Environmental Impact Report FINAL SCH #2016092008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 1999 SCREE

October, 2007 Peak Climbing Section, Loma Prieta Chapter, Sierra Club Vol. 41 No. 10 World Wide Web Address: http://lomaprieta.sierraclub.org/pcs/ General Meeting Editor’s Notes Date: October 9, 2007 Winter made a brief appearance last week with snow falling in the mountains (see the Highland Peak report). Expect a gorgeous time of the year for outside activity Time: 7:30 pm in the wilderness using skis, snowshoes or just feet. Where: Peninsula Conservation Center This year we introduce a new kind of trip for those who 3921 E. Bayshore Rd. are more ambitious than the would-be tripper that curls Palo Alto, CA up by the fire with a good book. Called the BSS, Backcountry Ski Series, the offering is a day trip into the backcountry once a month, typically in the Tahoe Program: Canyoneering - area. The trips are scheduled for Friday because North Fork of the Kaweah River Thursday night traffic after 7 pm is quick and smooth while Friday is terrible. Also a Friday outing allows the leaders to recover enough to race in the citizen class Presenter: Toinette Hartshorne races each Sunday or Monday. People may attend one or all trips. Tips on Telemark and Randonee skiing will be available, but participants need to have advanced This past summer, Jef Levin and Toinette skiing skills. Typically there will be anywhere from completed the first descent of the North Fork of good to great powder. the Kaweah River. Several weekends were spent scouting and rigging the technical sections in the Avalanche beacons as well as shovels and probes are beautiful granite canyons carved by this river. -

Upper Mokelumne Management Unit

AQUATIC BIODIVERSITY MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE UPPER MOKELUMNE MANAGEMENT UNIT 2016 Prepared By Sarah Mussulman Environmental Scientist Mitch Lockhart Environmental Scientist And Kevin Thomas Kimberly Gagnon NORTH CENTRAL REGION DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE STATE OF CALIFORNIA TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................... II LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................. III SECTION I .............................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 1 1) OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................. 2 2) FACTORS AFFECTING THE SIERRA NEVADA YELLOW-LEGGED FROG ........................... 3 3) REGULATORY STATUS OF THE SIERRA NEVADA YELLOW-LEGGED FROG ................... 4 4) RESOURCE ASSESSMENT METHODS ................................................................................... 5 5) FISHERIES MANAGEMENT TECHNIQUES ............................................................................. 6 6) AMPHIBIAN MANAGEMENT TECHNIQUES ............................................................................. 7 7) MONITORING ............................................................................................................................ -

2020 El Dorado Irrigation District Temporary Water Transfer

PUBLIC DRAFT INITIAL STUDY/PROPOSED NEGATIVE DECLARATION 2020 El Dorado Irrigation District Temporary Water Transfer MARCH 2020 PREPARED FOR: El Dorado Irrigation District 2890 Mosquito Road Placerville, CA, 956670 NOTICE OF INTENT TO ADOPT A NEGATIVE DECLARATION NOTICE OF PUBLIC HEARING 2020 EL DORADO IRRIGATION DISTRICT TEMPORARY WATER TRANSFER The El Dorado Irrigation District (EID) proposes to adopt a Negative Declaration pursuant to the California Environmental Quality Act (Section 15000 et seq., Title 14, California Code of Regulations) for the 2020 EID Temporary Water Transfer Project (proposed project). EID plans to transfer up to 8,000 acre-feet (AF) of water to state and/or federal water contractors (Buyers) to be used by the Buyers in their service areas south of the Delta in 2020. EID proposes to transfer water to the Buyers during summer and fall 2020. EID would make the water available through re-operations of three EID reservoirs to release water otherwise planned to be consumed by EID customers and/or stored within the EID network of reservoirs. The involved reservoirs and rivers/creeks would all operate consistent with their historic flow and release schedules, and would meet all applicable rules and requirements, including but not limited to lake level and minimum streamflow requirements. The proposed 8,000-AF transfer quantity would consist of releases from Weber Reservoir (up to 850 AF) that would otherwise remain in Weber Reservoir and releases from Caples/Silver lakes (up to 8,000 AF) that would otherwise be added to storage in Jenkinson Lake or used directly to meet summer/fall 2020 demands that would instead be met with water previously stored in Jenkinson Lake. -

