200 Years of Irish Symphonies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IRISH MUSIC AND HOME-RULE POLITICS, 1800-1922 By AARON C. KEEBAUGH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Aaron C. Keebaugh 2 ―I received a letter from the American Quarter Horse Association saying that I was the only member on their list who actually doesn‘t own a horse.‖—Jim Logg to Ernest the Sincere from Love Never Dies in Punxsutawney To James E. Schoenfelder 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A project such as this one could easily go on forever. That said, I wish to thank many people for their assistance and support during the four years it took to complete this dissertation. First, I thank the members of my committee—Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Paul Richards, Dr. Joyce Davis, and Dr. Jessica Harland-Jacobs—for their comments and pointers on the written draft of this work. I especially thank my committee chair, Dr. David Z. Kushner, for his guidance and friendship during my graduate studies at the University of Florida the past decade. I have learned much from the fine example he embodies as a scholar and teacher for his students in the musicology program. I also thank the University of Florida Center for European Studies and Office of Research, both of which provided funding for my travel to London to conduct research at the British Library. I owe gratitude to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for their assistance in locating some of the materials in the Victor Herbert Collection. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

<Insert Image Cover>

An Chomhaırle Ealaíon An Tríochadú Turascáil Bhliantúil, maille le Cuntais don bhliain dar chríoch 31ú Nollaig 1981. Tíolacadh don Rialtas agus leagadh faoi bhráid gach Tí den Oireachtas de bhun Altanna 6 (3) agus 7 (1) den Acht Ealaíon 1951. Thirtieth Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 31st December 1981. Presented to the Government and laid before each House of the Oireachtas pursuant to Sections 6 (3) and 7 (1) of the Arts Act, 1951. Cover: Photograph by Thomas Grace from the Arts Council touring exhibition of Irish photography "Out of the Shadows". Members James White, Chairman Brendan Adams (until October) Kathleen Barrington Brian Boydell Máire de Paor Andrew Devane Bridget Doolan Dr. J. B. Kearney Hugh Maguire (until December) Louis Marcus (until December) Seán Ó Tuama (until January) Donald Potter Nóra Relihan Michael Scott Richard Stokes Dr. T. J. Walsh James Warwick Staff Director Colm Ó Briain Drama and Dance Officer Arthur Lappin Opera and Music Officer Marion Creely Traditional Music Officer Paddy Glackin Education and Community Arts Officer Adrian Munnelly Literature and Combined Arts Officer Laurence Cassidy Visual Arts Officer/Grants Medb Ruane Visual Arts Officer/Exhibitions Patrick Murphy Finance and Regional Development Officer David McConnell Administration, Research and Film Officer David Kavanagh Administrative Assistant Nuala O'Byrne Secretarial Assistants Veronica Barker Patricia Callaly Antoinette Dawson Sheilah Harris Kevin Healy Bernadette O'Leary Receptionist Kathryn Cahille 70 Merrion Square, Dublin 2. Tel: (01) 764685. An Chomhaırle Ealaíon An Chomhairle Ealaíon/The Arts Council is an independent organization set up under the Arts Acts 1951 and 1973 to promote the arts. -

