Urban Resilience, Climate Change and Adaptation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legendary Archipelago Excursions

EXCURSIONS LEGENDARY ARCHIPELAGO - 7 NIGHT 2021 Why book a Celestyal excursion Although we say it ourselves, the destinations on a Celestyal cruise are rather special. Call us biased but we think they are among the most exciting, beautiful, historic, iconic and evocative in the world. So a very warm welcome to our Legendary Archipelago excursions. Joining us on the seven night itinerary, you will be immersed in the most fabulous experiences living and breathing the myths and legends of Ancient Greece, discovering long past civilisations, following in the footsteps of great figures from history and seeing some of the most wondrous scenery on the planet. From classical Athens to beautiful Thessaloniki, Mykonos, Santorini, Rhodes, Limassol and scenic Agios Nikolaos. You will be amazed at what we can see and do in a week. We like to feel that we are taking you on your very own Greek Odyssey across the Aegean. And nobody knows the Eastern Mediterranean and the Greek Islands better than we do. You can be sure of that. Whether the history and culture is your thing or you are more about the outstanding natural beauty, the magnificent beaches or indeed the whole experience wrapped up together, we have something to match. Our specially designed excursions are central to your Celestyal experience with our expert guides taking you step by step through your voyage of discovery and really bringing our destinations alive. Sometimes in history it’s not easy to work out where facts end and legends begin. So please fire up your imagination and join us to find out. -

Department Town Address Postcode Telephone Etoloakarnania Agrinio

Department Town Address Postcode Telephone Etoloakarnania Agrinio 1, Eirinis square, Dimitrakaki street 301 00 2641046346 Etoloakarnania Mesologgi 45, Charilaou Trikoupi street 302 00 2631022487 Etoloakarnania Nafpaktos 1, Athinon street 303 00 2634038210 Etoloakarnania Amfilohia Vasileos Karapanou street 305 00 2642023302 Argolida Argos 12, Danaou street 212 00 2751069042 Argolida Nafplio 35, Argous street 211 00 2752096478 Argolida Porto Heli Porto Heli Argolidas 210 61 2754052102 Arkardia Megalopoli 15, Kolokotroni street 222 00 2791021131 Arkardia Tripoli 48, Ethinikis Antistaseos street 221 00 2710243770 Arta Arta 129, Skoufa street 471 00 2681077020 Attica Athens 316, Acharnon street & 26 Atlantos street 112 52 2102930333 Attica Agios Dimitrios 54, Agiou Dimitriou street 173 41 2109753953 Attica Agios Dimitrios 276, Vouliagmenis avenue 173 43 2109818908 Attica Agios Dimitrios 9 - 11, Agiou Dimitriou street 173 43 2109764322 Attica Agia Paraskevi 429, Mesogeion avenue 153 43 2106006242 Attica Athens - Piraeus 153, Piraeus Avenue 118 53 2104815333 Attica Athens - Aristeidou 1, Aristeidou street 105 59 2103227778 Attica Athens 79, Alexandras avenue 114 74 2106426650 Attica Athens - Plateia Viktorias 2, Victoria square 104 34 2108220800 Attica Athens - Stadiou 7, Stadiou street 105 62 2103316892 Attica Egaleo 266, Iera Odos street 122 42 2105316671 126, Vasilissis Sofias street & 2, Feidippidou Attica Abelokipoi street 115 27 2106461200 Attica Amfiali 32, Pavlou Fissa street 187 57 2104324300 Attica Palaio Faliro 82, Amfitheas avenue -

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The eighth-century revolution Version 1.0 December 2005 Ian Morris Stanford University Abstract: Through most of the 20th century classicists saw the 8th century BC as a period of major changes, which they characterized as “revolutionary,” but in the 1990s critics proposed more gradualist interpretations. In this paper I argue that while 30 years of fieldwork and new analyses inevitably require us to modify the framework established by Snodgrass in the 1970s (a profound social and economic depression in the Aegean c. 1100-800 BC; major population growth in the 8th century; social and cultural transformations that established the parameters of classical society), it nevertheless remains the most convincing interpretation of the evidence, and that the idea of an 8th-century revolution remains useful © Ian Morris. [email protected] 1 THE EIGHTH-CENTURY REVOLUTION Ian Morris Introduction In the eighth century BC the communities of central Aegean Greece (see figure 1) and their colonies overseas laid the foundations of the economic, social, and cultural framework that constrained and enabled Greek achievements for the next five hundred years. Rapid population growth promoted warfare, trade, and political centralization all around the Mediterranean. In most regions, the outcome was a concentration of power in the hands of kings, but Aegean Greeks created a new form of identity, the equal male citizen, living freely within a small polis. This vision of the good society was intensely contested throughout the late eighth century, but by the end of the archaic period it had defeated all rival models in the central Aegean, and was spreading through other Greek communities. -

