Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Glass Review 10.Pdf

'New Glass Review 10J iGl eview 10 . The Corning Museum of Glass NewG lass Review 10 The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 1989 Objects reproduced in this annual review Objekte, die in dieser jahrlich erscheinenden were chosen with the understanding Zeitschrift veroffentlicht werden, wurden unter that they were designed and made within der Voraussetzung ausgewahlt, dal3 sie the 1988 calendar year. innerhalb des Kalenderjahres 1988 entworfen und gefertigt wurden. For additional copies of New Glass Review, Zusatzliche Exemplare des New Glass Review please contact: konnen angefordert werden bei: The Corning Museum of Glass Sales Department One Museum Way Corning, New York 14830-2253 (607) 937-5371 All rights reserved, 1989 Alle Rechtevorbehalten, 1989 The Corning Museum of Glass The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 14830-2253 Corning, New York 14830-2253 Printed in Dusseldorf FRG Gedruckt in Dusseldorf, Bundesrepublik Deutschland Standard Book Number 0-87290-119-X ISSN: 0275-469X Library of Congress Catalog Card Number Aufgefuhrt im Katalog der KongreB-Bucherei 81-641214 unter der Nummer 81-641214 Table of Contents/lnhalt Page/Seite Jury Statements/Statements der Jury 4 Artists and Objects/Kunstler und Objekte 10 Bibliography/Bibliographie 30 A Selective Index of Proper Names and Places/ Verzeichnis der Eigennamen und Orte 53 er Wunsch zu verallgemeinern scheint fast ebenso stark ausgepragt Jury Statements Dzu sein wie der Wunsch sich fortzupflanzen. Jeder mochte wissen, welchen Weg zeitgenossisches Glas geht, wie es in der Kunstwelt bewer- tet wird und welche Stile, Techniken und Lander maBgeblich oder im Ruckgang begriffen sind. Jedesmal, wenn ich mich hinsetze und einen Jurybericht fur New Glass Review schreibe (dies ist mein 13.), winden he desire to generalize must be almost as strong as the desire to und krummen sich meine Gedanken, um aus den tausend und mehr Dias, Tprocreate. -

Life on Air: Memoirs of a Broadcaster PDF Book

LIFE ON AIR: MEMOIRS OF A BROADCASTER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sir David Attenborough | 448 pages | 01 Jul 2011 | Ebury Publishing | 9781849900010 | English | London, United Kingdom Life on Air: Memoirs of a Broadcaster PDF Book And not all of us can do that, even given the chance; I, for one, most certainly could not, given my insects phobia. Featuring 60 superb color plates, this is an easy-to-use photographic identification guide to the You'll like it if you like Sir. In his compelling autobiography, Michael McIntyre reveals all. I will defiantly listen to another of his marvellous books. For additional information, see the Global Shipping Program terms and conditions - opens in a new window or tab This amount includes applicable customs duties, taxes, brokerage and other fees. Why on earth you would think they are quartz crystals? Attenborough's storytelling powers are legendary, and they don't fail him as he recounts how he came to stand in rat-infested caves in Venezuela, confront wrestling crocodiles, abseil down a rainforest tree in his late sixties, and wake with the lioness Elsa sitting on his chest. This is a big old book, or at least it felt it to me. He was knighted in and now lives near London. As a student of film it is a veritable history of broadcast television and practical film making. If you are not happy then neither are we. Rediscover the thrills, grandeur, and unabashed fun of the Greek myths. David Attenborough is a giant of natural history and this book charting his many TV series brought home to me just what a contribution he's made to our understanding of the natural world. -

