The Process of Preparing Irish Cello Sonatas (1968-1996) For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musica Ad Asiago

MUSICA AD ASIAGO ASIAGOFESTIVAL è organizzato dalla Associazione Culturale “Amici della Musica di Asiago” - “Fiorella Benetti Brazzale”, in collaborazione con la Parrocchia di S. Matteo, con il contributo e la collaborazione della Città di Asiago e l’Assessorato Turismo e Cultura. Si ringraziano in modo particolare la Brazzale, Burro delle Alpi - Alpilatte e Gran Moravia per il sostegno concesso, determinante per l'allestimento della stagione, nonché le altre ditte private che, aiutando la manifestazione, dimostrano sensibilità verso le attività che arricchiscono il soggiorno dei nostri ospiti e le esperienze culturali sull'altopiano. Un significativo ringraziamento anche a tutti coloro che in queste 53 edizioni hanno contribuito a rendere così intenso il Festival e un ricordo speciale alla sua fondatrice Fiorella Benetti Brazzale, senza la quale tutto ciò non sarebbe stato e non sarebbe tuttora possibile. Figure musicanti tratte dal “Gabinetto armonico pieno di strumenti sonori del Padre Filippo Bonanni al Santo Re David - In Roma MDCCXXII” riedito nella stamperia di Vincenzo Bona - In Torino MCMLXIX. ASIAGOFESTIVAL 2019 53^ EDIZIONE Martedì 6 Agosto - ore 21.00 Mercoledì 14 Agosto - ore 21.00 ASIAGO – Duomo di San Matteo ASIAGO – Teatro Millepini "Messe de requiem" “Omaggio al compositore ospite musiche di: Gabriel Fauré Artur Zagajewski” Coro città di Thiene "L'ottetto di violoncelli" Coro Giovanile di Thiene Cellopassionato Ensemble Laboratorio Corale Classico musiche di autori vari Ensemble dell'Officina Armonica soprano: Eleonora Donà baritono: Alberto Spadarotto direttore: Luigi Ceola Giovedì 15 Agosto ore 11.00 ASIAGO – Sala Consiliare del Municipio Giovedì 8 Agosto - ore 21.00 Incontro con il compositore ospite ASIAGO – Teatro Millepini Artur Zagajewski Strumentisti del Teatro Alla Scala Intervengono Julius Berger, Roberto Brazzale, Claudio Pasceri "Il sestetto d'archi" e Marco Pedrazzi musiche di: B. -

Joseph Kuipers Is One of the Rare Musical Voices of Today: the Fresh Sincerity of His Playing, Combined with Technical Sovereignty Over the Instrument

“Joseph Kuipers is one of the rare musical voices of today: the fresh sincerity of his playing, combined with technical sovereignty over the instrument. He draws a dark, singing sound out of his Ceruti Cello, and creates lines that seem to float effortlessly.” Berliner Abend Post American cellist Joseph Kuipers is renowned for his creativity and versatility in his captivating performances on both modern and gut strings. Appearing at festivals and music centers around the globe, he has performed at the Ravinia Music Festival, Aspen Music Festival, Les Festival International du Domaine Forget, Kronberg Academy, Ascoli Piceno Festival, Carl Orff Festival, and the World Cello Congress. Equally at home with modern and baroque performance styles, and often juxtaposing them in concert programs, Joseph has worked extensively with living composers, among them Robert Cogan, Heinz Holliger, Helmut Lachenmann and Arvo Part: and has performed with the Ensemble für Neue Musik Basel, Neue Musik Ensemble Mannheim, Second Instrumental Unit, New York, and the Callithumpian Consort of Boston. Joseph is the Artistic Director of the Fredericksburg Music Festival where world renowned European classical musicians gather in historic Fredericksburg TX for a week of music making. In 2010 Joseph founded the Marinus Project an international collective of chamber musicians dedicated to the tradition of classical music in our time. Marinus is the “Ensemble in Residence” at Washington and Lee University and Eastern University. In April 2011 the Marinus Ensemble received a $200,000 unrestricted artist development grant to further the Marinus Project. Joseph completed his undergraduate studies at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, where his primary teachers were Paul Katz for cello and Pozzi Escot for composition. -

