The Appropriation of Death in Classical Athens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democracy and Institutional Change

European Research Studies, Volume X, Issue (1-2) 2007 Democracy and institutional change By Nicholas Kyriazis1 Abstract: The present essay analyses decision making procedures concerning economic issues such as the choice of public goods in the prototype democracy, Ancient Athens of the fourth century BC (the “Age of Demosthenes”). It analyses the link between political democracy, “economic” democracy, the emergence of new institutions and the finance of public goods like defence, education and “social security”. The prototype political democracy was advanced in questions of public administration, finance and institutions, on which political democracy was based. The paper concludes with some proposals as to what we could “learn” from the workings of “economic democracy” that is relevant for today’s democracies. Keywords: Hospital efficiency, productivity, health. JEL Classification: I11, I12, I18 1. Introduction There is a vast literature on the history, politics, warfare the arts etc. of the ancient Athenian democracy, which is considered the prototype and the origin of Western democracies.1 Much less attention has been paid till recently on the economics of the Athenian state, which is actually astonishing, since the Athenian state could not have developed its advanced political institutions without a sound economic basis, and advanced institutions and organisations, as I will purport to analyse later on in the present essay. (Kyriazis and Zouboulakis 2004, Kyriazis and Halkos 2005, Cohen 1997, Gabrielsen 1994). The Athenian democracy -

4.5 Mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate. Part of the Variable Angle Periarticular Plating System

4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate. Part of the Variable Angle Periarticular Plating System. Technique Guide Table of Contents Introduction 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plates 2 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate System 4 AO Principles 5 Indications 6 Surgical Technique Preparation 7 Reduce Articular Surface 11 Insert Plate 12 Insert Screw in Central Plate Head Hole 20 Option A: 5.0 mm Solid Variable Angle Screw 20 Option B: 5.0 mm Cannulated Variable Angle Screw 23 Insert Screws in Surrounding Plate Head Holes 26 Option A: 5.0 mm Solid Variable Angle Screws 26 Option B: 5.0 mm Cannulated Variable Angle Screws 30 Insert Screws in Plate Shaft 32 Option A: 4.5 mm Cortex Screws 32 Option B: 5.0 mm Solid Variable Angle Screws 34 Option C: 5.0 mm Cannulated Variable Angle Screws 37 Remove Instruments 40 Product Information Implants 41 Instruments 43 Set Lists 45 Image intensifier control 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate Technique Guide Synthes 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plates. Part of the Variable Angle Periarticular Plating System. The Synthes 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate is part of the VA-LCP Periarticular Plating System which merges variable angle locking screw technology with conventional plating techniques. The 4.5 mm VA-LCP Curved Condylar Plate System has many similarities to standard locking fixation methods, with a few important improvements. Variable angle locking screws provide the ability to create a fixed-angle construct while also allowing the surgeon the freedom to choose the screw trajectory before “fixing” the angle of the screw. -

Who Freed Athens? J

Ancient Greek Democracy: Readings and Sources Edited by Eric W. Robinson Copyright © 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd The Beginnings of the Athenian Democracv: Who Freed Athens? J Introduction Though the very earliest democracies lildy took shape elsewhere in Greece, Athens embraced it relatively early and would ultimately become the most famous and powerful democracy the ancient world ever hew. Democracy is usually thought to have taken hold among the Athenians with the constitutional reforms of Cleisthenes, ca. 508/7 BC. The tyrant Peisistratus and later his sons had ruled Athens for decades before they were overthrown; Cleisthenes, rallying the people to his cause, made sweeping changes. These included the creation of a representative council (bode)chosen from among the citizens, new public organizations that more closely tied citizens throughout Attica to the Athenian state, and the populist ostracism law that enabled citizens to exile danger- ous or undesirable politicians by vote. Beginning with these measures, and for the next two centuries or so with only the briefest of interruptions, democracy held sway at Athens. Such is the most common interpretation. But there is, in fact, much room for disagree- ment about when and how democracy came to Athens. Ancient authors sometimes refer to Solon, a lawgiver and mediator of the early sixth century, as the founder of the Athenian constitution. It was also a popular belief among the Athenians that two famous “tyrant-slayers,” Harmodius and Aristogeiton, inaugurated Athenian freedom by assas- sinating one of the sons of Peisistratus a few years before Cleisthenes’ reforms - though ancient writers take pains to point out that only the military intervention of Sparta truly ended the tyranny. -