Aggression and Symbols of Power

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 10-14-1990 Aggression and symbols of power Karen Kuhn Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Kuhn, Karen, "Aggression and symbols of power" (1990). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rochester Institute of Technology A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Fine and Applied Arts in Candidacy for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Aggression and Symbols of Power by Karen Kuhn 10.14.90 Approvals Advisor: Mark Stanitz Date: /.¥yl1l. Associate Advisor: Leonard Urso Date: /:.~/(?/?~ . Associate Advisor: David Dickenson Date: I.~/~.f/..~(J. Special Assistant to the Dean for Graduate Affairs: Philip Bornarth Date: !~E(!1.9. Peter Grofeeler I, Karen V. Kuhn, prefer to be contacted each time a request for reproduction is made. I can be reached at the following address: 10 Valdepenas Lane Clifton Park. NY 12065 Date: 90.10.14 Aggression and Symbols of Power Abstract: Weapons are one of the oldest and most significant forms of artifacts, occurring in virtually all human cultures. Weapons and their technology often determine power structures, not only by brute force of arms, but by long standing respect to ritual aggression. In many cultures, weapons have become abstracted and formalized to become symbols of power and authority, as in a ruler 's scepter, which is a glorified war club. -

Annual Report 2010 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2010 CONTENTS DIRECTOR’S LETTER 3 –4 PRESIDENT’S LETTER 6 ACQUISITIONS 7–13 EXHIBITION SCHEDULE 14 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 15 VOLUNTEER HIGHLIGHTS 16 – 19 2010 DONOR LISTINGS 21 – 28 ART MATTERS ENDOWMENT AND CAPITAL CAMPAIGN DONOR LISTINGS 29 – 35 FROM THE DIRECTOR Photograph by Greg Bartram. Looking back, 2010 was the year of the hard hat. I can’t We took our innovative Art Around Town show to count the number of times I donned my hard hat, which community locations throughout Central Ohio. From hung on a hook in my office, to see the changes taking November of 2009 through December of 2010, more shape in the galleries; to give a donor a tour; to select than 1,300 people enjoyed an experience with an original a new paint color; to test the acoustics in the work of art from our collection, a docent talk, an art Cardinal Health Auditorium; to try out the new cork project, games, and other family-friendly activities. floor in the American Electric Power Foundation Ready Room; or to revel in the glorious new skylight in Derby The community embraced our second Summer Fun Court. We built a renovated Elizabeth M. and Richard initiative, which offered free admission and enhanced M. Ross Building. We built a dynamic, new Center for programming in July and August. Each day, a diverse Creativity. We built new experiences for visitors. And audience joined us for tours, games, art projects and the we built a vision for the future. family-friendly Fur, Fins and Feathers exhibition, which highlighted works from our collection that depict ani - As we were designing our vision for the future, we were mals. -

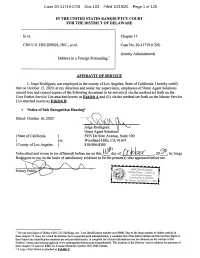

Case 20-11719-CSS Doc 103 Filed 10/19/20 Page 1 of 126 Case 20-11719-CSS Doc 103 Filed 10/19/20 Page 2 of 126

Case 20-11719-CSS Doc 103 Filed 10/19/20 Page 1 of 126 Case 20-11719-CSS Doc 103 Filed 10/19/20 Page 2 of 126 EXHIBIT A Case 20-11719-CSS Doc 103 Filed 10/19/20 Page 3 of 126 Exhibit A Core Parties Service List Served as set forth below Description Name Address Email Method of Service Counsel to the Wilmington Trust, NA Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer LLP 250 West 55th Street [email protected] Email New York, NY 10019 [email protected] First Class Mail [email protected] Notice of Appearance and Request for Notices ‐ Counsel to Ad Hoc Ashby & Geddes, P.A. Attn: William P. Bowden [email protected] Email Committee of First Lien Lenders 500 Delaware Ave, 8th Fl P.O. Box 1150 Wilmington, DE 19899‐1150 Notice of Appearance and Request for Notices Ballard Spahr LLP Attn: Matthew G. Summers [email protected] Email Counsel to Universal City Development Partners Ltd. and Universal Studios 919 N Market St, 11th Fl Licensing LLC Wilmington, DE 19801 Counsel to the Financial Advisors BCF Business Law Attn: Claude Paquet, Gary Rivard [email protected] Email 1100 René‐Lévesque Blvd W, 25th Fl, Ste 2500 [email protected] First Class Mail Montréal, QC H3B 5C9 Canada Governmental Authority Bernard, Roy & Associés Attn: Pierre‐Luc Beauchesne pierre‐[email protected] Email Bureau 8.00 [email protected] First Class Mail 1, rue Notre‐Dame Est Montréal, QC H2Y 1B6 Canada Notice of Appearance and Request for Notices Buchalter, PC Attn: Shawn M. -