Greece, 1821-1941. ~ Ebook Greece, 1821-1941

- < Greece, 1821-1941. ~ eBook Greece, 1821-1941. American Friends of Greece - The Short Description: - - Poland -- History -- 1980-1989 -- Sources. Poland -- History -- 1945-1980 -- Sources. Greece.Greece, 1821-1941. -Greece, 1821-1941. Notes: Title in Greek on cover. This edition was published in 1941 Filesize: 48.64 MB Tags: #Rochester #Genealogy #(in #Monroe #County, #New #York) Monroe County NY Church Records Athens, Athens School of Fine Arts, Nikiforos Lytras 1833-1933 retrospective exhibition, April 1933, no. The Short For more information on how to locate offline newspapers, see our article on. During the Greek War of Independence 1821—1827 from the Ottomans—which had a nationalistic and liberal character—and for the first decades after the liberation, a number of liberal French-educated politicians and scholars attempted unsuccessfully to introduce the Napoleonic Civil Code or some clone of it as the Greek Civil Code. Includes declassified records returned to file after February 2016 release by Hoover. Rochester Genealogy (in Monroe County, New York) USA: City of Los Angeles. PDF from the original on 29 November 2014. Monroe County NY Church Records Cemetery Transcriptions from NEHGS Billion Graves WorldCat Cemetery Transcriptions from NEHGS Cemetery Transcriptions from NEHGS WorldCat Cemetery Transcriptions from NEHGS Find a Grave US Gen Web Billion Graves Family History Library Family History Library Family History Library US Gen Web Billion Graves Interment US Gen Web WorldCat Find a Grave Billion Graves Interment Billion -

Name Address Postal City Mfi Id Head Office Res* Greece

MFI ID NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CITY HEAD OFFICE RES* GREECE Central Banks GR010 Bank of Greece, S.A. 21, Panepistimiou Str. 102 50 Athens No Total number of Central Banks : 1 Credit Institutions GR060 ABN Amro Bank 348, Syngrou Avenue 176 74 Athens NL ABN AMRO Bank N.V. Yes GR077 Achaiki Co-operative Bank, L.L.C. 66, Michalakopoulou Str. 262 21 Patra Yes GR056 Aegean Baltic Bank S.A. 28, Diligianni Str. 145 62 Athens Yes GR014 Alpha Bank, S.A. 40, Stadiou Str. 102 52 Athens Yes GR100 American Bank of Albania Greek Branch 14, E. Benaki Str. 106 78 Athens AL American Bank of Albania Yes GR080 American Express Bank 280, Kifissias Avenue 152 32 Athens US American Express Yes Company GR047 Aspis Bank S.A. 4, Othonos Str. 105 57 Athens Yes GR043 ATE Bank, S.A. 23, Panepistimiou Str. 105 64 Athens Yes GR016 Attica Bank, S.A. 23, Omirou Str. 106 72 Athens Yes GR081 Bank of America N.A. 35, Panepistimiou Str. 102 27 Athens US Bank of America Yes Corporation GR073 Bank of Cyprus Limited 170, Alexandras Avenue 115 21 Athens CY Bank of Cyprus Public Yes Company Ltd GR050 Bank Saderat Iran 25, Panepistimiou Str. 105 64 Athens IR Bank Saderat Iran Yes GR072 Bayerische Hypo und Vereinsbank A.G. 7, Irakleitou Str. 106 73 Athens DE Bayerische Hypo- und Yes Vereinsbank AG GR105 BMW Austria Bank GmbH Zeppou 33 166 57 Athens AT BMW Austria Bank GmbH Yes GR070 BNP Paribas 94, Vas. Sofias Avenue 115 28 Athens FR Bnp paribas Yes GR039 BNP Paribas Securities Services 94, Vas. -

