Note to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opinnäytteen Nimi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI Nobody's sidekick The Female Hero in Rick Riordan's The Heroes of Olympus Iina Haikka Master's Thesis English Philology Department of Modern Languages University of Helsinki April 2016 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Nykykielten laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Iina Haikka Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Nobody's sidekick: The female hero in Rick Riordan's The Heroes of Olympus Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Englantilainen filologia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu year 04/2016 56 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Pro gradu -tutkielmassani pohdin naishahmojen sankaruutta Rick Riordanin nuortenkirjasarjassa The Heroes of Olympus (2010-2014). Keskityn analyysissäni Riordanin naishahmoista kahteen, Piper McLeaniin ja Annabeth Chaseen, ja pyrin osoittamaan, että Riordan käyttää kummankin tytön kehityskaarta positiivisena esimerkkinä naisten sankaruudesta ja voimaantumisesta. Käytän tutkimusmenetelmänäni lähilukua ja aineistonani koko viisiosaista kirjasarjaa, erityisesti Piperin ja Annabethin näkökulmasta kirjoitettuja lukuja. Tutkielmani teoriaosassa tutustun sankaruuteen eri näkökulmista ja tarkastelen esimerkiksi terminologiaa ja sankareiden tunnusmerkkejä. Teoriakatsauksessani esitän, että tapa kuvata sankaruutta usein maskuliinisuuden -

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Salvate Il Soldato Paperino

Ovvero: Come la Disney aiutò gli Alleati nella battaglia contro il Nazifascismo INIZIAMO CON UN PICCOLO QUIZ • QUANDO INIZIA LA SECONDA GUERRA MONDIALE? Il primo settembre 1939, con l’invasione della Polonia … • QUALI SONO GLI SCHIERAMENTI IN CAMPO? Inglesi e Francesi vs Germania e dal ’40 Italia • QUANDO GLI USA ENTRANO IN GUERRA? L’8 dicembre 1941, un giorno dopo Pearl Harbor • QUANDO IL CANADA ENTRA IN GUERRA? Il 10 settembre 1939, poco dopo la Gran Bretagna • QUANDO FINISCE LA GUERRA? Nel maggio 1945 per l’Europa, in agosto 1945 per il Giappone • Venne fondata nel 1923 dai fratelli Walt e Roy Oliver Disney nel garage dello zio. • Nel 1928 appare per la prima volta il personaggio più celebre, Topolino. • Nel 1937 viene prodotto il primo lungometraggio, Biancaneve e i sette nani. Arriviamo quindi ora all’argomento di oggi… • Nel ‘40 la Disney si trovava in difficoltà economica, dovuta al poco successo di Pinocchio e Fantasia. • La guerra in Europa aveva chiuso anche quella fonte di reddito. • Nonostante lo scopo principale della Disney fosse l’intrattenimento, Walt inizia a intravedere le opportunità aperte dalla guerra in altri campi. I primi passi • Nel novembre del ‘40 Disney inizia a proporre i servizi dello studio alle agenzie della difesa. • Nel ’41 il Congresso approva il Lend-Lease Act che permette l’esportazione verso i paesi in guerra. • Disney crea una Defense Films Division con esperti nel settore americano, tra cui ingegneri della Lockheed. • Il 3 aprile ‘41 a Burbank mostra cinque cortometraggi, il più importante è Four Methods of Flush Riveting sull’uso dei Rivetti, a rappresentanti delle aziende private e agenzie governative. -