USGS Topographic Maps of California

USGS Topographic Maps of California: 7.5' (1:24,000) Planimetric Planimetric Map Name Reference Regular Replace Ref Replace Reg County Orthophotoquad DRG Digital Stock No Paper Overlay Aberdeen 1985, 1994 1985 (3), 1994 (3) Fresno, Inyo 1994 TCA3252 Academy 1947, 1964 (pp), 1964, 1947, 1964 (3) 1964 1964 c.1, 2, 3 Fresno 1964 TCA0002 1978 Ackerson Mountain 1990, 1992 1992 (2) Mariposa, Tuolumne 1992 TCA3473 Acolita 1953, 1992, 1998 1953 (3), 1992 (2) Imperial 1992 TCA0004 Acorn Hollow 1985 Tehama 1985 TCA3327 Acton 1959, 1974 (pp), 1974 1959 (3), 1974 (2), 1994 1974 1994 c.2 Los Angeles 1994 TCA0006 (2), 1994, 1995 (2) Adelaida 1948 (pp), 1948, 1978 1948 (3), 1978 1948, 1978 1948 (pp) c.1 San Luis Obispo 1978 TCA0009 (pp), 1978 Adelanto 1956, 1968 (pp), 1968, 1956 (3), 1968 (3), 1980 1968, 1980 San Bernardino 1993 TCA0010 1980 (pp), 1980 (2), (2) 1993 Adin 1990 Lassen, Modoc 1990 TCA3474 Adin Pass 1990, 1993 1993 (2) Modoc 1993 TCA3475 Adobe Mountain 1955, 1968 (pp), 1968 1955 (3), 1968 (2), 1992 1968 Los Angeles, San 1968 TCA0012 Bernardino Aetna Springs 1958 (pp), 1958, 1981 1958 (3), 1981 (2) 1958, 1981 1981 (pp) c.1 Lake, Napa 1992 TCA0013 (pp), 1981, 1992, 1998 Agua Caliente Springs 1959 (pp), 1959, 1997 1959 (2) 1959 San Diego 1959 TCA0014 Agua Dulce 1960 (pp), 1960, 1974, 1960 (3), 1974 (3), 1994 1960 Los Angeles 1994 TCA0015 1988, 1994, 1995 (3) Aguanga 1954, 1971 (pp), 1971, 1954 (2), 1971 (3), 1982 1971 1954 c.2 Riverside, San Diego 1988 TCA0016 1982, 1988, 1997 (3), 1988 Ah Pah Ridge 1983, 1997 1983 Del Norte, Humboldt 1983 -

Mokelumne Wilderness Management Guidelines

M~okelurilne.~wila·erness,:,, ·.. For~stSeryice' -- '~ ~ _, ~ t -, __ ~ _f Manag~ment.riqid·9lin:~~"- - ~ - - ' ~Pacific somllwestR~gici~ . ' . - -' . ' . ' .. •. artd!~t~r~~ntain ~egioii. ' '· '\' ·;Land· and Resource· > Man~g-~riler1~f. pl,an .· ·· Amel'ldmerit. ,. ~. · · · : "~ ~ -l /~- ... \ '· Mokelumne Wilderness Management Guidelines Land and Resource Management Plan Amendment March,2000 Pacific Southwest Region and Intermountain Regions Eldorado, Stanislaus and Toiyabe National Forests Responsible Agency: Forest Service United States Department of Agriculture Responsible Officials: Judie L. Tartaglia, Acting Forest Supervisor Eldorado National Forest 100 Forni Road Placerville, CA 95667 Ben del Villar, Forest Supervisor Stanislaus National Forest 19777 Greenley Road Sonora, CA 95370 Robert Vaught, Forest Supervisor Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest 1200 Franklin Way Sparks, NV 89431 Information Contact: Diana Erickson Eldorado National Forest 100 Forni Road Placerville, CA 95667 (530) 622-5061 TABLE OF CONTENTS Forest Plan Consistency 1 Management Emphasis 1 Area Description and Current Management Situation 1 Desired Future Conditions - Opportunity Class Descriptions 3 Summary Table of Opportunity ~lass Objectives 8 Table of Opportunity Class Allocations 12 Management Area Direction, Standards and Guidelines 13 Resource Area and Management Practices 14 Administrative Activities 14 Air Resources 16 Facilities (trails and signs) 17 Fire Management 21 Fish and Wildlife 22 Heritage Resources 24 Lands 27 Minerals 28 Range 28 Recreation -