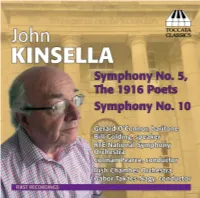

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

11 May 2008 Waterford Institute Of

Society for Musicology in Ireland Annual Conference 9 – 11 May 2008 Waterford Institute of Technology (College Street Campus) Waterford Institute of Technology welcomes you to the Sixth Annual Conference of the Society for Musicology in Ireland. We are particularly delighted to welcome our distinguished keynote speaker, Professor John Tyrrell from Cardiff University. Programme Committee Dr. Hazel Farrell Dr. David J. Rhodes (Chair) Conference Organisation Fionnuala Brennan Paddy Butler Jennifer Doyle Dr. Hazel Farrell Marc Jones Dr. Una Kealy Dr. David J. Rhodes Technician: Eoghan Kinane Acknowledgements Dr. Gareth Cox Dr. Rachel Finnegan, Head of the Department of Creative and Performing Arts, WIT Norah Fogarty Dr. Michael Murphy Professor Jan Smaczny Waterford Crystal WIT Catering Services Exhibition Four Courts Press will be exhibiting a selection of new and recent books covering many areas from ancient to twenty-first century music, opera, analysis, ethnomusicology, popular and film music on Saturday 10 May Timetable Humanities & Art Building: Room HA06 Room HA07 Room HA08 Room HA17 (Auditorium) Main Building (Ground floor): Staff Room Chapel Friday 9 May 1.00 – 2.00 Registration (Foyer of Humanities & Art Building) 2.00 – 3.30 Sessions 1 – 3 Session 1 (Room HA06): Nineteenth-century Reception and Criticism Chair: Lorraine Byrne Bodley (National University of Ireland Maynooth) • Adèle Commins (Dundalk Institute of Technology): Perceptions of an Irish composer: reception theories of Charles Villiers Stanford • Aisling Kenny (National -

Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Masters Applied Arts 2018 Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930. David Scott Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appamas Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Scott, D. (2018) Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930.. Masters thesis, DIT, 2018. This Theses, Masters is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900–1930 David Scott, B.Mus. Thesis submitted for the award of M.Phil. to the Dublin Institute of Technology College of Arts and Tourism Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama February 2018 i ABSTRACT Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, arrangements of Irish airs were popularly performed in Victorian drawing rooms and concert venues in both London and Dublin, the most notable publications being Thomas Moore’s collections of Irish Melodies with harmonisations by John Stephenson. Performances of Irish ballads remained popular with English audiences but the publication of Stanford’s song collection An Irish Idyll in Six Miniatures in 1901 by Boosey and Hawkes in London marks a shift to a different type of Irish song. -

Music Supplement

1964 L books [ Tailoring Under the supervision of most We. books our London-trained cutter silver I I:S. C. TRI N ITY N EWS | GOWNS, HOODS, ,aheny. books CASSOCKS, BLAZERS livered I )Oste~ A Dublin University Undergraduate Weekly 3 CHURCH LANE 01. HOD6ES FIG61S COLLEGE GREEN bretta,. IIRYSON ... where else ? THURSDAY, 3rd DECEMBER, 1963 PRICE THREEPENCE match. LTD. :heese COMMONS AT CROSSROADS? S.R.C. Committee Reports The S.R.C. Sub-Committee which was recently set up to investigate Commons has completed its report. It expanded its terms of reference to include all aspects of evening catering, and its inquiry proceeded along the three lines of examining relevant documents, interviewing various bodies of College opinion, and assessing undergraduate feelings; Under the first head it was made voluntary and argued that seen that the Board had appointed three aims should be sought. a committee under Professor These are, in order of priority, Moody which suggested the pro- the saving of the historic vision of an evening meal for non- Commons as a common, orderly resident students. This was and graced meal for staff and accepted by the Board which students, the provision of a asked the Agent and Treasurer to wholesome meal at the lowest examine its practical application. possible price, and the saving of From their investigations the the " Cista Communis" from all following facts emerged: unnecessary expense. Commons is expensive because From the results of the of the use of waiters, the pro- questionnaire held by the S.R.C. ns vision of stout and the variations to assess undergraduate opinion ,, in attendance. -

