20160311 NO REFILL Baseline Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The eighth-century revolution Version 1.0 December 2005 Ian Morris Stanford University Abstract: Through most of the 20th century classicists saw the 8th century BC as a period of major changes, which they characterized as “revolutionary,” but in the 1990s critics proposed more gradualist interpretations. In this paper I argue that while 30 years of fieldwork and new analyses inevitably require us to modify the framework established by Snodgrass in the 1970s (a profound social and economic depression in the Aegean c. 1100-800 BC; major population growth in the 8th century; social and cultural transformations that established the parameters of classical society), it nevertheless remains the most convincing interpretation of the evidence, and that the idea of an 8th-century revolution remains useful © Ian Morris. [email protected] 1 THE EIGHTH-CENTURY REVOLUTION Ian Morris Introduction In the eighth century BC the communities of central Aegean Greece (see figure 1) and their colonies overseas laid the foundations of the economic, social, and cultural framework that constrained and enabled Greek achievements for the next five hundred years. Rapid population growth promoted warfare, trade, and political centralization all around the Mediterranean. In most regions, the outcome was a concentration of power in the hands of kings, but Aegean Greeks created a new form of identity, the equal male citizen, living freely within a small polis. This vision of the good society was intensely contested throughout the late eighth century, but by the end of the archaic period it had defeated all rival models in the central Aegean, and was spreading through other Greek communities. -

Greece, 1821-1941. ~ Ebook Greece, 1821-1941

- < Greece, 1821-1941. ~ eBook Greece, 1821-1941. American Friends of Greece - The Short Description: - - Poland -- History -- 1980-1989 -- Sources. Poland -- History -- 1945-1980 -- Sources. Greece.Greece, 1821-1941. -Greece, 1821-1941. Notes: Title in Greek on cover. This edition was published in 1941 Filesize: 48.64 MB Tags: #Rochester #Genealogy #(in #Monroe #County, #New #York) Monroe County NY Church Records Athens, Athens School of Fine Arts, Nikiforos Lytras 1833-1933 retrospective exhibition, April 1933, no. The Short For more information on how to locate offline newspapers, see our article on. During the Greek War of Independence 1821—1827 from the Ottomans—which had a nationalistic and liberal character—and for the first decades after the liberation, a number of liberal French-educated politicians and scholars attempted unsuccessfully to introduce the Napoleonic Civil Code or some clone of it as the Greek Civil Code. Includes declassified records returned to file after February 2016 release by Hoover. Rochester Genealogy (in Monroe County, New York) USA: City of Los Angeles. PDF from the original on 29 November 2014. Monroe County NY Church Records Cemetery Transcriptions from NEHGS Billion Graves WorldCat Cemetery Transcriptions from NEHGS Cemetery Transcriptions from NEHGS WorldCat Cemetery Transcriptions from NEHGS Find a Grave US Gen Web Billion Graves Family History Library Family History Library Family History Library US Gen Web Billion Graves Interment US Gen Web WorldCat Find a Grave Billion Graves Interment Billion -

![Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements [Full Text, Not Including Figures] J.L](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6957/greek-color-theory-and-the-four-elements-full-text-not-including-figures-j-l-1306957.webp)

Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements [Full Text, Not Including Figures] J.L

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements Art July 2000 Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgc Benson, J.L., "Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgc/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire ABOUT THIS BOOK Why does earlier Greek painting (Archaic/Classical) seem so clear and—deceptively— simple while the latest painting (Hellenistic/Graeco-Roman) is so much more complex but also familiar to us? Is there a single, coherent explanation that will cover this remarkable range? What can we recover from ancient documents and practices that can objectively be called “Greek color theory”? Present day historians of ancient art consistently conceive of color in terms of triads: red, yellow, blue or, less often, red, green, blue. This habitude derives ultimately from the color wheel invented by J.W. Goethe some two centuries ago. So familiar and useful is his system that it is only natural to judge the color orientation of the Greeks on its basis. To do so, however, assumes, consciously or not, that the color understanding of our age is the definitive paradigm for that subject. -