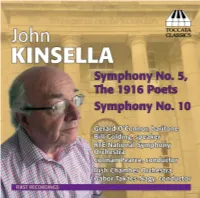

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

11 May 2008 Waterford Institute Of

Society for Musicology in Ireland Annual Conference 9 – 11 May 2008 Waterford Institute of Technology (College Street Campus) Waterford Institute of Technology welcomes you to the Sixth Annual Conference of the Society for Musicology in Ireland. We are particularly delighted to welcome our distinguished keynote speaker, Professor John Tyrrell from Cardiff University. Programme Committee Dr. Hazel Farrell Dr. David J. Rhodes (Chair) Conference Organisation Fionnuala Brennan Paddy Butler Jennifer Doyle Dr. Hazel Farrell Marc Jones Dr. Una Kealy Dr. David J. Rhodes Technician: Eoghan Kinane Acknowledgements Dr. Gareth Cox Dr. Rachel Finnegan, Head of the Department of Creative and Performing Arts, WIT Norah Fogarty Dr. Michael Murphy Professor Jan Smaczny Waterford Crystal WIT Catering Services Exhibition Four Courts Press will be exhibiting a selection of new and recent books covering many areas from ancient to twenty-first century music, opera, analysis, ethnomusicology, popular and film music on Saturday 10 May Timetable Humanities & Art Building: Room HA06 Room HA07 Room HA08 Room HA17 (Auditorium) Main Building (Ground floor): Staff Room Chapel Friday 9 May 1.00 – 2.00 Registration (Foyer of Humanities & Art Building) 2.00 – 3.30 Sessions 1 – 3 Session 1 (Room HA06): Nineteenth-century Reception and Criticism Chair: Lorraine Byrne Bodley (National University of Ireland Maynooth) • Adèle Commins (Dundalk Institute of Technology): Perceptions of an Irish composer: reception theories of Charles Villiers Stanford • Aisling Kenny (National -

Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Masters Applied Arts 2018 Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930. David Scott Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appamas Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Scott, D. (2018) Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930.. Masters thesis, DIT, 2018. This Theses, Masters is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900–1930 David Scott, B.Mus. Thesis submitted for the award of M.Phil. to the Dublin Institute of Technology College of Arts and Tourism Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama February 2018 i ABSTRACT Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, arrangements of Irish airs were popularly performed in Victorian drawing rooms and concert venues in both London and Dublin, the most notable publications being Thomas Moore’s collections of Irish Melodies with harmonisations by John Stephenson. Performances of Irish ballads remained popular with English audiences but the publication of Stanford’s song collection An Irish Idyll in Six Miniatures in 1901 by Boosey and Hawkes in London marks a shift to a different type of Irish song. -

200 Years of Irish Symphonies

Symphonies and Accompaniments: 200 Years of Irish Symphonies Paper read at the symposium ‘The Symphony and Ireland’, Dublin, DIT Conservatory of Music and Drama, 20 April 2013 © April 2013, Axel Klein, Ph.D., Frankfurt, Germany, www.axelklein.de Ireland’s musical traditions appear to offer little space for the symphonic genre. Beyond Charles Stanford, few international scholars would be able to name an Irish composer writing symphonies. Yet (as always), a closer look reveals that there is more than meets the eye. In this contribution my intention is to collect the empirical facts about symphony writing in Ireland and by Irish composers elsewhere. In doing so I will try to answer questions such as ‘How many Irish symphonies were there?’, ‘Who wrote them?’, ‘Could they be heard in Ireland?’ and ‘What was the heyday of Irish symphonies about?’. The answers will provide clues to further problems such as ‘What were the difficulties?’ and ‘Why don’t we know them?’. Thus I seek not only to give an overview of the symphonies in question, but also to the ‘accompaniments’ in cultural history that prevented or promoted the development of the genre in Ireland. To begin, let me draw your attention to the probably earliest use of the term ‘symphony’ in Ireland. It is included in the title of my presentation and of course I am alluding to the famous Irish Melodies collection of arrangements of Irish traditional songs by John Andrew Steven- son to poetry by Thomas Moore published in ten volumes and a supplement from 1808. When I began to study Irish musical history more than 25 years ago, Stevenson’s use of the term ‘symphony’ struck me as very odd. -