National Wetlands Inventory Map Report for Sacramento NE

National Wetlands Inventory Map Report for Sacramento NE Project ID: Sacramento NE Project Title or Area: Sacramento NE 1:100,000 Project area covers the following 31 USGS 7.5 minute quadrangles contained within the Sacramento 1;100,000 quadrangle: Aukum Bear River Reservoir Caldor Camino Caples Lake Coloma Devil Peak Echo Lake Emerald Bay Fiddletown Garden Valley Georgetown Greenwood Kyburz Latrobe Leek Spring Hill Loon Lake Mokelumne Peak Omo Ranch Peddler Hill Placerville Pyramid Peak Riverton Robbs Peak Rockbound Valley Shingle Springs Slate Mountain Sly Park Stump Spring Tragedy Spring Tunnel Hill Source Imagery: Type: CIR for all quadrangles Scale: 1:58,000 for all quadrangles Date: See table below: USGS Quadrangle Photo Date(s) Aukum 6/84 Bear River Reservoir 8/84 Caldor 6/84 Camino 6/84 Caples Lake 8/84, 9/84 Coloma 6/84 Devil Peak 6/84 Echo Lake 8/84 Emerald Bay 8/84 Fiddletown 6/84 Garden Valley 6/84 Georgetown 6/84 Greenwood 6/84 Kyburz 8/84 Latrobe 6/84 Leek Spring Hill 8/84 Loon Lake 9/84 Mokelumne Peak 9/84 Omo Ranch 6/84 Peddler Hill 9/84 Placerville 6/84 Pyramid Peak 9/84 Riverton 9/84 Robbs Peak 9/84 Rockbound Valley 9/84 Shingle Springs 6/84 Slate Mountain 6/84 Sly Park 6/84 Stump Spring 9/84 Tragedy Spring 8/84 Tunnel Hill 6/84 Collateral Data: • USGS 1:24,000 topographic quadrangles • USDA Soil Surveys of Amador Area, El Dorado Area, El Dorado National Forest, Tahoe Basin Area, and Placer County, Western Part. -

Land Stewardship Proposal from the California Department of Forestry

Land Stewardship Proposal for the North Fork Mokelumne River Planning Unit California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection Tuesday, August 10, 2010 Contents PART 1 – ORGANIZATIONAL INFORMATION........................................................... 1 1. Contact Information................................................................................................... 1 2. Executive Summary................................................................................................... 1 3. Organizational Category ............................................................................................. 3 4. Organization's Tax Exempt Status.............................................................................. 3 5. Organization's Legal Name......................................................................................... 3 6. Organization's Common Name................................................................................... 3 7. Letter From the Executive Director ............................................................................ 3 8. Rationale for Applying ............................................................................................... 6 9. Organization's Mission ............................................................................................... 6 10. Geographic Focus ..................................................................................................... 7 11. Organizational Experience and Capacity................................................................. -

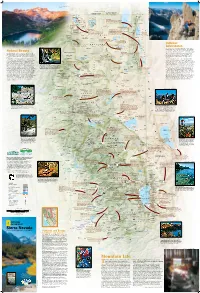

Sierra Nevada’S Endless Landforms Are Playgrounds for to Admire the Clear Fragile Shards