Christopher Ries: Sculptor in Four Dimensions (Length, Width, Height and Light) by Debbie Tarsitano

Christopher Ries: Sculptor in Four Dimensions (Length, Width, Height and Light) By Debbie Tarsitano “We all think about light. Glass embodies it. Glass is the one medium that gathers, focuses, amplifies, transmits, filters, diffuses and reflects it. It is the quintessential medium for light. I see it all on a symbolic level.” -- Christopher Ries Many artists like William Morris and Dino Rosin sculpt hot glass by gathering and shaping molten crystal. Hot sculpting is quick and intense, and produces flowing, free-form sculptures. In contrast, sculptors like Christopher Ries, Jonathan Kuhn and Steven Weinberg, who work cold glass, sculpt their material in a more leisurely and deliberate manner to produce defined, precise forms. The hot glass sculptors must work quickly, while sculptors of cold glass may revisit and change their designs over time. Christopher Ries, a master sculptor of cold glass, employs the discipline of “classical reductive sculpture.” Ries hand carves massive blocks of glass to create his exterior shapes by taking material away. His work is physically and emotionally demanding, because his sculpting must liberate a dynamic, striking work of art from a lifeless block of crystal. However, the fact that Ries’ sculptural material is some of the purest optical crystal manufactured in the world today, lets him add an additional presence to his work. Ries’ use of light as a primary material for creating art sets his work apart from other hot and cold glass sculptors. His designs harness the energy of light to drive illusions. Visions of living flowers and soaring gothic arches inhabit the interior of his sculptures. -

UNESCO Kalinga Prize Winner – 1981 Sir David Attenborough

Glossary on Kalinga Prize Laureates UNESCO Kalinga Prize Winner – 1981 Sir David Attenborough A British Legend of Science Serials, Britain’s Best Known Natural History Film Maker & Arguably the World’s Foremost Television Naturalist [Born: May 8, 1926 in London, England …………] Mankind has Probably done more damage to the earth in the 20th Century than in all of Previous human history. ... David Attenborough “If we [humans] disappeared over right, the world would Probably be better off.” The Daily Telegraph, London, 12, November, 2005 … David Atenborough “It seems to me that natural world is the greatest source of excitement, the greatest source of visual beauty; the greatest source of intellectual interest . It is the greatest source of so much in life that makes life worth living.” … David Attenborough. 1 Glossary on Kalinga Prize Laureates David Attenborough : A Biographical Profile World’s Best Known Broadcasters, Humanists and Naturalists Born : May 8, 1926 London, England Residence : Richmond, London Nationality : British Field : Naturalist Alma mater : Clare College, Cambridge (Natural Sciences) Notable Prizes : Order of Merit, Order of the Companions of Honour, Royal Victorian Order, Order of the British Empire, Fellow of the Royal Society Sir David Frederick Attenborough, OM, CH, CVO, series is in production. He is also a former senior CBE, FRS (born on May 8, 1926 in London, England) manager at the BBC, having served as controller of is one of the world’s best known broadcasters and BBC2 and director of programming for BBC naturalists. Widely considered one of the pioneers Television in the 1960s and 1970s. of the nature documentary, his career as the He is the younger brother of director and actor respected face and voice of British natural history Richard Attenborough. -