Calendar 2006-07 Z5 GENERAL INDEX A

GENERAL INDEX A OTHER UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES V1 RE-ADMISSION F10 A.G. LEVENTIS LECTURER B17 SPECIFIC COURSE REQUIREMENTS F3 ABBEY PRIZE S2 STUDENTS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS F11 ABBOTT CLINICAL NUTRITION PRIZE S38 TRINITY ACCESS PROGRAMMES F11 ABD EL-MOTAAL PRIZES S53 ADMISSIONS OFFICE STAFF B119 ABRIDGEMENT OF COURSE ADRIAN PHILLIPS FUND S63 See under general regulations for each ADRIAN STOKES FELLOWSHIP S45 Faculty ADVANCED MATERIALS, PHYSICS AND ABSENCE FROM EXAMINATIONS H6 CHEMISTRY OF ACADEMIC AFFAIRS STAFF B118 MODERATORSHIP COURSE O7, O25 ACADEMIC AND SENIOR ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF PRIZE S50 PROMOTIONS COMMITTEE B141 ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON HONORARY DEGREES ACADEMIC APPEALS COMMITTEE B141, H10 B134 ACADEMIC PRACTICE ADVISORY COMMITTEE AEGROTAT DEGREE H8 B142 AIB PROFESSOR OF CHILDHOOD RESEARCH B81 ACADEMIC PROGRESS H3, H11 ALAN BOXBERGER MEDAL S34 ACADEMIC SECRETARY B118 ALEXANDER PRIZE S35 ACADEMIC YEAR AND TERMS A1, H3 ALICE MC AVOY PRIZE S57 ACADEMICALS E10 ALICE OLDHAM MEMORIAL PRIZE S61 ACCESS PROGRAMMES, TRINITY F11 ALL HALLOWS D1 PRIZES S60 ALLEN PRIZE S46 STAFF B119 ALMANACK A1 ACCESS STEERING COMMITTEE B146 ALUMNI, RECORDER OF B111 ACCESS TO SCRIPTS H9 AMERICAN HISTORY PRIZE S26 ACCOMMODATION see RESIDENCE AMY ALLEN AND HENRIETTE MICKS PRIZE S46 ACCOMMODATION AND CATERING SERVICES, ANATOMY STAFF B35 DIRECTOR OF, AND STAFF B123 ANCIENT HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY ACCOUNTANCY PRIZES S53 PRIZES S22, S23, S24 ACTING STUDIES TWO-SUBJECT MODERATORSHIP COURSE K9 PROFESSIONAL DEGREE L7 ANDERSON EXHIBITION AND PRIZE S2, S3 STAFF B14 ANDREW -

Violin/Piano) - P

Polish Chamber Musicians‘ Association’s artistic offer 2019/ O 2020 Editor: Grzegorz Mania Catalogue number: SPMK 10b Skarbona – Zielona Gora – Krakow 2019 Polish Chamber Musicians’ Association (official name: Stowarzyszenie Polskich Muzyków Kameralistów) Address: Skarbona 4, 66-614 Skarbona KRS: 0000517330, REGON: 081227309 NIP: 9261671867 www.spmk.com.pl Office in Krakow: ul. Kwartowa 8/2 lok. A 31-419 Krakow phone number: +48 575 02 01 03 e-mail: [email protected] Management: phone number: +48 604 897 171 e-mail: [email protected] 1 Chamber ensembles under Polish Chamber Musicians‘ Association‘s management: Large chamber ensembles: Extra Sounds Ensemble – chamber orchestra - p. 3 Staśkiewicz/Sławek/Budnik/Rozmysłowicz/Kwiatkowski/Zdunik string sextet - p. 5 Lato/Cal/Lipień/Suruło/Lipień wind quintet - p. 13 Messages Quartet - p. 19 ETNOS Ensemble - p. 24 Trios: Herbert Piano Trio - p. 26 Francuz/Konarzewska/Kwiatkowski piano trio - p. 32 Staśkiewicz/Budnik/Zdunik string trio - p. 38 LLLeggiero Woodwind Trio - p. 42 Duos: Duo Molendowska/Samojło (soprano/piano) - p. 46 Duo Schmidt/Wezner (mezzosoprano/piano) - p. 50 Duo Hipp/Mania (mezzosoprano/piano) - p. 55 Duo Sławek/Różański (violin/piano) - p. 59 Duo Klimaszewska/Grynyuk (violin/piano) - p. 63 Duo Szczepaniak/Limonov (violin/piano) - p. 66 Duo Budnik/Mania (viola/piano) - p. 69 Duo Jaroszewska/Samojło (cello/piano) - p. 72 Ravel Piano Duo - p. 76 Zarębski Piano Duo - p. 78 LOSA Duo (percussion/piano) - p. 82 Duo Sławek/Zdunik (violin/cello) - p. 86 2 Chamber orchestra Extra Sounds Ensemble Extra Sounds Ensemble ESE brings together extraordinary young talents from Poland, England and Australia. It was formed in early 2010 by its leader and artistic director Alicja Śmietana. -

