The Music Association of Ireland Fostering a Voice for Irish Composers and Compositions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IRISH MUSIC AND HOME-RULE POLITICS, 1800-1922 By AARON C. KEEBAUGH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Aaron C. Keebaugh 2 ―I received a letter from the American Quarter Horse Association saying that I was the only member on their list who actually doesn‘t own a horse.‖—Jim Logg to Ernest the Sincere from Love Never Dies in Punxsutawney To James E. Schoenfelder 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A project such as this one could easily go on forever. That said, I wish to thank many people for their assistance and support during the four years it took to complete this dissertation. First, I thank the members of my committee—Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Paul Richards, Dr. Joyce Davis, and Dr. Jessica Harland-Jacobs—for their comments and pointers on the written draft of this work. I especially thank my committee chair, Dr. David Z. Kushner, for his guidance and friendship during my graduate studies at the University of Florida the past decade. I have learned much from the fine example he embodies as a scholar and teacher for his students in the musicology program. I also thank the University of Florida Center for European Studies and Office of Research, both of which provided funding for my travel to London to conduct research at the British Library. I owe gratitude to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for their assistance in locating some of the materials in the Victor Herbert Collection. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

NABMSA Reviews a Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association

NABMSA Reviews A Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association Vol. 5, No. 2 (Fall 2018) Ryan Ross, Editor In this issue: Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra, Ina Boyle (1889–1967): A Composer’s Life • Michael Allis, ed., Granville Bantock’s Letters to William Wallace and Ernest Newman, 1893–1921: ‘Our New Dawn of Modern Music’ • Stephen Connock, Toward the Rising Sun: Ralph Vaughan Williams Remembered • James Cook, Alexander Kolassa, and Adam Whittaker, eds., Recomposing the Past: Representations of Early Music on Stage and Screen • Martin V. Clarke, British Methodist Hymnody: Theology, Heritage, and Experience • David Charlton, ed., The Music of Simon Holt • Sam Kinchin-Smith, Benjamin Britten and Montagu Slater’s “Peter Grimes” • Luca Lévi Sala and Rohan Stewart-MacDonald, eds., Muzio Clementi and British Musical Culture • Christopher Redwood, William Hurlstone: Croydon’s Forgotten Genius Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra. Ina Boyle (1889-1967): A Composer’s Life. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2018. 192 pp. ISBN 9781782052647 (hardback). Ina Boyle inhabits a unique space in twentieth-century music in Ireland as the first resident Irishwoman to write a symphony. If her name conjures any recollection at all to scholars of British music, it is most likely in connection to Vaughan Williams, whom she studied with privately, or in relation to some of her friends and close acquaintances such as Elizabeth Maconchy, Grace Williams, and Anne Macnaghten. While the appearance of a biography may seem somewhat surprising at first glance, for those more aware of the growing interest in Boyle’s music in recent years, it was only a matter of time for her life and music to receive a more detailed and thorough examination. -

<Insert Image Cover>

An Chomhaırle Ealaíon An Tríochadú Turascáil Bhliantúil, maille le Cuntais don bhliain dar chríoch 31ú Nollaig 1981. Tíolacadh don Rialtas agus leagadh faoi bhráid gach Tí den Oireachtas de bhun Altanna 6 (3) agus 7 (1) den Acht Ealaíon 1951. Thirtieth Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 31st December 1981. Presented to the Government and laid before each House of the Oireachtas pursuant to Sections 6 (3) and 7 (1) of the Arts Act, 1951. Cover: Photograph by Thomas Grace from the Arts Council touring exhibition of Irish photography "Out of the Shadows". Members James White, Chairman Brendan Adams (until October) Kathleen Barrington Brian Boydell Máire de Paor Andrew Devane Bridget Doolan Dr. J. B. Kearney Hugh Maguire (until December) Louis Marcus (until December) Seán Ó Tuama (until January) Donald Potter Nóra Relihan Michael Scott Richard Stokes Dr. T. J. Walsh James Warwick Staff Director Colm Ó Briain Drama and Dance Officer Arthur Lappin Opera and Music Officer Marion Creely Traditional Music Officer Paddy Glackin Education and Community Arts Officer Adrian Munnelly Literature and Combined Arts Officer Laurence Cassidy Visual Arts Officer/Grants Medb Ruane Visual Arts Officer/Exhibitions Patrick Murphy Finance and Regional Development Officer David McConnell Administration, Research and Film Officer David Kavanagh Administrative Assistant Nuala O'Byrne Secretarial Assistants Veronica Barker Patricia Callaly Antoinette Dawson Sheilah Harris Kevin Healy Bernadette O'Leary Receptionist Kathryn Cahille 70 Merrion Square, Dublin 2. Tel: (01) 764685. An Chomhaırle Ealaíon An Chomhairle Ealaíon/The Arts Council is an independent organization set up under the Arts Acts 1951 and 1973 to promote the arts. -

