1 Jerusalem and the Work of Discontinuity Elizabeth Key Fowden He Was Not Changing a Technique, but an Ontology. John Berger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nil Sorsky: the Authentic Writings Early 18Th Century Miniature of Nil Sorsky and His Skete (State Historical Museum Moscow, Uvarov Collection, No

CISTER C IAN STUDIES SERIES : N UMBER T WO HUNDRED T WENTY -ONE David M. Goldfrank Nil Sorsky: The Authentic Writings Early 18th century miniature of Nil Sorsky and his skete (State Historical Museum Moscow, Uvarov Collection, No. 107. B 1?). CISTER C IAN STUDIES SERIES : N UMBER T WO H UNDRED TWENTY -ONE Nil Sorsky: The Authentic Writings translated, edited, and introduced by David M. Goldfrank Cistercian Publications Kalamazoo, Michigan © Translation and Introduction, David M. Goldfrank, 2008 The work of Cistercian Publications is made possible in part by support from Western Michigan University to The Institute of Cistercian Studies Nil Sorsky, 1433/1434-1508 Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Nil, Sorskii, Saint, ca. 1433–1508. [Works. English. 2008] Nil Sorsky : the authentic writings / translated, edited, and introduced by David M. Goldfrank. p. cm.—(Cistercian studies series ; no. 221) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN 978-0-87907-321-3 (pbk.) 1. Spiritual life—Russkaia pravoslavnaia tserkov‚. 2. Monasticism and religious orders, Orthodox Eastern—Russia—Rules. 3. Nil, Sorskii, Saint, ca. 1433–1508—Correspondence. I. Goldfrank, David M. II. Title. III. Title: Authentic writings. BX597.N52A2 2008 248.4'819—dc22 2008008410 Printed in the United States of America ∆ Estivn ejn hJmi'n nohto;~ povlemo~ tou' aijsqhtou' calepwvtero~. ¿st; mysla rat;, vnas= samäx, h[v;stv÷nyã l[täi¡wi. — Philotheus the Sinaite — Within our very selves is a war of the mind fiercer than of the senses. Fk 2: 274; Eparkh. 344: 343v Table of Contents Author’s Preface xi Table of Bibliographic Abbreviations xvii Transliteration from Cyrillic Letters xx Technical Abbreviations in the Footnotes xxi Part I: Toward a Study of Nil Sorsky I. -

Course Listing Hellenic College, Inc

jostrosky Course Listing Hellenic College, Inc. Academic Year 2020-2021 Spring Credit Course Course Title/Description Professor Days Dates Time Building-Room Hours Capacity Enrollment ANGK 3100 Athletics&Society in Ancient Greece Dr. Stamatia G. Dova 01/19/2105/14/21 TBA - 3.00 15 0 This course offers a comprehensive overview of athletic competitions in Ancient Greece, from the archaic to the hellenistic period. Through close readings of ancient sources and contemporary theoretical literature on sports and society, the course will explore the significance of athletics for ancient Greek civilization. Special emphasis will be placed on the Olympics as a Panhellenic cultural institution and on their reception in modern times. ARBC 6201 Intermediate Arabic I Rev. Edward W. Hughes R 01/19/2105/14/21 10:40 AM 12:00 PM TBA - 1.50 8 0 A focus on the vocabulary as found in Vespers and Orthros, and the Divine Liturgy. Prereq: Beginning Arabic I and II. ARTS 1115 The Museums of Boston TO BE ANNOUNCED 01/19/2105/14/21 TBA - 3.00 15 0 This course presents a survey of Western art and architecture from ancient civilizations through the Dutch Renaissance, including some of the major architectural and artistic works of Byzantium. The course will meet 3 hours per week in the classroom and will also include an additional four instructor-led visits to relevant area museums. ARTS 2163 Iconography I Mr. Albert Qose W 01/19/2105/14/21 06:30 PM 09:00 PM TBA - 3.00 10 0 This course will begin with the preparation of the board and continue with the basic technique of egg tempera painting and the varnishing of an icon. -

Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa

Durham E-Theses Language and theology in St Gregory of Nyssa Neamµu, Mihail G. How to cite: Neamµu, Mihail G. (2002) Language and theology in St Gregory of Nyssa, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4187/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk University of Durham Faculty of Arts Department of Theology The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa Mihail G. Neamtu St John's College September 2002 M.A. in Theological Research Supervisor: Prof Andrew Louth This dissertation is the product of my own work, and the work of others has been properly acknowledged throughout. Mihail Neamtu Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa MA (Research) Thesis, September 2002 Abstract This MA thesis focuses on the work of one of the most influential and authoritative theologians of the early Church: St Gregory of Nyssa (f396). -

