Remembrances of the Irish Past Through the Prism of the Present in Music by Donnacha Dennehy (B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Euro Report Gimme Shelter Session Pixies FREE

Issue #4 Summer 2012 Published Quarterly. FREE. Or if you really like us you can always log onto www.rabble.ie to donate. Ah g’wan... INSIDE. Disco Liberation rabble takes a time machine to a rather unusual parish hop... Betaville Is it a playground for the city’s hipper twenty somethings? Club Photography Are DSLR swinging douchebags wrecking our club nights? THE Single Parents OBSTACLES How cutbacks are making FACING it real tough out there.. FESTIVAL PROMOTERS A Euro Report Gimme Shelter Session Pixies A Bohemian boyo tells us how it A gay asylum seeker shares his Meet our new peddlers of holistic went down in Poznan... experience... lifestyle advice .... “The intern will gain practical Work Experience. experience performing physical activities such as balancing, walking, lifting and handling of 2 materials.” - I shit you not. Kildare, chinese restaurant. JobBridge.ie {THE RANT} Rick Astley and rain in Mosney. We’ve come a long way since homosexuality Blah was illegal and a gay nightclub was better in than out, as it were. Check out the interview with Tonie Walsh about the infamous Flikkers club on Fownes Blah St in ’79. Anarchaeologist takes a look at DCC’s Beta project and is relieved that the local authority seems to be learning from past mistakes. THE ALL-NIGHT While our new Mob Rules section EDITORIAL SESSION, demonstrates the power of modern FUELLED BY COFFEE communication is a far cry from the AND NICOTINE WITH xerox world of yesteryear. The rabble project is only as strong as those who CRACKLING VINYL IN THE get involved and with our growing BACKGROUND COULD online presence you’ve no excuse! Our BE FROM ANYTIME IN recent Boomtown competition shows {EYE} THE LAST 50 YEARS. -

(Some Other) Notes on Conceptualisms Jennifer Walshe I

(Some Other) Notes on Conceptualisms Jennifer Walshe I was asked to write about my relationship to conceptualism (including new conceptualism). I will start by talking about how conceptualism functions in my own work. A wide range of the work I do might be described as conceptual. My latest project is Historical Documents of the Irish Avant‐Garde. For this project, I worked in collaboration with a wide number of people to create a fictional history of Irish avant‐garde music, stretching from the mid‐1830s to the 1980s. All the materials related to this project are housed at aisteach.org, the website of the Aisteach Foundation, a fictional organisation which is positioned as “the avant‐garde archive of Ireland.” The site contains hours of music, numerous articles, scores, documents and historical ephemera. Every detail of this project was composed, written and designed with the utmost care and attention to detail. It’s a serious exercise in speculative composition, fiction and world‐building. The roots of the Historical Documents project lie in Dordán, a work I began in 2009. I was living in New York and playing with Tony Conrad a lot. We had been discussing the argument around who is considered the inventor of minimalism and Dordán was made in response to that. In Dordán I position the inventor of minimalism as a traditional Irish musician called Pádraig Mac Giolla Mhuire. The work includes recordings which purport to be of Mac Giolla Mhuire and collaborators playing the trad‐inflected drone music which they called “dordán” in Cork in 1952. The work also includes forged Ellis Island immigration records, explanatory text and other visual materials. -

Defeat of Tariff Measure in States Virtually Assured Electors

WHERE TO GO TO-NIGHT Columbia—Big Happiness. Variety—A House Divided. WEATHER FORECAST Princess—Sylvia Runs Away. Royal—Harriet and the Bluer. Dominion—The Charm School. Pantages—Vaudeville. For 36 hours ending 6 p.m. Friday: Romano—The Restless Sex. Victoria and vicinity—Southerly winds, unsettled and mild, with rain. rna SIXTEEN PAGES VICTORIA, B. C., THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 3, 1921 VOL. 58. NO. 28 ARRESTED FOR STEALING PREMIER OF QUEENSLAND FORMER PREMIER OF Electors Exercise RUSSIAN SABLE COAT SEES ASIATIC MENACE POLAND TO STATES; Defeat of Tariff Toronto, Feb. 3.—^Tilliam Cowan, Brisbane* Queensland, Feb. 3. Pre IGNACE PADEREWSKI of Montreal, is under arrest in Mon mier E. G? Theodore declared to-day treal on a charge of stealing a Royal that anyone who doubted that Aus Franchise To-day in Russian sable coat valued at $3,500 tralians would soon be called upon to from a wagon at the Toronto store Measure in States of the Holt Renfrew Company on defend their homes against Asiatic Lorries Blown Up by Mine; September 30 last. The coat, which I invasion, was living in a fool’s para was recovered in Montreal, had been dise. Asiatic ideals and aspirations, Bombs Hurled he added, were a menace to the Ideals Delta Constituency through the Boxer Rebellion in [ of the Australian Labor Party. Virtually Assured Four Killed in Ambush at China. Ballinalee Straight Contest Between Alex. D. Paterson and Frank Dublin, Feb. 3.—Four men are Railway Company Plans Senate Fails to Adopt Closure to Get Vote on Fordney dead as a result of an ambush of a Mackenzie Expected to Draw Large Vote; Polling squad of auxiliary police at Bal Bill; Will Not Be Seriously Pressed For Passage, liqalee near here yesterday, two of Returns From Remote Stations Will Be Late. -