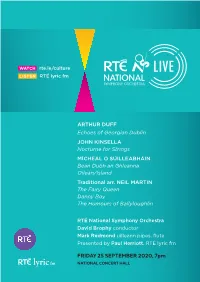

RTE NSO 25 Sept Prog.Qxp:Layout 1

WATCH rte.ie/culture LISTEN RTÉ lyric fm ARTHUR DUFF Echoes of Georgian Dublin JOHN KINSELLA Nocturne for Strings MÍCHEÁL Ó SÚILLEABHÁIN Bean Dubh an Ghleanna Oileán/Island Traditional arr. NEIL MARTIN The Fairy Queen Danny Boy The Humours of Ballyloughlin RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra David Brophy conductor Mark Redmond uilleann pipes, flute Presented by Paul Herriott, RTÉ lyric fm FRIDAY 25 SEPTEMBER 2020, 7pm NATIONAL CONCERT HALL 1 Arthur Duff 1899-1956 Echoes of Georgian Dublin i. In College Green ii. Song for Amanda iii. Minuet iv. Largo (The tender lover) v. Rigaudon Arthur Duff showed early promise as a musician. He was a chorister at Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral and studied at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, taking his degree in music at Trinity College, Dublin. He was later awarded a doctorate in music in 1942. Duff had initially intended to enter the Church of Ireland as a priest, but abandoned his studies in favour of a career in music, studying composition for a time with Hamilton Harty. He was organist and choirmaster at Christ Church, Bray, for a short time before becoming a bandmaster in the Army School of Music and conductor of the Army No. 2 band based in Cork. He left the army in 1931, at the same time that his short-lived marriage broke down, and became Music Director at the Abbey Theatre, writing music for plays such as W.B. Yeats’s The King of the Great Clock Tower and Resurrection, and Denis Johnston’s A Bride for the Unicorn. The Abbey connection also led to the composition of one of Duff’s characteristic works, the Drinking Horn Suite (1953 but drawing on music he had composed twenty years earlier as a ballet score). -

YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares Beside the Edmund Dulac Memorial Stone to W

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3-8, 10-11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN: YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE: YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares beside the Edmund Dulac memorial stone to W. B. Yeats. Roquebrune Cemetery, France, 1986. Private Collection. THE LIVING STREAM ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF A. NORMAN JEFFARES YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 A Special Issue Edited by Warwick Gould http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Gould, et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text. -