Emerging Trends in Real Estate Europe 2016

Emerging Trends in Real Estate® Beyond the capital Europe 2016 Contents 26 Chapter 3 Markets to watch 4 Chapter 1 Business environment 2 16 Executive Chapter 2 summary Real estate capital markets Cover image: Marie-Elisabeth Lüders Building, Berlin, Germany 2 Emerging Trends in Real Estate® Europe 2016 Contents 71 About the survey Emerging Trends in Real Estate® Europe 2016 Beyond the capital A publication from PwC and the Urban Land Institute 60 Chapter 4 Changing places Emerging Trends in Real Estate® Europe 2016 1 Executive summary Executive summary 2 Emerging Trends in Real Estate® Europe 2016 Executive summary Capital flows and city rankings will always attract the headlines, The vast majority of respondents are but this year Emerging Trends Europe shines a spotlight on confident in their ability to thrive in 2016. fundamental changes at the business end of the real estate However, they acknowledge it is an increasingly competitive global field for industry. It reveals an industry trying to come to terms with the real estate. They are aware that if the wall needs of occupiers and the disruptive forces of technology, of capital recedes, European markets demographics, social change and rapid urbanisation. could be left exposed. Then it will be the strength of the underlying market These ground-level disruptions are Low interest rates and the sheer weight fundamentals and management’s permeating through the entire real estate of capital bearing down on European operational skills that come into focus. value chain. Investors are focused on real estate mean that most remain bullish cities and assets rather than countries. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnadon Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 A CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPOEU^.RY IRAQI ART USING SIX CASE STUDIES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mohammed Al-Sadoun ***** The Ohio Sate University 1999 Dissertation Committee Approved by Dr. -

Spiritual Struggle and Gregory of Nyssa's Theory of Perpetual Ascent

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-10-2019 Spiritual Struggle and Gregory of Nyssa’s Theory of Perpetual Ascent: An Orthodox Christian Virtue Ethic Stephen M. Meawad Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Ethics in Religion Commons Recommended Citation Meawad, S. M. (2019). Spiritual Struggle and Gregory of Nyssa’s Theory of Perpetual Ascent: An Orthodox Christian Virtue Ethic (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1768 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. SPIRITUAL STRUGGLE AND GREGORY OF NYSSA’S THEORY OF PERPETUAL ASCENT: AN ORTHODOX CHRISTIAN VIRTUE ETHIC A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Stephen M. Meawad May 2019 Copyright by Stephen Meawad 2019 SPIRITUAL STRUGGLE AND GREGORY OF NYSSA’S THEORY OF PERPETUAL ASCENT: AN ORTHODOX CHRISTIAN VIRTUE ETHIC By Stephen M. Meawad Approved December 14, 2018 _______________________________ _______________________________ Darlene F. Weaver, Ph.D. Elizabeth A. Cochran, Ph.D. Professor of Theology Associate Professor of Theology Director, Ctr for Catholic Intellectual Tradition Director of Graduate Studies (Committee Chair) (Committee Member – First Reader) _______________________________ _______________________________ Bogdan G. Bucur, Ph.D. Marinus C. Iwuchukwu, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Theology Associate Professor of Theology (Committee Member – Second Reader) Chair, Department of Theology Chair, Consortium Christian-Muslim Dial. -

Church Lectionary & Typicon Church Services and Events St John's

Saint John The Baptist Orthodox Church September 23, 2018 Church Lectionary & Typicon Seventeenth Sunday After Pentecost Sunday Before the Elevation of the Cross Virgin Martyrs Menodora, Metrodora, & Nymphodora Epistle : Galatians 6:11-18; Gospel : Mark3:13-27 St John The Baptist Orthodox Church Resurrectional Tone 8 1240 Broadbridge Ave Stratford, CT 06615 FIFTEENTH SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST www.sjoc.org Church Services and Events www.facebook.com/stjohns broadbridge The Venerable Poemen the Great Sunday, September 23 12:00PM Church Picnic Very Rev. Protopresbyter Peter Paproski Wednesday, September 26 Epistle : 2 Corinthians 4:6-15; [email protected] Gospel : Matthew 22: 35-48 6:30PM Great Vespers & Litya 7:30PM Adult Education Thursday, September 27 Office: 203-375-2564 Resurrectional Tone 6 Cell: 203-260-0423 9:00AM Divine Liturgy - Elevation of The Cross – Strict Fast Day _______________________ Saturday, September 29 Resurrectional Tone 5 9:00AM Pagachi Workshop A Parish of The American 5:00PM Great Vespers Carpatho-Russian Sunday, September 30 Resurrectional Tone 3 Orthodox Diocese 9:00AM Divine Liturgy 10:45AM Church School St John’s Stewards Diocesan Website: Date Coffee Hour Host Hours Epistle Church Cleaner http://www.acrod.org Sept 30 Decerbo Holly Bill Cleaning Service Camp Nazareth: http://www.campnazareth.org Oct 7 Ivers/Pierce Pani Carol Matt Cleaning Service Facebook: www.facebook.com/acroddiocese Twitter: 2018 Parish Stewardship Offering (As of 09/16 /18) https://twitter.com/acrodnews YTD: $48,209 .00 Goal: $70,000.00 You Tube: https://youtube.com/acroddiocese Announcements Lives of The CHURCH SCHOOL - The 2018-2019 Church School Year began last Sunday. -