Classical Guitar Music by Irish Composers: Performing Editions and Critical Commentary

L , - 0 * 3 7 * 7 w NUI MAYNOOTH OII» c d I »■ f£ir*«nn WA Huad Classical Guitar Music by Irish Composers: Performing Editions and Critical Commentary John J. Feeley Thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth as fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music (Performance) 3 Volumes Volume 1: Text Department of Music NUI Maynooth Head of Department: Professor Gerard Gillen Supervisor: Dr. Barra Boydell May 2007 VOLUME 1 CONTENTS ABSTRACT i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 13 APPROACHES TO GUITAR COMPOSITION BY IRISH COMPOSERS Historical overview of the guitar repertoire 13 Approaches to guitar composition by Irish composers ! 6 CHAPTER 2 31 DETAILED DISCUSSION OF SEVEN SELECTED WORKS Brent Parker, Concertino No. I for Guitar, Strings and Percussion 31 Editorial Commentary 43 Jane O'Leary, Duo for Alto Flute and Guitar 52 Editorial Commentary 69 Jerome de Bromhead, Gemini 70 Editorial Commentary 77 John Buckley, Guitar Sonata No. 2 80 Editorial Commentary 97 Mary Kelly, Shard 98 Editorial Commentary 104 CONTENTS CONT’D John McLachlan, Four pieces for Guitar 107 Editorial Commentary 121 David Fennessy, ...sting like a bee 123 Editorial Commentary 134 CHAPTER 3 135 CONCERTOS Brent Parker Concertino No. 2 for Guitar and Strings 135 Editorial Commentary 142 Jerome de Bromhead, Concerto for Guitar and Strings 148 Editorial Commentary 152 Eric Sweeney, Concerto for Guitar and Strings 154 Editorial Commentary 161 CHAPTER 4 164 DUOS Seoirse Bodley Zeiten des Jahres for soprano and guitar 164 Editorial -

Ireland: in Search of Reform for Public Service Media Funding

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ulster University's Research Portal Ireland: In search of reform for public service media funding Phil Ramsey, Ulster University [email protected] http://ulster.academia.edu/PhilRamsey | http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5873-489X Published as: Ramsey, P. (2018) Ireland: In search of reform for public service media funding. In C. Herzog, H. Hilker, L. Novy and Torun, O. (Eds), Transparency and Funding of Public Service Media: deutsche Debatte im internationalen Kontex (pp.77–90). Wiesbaden: Springer VS. Abstract This chapter discusses public service media (PSM) in Ireland in the context of the recent financial crisis and major demographic changes. It considers some of the factors impacting domestic PSM that are similar to those in other mature media systems in Europe, such as declining funding streams and debates over PSM-funding reform. After introducing the Irish social and political-economic context and providing for a brief historical review of PSM in Ireland, the roles of the domestic PSM organizations RTÉ and TG4 in the Irish media market are discussed. The chapter addresses initial government support for the introduction of a German-style household media fee, a Public Service Broadcasting Charge. While the charge was intended for introduction in 2015, it was later ruled out by the Irish Government in 2016. Ireland: in search of reform for public service media funding Public Service Media (PSM) has a long-tradition in the Republic of Ireland (ROI, hereafter Ireland), dating back to the commencement of the state radio service 2RN in January 1926.1 The state’s involvement in broadcasting later gave way to the main public broadcaster RTÉ, which has broadcast simultaneously on television and radio since New Year’s Eve 1961, and latterly, delivered public service content online. -

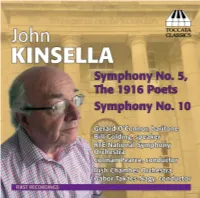

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

Submission of Men's Voices Ireland to Commission on the Future of Media

Submission of Men’s Voices Ireland to Commission on the Future of Media Journalism in crisis in the West We shall confine our remarks on media to social and political issues, in particular those social issues which we have been engaged with in our work. Trends in the Irish media have broadly followed those in other Western countries but particularly in the Anglosphere. The media has become a major player in at least shaping news rather than in reporting news as exemplified in the dissemination of partisan views along with the censorship of opposing views and this is happening in many western countries. Certain issues have become defining: a particular ideology obsessed with victimhood and so-called victim classes; issues of race, gender, sexual orientation or “woke” in the jargon; hate speech is another touchstone. Two key issues in the past 10 years which exemplify the media’s attitude have been the Brexit referendum in the UK and the US Presidential election of 2016. It is fair to say that both results came as a huge shock to the media which staunchly campaigned for a Remain vote in the UK and for a Clinton victory in the US. In neither case did the media carry out a dispassionate, impartial analysis of the trends, the swings which were at work in both cases. It ignored trends which pointed to a possible upset. It was as if the media wished to be a player in the result. Other headlines have been set in the US. In August 2019 the New York Times initiated the 1619 project, a series of essays which claimed that the founding act of the United States was not the Declaration of Independence of 1776 but rather the landing of a slave ship in Virginia in 1619. -