SIERRA BUTTES AND LOWER SARDINE LAKE RICH REID Longitude West 121° of Greenwich FREMONT-WINEMA OREGON NATIONAL FOREST S JOSH MILLER PHOTOGRAPHY E E Renner Lake 42° Hatfield 42° Kalina 139 Mt. Bidwell N K WWII VALOR Los 8290 ft IN THE PACIFIC ETulelake K t 2527 m Carr Butte 5482 ft . N.M. N. r B E E 1671 m F i Dalton C d Tuber k Goose Obsidian Mines w . w Cow Head o I CLIMBING THE NORTHEAST RIDGE OF BEAR CREEK SPIRE E Will Visit any of four obsidian mines—Pink Lady, Lassen e Tule Homestead E l Lake Stronghold l Creek Rainbow, Obsidian Needles, and Middle Fork Lake Lake TULE LAKE C ENewell Clear Lake Davis Creek—and take in the startling colors and r shapes of this dense, glass-like lava rock. With the . NATIONAL WILDLIFE ECopic Reservoir L proper permit you can even excavate some yourself. a A EM CLEAR LAKE s EFort Bidwell REFUGE E IG s Liskey R NATIONAL WILDLIFE e A n N Y T REFUGE C A E T r W MODOC R K . Y A B Kandra I Blue Mt. 5750 ft L B T Y S 1753 m Emigrant Trails Scenic Byway R NATIONAL o S T C l LAVA E Lava ows, canyons, farmland, and N E e Y Cornell U N s A vestiges of routes trod by early O FOREST BEDS I W C C C Y S B settlers and gold miners. 5582 ft r B K WILDERNESS Y . C C W 1701 m Surprise Valley Hot Springs I Double Head Mt. -

SPS List 20Th Ed Fin#3CA018.Cwk

price $1 Sierra Peaks Section—Angeles Chapter—Sierra Club SPS PEAKS LIST 20th Edition April 2009 248 Peaks CHANGE Change from the 19th Edition (August 2001): • Addition of Caltech Peak. PEAK INDEX Abbot - 17.9 Crag - 1.9 Goodale - 10.9 Lola - 24.5 Piute - 22.12 Striped - 10.8 Adams - 24.9 Dade - 17.8 Goode - 14.8 Lone Pine - 4.9 Powell - 15.2 Table - 7.6 Agassiz - 14.7 Dana - 21.8 Gould - 9.4 Lyell - 21.5 Prater - 12.3 Tallac - 23.11 Alta - 6.1 Darwin - 15.7 Granite Chief -24.1 Maclure - 21.4 Pyramid (N) - 23.9 Taylor Dome - 1.7 Angora - 2.2 Davis - 19.5 Gray - 20.3 Mallory - 4.3 Pyramid (S) - 10.6 Tehipite Dm. - 11.7 Arrow - 10.7 Deerhorn - 8.5 Guyot - 3.6 Marion - 11.2 Recess - 17.5 Temple Crag -14.1 Bago - 9.6 Devils Crags - 13.3 Haeckel - 15.4 Matterhorn - 22.9 Red and White -18.3 Thompson - 15.1 Baldwin - 18.7 Diamond - 9.12 Hale - 5.2 McAdie - 4.5 Red Kaweah - 6.9 Thor - 4.8 Banner - 19.4 Discks - 23.10 Half Dome - 20.6 McDuffie - 13.5 Red Peak - 20.2 Three Sisters-11.9 Barnard - 5.6 Disaappointment - 12.7 Harrington - 11.6 McGee - 15.11 Red Slate - 18.4 Thumb - 12.6 Basin - 16.4 Disaster - 23.4 Henry - 15.13 Mendel - 15.8 Reinstein - 13.10 Thunder - 7.7 Baxter - 10.1 Dragon - 9.10 Hermit - 15.10 Merced - 20.1 Ritter - 19.3 Thunderbolt - 14.5 Bear Crk.Sp.- 17.7 Dunderberg - 22.5 Highland - 23.5 Merriam - 17.1 Rixford - 9. -

Carson Pass–Kirkwood Paleocanyon System: Paleogeography of the Ancestral Cascades Arc and Implications for Landscape Evolution of the Sierra Nevada (California)