Austin Clarke Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 83 Austin Clarke Papers (MSS 38,651-38,708) (Accession no. 5615) Correspondence, drafts of poetry, plays and prose, broadcast scripts, notebooks, press cuttings and miscellanea related to Austin Clarke and Joseph Campbell Compiled by Dr Mary Shine Thompson 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 Abbreviations 7 The Papers 7 Austin Clarke 8 I Correspendence 11 I.i Letters to Clarke 12 I.i.1 Names beginning with “A” 12 I.i.1.A General 12 I.i.1.B Abbey Theatre 13 I.i.1.C AE (George Russell) 13 I.i.1.D Andrew Melrose, Publishers 13 I.i.1.E American Irish Foundation 13 I.i.1.F Arena (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.G Ariel (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.H Arts Council of Ireland 14 I.i.2 Names beginning with “B” 14 I.i.2.A General 14 I.i.2.B John Betjeman 15 I.i.2.C Gordon Bottomley 16 I.i.2.D British Broadcasting Corporation 17 I.i.2.E British Council 17 I.i.2.F Hubert and Peggy Butler 17 I.i.3 Names beginning with “C” 17 I.i.3.A General 17 I.i.3.B Cahill and Company 20 I.i.3.C Joseph Campbell 20 I.i.3.D David H. Charles, solicitor 20 I.i.3.E Richard Church 20 I.i.3.F Padraic Colum 21 I.i.3.G Maurice Craig 21 I.i.3.H Curtis Brown, publisher 21 I.i.4 Names beginning with “D” 21 I.i.4.A General 21 I.i.4.B Leslie Daiken 23 I.i.4.C Aodh De Blacam 24 I.i.4.D Decca Record Company 24 I.i.4.E Alan Denson 24 I.i.4.F Dolmen Press 24 I.i.5 Names beginning with “E” 25 I.i.6 Names beginning with “F” 26 I.i.6.A General 26 I.i.6.B Padraic Fallon 28 2 I.i.6.C Robert Farren 28 I.i.6.D Frank Hollings Rare Books 29 I.i.7 Names beginning with “G” 29 I.i.7.A General 29 I.i.7.B George Allen and Unwin 31 I.i.7.C Monk Gibbon 32 I.i.8 Names beginning with “H” 32 I.i.8.A General 32 I.i.8.B Seamus Heaney 35 I.i.8.C John Hewitt 35 I.i.8.D F.R. -

Passion and Intellect in the Music of Elizabeth Maconchy DBE (1907–1994)

Passion and Intellect in the Music of Elizabeth Maconchy DBE (1907–1994) Ailie Blunnie Thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Master of Literature in Music Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare July 2010 Head of Department: Professor Fiona Palmer Supervisor: Dr Martin O’Leary Contents Acknowledgements i List of Abbreviations iii List of Illustrations iv Preface ix Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Part 1: The Early Years (1907–1939): Life and Historical Context 8 Early Education 10 Royal College of Music 11 Octavia Scholarship and Promenade Concert 17 New Beginnings: Leaving College 19 Macnaghten–Lemare Concerts 22 Contracting Tuberculosis 26 Part 2: Music of the Early Years 31 National Trends 34 Maconchy’s Approach to Composition 36 Overview of Works of this Period 40 The Land: Introduction 44 The Land: Movement I: ‘Winter’ 48 The Land: Movement II: ‘Spring’ 52 The Land: Movement III: ‘Summer’ 55 The Land: Movement IV: ‘Autumn’ 57 The Land: Summary 59 The String Quartet in Context 61 Maconchy’s String Quartets of the Period 63 String Quartet No. 1: Introduction 69 String Quartet No. 1: Compositional Procedures 74 String Quartet No. 1: Summary 80 String Quartet No. 2: Introduction 81 String Quartet No. 2: Movement I 83 String Quartet No. 2: Movement II 88 String Quartet No. 2: Movement III 91 String Quartet No. 2: Movement IV 94 Part 2: Summary 97 Chapter 3 Part 1: The Middle Years (1940–1969): Life and Historical Context 100 World War II 101 After the War 104 Accomplishments of this Period 107 Creative Dissatisfaction 113 Part 2: Music of the Middle Years 115 National Trends 117 Overview of Works of this Period 117 The String Quartet in Context 121 Maconchy’s String Quartets of this Period 122 String Quartet No. -

PDF (Volume 2)

Durham E-Theses A.J. Potter (1918-1980): The career and creative achievement of an Irish composer in social and cultural context Zuk, Patrick How to cite: Zuk, Patrick (2007) A.J. Potter (1918-1980): The career and creative achievement of an Irish composer in social and cultural context, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2911/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Chapter4 Choral works with orchestra 4.1 Introduction n view of Potter's early training as a chorister, it is perhaps surprising to find that choral music comprises a comparatively small proportion of his output: I one might have expected him to follow up his early Missa Brevis with other substantial choral works of various kinds. The fact that he did not can undoubtedly be explained by the circumstances of Irish musical life at the period: in bleak contrast to Britain, not only were good choirs few and far between, but there was little evidence of interest in choral music throughout the country at large. -

