Journal of the Graduate Theological Union Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology Volume 3, Issue 1 ISSN 2380-7458 Book Review The Heart of Centering Prayer: Nondual Christianity in Theory and Practice by Cynthia Bourgeault Author(s): Andrew K. Lee Source: Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology 3, no. 1 (2017): 153-158 Published By: Graduate Theological Union © 2017 Online article published on: August 1, 2017 Copyright Notice: This file and its contents is copyright of the Graduate Theological Union. All rights reserved. Your use of the Archives of the Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology (BJRT) indicates your acceptance of the BJRT’s policy regarding use of its resources, as discussed below. Any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form is prohibited with the following exceptions: Ø You may download and print to a local hard disk or on paper this entire article for your personal and non- commercial use only. Ø You may quote short sections of this article in other publications with the proper citations and attributions. Ø Permission has been obtained from the Journal’s management for eXceptions to redistribution or reproduction. A written and signed letter from the Journal must be secured eXpressing this permission. To obtain permissions for eXceptions, or to contact the Journal regarding any questions regarding further use of this article, please e-mail the managing editor at [email protected] The Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology aims to offer its scholarly contributions free to the community in furtherance of the Graduate Theological Union’s scholarly mission. -

What Is Centering Prayer?

Hold Fast to Sound Teaching What Is Centering Prayer? “The time is coming when people will not endure sound teaching, but having itching ears they will What Is There are really two different types of centering accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their prayer, one of which is beneficial and own likings, and will turn away from listening to recommended for Christians to practice and the truth and wander into myths” (2 Tim. 4:3). another that is not. The good kind of centering As Catholics, we have a wealth of spiritual expression available to us. In the Eucharist at prayer involves quieting the mind (but not Mass we become one in body and spirit with Centering emptying it) by focusing on a sacred word of Our Savior who loves us! In Confession we phrase, as a way of eliminating distractions in experience the fullness of His mercy. In the Rosary we see the events of Jesus’ life prayer and entering into a deeper, more through the eyes of His Mother. In Lectio gratifying relationship with God. This kind of Divina we experience the word of God in a prayer is akin to the contemplative prayer of deeply personal way. Through charismatic Prayer? prayer we live the abundant life of the Spirit. the great Catholic mystics—Saints Teresa of Through the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius Avila, John of the Cross, and Ignatius Loyola. Loyola we achieve true self-possession. We do The bad kind of centering prayer involves the not need to experiment with hazardous forms of spirituality that will lead us astray from the And is it good attempt to completely turn off the mind, truths the Lord has revealed to us through His emptying it of all thoughts, and also tends to be Church on earth.