Revolt and Crisis in Greece

REVOLT AND CRISIS IN GREECE BETWEEN A PRESENT YET TO PASS AND A FUTURE STILL TO COME How does a revolt come about and what does it leave behind? What impact does it have on those who participate in it and those who simply watch it? Is the Greek revolt of December 2008 confined to the shores of the Mediterranean, or are there lessons we can bring to bear on social action around the globe? Revolt and Crisis in Greece: Between a Present Yet to Pass and a Future Still to Come is a collective attempt to grapple with these questions. A collaboration between anarchist publishing collectives Occupied London and AK Press, this timely new volume traces Greece’s long moment of transition from the revolt of 2008 to the economic crisis that followed. In its twenty chapters, authors from around the world—including those on the ground in Greece—analyse how December became possible, exploring its legacies and the position of the social antagonist movement in face of the economic crisis and the arrival of the International Monetary Fund. In the essays collected here, over two dozen writers offer historical analysis of the factors that gave birth to December and the potentialities it has opened up in face of the capitalist crisis. Yet the book also highlights the dilemmas the antagonist movement has been faced with since: the book is an open question and a call to the global antagonist movement, and its allies around the world, to radically rethink and redefine our tactics in a rapidly changing landscape where crises and potentialities are engaged in a fierce battle with an uncertain outcome. -

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

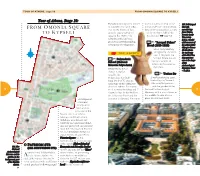

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

![Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements [Full Text, Not Including Figures] J.L](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6957/greek-color-theory-and-the-four-elements-full-text-not-including-figures-j-l-1306957.webp)

Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements [Full Text, Not Including Figures] J.L

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements Art July 2000 Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgc Benson, J.L., "Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgc/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Color Theory and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire ABOUT THIS BOOK Why does earlier Greek painting (Archaic/Classical) seem so clear and—deceptively— simple while the latest painting (Hellenistic/Graeco-Roman) is so much more complex but also familiar to us? Is there a single, coherent explanation that will cover this remarkable range? What can we recover from ancient documents and practices that can objectively be called “Greek color theory”? Present day historians of ancient art consistently conceive of color in terms of triads: red, yellow, blue or, less often, red, green, blue. This habitude derives ultimately from the color wheel invented by J.W. Goethe some two centuries ago. So familiar and useful is his system that it is only natural to judge the color orientation of the Greeks on its basis. To do so, however, assumes, consciously or not, that the color understanding of our age is the definitive paradigm for that subject. -

Conference Guide

Conference Guide Conference Venue Conference Location: Radisson Blu Athens Park Hotel 5* 5Hotel Athens” Radisson Blu Park Hotel Athens first opened its doors in 1976 on the border of the central park of Athens, Pedion Areos (Martian Field), in a safe part of the city. For 35 years the lovely park has been a wonderful host and marked the very identity of this leading deluxe hotel. Now, we thought, it is time for the hotel to host the park inside. This was the inspiration behind our recent renovation, which came to prove a virtual rebirth for Park Hotel Athens. Address: 10 Alexandras Ave. -10682 Athens-Greece Tel: +30 210 8894500 Fax: +30 210 8238420 URL: http://www.rbathenspark.com/index.php History of Athens According to tradition, Athens was governed until c.1000 B.C. by Ionian kings, who had gained suzerainty over all Attica. After the Ionian kings Athens was rigidly governed by its aristocrats through the archontate until Solon began to enact liberal reforms in 594 B.C. Solon abolished serfdom, modified the harsh laws attributed to Draco (who had governed Athens c.621 B.C.), and altered the economy and constitution to give power to all the propertied classes, thus establishing a limited democracy. His economic reforms were largely retained when Athens came under (560–511 B.C.) the rule of the tyrant Pisistratus and his sons Hippias and Hipparchus. During this period the city's economy boomed and its culture flourished. Building on the system of Solon, Cleisthenes then established a democracy for the freemen of Athens, and the city remained a democracy during most of the years of its greatness. -

ARCL 0066: the Emergence of Bronze Age Aegean States

UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ARCL 0066: The Emergence of Bronze Age Aegean States 2019-2020 - Term 2 Undergraduate Year 2-3 option, 15 credits Coursework deadlines: Monday 21st February 2020, Monday 3rd April 2020 (TBC) Co-ordinator: Dr. Borja Legarra Herrero [email protected], Room 106 1 1. OVERVIEW Short Description This course provides a survey of Aegean prehistory from The Neolithic until c. 1500-1400 BC. It focuses on the origins of complex societies during the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC and the dynamics of the Minoan palatial societies that followed. It provides a broadly chronologically overview of the region’s long-term transformations and the remarkably rich data (material, iconographic and archival) on which interpretations are based. It encourages a thematic treatment, within a theoretically informed, problem-oriented framework, of major processes including: state formation, elaboration and collapse; production, trade and consumption in and beyond the Aegean; archaeologies of cult and death; the interpretation of symbols and images; and the place of the prehistoric Aegean within the wider Mediterranean and Near Eastern world. The course equally emphasises the need to understand how interpretations and data collection strategies have developed, and the impact this has had on accounts of Aegean prehistory. Week-by-week summary (lectures are Monday, 10-12.00, in Room 410). Date Session Topic 13 Jan. 1 Introduction: Aegean space, time and environments. 2 Is ‘Minoan’ the right word? Biases in the study of the Aegean Bronze Age. 20 Jan. 3 Neolithics: taming of a fragmented landscape. 4 Seminar: Fieldwork in the Aegean: Archaeologists’ paradise? 27 Jan. -