Download New Glass Review 07

The Corning Museum of Glass NewGlass Review 7 The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 1986 Objects reproduced in this annual review Objekte, die in dieser jahrlich erscheinenden were chosen with the understanding Zeitschrift veroffentlicht werden, wurden unter that they were designed and made within der Voraussetzung ausgewahlt, dal3 sie the 1985 calendar year. innerhalb des Kalenderjahres 1985 entworfen und gefertigt wurden. For additional copies of New Glass Review Zusatzliche Exemplare der New Glass Review please contact: konnen angefordert werden bei: Sales Department The Coming Museum of Glass Corning, New York 14831 (607)937-5371 All rights reserved, 1986 Alle Rechte vorbehalten, 1986. The Corning Museum of Glass The Corning Museum of Glass Corning, New York 14831 Corning, New York 14831 Printed in Dusseldorf FRG Gedruckt in Dusseldorf, Bundesrepublik Deutschland Standard Book Number 0-: 1-115-7 ISSN: 0275-469X Library of Congress Catalog Card Number Aufgefiihrt im Katalog der KongreB-Bucherei 81-641214 unter der Nummer 81-641214 Table of Contents/lnhalt Page/Seite Jury Statements and Comments/Statements und Kommentarder Jury 4 Artists and Objects/Kunstler und Objekte 9 Bibliography/Bibliographie 31 Galleries and Museums/Galerien und Museen 52 Countries Represented/Vertretene Lander 55 Die zeitgenossische Glasszene wird einfach immer besser; und Vielfalt, Jury Statements Originalitat und Qualitat nehmen mit jedem New Glass Review zu. Der hubsche Anblick von Glas mit all seinen optischen Effekten macht subtiler- en - und haufig auch tiefgreifenden - Ideen Platz, von denen das astheti- The contemporary glass scene just gets better and better. There is more sche Potential unseres Materials mehr und mehr durchdrungen wird. -

2009 Winter.Pub

The Bates Bulletin SERIES X VOL 1 WINTER 2009 NUMBER 4 Henry Bates and a Brick Wall State of Illinois. "In indenture made this 10th day of April 1842 between Stephen Mack and Hononegah his For Dr. Charles & Sheila Bates wife of the first part and Henry N. Bates of the second By Sandy, Sheila & Dr. Charles Bates part in the County of Winnebago, Illinois " for three lots at fifty dollars, where Henry N. set up shop as a shoe Dr. Charles Bates long believed his line was that of maker. James of Dorchester, Mass. But when he and his Nephew took the DNA test they matched each other, This is all we have as clues to Henry's life but it didn't but did not match any of the other Bates Lines. Just stop us from trying to find others. Research failed to no clues have come up, who the parents of this Henry find a connection to the other Bates' living in Damas- Bates are. cus as neighbors. It was the same situation when Henry moved to Macktown, where about five miles Dr. Charles wife Pauline (Barta) Bates is descended down the road in the village of Shirland lived more from the Virginia Bates: John--George--John--John-- Bates'. I did more extended research on these Bates John--Hannah (Ancestor of Pauline). while doing work on my son in law's Robinson family and along the way realized there was a family tie to Sheila Bates writes the following and submitted him through his family lines of Jewell and Orcutt, with pictures, with the article. -

Received by the Regents February 19, 2015

The University of Michigan Office of Development Unit Report of Gifts Received 4 Year Report as of Janaury 31, 2015 Transactions Dollars Fiscal Fiscal Fiscal Fiscal Fiscal Year Ended June 30, YTD YTD Fiscal Year Ended June 30, YTD YTD UNIT 2012 2013 2014 Janaury 31, 2014 Janaury 31, 2015 2012 2013 2014 Janaury 31, 2014 Janaury 31, 2015 Taubman Arch & Urban 796 765 790 564 607 $ 1,259,779 $ 841,056 $ 2,433,235 $ 830,480 $ 665,234 Art and Design 565 519 580 352 392 642,764 9,134,128 1,074,478 961,688 936,494 Ross School of Business 8,077 8,581 7,941 4,915 4,850 17,308,758 15,696,393 21,354,723 15,343,689 17,487,827 Dentistry 1,882 1,844 1,923 1,288 1,214 2,047,740 2,131,364 3,596,109 1,292,419 3,320,641 Education 2,860 2,821 2,561 1,810 1,836 5,330,851 5,320,854 2,846,472 1,826,681 3,475,982 Engineering 7,751 7,449 7,947 5,032 5,192 24,338,632 19,380,422 31,842,383 26,543,636 20,634,378 School of Information 1,087 1,552 1,494 637 694 531,158 4,558,058 2,280,265 1,206,552 571,910 Kinesiology 920 603 953 658 430 479,454 748,258 690,459 353,189 828,075 Law School 5,772 5,733 5,631 4,004 4,208 33,375,415 17,579,895 12,888,048 9,585,829 9,609,246 LSA 15,813 15,574 16,070 11,361 11,335 24,420,095 35,202,954 36,239,451 21,794,343 26,345,039 School of Music, Theater & Dance 3,757 3,893 3,881 2,871 3,011 8,704,071 10,631,842 5,728,305 3,324,531 6,167,965 Natural Resources & Env. -