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 40 Sydney Program Guide Sun Feb 21, 2016 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G The Cham Cham Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS' WB SUNDAY WS PG Kids’ WB is celebrating its 11th fantastic year with bigger and better prizes than ever before! Join Lauren Phillips and Shane Crawford for lots of laughs, all your favourite cartoons, and the chance to win the best prizes in the land. 07:05 LOONEY TUNES CLASSICS Repeat G Prince Varmint/Captain Hareblower/The Slick Chick Adventures of iconic Looney Tunes characters Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Tweety, Silvester, Granny, the Tasmanian Devil, Speedy Gonzales, Marvin the Martian Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner. 07:30 SKINNER BOYS Captioned Repeat WS C The Tibetan Map Of Destiny In a small monastery in the mountains of Tibet, Obsidian Stone tricks the Skinner kids and steals Tara’s amulet. 08:00 SCOOBY-DOO! MYSTERY INCORPORATED Repeat WS PG Web of the Dreamweaver As the gang sets out to solve the mystery of the Dreamweaver, who is causing citizens to destroy the things they love the most, Fred gets a visit from his real parents. 08:30 THE AMAZING WORLD OF GUMBALL Repeat WS G The Laziest / The Ghost Gumball and Darwin challenge their father to a laziness competition, with the loser having to do the winner's chores. When a ghost named Carrie possesses Gumball's body in order to eat, he must learn to say "no" to her. -

Thinking About Journalism with Superman 132

Thinking about Journalism with Superman 132 Thinking about Journalism with Superman Matthew C. Ehrlich Professor Department of Journalism University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL [email protected] Superman is an icon of American popular culture—variously described as being “better known than the president of the United States [and] more familiar to school children than Abraham Lincoln,” a “triumphant mixture of marketing and imagination, familiar all around the world and re-created for generation after generation,” an “ideal, a hope and a dream, the fantasy of millions,” and a symbol of “our universal longing for perfection, for wisdom and power used in service of the human race.”1 As such, the character offers “clues to hopes and tensions within the current American consciousness,” including the “tensions between our mythic values and the requirements of a democratic society.”2 This paper uses Superman as a way of thinking about journalism, following the tradition of cultural and critical studies that uses media artifacts as tools “to size up the shape, character, and direction of society itself.”3 Superman’s alter ego Clark Kent is of course a reporter for a daily newspaper (and at times for TV news as well), and many of his closest friends and colleagues are also journalists. However, although many scholars have analyzed the Superman mythology, not so many have systematically analyzed what it might say about the real-world press. The paper draws upon Superman’s multiple incarnations over the years in comics, radio, movies, and television in the context of past research and criticism regarding the popular culture phenomenon. -

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 41 Sydney Program Guide Sun Mar 4, 2018 06:00 POKEMON Repeat WS G A Legendary Photo Op! When our heroes arrive at the foot of Mt. Molteau, the sudden appearance of a fiery Charmeleon lets them know that Trevor, their friend from Pokémon summer camp, is nearby! Cons.Advice: Supernatural Themes, Animated Violence 06:30 POKEMON Repeat WS G The Tiny Caretaker! Team Rocket has gotten their hands on a little Tyrunt, with plans to get it to evolve into a powerful Tyrantrum. Cons.Advice: Supernatural Themes, Animated Violence 07:00 KIDS' WB SUNDAY WS PG Kids' WB is celebrating its 13th fantastic year with bigger and better prizes than ever! Join Lauren Phillips and Shane Crawford for lots of laughs, special guests, wacky challenges and all your favourite cartoons. 07:05 LOONEY TUNES CLASSICS WS PG Adventures of iconic Looney Tunes characters Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Tweety, Silvester, Granny, the Tasmanian Devil, Speedy Gonzales, Marvin the Martian, Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner. 07:30 THE DAY MY BUTT WENT PSYCHO Captioned Repeat WS C All's Smell That Ends Smell / Cheer Window Can Zack and Deuce find the legendary Ned Smelly in time to save Mabeltown? Eleanor's new neighbour has a secret — and Zack and Deuce are going to uncover it at all costs! 08:00 THE AMAZING WORLD OF GUMBALL Repeat WS PG The Friend/The Saint Gumball and Darwin help Anais make up an imaginary friend -- who then turns out to be all too real./Gumball tries to make Alan lose his temper. -

Nationalism, the History of Animation Movies, and World War II Propaganda in the United States of America