ARCL 0066: the Emergence of Bronze Age Aegean States

UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ARCL 0066: The Emergence of Bronze Age Aegean States 2019-2020 - Term 2 Undergraduate Year 2-3 option, 15 credits Coursework deadlines: Monday 21st February 2020, Monday 3rd April 2020 (TBC) Co-ordinator: Dr. Borja Legarra Herrero [email protected], Room 106 1 1. OVERVIEW Short Description This course provides a survey of Aegean prehistory from The Neolithic until c. 1500-1400 BC. It focuses on the origins of complex societies during the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC and the dynamics of the Minoan palatial societies that followed. It provides a broadly chronologically overview of the region’s long-term transformations and the remarkably rich data (material, iconographic and archival) on which interpretations are based. It encourages a thematic treatment, within a theoretically informed, problem-oriented framework, of major processes including: state formation, elaboration and collapse; production, trade and consumption in and beyond the Aegean; archaeologies of cult and death; the interpretation of symbols and images; and the place of the prehistoric Aegean within the wider Mediterranean and Near Eastern world. The course equally emphasises the need to understand how interpretations and data collection strategies have developed, and the impact this has had on accounts of Aegean prehistory. Week-by-week summary (lectures are Monday, 10-12.00, in Room 410). Date Session Topic 13 Jan. 1 Introduction: Aegean space, time and environments. 2 Is ‘Minoan’ the right word? Biases in the study of the Aegean Bronze Age. 20 Jan. 3 Neolithics: taming of a fragmented landscape. 4 Seminar: Fieldwork in the Aegean: Archaeologists’ paradise? 27 Jan. -

Timeline of the Peloponnesian

CSTS119: CULTURE & CRISIS IN THE GOLDEN AGE OF ATHENS Timeline of Athens during the Peloponnesian War POLITICAL & MILITARY EVENTS CULTURAL EVENTS 432 Revolt of Potidaea. The ‘Megarian decree’ passed at Athens. Phidias completes the Parthenon frieze and the pediments Peloponnesian League declares for war. of the Parthenon; he dies soon after this date. Empedocles dies. Athens bans teaching of atheism. 431 First year of the Peloponnesian War.—The Archidamian Thucydides begins work on Histories. Euripides: Medea War (431-421). Theban attack on Plataea (March). First (3rd), <Philoctetes, Dictys> Peloponnesian invasion of Attica (May) under Spartan Archidamus. Athens wins Soilion and Cephallenia; takes Thronion and Atalanta: expels Aeginetans from Aegina. 430 Plague strikes Athens (430-427). Second invasion of Attica. Euripides: Heraclidae. Stesimbrotus writes critique of Expedition of Pericles to Argolis and failure at Epidaurus. Athenian power, On Themistocles, Thucydides, and Pericles deposed from strategia, tried, fined, and Pericles; he will also compose important works on reappointed strategos. Phormio operates in the west. Homeric allegory and Orphic practices. The important Sicilian historian Philistus of Syracuse born. 429 Capitulation of Potidaea; Pericles reinstated and dies, who Sophocles' Oedipus Rex and Trachiniae after this date (?). for more than, thirty years has guided the policy of Athens. First performance of a comedy by Eupolis. Lysias moves Peloponnesians besiege Plataea. Sea-victories of Phormio to Thurii after death of father Cephalus, whose house is in the Corinthian Gulf. the setting for Plato’s Republic 428 Third invasion of Attica. Revolt of Mytilene from Athens. Euripides: Hippolytus (1st). Plato and Xenophon born Introduction of war tax (eisphora). -