Timeline of the Peloponnesian

CSTS119: CULTURE & CRISIS IN THE GOLDEN AGE OF ATHENS Timeline of Athens during the Peloponnesian War POLITICAL & MILITARY EVENTS CULTURAL EVENTS 432 Revolt of Potidaea. The ‘Megarian decree’ passed at Athens. Phidias completes the Parthenon frieze and the pediments Peloponnesian League declares for war. of the Parthenon; he dies soon after this date. Empedocles dies. Athens bans teaching of atheism. 431 First year of the Peloponnesian War.—The Archidamian Thucydides begins work on Histories. Euripides: Medea War (431-421). Theban attack on Plataea (March). First (3rd), <Philoctetes, Dictys> Peloponnesian invasion of Attica (May) under Spartan Archidamus. Athens wins Soilion and Cephallenia; takes Thronion and Atalanta: expels Aeginetans from Aegina. 430 Plague strikes Athens (430-427). Second invasion of Attica. Euripides: Heraclidae. Stesimbrotus writes critique of Expedition of Pericles to Argolis and failure at Epidaurus. Athenian power, On Themistocles, Thucydides, and Pericles deposed from strategia, tried, fined, and Pericles; he will also compose important works on reappointed strategos. Phormio operates in the west. Homeric allegory and Orphic practices. The important Sicilian historian Philistus of Syracuse born. 429 Capitulation of Potidaea; Pericles reinstated and dies, who Sophocles' Oedipus Rex and Trachiniae after this date (?). for more than, thirty years has guided the policy of Athens. First performance of a comedy by Eupolis. Lysias moves Peloponnesians besiege Plataea. Sea-victories of Phormio to Thurii after death of father Cephalus, whose house is in the Corinthian Gulf. the setting for Plato’s Republic 428 Third invasion of Attica. Revolt of Mytilene from Athens. Euripides: Hippolytus (1st). Plato and Xenophon born Introduction of war tax (eisphora). -

So, Here You Are in Athens

So, here you are in Athens! New city… new people… new places… a new way of living! Have no anxiety about this completely new way of living! Here is a simple guide to help you turn your residence in Athens into an unforgetable experience! Description of the Guide The following guide refers to clubs, bars, cafes, restaurants in Athens which are recommended because of their decoration, environment, prices or the different experiences they offer! Where it is possible, there is an estimation about the cost per person or a reference to the actual prices. Don’t worry…there are recommendations for every mood, budget or preference! Clubbing Guide Dance Stages : From progressive to techno BIOS BASEMENT _ Pireos Str. 8, Athens, tel. : 210 3425335 YES _ Mavrimichali & Gravias Str. 10, Pireaus, tel.: 6946 760798. Open only on Friday and Saturday. YOU (Playback by Pierro’’s) _ Dekeleon Str. 26, tel.: 210 3452220, 6947 745816 Massive Clubs BAROC’ E _ Stadiou square 5 & Agras Str., Kallimarmaro, tel.: 210 7565007 – 8. Freestyle and mainstream music. BIANCO NERO _ Vafeiochoriou Str. 65 (after Evelpidon), Polygono, tel.: 210 6465326 CAMEL CLUB _ Erakleidon Str. 74, Thiseio, tel.: 210 3476847, www.camelclub.gr DEXX CLUB _ Alexandras Avenue 87 & Drosi Str. 1 , Gyzi, tel. : 210 6465290 EGOIST _ Panepistimiou Str. 10, Athens, tel.: 210 3638201. Bottle of whisky €100, drink €10 HARD ROCK CAFÉ _ Fillelinon Str. 18, tel.: 210 3252742. Rock and mainstream music. American kitchen. The first shop of the famous brand in Athens. Open from 12 a.m. to very late every night.