Calendar 2006-07 Z5 GENERAL INDEX A

GENERAL INDEX A OTHER UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES V1 RE-ADMISSION F10 A.G. LEVENTIS LECTURER B17 SPECIFIC COURSE REQUIREMENTS F3 ABBEY PRIZE S2 STUDENTS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS F11 ABBOTT CLINICAL NUTRITION PRIZE S38 TRINITY ACCESS PROGRAMMES F11 ABD EL-MOTAAL PRIZES S53 ADMISSIONS OFFICE STAFF B119 ABRIDGEMENT OF COURSE ADRIAN PHILLIPS FUND S63 See under general regulations for each ADRIAN STOKES FELLOWSHIP S45 Faculty ADVANCED MATERIALS, PHYSICS AND ABSENCE FROM EXAMINATIONS H6 CHEMISTRY OF ACADEMIC AFFAIRS STAFF B118 MODERATORSHIP COURSE O7, O25 ACADEMIC AND SENIOR ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF PRIZE S50 PROMOTIONS COMMITTEE B141 ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON HONORARY DEGREES ACADEMIC APPEALS COMMITTEE B141, H10 B134 ACADEMIC PRACTICE ADVISORY COMMITTEE AEGROTAT DEGREE H8 B142 AIB PROFESSOR OF CHILDHOOD RESEARCH B81 ACADEMIC PROGRESS H3, H11 ALAN BOXBERGER MEDAL S34 ACADEMIC SECRETARY B118 ALEXANDER PRIZE S35 ACADEMIC YEAR AND TERMS A1, H3 ALICE MC AVOY PRIZE S57 ACADEMICALS E10 ALICE OLDHAM MEMORIAL PRIZE S61 ACCESS PROGRAMMES, TRINITY F11 ALL HALLOWS D1 PRIZES S60 ALLEN PRIZE S46 STAFF B119 ALMANACK A1 ACCESS STEERING COMMITTEE B146 ALUMNI, RECORDER OF B111 ACCESS TO SCRIPTS H9 AMERICAN HISTORY PRIZE S26 ACCOMMODATION see RESIDENCE AMY ALLEN AND HENRIETTE MICKS PRIZE S46 ACCOMMODATION AND CATERING SERVICES, ANATOMY STAFF B35 DIRECTOR OF, AND STAFF B123 ANCIENT HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY ACCOUNTANCY PRIZES S53 PRIZES S22, S23, S24 ACTING STUDIES TWO-SUBJECT MODERATORSHIP COURSE K9 PROFESSIONAL DEGREE L7 ANDERSON EXHIBITION AND PRIZE S2, S3 STAFF B14 ANDREW -

The Use of Newspapers As a Source for Musicological Research: a Case

The Use of Newspapers as a Source for Musicological Research: A Case Study of Dublin Musical Life 1840–44 Catherine Ferris Thesis submitted to National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare April 2011 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisor: Professor Barra Boydell Contents Acknowledgements i Abbreviations ii List of Tables iii Part I Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Methodology 11 Thesis Overview 14 Editorial Decisions 16 The Class Context 17 Chapter 2: The Use of Newspapers for Musicological Research 19 Newspaper Characteristics 24 Newspaper Access and Formats 26 Considerations in the Use of Newspapers for Musicological Research 28 Newspaper Bias 29 The Audience: Literacy, Circulation and Reading Rooms 32 History of the Press 37 Freeman’s Journal 40 Evening Packet 49 Saunders’s News-Letter 58 Comparative Bias 65 Single Newspaper Study 71 Chapter 3: Case Study: Dublin Music Societies, 1840–1844 74 Hibernian Catch Club 75 Anacreontic Society 90 Philharmonic Society 110 Antient Concerts Society 130 University Choral Society 151 University Church Music Society 172 Societa Armonica 176 Dublin Sacred Harmonic Society 179 Dublin Harmonic Society 182 Metropolitan Choral Society 184 Amateur Harmonic Society 198 Tradesmen’s Harmonic Society 201 Dublin Concordant Society 205 Orpheus Society 207 Case Study Conclusion 211 Chapter 4: Conclusion 215 Part II Register of Musical Data on the Music Societies in the Freeman’s Journal, the Evening Packet and the Saunders’s News-Letter, 1840–1844 222 Bibliography 463 Abstract 505 Acknowledgements Foremost, I am indebted to my supervisor Professor Barra Boydell for his inestimable guidance, support and encouragement throughout my studies. -

The Irish Composers Project: Primary Sources for Research and Promotion of Irish Art Music