Kalaureia 1894: a Cultural History of the First Swedish Excavation in Greece

STOCKHOLM STUDIES IN ARCHAEOLOGY 69 Kalaureia 1894: A Cultural History of the First Swedish Excavation in Greece Ingrid Berg Kalaureia 1894 A Cultural History of the First Swedish Excavation in Greece Ingrid Berg ©Ingrid Berg, Stockholm University 2016 ISSN 0349-4128 ISBN 978-91-7649-467-7 Printed in Sweden by Holmbergs, Malmö 2016 Distributor: Dept. of Archaeology and Classical Studies Front cover: Lennart Kjellberg and Sam Wide in the Sanctu- ary of Poseidon on Kalaureia in 1894. Photo: Sven Kristen- son’s archive, LUB. Till mamma och pappa Acknowledgements It is a surreal feeling when something that you have worked hard on materi- alizes in your hand. This is not to say that I am suddenly a believer in the inherent agency of things, rather that the book before you is special to me because it represents a crucial phase of my life. Many people have contrib- uted to making these years exciting and challenging. After all – as I continu- ously emphasize over the next 350 pages – archaeological knowledge pro- duction is a collective affair. My first heartfelt thanks go to my supervisor Anders Andrén whose profound knowledge of cultural history and excellent creative ability to connect the dots has guided me through this process. Thank you, Anders, for letting me explore and for showing me the path when I got lost. My next thanks go to my second supervisor Arto Penttinen who encouraged me to pursue a Ph.D. and who has graciously shared his knowledge and experiences from the winding roads of classical archaeology. Thank you, Arto, for believing in me and for critically reviewing my work. -

The Symposium in Context (Hesp.Suppl. 46): Sample

the symposium in context the symposium Kathleen Lynch is Associate Profes- This book presents the first well- sor in the Department of Classics at the preserved set of sympotic pottery recov- University of Cincinnati. She has worked “The major objectives of the study are excellent ered from a household near the Athenian on sites in Italy, Greece, Albania, and ones, and reflect the best current directions of Agora. The deposit contains utilitarian Turkey. pottery studies . [They] demonstrate deci- and fine-ware pottery, nearly all the -fig ured pieces of which are forms associated sively how much greater the whole is than the with communal drinking. The archaeo- sum of its parts.” logical context allows the iconography of the figured wares to be associated — Nicholas D. Cahill, Professor of Art History, with a specifically Athenian worldview, University of Wisconsin-Madison in contrast to Attic figured pottery made the symposium for export markets. Since it comes from in context a single house, the pottery reflects the purchasing patterns and thematic prefer- Pottery from a Late Archaic House ences of the homeowner. The multifac- near the Athenian Agora eted approach adopted here shows that meaning and use are inherently related, and that through archaeology we can restore a context of use for a class of objects frequently studied in isolation. “[This book] contributes valuable information about what an Athenian family was actually using, which helps us make inferences about their behavior. Readers will find it useful and interesting to examine a household assem- blage, especially to be able to study an Athenian house’s well-preserved assortment of pottery KATHLEEN M. -

The Appropriation of Death in Classical Athens

The Appropriation of Death In Classical Athens Alexandra Donnison Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Classics Victoria University of Wellington August 2009 δ κρβη θνατο Cover picture: Anavysos. Kouros from tomb of Kroisos. c. 530 B.C.E. NM, Athens. 3851. Hurwit (2007b). Fig. 35. 2 Acknowledgements To my parents, who have been there every step of the way, without their guidance and support - and especially their sense of humour – this would not have been possible. I would also like to express thanks to my supervisor, Matthew Trundle, for his time, knowledge and guidance. Finally, but not least, I wish to express my deepest gratitude to my friends who spent countless hours proof reading this thesis, and who in the process learnt more about Ancient Greek burial customs than they ever felt necessary. Note on translations: All translations are taken from the Loeb, unless otherwise stated. 3 Contents Page Abstract……………………………………………………………………….5 List of Figures...................................................................................................7 Introduction ......................................................................................................9 Chapter One: The Change in Burial Practices Between the Archaic and Classical Periods .......................................................................................19 Chapter Two: Why the Change in Funeral Practices Took Place ...................58 Chapter Three: The Re-emergence of the Grave Monument ..........................92 -

ATHENS and the CYCLADES This Page Intentionally Left Blank Athens and the Cyclades

ATHENS AND THE CYCLADES This page intentionally left blank Athens and the Cyclades Economic Strategies 540–314 BC BRIAN RUTISHAUSER 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries # Brian Rutishauser 2012 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2012 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available ISBN 978–0–19–964635–7 Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn To my parents, Kurt and Eleanor Rutishauser This page intentionally left blank Preface The island group known as the Cyclades offers great potential to historians of Greek antiquity, yet this potential has only been slightly explored. -

The Persians Entire First Folio

First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide The Persians by Aeschylus new version by Ellen McLaughlin directed by Ethan McSweeny April 4—May 21, 2006 First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide Table of Contents Page Number Welcome to the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s production ofThe Persians by Aeschylus! A Brief History of the Audience…………………….1 Each season, the Shakespeare Theatre Company presents five plays by William Shakespeare and About the Playwright other classic playwrights. The Education On Aeschylus..….……………………..………………………3 Department continues to work to deepen The History of Greek Drama….……………………….4 understanding, appreciation and connection to classic theatre in learners of all ages. One About the Play approach is the publication ofFirst Folio: Teacher Synopsis of The Persians…………...……………………6 Curriculum Guides. The Persian Wars….……………………..…………..……..7 Rise & Fall—Timeline of the Persian In the 2005•06 season, the Education Empire………………………..…………………………9 Department will publishFirst Folio: Teacher The Body Politic……………………….........................11 Curriculum Guides for our productions ofOthello, Interview with the Adaptor: The Comedy of Errors, Don Juan, The Persians Ellen McLaughlin……………………………...13 and Love’s Labor’s Lost. The Guides provide information and activities to help students form Classroom Connections a personal connection to the play before • Before the Performance…………………...………15 attending the production at the Shakespeare Choral Performance Activity Theatre Company. First Folio guides are full of Timeline of Recent History—Compare to material about the playwrights, their world and Athens and Persia the plays they penned. Also included are Who Writes History? Recording World approaches to explore the plays and Events productions in the classroom before and after Why Do This Play Today? the performance. -

A Point in Time Malcolm H Wiener

36 A point in time Malcolm H Wiener Chronology is the spine of history. I. INTRODUCTION 1525 BC for the Theran eruption. In 1984, an article in the journal Nature6 reported that the long-lived The publication in 1989 of Aegean Bronze Age bristlecone pines of California showed a serious frost Chronology (henceforth ABAC), the monumental work year at 1626 BC, and suggested that this might be related by Peter Warren and Vronwy Hankey, marked a to the eruption ofThera. Peter Warren promptly replied decisive moment in the study of Aegean prehistory. with an article showing that many major eruptions had Subsequent discoveries have led to minor modifications left no record in tree rings.' In addition, tree rings to the chronology proposed, amounting to no more sometimes indicate the possibility of an eruption when years at any BC than 25 point after 1450 in the Late none was reported in that year. Bronze Age.2 I have contributed to this genre myself, The 1628-1626 BC proposition received an contending that the Late Helladic (Mycenaean) IIIA2 additional impetus when it was initially reported that period required a lengthening in light of a reconsidera- tree rings at Porsuk, a Hittite site near the Cilician Gates tion of the Mycenaean pottery from the datable Amarna in Turkey, 840 km downwind from Thera, also showed deposit and other Egyptian contexts. I also noted the a major event within those years.' Anatolian junipers large amount and wide distribution of LH IIIA2 do not live for thousands of years as do California and pottery over the Mediterranean -

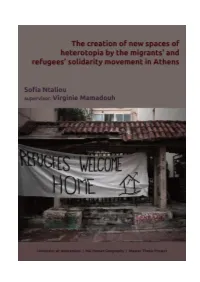

The Creation of New Spaces of Heterotopia by the Migrants' And

The creation of new spaces of heterotopia by the migrants’ and refugees’ solidarity movement in Athens Source of the image in the cover page: Panagiotis Maidis (2015, September 28). Anarchists Have Taken Over a Building in Athens to House Refugees Vice [online] Available at: https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/xd7vj4/anarchists-have-taken-over-a-building-in-athens- to-house-refugees-876. [Accessed 25/06/2017] Design of cover page: Emmy I. Karimali 1 | P a g e The creation of new spaces of heterotopia by the migrants’ and refugees’ solidarity movement in Athens GSSS GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MASTER HUMAN GEOGRAPHY Thesis 2017, June 26 Sofia Ntaliou -11176342- [email protected] Supervisor: Virginie Mamadouh Second Assessor: Inge van der Welle 2 | P a g e The creation of new spaces of heterotopia by the migrants’ and refugees’ solidarity movement in Athens 3 | P a g e Contents Abstract................................................................................................................................. 6 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1: Introduction .......................................................................................................... 8 Chapter 2: Geographies of social movements ..................................................................... 10 2.1. Social Movements as a mean to social change ........................................................ 10 2.2. The importance of space .........................................................................................