Musical Memories

~ ---- APPENDIX 1 MUSICAL MEMORIES Heneghan, Frank O'Grady, Dr Geraldine Andrews, Edward O'Reilly, Dr James]. Beckett, Dr Walter Keogh, Val O'Rourke, Miceal Bonnie,Joe King, Superintendent John Calthorpe, Nancy Larchet, Dr John F Roche, Kevin Darley, Arthur Warren Maguire, Leo Ronayne, john Davin, Maud McCann, Alderman John Rowsome, Leo Donnelly, Madame Lucy McNamara. Michael Sauerzweig, Colonel F C. Dunne, Dr Veronica Mooney, Brighid Sherlock, Dr Lorean G. Gannon, Sister Mary O'Brien, Joseph Valentine, Hubert O'Callaghan, Colonel Frederick Gillen, Professor Gerard Walton, Martin A. Greig, William Sydney O'Conor, Dr John 85 86 Edward Andrews were all part-time, and so could get holiday pay by getting the dole. Many summer days I spent in a Edward Andrews was porter, and his wife, queue at the Labour Exchange. Mary Andrews, was housekeeper, in the The large room at the head of the main stairs Assembly House, South William Street, from was the Library, just three or four cases of books about 1885. He was the first porter connected and music, looked after by Willie Reidy, who also with the Municipal School of Music. They were taught the cello in this room. The Principal at this employed by Dublin Corporation, and remained time was Joseph O'Brien. in South William Street when the Municipal Soon a terrible thought struck me. The way I School of Music moved premises. They had a was living meant that I should go through this life daughter, Mary, who was one of the first piano without ever playing in a string quartet. This was students, and her two daughters, Eithne Russell intolerable, so before long I left a free half-hour in and the late Maura Russell, were both students my timetable and went to Willie Reidy to learn the and teachers in the College of Music. -

Benjamin Britten's Compositions for Children and Amateurs: Cloaking

i O ^ 3 3 1 Benjamin Britten’s compositions for children and amateurs: cloaking simplicity behind the veil of sophistication by Angie Flynn Thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth as part- fulfilment for the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Head of Department: Professor Gerard Gillen Department of Music National University of Ireland Maynooth Co. Kildare Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Department of Music National University of Ireland Maynooth Co. Kildare Naas, July 2006 \ 7 h N o r w i c h E a s t S u f f o l k s o u t h w o l d ; PEASENHA1X N o /\ t h YOXFORD SAXMUNDHAM GREAT flLC N H A M AL JOE BURGH PART OP j THE To I p n v ith & L o n d o n SUFFOLK COAST Contents Preface ii Acknowledgements v Introduction vii Benjamin Britten’s compositions for children and amateurs: cloaking simplicity behind the veil of sophistication Chapter 1 - 1 Chapter 2- 16 Chapter 3 - 30 Chapter 4 - 44 Conclusion 57 Appendix A 60 Appendix B 62 Appendix C 71 Appendix D 75 Bibliography 76 Abstract 80 Preface This thesis conforms to the house style of the Department of Music, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. As far as possible an adherence to The Oxford Dictionary of English has been made for spellings, where a choice is necessary. Any direct quotations from Britten’s letters or diaries (or, indeed, any correspondence relating to him) maintain his rather idiosyncratic and variable spelling style (e.g. ‘abit’) and his practice for underlining words, which would appear to be a habit he retained from childhood, and no attempt has thus been made to alter them. -

The Irish Times Critic Described His Recital with the Dublin-Based Mezzo Soprano Bernadette Greevy As “A Synergic Relationship”

https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/piano-keys-strings-and-vocal-cords-books-about-irish-music-1.3974247 Piano keys, strings and vocal cords: books about Irish music Overlooked musicians, organists, choirmasters, dancers and harpists Paul Clements The energetic Ulster History Circle, which recognises the lives of well-known but frequently overlooked personalities, has recently unveiled blue plaques to two leading lights in Irish music whose lives are also recalled in a book. Music in Northern Ireland: Two Major Figures – Havelock Nelson and Joan Trimble (Grosvenor House Publishing, £12) by Alasdair Jamieson considers the overlapping but contrasting trajectories of the careers of both musicians. Nelson worked in Belfast for many years, while Trimble, whose family ran the Impartial Reporter newspaper in Enniskillen, was a celebrated performer. Absorbed in music, both enjoyed high profiles and touched the lives of many people. Occasionally their paths crossed and they were aware of each other at prize-winning feisanna; at the same ceremony in 1985 they were made fellows of the Royal Irish Academy of Music. Although born in Cork in 1917, Nelson moved with his family one month later to Sandycove, Co Dublin, where he began piano lessons at the age of five. In 1947, he took up a post with the BBC in Belfast, working initially on Children’s Hour. He spent time on country ceilidh outside broadcasts and The McCooeys, a radio saga of working-class life, before moving on to television programmes. A pianist, composer, conductor and operatic animateur, Nelson produced an extensive catalogue of compositions, and the book includes excerpts from his scores.