THE IRISH COMPOSERS PROJECT: PRIMARY SOURCES FOR RESEARCH AND PROMOTION OF IRISH ART MUSIC PATRICIA FLYNN Introduction Irish contemporary art music is an often-overlooked aspect of the musical traditions of Ireland. In 1995 composer Raymond Deane (1953-) coined the term 'the honor of non-existence' to describe the condition of contemporary composers in Ireland.(1) it is telling still that in considerations Of Irish culture, such as in the interdisciplinary field of Irish studies, the emphasis has to a large extent been on one of our three main music traditions.(2) The term Irish Music for many signifies traditional music, the fold music of the people. Sometimes it is used to refer to our popular tradition, particularly rock music, but rarely will it bring to mind the current art music tradition. Perhaps this is as it should be; there will always be a smaller and specialized interest in classical music. However, that this is one of our traditions should not be forgotten. An understanding of this tradition informs an understanding of ourselves and the place of music in the Irish imaginative exploration of ideas. The role of music- ology illuminating these ideas and developing wider under- standing and knowledge of this music is clear; as is the role of music institutions in making this music generally known and promoting access to this part of our cultural heritage. This essay outlines a project in which both academic and cultural institutions worked in partnership to create a digital archive of Irish contemporary art music, ensuring thus primary sources for future music research, performance and wider promotion. -

Musical Memories

~ ---- APPENDIX 1 MUSICAL MEMORIES Heneghan, Frank O'Grady, Dr Geraldine Andrews, Edward O'Reilly, Dr James]. Beckett, Dr Walter Keogh, Val O'Rourke, Miceal Bonnie,Joe King, Superintendent John Calthorpe, Nancy Larchet, Dr John F Roche, Kevin Darley, Arthur Warren Maguire, Leo Ronayne, john Davin, Maud McCann, Alderman John Rowsome, Leo Donnelly, Madame Lucy McNamara. Michael Sauerzweig, Colonel F C. Dunne, Dr Veronica Mooney, Brighid Sherlock, Dr Lorean G. Gannon, Sister Mary O'Brien, Joseph Valentine, Hubert O'Callaghan, Colonel Frederick Gillen, Professor Gerard Walton, Martin A. Greig, William Sydney O'Conor, Dr John 85 86 Edward Andrews were all part-time, and so could get holiday pay by getting the dole. Many summer days I spent in a Edward Andrews was porter, and his wife, queue at the Labour Exchange. Mary Andrews, was housekeeper, in the The large room at the head of the main stairs Assembly House, South William Street, from was the Library, just three or four cases of books about 1885. He was the first porter connected and music, looked after by Willie Reidy, who also with the Municipal School of Music. They were taught the cello in this room. The Principal at this employed by Dublin Corporation, and remained time was Joseph O'Brien. in South William Street when the Municipal Soon a terrible thought struck me. The way I School of Music moved premises. They had a was living meant that I should go through this life daughter, Mary, who was one of the first piano without ever playing in a string quartet. This was students, and her two daughters, Eithne Russell intolerable, so before long I left a free half-hour in and the late Maura Russell, were both students my timetable and went to Willie Reidy to learn the and teachers in the College of Music. -

Benjamin Britten's Compositions for Children and Amateurs: Cloaking

i O ^ 3 3 1 Benjamin Britten’s compositions for children and amateurs: cloaking simplicity behind the veil of sophistication by Angie Flynn Thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth as part- fulfilment for the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Head of Department: Professor Gerard Gillen Department of Music National University of Ireland Maynooth Co. Kildare Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Department of Music National University of Ireland Maynooth Co. Kildare Naas, July 2006 \ 7 h N o r w i c h E a s t S u f f o l k s o u t h w o l d ; PEASENHA1X N o /\ t h YOXFORD SAXMUNDHAM GREAT flLC N H A M AL JOE BURGH PART OP j THE To I p n v ith & L o n d o n SUFFOLK COAST Contents Preface ii Acknowledgements v Introduction vii Benjamin Britten’s compositions for children and amateurs: cloaking simplicity behind the veil of sophistication Chapter 1 - 1 Chapter 2- 16 Chapter 3 - 30 Chapter 4 - 44 Conclusion 57 Appendix A 60 Appendix B 62 Appendix C 71 Appendix D 75 Bibliography 76 Abstract 80 Preface This thesis conforms to the house style of the Department of Music, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. As far as possible an adherence to The Oxford Dictionary of English has been made for spellings, where a choice is necessary. Any direct quotations from Britten’s letters or diaries (or, indeed, any correspondence relating to him) maintain his rather idiosyncratic and variable spelling style (e.g. ‘abit’) and his practice for underlining words, which would appear to be a habit he retained from childhood, and no attempt has thus been made to alter them.