Carson Pass–Kirkwood paleocanyon system: Paleogeography of the ancestral Cascades arc and implications for landscape evolution of the Sierra Nevada (California) C.J. Busby† S.B. DeOreo Department of Earth Science, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 93101, USA I. Skilling Department of Geology and Planetary Sciences, University of Pittsburgh, 200 SRCC, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, USA P.B. Gans Department of Earth Science, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 93101, USA J.C. Hagan Department of Earth Science, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 93101, USA ABSTRACT Carson Pass–Kirkwood area of the central Range faulting in the central Sierra. The Sierra Nevada has allowed us to identify 6 late Miocene reincision may correspond to Tertiary strata of the central Sierra Nevada unconformity-bounded sequences preserved uplift attendant with the northward sweep are dominated by widespread, voluminous within a paleocanyon as deep as 650 m cut of the triple junction through the latitude of volcanic breccias that are largely undivided into Mesozoic granitic basement. The Car- the central Sierra. Paleocanyons of the cen- and undated, the origin of which is poorly son Pass–Kirkwood paleocanyon trends NE- tral Sierra differ from those of the northern understood. These dominantly andesitic SW, with a paleo-transport direction roughly and southern Sierra by showing steeper local strata are interpreted to be eruptive products parallel to the modern Mokelumne River paleorelief, and the bouldery stream depos- of the ancestral Cascades arc, deposited and drainage (toward the SW). Sequence 1 con- its attest to higher axial gradients than envi- preserved within paleocanyons that crossed sists of Oligocene silicic ignimbrites sourced sioned for other parts of the range. -

Hope Valley Field Trip Guide

ESP/ERS 30 -- The Global Ecosystem FIELD TRIP Guide: Davis to Hope Valley Sacramento Valley - Foothills - Sierra Nevada Slope and Crest Introduction This trip follows an eastward transect from Davis across the Sierra crest at Carson Pass. A. Communities. The smaller units of ecological pattern within biomes are usually called communities, though if you use Walter you will see much more ornate terms used by our German colleagues. But we don’t want complex terminology to get in our way. Too much books, too little nature! Since plants dominate the structure of communities, plants usually define communities. A word of warning about plant communities. Plants species are actually wildly individualistic in following the physical, chemical, and competitive factors that affect that particular species. Communities, like biomes, are very rough abstractions we use to give us some concepts to help our feeble minds to impose order on chaos. Think of real plant communities as integrated multiethnic neighborhoods, not as tightly segregated ones with only some species admitted not others. Alternatively, think of the idealized plant communities as how plant geography look if it were done to make life easy for book writers. Patterns exist, but they are anything but neat. On any given day, they vex, trouble, and thrill the biogeographers. Never a dull field trip anyway. 1. Central Valley Grassland - now primarily agricultural fields, 2. Oak Savannah and Foothill Woodland, 3. Chaparral, 4. Yellow Pine Forest, 5. Red Fir and Lodgepole Pine Forests, 6. Subalpine Forest, and 7. Mountain Meadow. B. Field Guides as an aid to observation Our slogan “read nature like a book, not books about nature” slights somewhat the value of good field guides. -

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 8 These Coordinates Were Derived

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 8 These coordinates were derived from Geographic Information System (GIS) digital files. The GIS files and their associated coordinates are not the legal source for determining critical habitat boundaries. Inherent in any data set used to develop graphical representations, are limitations of accuracy as determined by, among others, the source, scale and resolution of the data. While the Service makes every effort to represent the critical habitat shown with this data as completely and accurately as possible (given existing time and resource constraints), the USFWS gives no warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, or completeness of these data. In addition, the USFWS shall not be held liable for improper or incorrect use of the data described and/or contained herein. Graphical representations provided by the use of this data do not represent a legal description of the critical habitat boundary. The user is referred to the critical habitat map(s) and any accompanying regulatory text in the final rule for this species as published in the Federal Register. UTM mapping coordinates for proposed critical habitat for the Sierra Nevada Yellow-legged Frog (Rana sierrae) SUBUNIT: 1A Butte County and Plumas County,California. From USGS 1:24,000 topographic quadrangles Belden,Kimshew Point,Jonesville,and Storrie. Land bounded by the following UTM Zone 10,NAD 83 coordinates (E,N): 638396, 4425773; 638200, 4425840; 638060, 4425887; 638025, 4425868; 637981, 4425880; 637947, 4425927; 637753,