University of Akureyri Faculty of Humanities and Social Science Modern Studies 2011 Intersections of Modernity: Nationalism, The History of Animation Movies, and World War II propaganda in the United States of America Kristján Birnir Ívansson Final BA Thesis in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Akureyri Faculty of Humanities and Social Science Modern studies 2011 Intersections of Modernity: Nationalism, The History of Animation Movies, and World War II propaganda in the United States of America Kristján Birnir Ívansson A final BA Thesis for 180 ECTS unit in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Instructor: Dr. Giorgio Baruchello Statements I hereby declare that I am the only author of this project and that is the result of own research Ég lýsi hér með yfir að ég einn er höfundur þessa verkefnis og að það er ágóði eigin rannsókna ______________________________ Kristján Birnir Ívansson It is hereby confirmed that this thesis fulfil, according to my judgement, requirements for a BA -degree in the Faculty of Hummanities and Social Science Það staðfestist hér með að lokaverkefni þetta fullnægir að mínum dómi kröfum til BA prófs í Hug- og félagsvísindadeild. __________________________ Giorgio Baruchello Abstract Today, animations are generally considered to be a rather innocuous form of entertainment for children. However, this has not always been the case. For example, during World War II, animations were also produced as instruments for political propaganda as well as educational material for adult audiences. In this thesis, the history of the production of animations in the United States of America will be reviewed, especially as the years of World War II are concerned. -

Propaganda Portraits and the Easing of American Anxieties Through WRA Films Krystle Stricklin

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Propaganda Portraits and the Easing of American Anxieties Through WRA Films Krystle Stricklin Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE, AND DANCE PROPAGANDA PORTRAITS AND THE EASING OF AMERICAN ANXIETIES THROUGH WRA FILMS By KRYSTLE STRICKLIN A Thesis submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2014 Krystle Stricklin defended this thesis on March 27, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Karen Bearor Professor Directing Thesis Adam Jolles Committee Member Laura Lee Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv Abstract ............................................................................................................................................v INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER ONE – SOCIAL DOCUMENTARIES ......................................................................16 -

Introduction: Frictive Pictures 1 Cartoon Internationale

Notes Introduction: Frictive Pictures 1. There may be even earlier social groups united by an interest in pre-cinematic visual technologies or animation-like performances such as shadow-plays. But before animation came into being as a cinematic genre between 1898 and 1906 (Crafton 1993, 6–9, 21), these groups could not be properly termed “anima- tion fan communities,” and should be called something else, such as “zoetrope hobbyists” or “utsushi-e [Japanese magic lantern] audiences.” For that reason, I have chosen to begin with film animation in the early twentieth century, starting specifically in 1906–7 with the earliest verifiable hand-drawn ani- mated films in the West and somewhat less-verifiable experiments in Japan. Readers interested in the international influences of earlier visual media such as painting and printmaking on animation should consult Susan J. Napier’s fascinating history of fine arts influences between Japan and Europe, From Impressionism to Anime (2007). 1 Cartoon Internationale 1. For more on the technical specs of the Matsumoto Fragment, see Frederick S. Litten’s “Japanese color animation from ca. 1907 to 1945” available at http:// litten.de/fulltext/color.pdf. 2. Since the mid-2000s, there has been a small but heartening swell of inter- est in recovering and preserving early anime among film conservators and distributors. Some major DVD collections of pre-1945 animation include: Japanese Anime Classic Collection. Tokyo: Digital Meme, 2009 (4 discs, English, Korean, and Chinese subtitles); The Roots of Japanese Anime Until the End of WWII [United States]: Zakka Films, 2008 (English subtitles); Ōfuji Noburō Collected Works. -

Wartime Ideology and the American Animated Cartoon

WARTIME IDEOLOGY AND THE AMERICAN ANIMATED CARTOON by ELLE KWOK-YIN TING B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1998 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2000 © Elle Kwok-Yin Ting, 2000 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of g/v^i/s// The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date -^Epy-ZM^eR 1ST, 9^0° DE-6 (2/88) Abstract The animated film serves as a means for interrogating the political and social ideologies which influenced its development; features of its construction and aesthetics also gesture towards the historical and psychological factors affecting its production, albeit indirectly. This paper investigates the use of the animated cartoon as a medium for transmitting propaganda in America during the Second World War between the years 1941 and 1945; specifically, it examines the animated cartoon as documentation of homefront psychology in the Second World War, and includes an historical overview of Hollywood animation in addition to a critical analysis of both the cartoon propaganda aesthetic and the psychological factors shaping the design and dissemination of propaganda in entertainment media. -