Films About the Pacific Islands

A GUIDE TO 'FILMS ABOUT THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Compiled by Judith D. Hamnett Workinl Paper Series Pacific bland. Studies Pro,ram Center for A.ian and Pacific Studies Univeraity of Hawaii at Manoa This guide to films about the Pacific was developed out of a sense that such an item was sorely needed. The chore took longer than anticipated, and it was completed only with a major effort and considerable patience on the part of Ms. Judith D. Hamnett. We intend to update the guide periodically, and we urge readers to pay special attention to the last paragraph of Ms. Hamnett's introduction. New items, corrections, and other relevant information received from readers will be incorporated into future editions. We intend to keep the guide in print and available for the asking, and such input will be appreciated and help improve its quality. Robert C. Kiste, Director Pacific Islands Studies Program Center for Asian and Pacific Studies University of Hawaii at Manoa Honolulu, Hawaii A GUIDE TO FILMS ABOUT THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Compiled by Judith D. Hamnett Pacific Islands Studies Program University of Hawaii 1986 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Lending Collections ••••••••••••••••• 3 Abbreviations Used for Producers/Distributors •••• 8 Section I.: Films and Videocassettes about the Pacific Islands, Excluding Hawaii ••••••• 14 Section II. Films and Videocassettes about Hawaii ••• . • • • 59 Section III. Films about the Pacific Islands Available Outside of the U.S •••••••••••• 110 1 A GUIDE TO FILMS ABOUT THE PACIFIC ISLANDS INTRODUCTION This gUide to films about the Pacific Islands was prepared during the summers of 1985 and 1986. During that period a number of important films were added to the University of Hawaii's film collection and are included here. -

Ries Resume April 2014 Revised

Christopher! Ries Christopher Ries (1952) received a BFA from the Ohio State University and an MFA from the University of Wisconsin at Madison. While at Madison, he was personal assistant to Harvey K. Littleon, who is considered to be the father of the 20th century Studio Glass Movement. Mr. Ries has collaborated with Schott North America since 1982, and in 1986 was offered the title Artist in Residence at the Duryea facility, an !honorary position he maintains today. !His works are highly and widely acclaimed for their simple elegance and artistic power. !EDUCATION !2010 Doctor of Humane Letters (Honorary), Misericordia University, Dallas, PA 1978 Master of Fine Arts in glass, University of Wisconsin, Madison !1975 Bachelor of Fine Arts in ceramics and glass, The Ohio State University !ONE PERSON EXHIBITIONS !2012 Crystal Clear, Stewart Fine Art, Boca Raton, Florida !2010 Christopher Ries: Gallery of Modern Masters, Sedona, Arizona ! Christopher Ries: Westbrook Gallery, Carmel by the Sea, California ! Christopher Ries: Primavera Gallery, Ojai, California ! Christopher Ries: Hawk Galleries, Columbus, Ohio ! Glass & Light Show, Wayne Art Center, Wayne, PA 2009 Christopher Ries: Guiding Light, Pauly Friedman Art Gallery, Misericordia University, ! Dallas, Pennsylvania 2008! Christopher Ries: Wiford Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico !2007 Christopher Ries: Optical Reflections, Pismo Fine Art Glass, Aspen Colorado Christopher Ries: Guiding Light, Hawk Galleries, Columbus Ohio 2006 Christopher Ries: Master in Glass, The Ohio State University Faculty Club, Columbus, ! Ohio ! Photonics West, San Jose, California. Also 2005, 2004, 2003, 2002, 2001, 2000, 1999 !2005 Etienne and Van Den Doel Expressive Glass Art, Oisterwijk, The Netherlands ! Davis and Cline Gallery, Ashland, Oregon ! Thomas R.