Collections of Musicians' Letters in the UK and Ireland: a Scoping Study

Collections of musicians’ letters in the UK and Ireland: a scoping study Katharine Hogg, Rachel Milestone, Alexis Paterson, Rupert Ridgewell, Susi Woodhouse London December 2011 1 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all those who gave their time and expertise to make this scoping study possible. They include: the staff of organisations and individuals responding to the survey, staff at the BBC Written Archives, Oxford University Press, the London Symphony Orchestra, Cheltenham Festivals, Royal Festival Hall, Royal Academy of Music, Royal Society of Musicians, and those who kindly agreed to be interviewed on their use and perception of archives of letters. © Music Libraries Trust 2012 2 Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Rationale ........................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. The resource................................................................................................................................................ 5 2.2. Repositories ................................................................................................................................................ 5 2.3. Resource discovery...................................................................................................................................... 6 2.4. Data integration.......................................................................................................................................... -

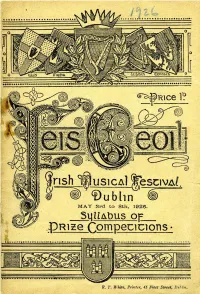

2Ltuabus °E . .J2rl~E Com'qec1cions·

[ Q MAY .3rd to 8th, 1928. 2ltUAbus °E_. _ .J2Rl~e COm'QeC1CIOnS· 8.. 7', White, Printer, 4S Fleet Street, Dul·/:"u. " ( Notice to Competitors. OMPETITORS are requested to be careful that in the Feil Ceoil C Competitions, both Instrumental and Vocal, the specified edition is procured. Arrangements have been made by Mesers. Pigott &. Co., Ltd., THI~TIETH "3 Grafton Street, Dublin, to supply Candidates with the Test Piec~s in the correct editions at the lowe.t possible rates. F EIS C EO I L IRISH MUSICAL FESTIVAL. DUBLIN. MAY 3rd to 8th. 1926. SYLLABUS OF PRIZE COMPETITION S AND REPQRT OF MUSIC EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE. AND ALL THINOS MUSICAL. PIANOS ORGANS PLAYER - PIANOS GRAMOPHONES RECORDS VIOLINS Oreatest Facilities for Selection In Ireland. Service. of Expert Tuner. covera entire Country. Repair. by highly Skilled Craftsmen in the Firm'. Up-to-date Factory. DUBLIN : PUBLISHED BY THE FEIS CEOIL AS SOCIATION. 37 MOLESWORTH ST. 1926. GRAFTON ST. a SUFFOLK ST., DUBLIN. L ADd at CORK .. LIMUIC•• R. T. J-f/'lIite, Printer, 45 Fleet Street, Dtlblin, CONTENTS. ................................................ PAGE. 13 Adjudicators, List of. (1926) 6 It is earne.stiy ~equested that Competitions, Con~ltlons of . NOTICE. Constitution of Fels Ceoll 5 all Competitors should use Committees ... ... ... .. 4 Donors to Prize Fund (1925) ... .., 11 the correct and specified editions as stated Members of Association, List of (1925-26) 41 43 in Syllabus. •• •• :: .• Prize Winners, Calendar of .. Railway Travelling Facilities ... .. 11 Above are obtainable at Messrs. Report of Committee and Balance Sheets for 1925 34-40 McCullough's, 56 Dawson Street, Dublin. TEST PIECES AND PRIZES. -

Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Masters Applied Arts 2018 Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930. David Scott Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appamas Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Scott, D. (2018) Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930.. Masters thesis, DIT, 2018. This Theses, Masters is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900–1930 David Scott, B.Mus. Thesis submitted for the award of M.Phil. to the Dublin Institute of Technology College of Arts and Tourism Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama February 2018 i ABSTRACT Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, arrangements of Irish airs were popularly performed in Victorian drawing rooms and concert venues in both London and Dublin, the most notable publications being Thomas Moore’s collections of Irish Melodies with harmonisations by John Stephenson. Performances of Irish ballads remained popular with English audiences but the publication of Stanford’s song collection An Irish Idyll in Six Miniatures in 1901 by Boosey and Hawkes in London marks a shift to a different type of Irish song.