Ignatian and Hesychast Spirituality: Praying Together

St Vladimir’s Th eological Quarterly 59:1 (2015) 43–53 Ignatian and Hesychast Spirituality: Praying Together Tim Noble Some time aft er his work with St Makarios of Corinth (1731–1805) on the compilation of the Philokalia,1 St Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain (1748–1809) worked on a translation of an expanded version of the Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius Loyola.2 Metropolitan Kallistos Ware has plausibly suggested that the translation may have been motivated by Nikodimos’ intuition that there was something else needed to complement the hesychast tradition, even if only for those whose spiritual mastery was insuffi cient to deal with its demands.3 My interest in this article is to look at the encounters between the hesychast and Ignatian traditions. Clearly, when Nikodimos read Pinamonti’s version of Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises, he found in it something that was reconcilable with his own hesychast practice. What are these elements of agreement and how can two apparently quite distinct traditions be placed side by side? I begin my response with a brief introduction to the two traditions. I will also suggest that spiritual traditions off er the chance for experience to meet experience. Moreover, this experience is in principle available to all, though in practice the benefi ciaries will always be relatively few in number. I then look in more detail at some features of the hesychast 1 See Kallistos Ware, “St Nikodimos and the Philokalia,” in Brock Bingaman & Bradley Nassif (eds.), Th e Philokalia: A Classic Text of Orthodox Spirituality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 9–35, at 15. -

Research Report Events & Activities July 2015 — December 2018 Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz — Max-Planck-Institut Institut in Florenz Kunsthistorisches

Research Report Events & Activities July 2015 — December 2018 Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz — Max-Planck-Institut Institut in Florenz Kunsthistorisches Research Report Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz Max-Planck-Institut Events & Activities July 2015 — December 2018 Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz Max-Planck-Institut Via Giuseppe Giusti 44 50121 Florence, Italy Phone +39 055 249 11-1 Fax + 39 055 249 11-55 www.khi.fi.it © 2019 Editors: Alessandro Nova and Gerhard Wolf Copy editing and proof-reading: Hannah Baader, Carolin Behrmann, Helene Bongers, Robert Brennan, Jason Di Resta, Dario Donetti, Hana Gründler, Stephanie Hanke, Annette Hoffmann, Lucy Jarman, Fabian Jonietz, Albert Kirchengast, Marco Musillo, Oliver O’Donnell, Jessica N. Richardson, Brigitte Sölch, Eva-Maria Troelenberg, Tim Urban, and Samuel Vitali Design and typesetting: Micaela Mau Print and binding: Stabilimento Grafico Rindi Cover image: Antonio Di Cecco, Monte Vettore, June 2018 Contents 7 Scientific Advisory Board 9 Events & Activities of the Institute 11 Conferences 31 Evening Lectures 34 Seminars & Workshops 38 Matinées & Soirées 39 Study Trips 41 Awards, Roundtables & Presentations 42 Labor 45 Ortstermin 46 Study Groups 47 Studienkurse 50 Online Exhibitions 51 Exhibition Collaborations 53 Academic Activities of the Researchers 54 Teaching 57 Talks 81 External Conference Organization 84 Curated Exhibitions 86 Varia 93 Publications 94 Publications of the Institute 97 Publications of the Researchers 117 Staff Directories Scientific Advisory Board Prof. Dr. Maria Luisa Catoni IMT School for Advanced Studies Lucca Prof. Dr. Elizabeth Edwards De Montfort University Prof. Dr. Jaś Elsner Corpus Christi College Prof. Dr. Charlotte Klonk Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Institut für Kunst- und Bildgeschichte Prof. Dr. -

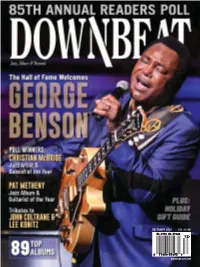

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

35 Years of Occupation a New Acquisition by the British Museum

Features 207 35 Prints – 35 Years of Occupation A new acquisition by the British Museum By Venetia Porter As part of its continuing policy of acquiring modern and contemporary art from the Middle East, this short article highlights an exciting recent acquisition of a set of prints by Palestinian and Israeli artists. It was made thanks to the generosity of a newly formed group of supporters who are helping the British Museum source and fund appropriate acquisitions. The works that interest us for the growing collection include those that tell powerful stories about contemporary life or historical events in the Middle East. The Israel-Palestine conflict is the single most important narrative that continues to dominate the politics and the daily lives of the peoples of this region and this set of screen prints was the product of a desire by Palestinian and Israeli artists to promote their ideals of a shared peaceful future. The idea came about in June 2002, and this is the artists’ accompanying statement: “In defiance of the painful situation in which we presently find ourselves - violent, oppressive and seemingly without a solution - and in a direct challenge to the renewed threat of population transfer, re-occupation and terror, we, as artists are determined to persist in our efforts to promote peaceful dialogue, towards a shared peaceful future for both peoples.” Rula Halawani 208 Features Khaled Hourani Asad Azi David Reeb Nabil Anani The entire portfolio of 35 prints - referring to 35 years of occupation (between 1967 and 2002) - was printed at the Har-El Print Workshop in Jaffa.