Academic Catalog 2020-2021

Istituto Lorenzo de’ Medici THE ITALIAN INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FLORENCE | TUSCANIA LdM Italy Main Office Florence Via Faenza, 43 50123 Florence, Italy Phone: +39.055.287.360 Phone: +39.055.287.203 Fax: +39.055.239.8920 LdM Academic Relations and Student Services 3600 Bee Caves Road, Suite 205B Austin, TX 78746 US Phone: +1.877.765.4LDM (4536) Phone: +1.512.328.INFO (4636) Fax: +1.512.328.4638 [email protected] www.ldminstitute.com L d M ACADEMIC CATALOG 2020 / 2021 MB 1 L d M ACADEMIC CATALOG 2020 / 2021 Milan Venice Turin FLORENCE Bologna Region: Tuscany TUSCANIA Closest airports: Genoa Peretola Airport, Pisa Airport Region: Lazio Main railway station: Ancona Closest airport: Santa Maria Novella Fiumicino Airport Rome: 232 km / 144 mi Adriatic Sea Closest railway stations: Tuscania: 159.4 km / 99 mi Viterbo, Tarquinia Daily bus connections to: ROME Viterbo, Tarquinia Capital Rome: 77.6 km / 48.2 mi ■ Florence: 159.4 km / 99 mi Napels Tyrrhenian Coast: 30 km / 18.6 mi Sassari Matera Lecce Tyrrhenian Sea Cagliari Palermo Catania I CHOSE TO STUDY AT Ld M BECAUSE OF THE DIVERSITY OF ITS EDUCATIONAL OFFER. EVERY CLASS CHALLENGED ME IN THE BEST WAY. I ALWAYS WANTED TO LEARN MORE, AND THE PROFESSORS ARE OUTSTANDING. I WILL ALWAYS BE GRATEFUL FOR THIS EXPERIENCE, WHICH HELPED ME OVERCOME MY PERSONAL GOALS AND INSPIRED ME TO TRULY BECOME A GLOBAL CITIZEN. - Adriana C, LdM Florence L d M ACADEMIC CATALOG 2020 / 2021 2 3 L d M ACADEMIC CATALOG 2020 / 2021 INDEX 1 GENERAL INFORMATION 4 1.1 Application Deadlines and Academic Calendar 4 1.2 Mission -

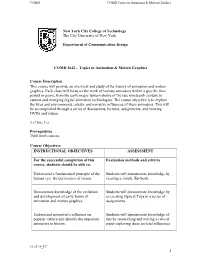

COMD 3642 – Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics

COMD COMD Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics New York City College of Technology The City University of New York Department of Communication Design COMD 3642 – Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics Course Description This course will provide an overview and study of the history of animation and motion graphics. Each class will focus on the work of various animators within a specific time period or genre, from the early magic lantern shows of the late nineteenth century to current and emerging digital animation technologies. The course objective is to explore the lives and environments, artistic and narrative influences of these animators. This will be accomplished through a series of discussions, lectures, assignments, and viewing DVDs and videos. 3 cl hrs, 3 cr Prerequisites 3500 level courses Course Objectives INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES ASSESSMENT For the successful completion of this Evaluation methods and criteria course, students should be able to: Understand a fundamental principle of the Students will demonstrate knowledge by human eye: the persistence of vision. creating a simple flip-book. Demonstrate knowledge of the evolution Students will demonstrate knowledge by and development of early forms of re-creating Optical Toys in a series of animation and motion graphics. assignments. Understand animation's influence on Students will demonstrate knowledge of popular culture and identify the important this by researching and writing a critical animators in history. paper exploring these societal influences. 10.25.14_LC 1 COMD COMD Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES ASSESSMENT Define the major innovations developed by Students will demonstrate knowledge of Disney Studios. these innovations through discussion and research.