Scéim Teanga Do RTÉ 2019-2022 Faoi Alt 15 D'acht Na Dteangacha

Scéim Teanga do RTÉ 2019-2022 Faoi Alt 15 d’Acht na dTeangacha Oifigiúla 2003 Language Scheme for RTÉ 2019-2022 Under Section 15 of the Official Languages Act 2003 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Introduction from RTÉ Director-General ............................................................................................... 3 Chapter One: Preparation of the RTÉ Language Scheme ................................................................. 4 Commencement date ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter Two: Overview of Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ) ............................................................... 6 RTÉ’s Vision: ............................................................................................................................................. 7 RTÉ’s Mission is to: ................................................................................................................................ 7 RTÉ’s Values:............................................................................................................................................. 7 RTÉ’s organisational structure ................................................................................................................... 7 The Board of RTÉ .................................................................................................................................... 8 The RTÉ Executive ................................................................................................................................. -

The Tyranny of the Past?

The Tyranny of the Past? Revolution, Retrospection and Remembrance in the work of Irish writer, Eilis Dillon Volumes I & II Anne Marie Herron PhD in Humanities (English) 2011 St Patrick’s College, Drumcondra (DCU) Supervisors: Celia Keenan, Dr Mary Shine Thompson and Dr Julie Anne Stevens I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD in Humanities (English) is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: (\- . Anne Marie Herron ID No.: 58262954 Date: 4th October 2011 Thesis Abstract This thesis examines the extent to which Eilis Dillon's (1920-94) reliance on memory and her propensity to represent the past was, for her, a valuable motivating power and/or an inherited repressive influence in terms of her choices of genres, subject matter and style. Volume I of this dissertation consists of a comprehensive survey and critical analysis of Dillon's writing. It addresses the thesis question over six chapters, each of which relates to a specific aspect of the writer's background and work. In doing so, the study includes the full range of genres that Dillon employed - stories and novels in both Irish and English for children of various age-groups, teenage adventure stories, as well as crime fiction, literary and historical novels, short stories, poetry, autobiography and works of translation for an adult readership. The dissertation draws extensively on largely untapped archival material, including lecture notes, draft documents and critical reviews of Dillon's work. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

11 May 2008 Waterford Institute Of

Society for Musicology in Ireland Annual Conference 9 – 11 May 2008 Waterford Institute of Technology (College Street Campus) Waterford Institute of Technology welcomes you to the Sixth Annual Conference of the Society for Musicology in Ireland. We are particularly delighted to welcome our distinguished keynote speaker, Professor John Tyrrell from Cardiff University. Programme Committee Dr. Hazel Farrell Dr. David J. Rhodes (Chair) Conference Organisation Fionnuala Brennan Paddy Butler Jennifer Doyle Dr. Hazel Farrell Marc Jones Dr. Una Kealy Dr. David J. Rhodes Technician: Eoghan Kinane Acknowledgements Dr. Gareth Cox Dr. Rachel Finnegan, Head of the Department of Creative and Performing Arts, WIT Norah Fogarty Dr. Michael Murphy Professor Jan Smaczny Waterford Crystal WIT Catering Services Exhibition Four Courts Press will be exhibiting a selection of new and recent books covering many areas from ancient to twenty-first century music, opera, analysis, ethnomusicology, popular and film music on Saturday 10 May Timetable Humanities & Art Building: Room HA06 Room HA07 Room HA08 Room HA17 (Auditorium) Main Building (Ground floor): Staff Room Chapel Friday 9 May 1.00 – 2.00 Registration (Foyer of Humanities & Art Building) 2.00 – 3.30 Sessions 1 – 3 Session 1 (Room HA06): Nineteenth-century Reception and Criticism Chair: Lorraine Byrne Bodley (National University of Ireland Maynooth) • Adèle Commins (Dundalk Institute of Technology): Perceptions of an Irish composer: reception theories of Charles Villiers Stanford • Aisling Kenny (National -

The Capuchin Annual and the Irish Capuchin Publications Office

1 Irish Capuchin Archives Descriptive List Papers of The Capuchin Annual and the Irish Capuchin Publications Office Collection Code: IE/CA/CP A collection of records relating to The Capuchin Annual (1930-77) and The Father Mathew Record later Eirigh (1908-73) published by the Irish Capuchin Publications Office Compiled by Dr. Brian Kirby, MA, PhD. Provincial Archivist July 2019 No portion of this descriptive list may be reproduced without the written consent of the Provincial Archivist, Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, Ireland, Capuchin Friary, Church Street, Dublin 7. 2 Table of Contents Identity Statement.......................................................................................................................................... 5 Context................................................................................................................................................................ 5 History ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Archival History ................................................................................................................................. 8 Content and Structure ................................................................................................................................... 8 Scope and content ............................................................................................................................. 8 System of arrangement ....................................................................................................................