'Made in China': a 21St Century Touring Revival of Golfo, A

FROM ‘MADE IN GREECE’ TO ‘MADE IN CHINA’ ISSUE 1, September 2013 From ‘Made in Greece’ to ‘Made in China’: a 21st Century Touring Revival of Golfo, a 19th Century Greek Melodrama Panayiota Konstantinakou PhD Candidate in Theatre Studies, Aristotle University ABSTRACT The article explores the innovative scenographic approach of HoROS Theatre Company of Thessaloniki, Greece, when revisiting an emblematic text of Greek culture, Golfo, the Shepherdess by Spiridon Peresiadis (1893). It focuses on the ideological implications of such a revival by comparing and contrasting the scenography of the main versions of this touring work in progress (2004-2009). Golfo, a late 19th century melodrama of folklore character, has reached over the years a wide and diverse audience of both theatre and cinema serving, at the same time, as a vehicle for addressing national issues. At the dawn of the 21st century, in an age of excessive mechanization and rapid globalization, HoROS Theatre Company, a group of young theatre practitioners, revisits Golfo by mobilizing theatre history and childhood memory and also by alluding to school theatre performances, the Japanese manga, computer games and the wider audiovisual culture, an approach that offers a different perspective to the national identity discussion. KEYWORDS HoROS Theatre Company Golfo dramatic idyll scenography manga national identity 104 FILMICON: Journal of Greek Film Studies ISSUE 1, September 2013 Time: late 19th century. Place: a mountain village of Peloponnese, Greece. Golfo, a young shepherdess, and Tasos, a young shepherd, are secretly in love but are too poor to support their union. Fortunately, an English lord, who visits the area, gives the boy a great sum of money for rescuing his life in an archaeological expedition and the couple is now able to get engaged. -

Transantiquity

TransAntiquity TransAntiquity explores transgender practices, in particular cross-dressing, and their literary and figurative representations in antiquity. It offers a ground-breaking study of cross-dressing, both the social practice and its conceptualization, and its interaction with normative prescriptions on gender and sexuality in the ancient Mediterranean world. Special attention is paid to the reactions of the societies of the time, the impact transgender practices had on individuals’ symbolic and social capital, as well as the reactions of institutionalized power and the juridical systems. The variety of subjects and approaches demonstrates just how complex and widespread “transgender dynamics” were in antiquity. Domitilla Campanile (PhD 1992) is Associate Professor of Roman History at the University of Pisa, Italy. Filippo Carlà-Uhink is Lecturer in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Exeter, UK. After studying in Turin and Udine, he worked as a lecturer at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and as Assistant Professor for Cultural History of Antiquity at the University of Mainz, Germany. Margherita Facella is Associate Professor of Greek History at the University of Pisa, Italy. She was Visiting Associate Professor at Northwestern University, USA, and a Research Fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation at the University of Münster, Germany. Routledge monographs in classical studies Menander in Contexts Athens Transformed, 404–262 BC Edited by Alan H. Sommerstein From popular sovereignty to the dominion -

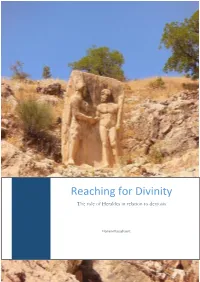

Reaching for Divinity the Role of Herakles in Relation to Dexiosis

Reaching for Divinity The role of Herakles in relation to dexiosis Florien Plasschaert Utrecht University RMA ANCIENT, MEDIEVAL, AND RENAISSANCE STUDIES thesis under the supervision of dr. R. Strootman | prof. L.V. Rutgers Cover Photo: Dexiosis relief of Antiochos I of Kommagene with Herakles at Arsameia on the Nymphaion. Photograph by Stefano Caneva, distributed under a CC-BY 2.0 license. 1 Reaching for Divinity The role of Herakles in relation to dexiosis Florien Plasschaert Utrecht 2017 2 Acknowledgements The completion of this master thesis would not have been possible were not it for the advice, input and support of several individuals. First of all, I owe a lot of gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Rolf Strootman, whose lectures not only inspired the subject for this thesis, but whose door was always open in case I needed advice or felt the need to discuss complex topics. With his incredible amount of knowledge on the Hellenistic Period provided me with valuable insights, yet always encouraged me to follow my own view on things. Over the course of this study, there were several people along the way who helped immensely by providing information, even if it was not yet published. Firstly, Prof. Dr. Miguel John Versluys, who was kind enough to send his forthcoming book on Nemrud Dagh, an important contribution to the information on Antiochos I of Kommagene. Secondly, Prof. Dr. Panagiotis Iossif who even managed to send several articles in the nick of time to help my thesis. Lastly, the National Numismatic Collection department of the Nederlandse Bank, to whom I own gratitude for sending several scans of Hellenistic coins. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

LAW and LAW COURTS in ANCIENT GREECE Rosalind Thomas The

LAW AND LAW COURTS IN ANCIENT GREECE Rosalind Thomas The Institute of Classical Studies and the wider University of London have been an important catalyst for work on Greek law and the Athenian law courts, and the Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies has been able to reflect this. We bring together here a rich collection of twelve articles by scholars who from various angles have examined the actual, practical operation of the law and the law courts through the techniques of Athenian oratory. The wealth of evidence for the operation of the law courts and the assembly from Athens means that most of these articles focus upon Athenian rhetoric and law in the heyday of its democracy. Theories about argument in oratory have a wider application across the Greek world, and two articles included here range beyond Athens in thinking about the nature and application of law. A series of seminars held at the Institute of Classical Studies, and the colloquia on the ‘New Hypereides’ discovered in the Archimedes Palimpsest and on ‘Profession and Performance’, created excellent opportunities to explore the interlocking questions and debates about the role of law, the rule of law, and the relation of legal procedures and rhetoric in democratic Athens. We cannot examine law by itself without the apparatus within which it was applied and the structures – either cultural or political – in which it was created, and then argued over, supported, evaded, and put into action. There is a continuing debate about how far the Athenian law courts really kept to the law; did they not get distracted by irrelevant arguments or emotive narrative, fine and clever speakers, fraught periods of high tension, and of course by the highly skilled techniques which the semi-professional orators increasingly exercised? As the techniques of Athenian oratory and persuasion developed in the late fifth century, so did the techniques of ‘proof’. -

The Arts and Crafts Movement: Exchanges Between Greece and Britain (1876-1930)

The Arts and Crafts Movement: exchanges between Greece and Britain (1876-1930) M.Phil thesis Mary Greensted University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Contents Introduction 1 1. The Arts and Crafts Movement: from Britain to continental 11 Europe 2. Arts and Crafts travels to Greece 27 3 Byzantine architecture and two British Arts and Crafts 45 architects in Greece 4. Byzantine influence in the architectural and design work 69 of Barnsley and Schultz 5. Collections of Greek embroideries in England and their 102 impact on the British Arts and Crafts Movement 6. Craft workshops in Greece, 1880-1930 125 Conclusion 146 Bibliography 153 Acknowledgements 162 The Arts and Crafts Movement: exchanges between Greece and Britain (1876-1930) Introduction As a museum curator I have been involved in research around the Arts and Crafts Movement for exhibitions and publications since 1976. I have become both aware of and interested in the links between the Movement and Greece and have relished the opportunity to research these in more depth. It has not been possible to undertake a complete survey of Arts and Crafts activity in Greece in this thesis due to both limitations of time and word constraints. -

Scout Uniform, Scout Sign, Salute and Handshake

In this Topic: Participation Promise and Law Scout Uniform, Scout Salute and Scout Handshake Scouts and Flags Scouting History Discussion with the Scout Leader Introducing Tenderfoot Level The Journey Life in the Troop is a journey. As in any journey one embarks on, there needs to be proper preparation for the adventure ahead. This is important so as to steer clear of obstacles and perils, which, with good foresight, can often be avoided. As Scouts we follow our simple motto: Be Prepared! With this in mind you can start your preparations for the journey ahead… The Tenderfoot This level offers a starting point for a new member in the troop. For those Cubs whose time has come to move up from the pack, the Tenderfoot level is a stepping stone linking the pack with the troop. For those scouts who have joined from outside the group, this will be the beginning of their scouting life. How do I achieve this level? The five sections in this level can be done in any order. If you are a Cub Scout moving up from the pack, you will have already started the Cub Scout link badge. The Tenderfoot level is started at the same time. As you can see some of the requirements are the same for both awards. If you have just joined the scouting movement as part of the troop, this level will provide you with all the basic information to help you learn what scouting is all about. Look at the sheet on the next page so that you are able to keep track of your progress. -

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed As the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed as the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon By Brian A. Sprague Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor Bau-Hwa Hsieh Western Oregon University Thursday, June 07, 2007 Readers Professor Benedict Lowe Professor Narasingha Sil Copyright © Brian A. Sprague 2007 The Parthenon frieze has been the subject of many debates and the interpretation of it leads to a number of problems: what was the subject of the frieze? What would the frieze have meant to the Athenian audience? The Parthenon scenes have been identified in many different ways: a representation of the Panathenaic festival, a mythical or historical event, or an assertion of Athenian ideology. This paper will examine the Parthenon Frieze in relation to the metopes, pediments, and statues in order to prove the validity of the suggestion that it depicts the Panathenaic festival just preceding the battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The main problems with this topic are that there are no primary sources that document what the Frieze was supposed to mean. The scenes are not specific to any one type of procession. The argument against a Panathenaic festival is that there are soldiers and chariots represented. Possibly that biggest problem with interpreting the Frieze is that part of it is missing and it could be that the piece that is missing ties everything together. The Parthenon may have been the only ancient Greek temple with an exterior sculpture that depicts any kind of religious ritual or service. Because the theme of the frieze is unique we can not turn towards other relief sculpture to help us understand it. -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury.