Up, up and Across: Superman, the Second World War and the Historical Development of Transmedia Storytelling’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

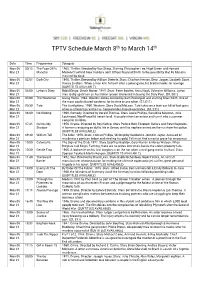

TPTV Schedule March 8Th to March 14Th

th th TPTV Schedule March 8 to March 14 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 08 00:15 The Face Of Fu 1965. Thriller. Directed by Don Sharp. Starring Christopher Lee, Nigel Green and Howard Mar 21 Manchu Marion-Crawford. New murders alert Officer Nayland Smith to the possibility that Fu Manchu may not be dead. Mon 08 02:05 Dark City 1950. Thriller. Directed by William Dieterle. Stars: Charlton Heston, Dean Jagger, Lizabeth Scott, Mar 21 Viveca Lindfors. When a man kills himself after a poker game, his brother looks for revenge. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 08 04:00 Lytton's Diary Rabid Dingo: Shock Horror. 1985. Stars: Peter Bowles, Anna Nygh, Sylvester Williams. Lytton Mar 21 tries to dig up dirt on an Australian tycoon interested in buying the Daily Post. (S1, E01) Mon 08 05:00 The Westerner Going Home. 1962. Western Series created by Sam Peckinpah and starring Brian Keith. One of Mar 21 the most sophisticated westerns for its time or any other. (S1, E11) Mon 08 05:30 Tate The Gunfighters. 1960. Western. Stars David McLean. Tate takes on a train car full of fast guns Mar 21 when a simmering rancher vs. homesteader dispute escalates. (S1, E11) Mon 08 06:00 No Kidding 1960. Comedy. Directed by Gerald Thomas. Stars Leslie Phillips, Geraldine Mcewan, Julia Mar 21 Lockwood, Noel Purcell & Irene Handl. A couple inherit an estate and turn it into a summer camp for children. Mon 08 07:45 Guilt Is My 1950. Drama. Directed by Roy Kellino. Stars Patrick Holt, Elizabeth Sellars and Peter Reynolds. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

SAV THE BEST IN COMICS & E LEGO ® PUBLICATIONS! W 15 HEN % 1994 --2013 Y ORD OU ON ER LINE FALL 2013 ! AMERICAN COMIC BOOK CHRONICLES: The 1950 s BILL SCHELLY tackles comics of the Atomic Era of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley: EC’s TALES OF THE CRYPT, MAD, CARL BARKS ’ Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge, re-tooling the FLASH in Showcase #4, return of Timely’s CAPTAIN AMERICA, HUMAN TORCH and SUB-MARINER , FREDRIC WERTHAM ’s anti-comics campaign, and more! Ships August 2013 Ambitious new series of FULL- (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 COLOR HARDCOVERS (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490540 documenting each 1965-69 decade of comic JOHN WELLS covers the transformation of MARVEL book history! COMICS into a pop phenomenon, Wally Wood’s TOWER COMICS , CHARLTON ’s Action Heroes, the BATMAN TV SHOW , Roy Thomas, Neal Adams, and Denny O’Neil lead - ing a youth wave in comics, GOLD KEY digests, the Archies and Josie & the Pussycats, and more! Ships March 2014 (224-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $39.95 (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 9781605490557 The 1970s ALSO AVAILABLE NOW: JASON SACKS & KEITH DALLAS detail the emerging Bronze Age of comics: Relevance with Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams’s GREEN 1960-64: (224-pages) $39.95 • (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-045-8 LANTERN , Jack Kirby’s FOURTH WORLD saga, Comics Code revisions that opens the floodgates for monsters and the supernatural, 1980s: (288-pages) $41.95 • (Digital Edition) $13.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-046-5 Jenette Kahn’s arrival at DC and the subsequent DC IMPLOSION , the coming of Jim Shooter and the DIRECT MARKET , and more! COMING SOON: 1940-44, 1945-49 and 1990s (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 • (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490564 • Ships July 2014 Our newest mag: Comic Book Creator! ™ A TwoMorrows Publication No. -

Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko

Law Text Culture Volume 16 Justice Framed: Law in Comics and Graphic Novels Article 10 2012 Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Swinburne University of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Bainbridge, Jason, Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko, Law Text Culture, 16, 2012, 217-242. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Abstract The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. This relationship has also informed superhero comics themselves – going all the way back to Superman’s debut in Action Comics 1 (June 1938). As DC President Paul Levitz says of the development of the superhero: ‘There was an enormous desire to see social justice, a rectifying of corruption. Superman was a fulfillment of a pent-up passion for the heroic solution’ (quoted in Poniewozik 2002: 57). This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Spider-Man, The Question and the Meta-Zone: Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Bainbridge Introduction1 The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. -

The Weekly Whaler PUBLISHED by MS

The Weekly Whaler PUBLISHED BY MS. RODERICK’S LINCOLN ELEMENTARY 21ST CENTURY 3rd GRADE CLASS. No. 11. Vol. XVll. SUNDAY, JULY 8, 1860. (Two Dollars per annum, ( Payable in advance. SHIPS OUT AT SEA. Captain Scarleth’s, ‘The Skittles’ AMERICAN VESSEL is making its way through the SUNK. Captain Vessel Pacific. She wants to head to the Azores. Written By Serena Asa ‘The Batman’ Captain Gabriella is leading ‘The The American whaler Essex hailed Serena ‘The Flamingo’ CoCo’ on its maiden voyage. It is from Nantucket, Massachusetts. It was attacked by 80-ton sperm Isaiah ‘The Resses’ whaling in the Atlantic Ocean. whale. The 20 crew members Kayanda ‘Oreo Ice Cream’ ‘The Dolphin’ and the ‘Cookie escaped in 3 boats, only 5 men survived. Three other men were Crumb’ are headed to the Arctic saved later. The first capture Elias ‘The Sharky’ under the control of Captains sperm whale, by the mid18th Nevaeh and Carina. Emily ‘The Oreo’ century. Herman Melville’s classic novel Moby Dick (1851) was Scarleth ‘The Skittles’ Ms. Roderick and Ian are leading inspired in part by the Story of the their ships, ‘The Sprinkles’ and Essex. Gabriella ‘The CoCo’ ‘The Bentley’ through the North Atlantic Ocean, in search of Right The End. Nevaeh ‘The Dolphin’ Whales. CHARLES W. MORGAN. Carina ‘Cookie Crumb’ ADVERTISEMENTS. Written By Gabriella Ms Roderick ‘The Sprinkles’ LEANOR CISNEROS The last wooden whale ship went back to sea at the Mystic Seaport. Ian ‘The Bentley’ She needed to get fixed up and it took five years. After that, she went on her 38th voyage. -

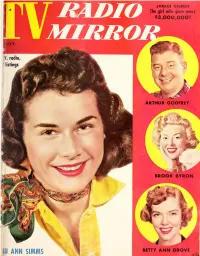

Radio TV Mirror

JANICE GILBERT The girl who gave away MIRRO $3,000,000! ARTHUR GODFREY BROOK BYRON BETTY LU ANN SIMMS ANN GROVE ! ^our new Lilt home permaTient will look , feel and stay like the loveliest naturally curly hair H.1 **r Does your wave look as soft and natural as the Lilt girl in our picture? No? Then think how much more beautiful you can be, when you change to Lilt with its superior ingredients. You'll be admired by men . envied by women ... a softer, more charming you. Because your Lilt will look, feel and stay like naturally curly hair. Watch admiring eyes light up, when you light up your life with a Lilt. $150 Choose the Lilt especially made for your type of hair! plus tax Procter £ Gambles new Wt guiJ. H Home Permanent tor hard-to-wave hair for normal hair for easy-to-wave hair for children's hair — . New, better way to reduce decay after eating sweets Always brush with ALL- NEW IPANA after eating ... as the Linders do . the way most dentists recommend. New Ipana with WD-9 destroys tooth-decay bacteria.' s -\V 77 If you eat sweet treats (like Stasia Linder of Massa- Follow Stasia Linder's lead and use new Ipana regularly pequa, N. Y., and her daughter Darryl), here's good news! after eatin g before decay bacteria can do their damage. You can do a far better job of preventing cavities by Even if you can't always brush after eating, no other brushing after eatin g . and using remarkable new Ipana tooth paste has ever been proved better for protecting Tooth Paste. -

French Animation History Ebook

FRENCH ANIMATION HISTORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Neupert | 224 pages | 03 Mar 2014 | John Wiley & Sons Inc | 9781118798768 | English | New York, United States French Animation History PDF Book Messmer directed and animated more than Felix cartoons in the years through This article needs additional citations for verification. The Betty Boop cartoons were stripped of sexual innuendo and her skimpy dresses, and she became more family-friendly. A French-language version was released in Mittens the railway cat blissfully wanders around a model train set. Mat marked it as to-read Sep 05, Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. In , Max Fleischer invented the rotoscope patented in to streamline the frame-by-frame copying process - it was a device used to overlay drawings on live-action film. First Animated Feature: The little-known but pioneering, oldest-surviving feature-length animated film that can be verified with puppet, paper cut-out silhouette animation techniques and color tinting was released by German film-maker and avante-garde artist Lotte Reiniger, The Adventures of Prince Achmed aka Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed , Germ. Books 10 Acclaimed French-Canadian Writers. Rating details. Dave and Max Fleischer, in an agreement with Paramount and DC Comics, also produced a series of seventeen expensive Superman cartoons in the early s. Box Office Mojo. The songs in the series ranged from contemporary tunes to old-time favorites. He goes with his fox terrier Milou to the waterfront to look for a story, and finds an old merchant ship named the Karaboudjan. The Fleischers launched a new series from to called Talkartoons that featured their smart-talking, singing dog-like character named Bimbo. -

The Diamond of Psi Upsilon Mar 1951

THE DIAMOND OF PSI UPSILON MARCH, 1951 VOLUME XXXVll NUMBER THREE Clayton ("Bud") Collyer, Delta Delta '31, Deacon and Emcee (See Psi U Personality of the Month) The Diamond of Psi Upsilon OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF PSI UPSILON FRATERNITY Volume XXXVll March, 1951 Number 3 AN OPEN FORUiM FOR THE FREE DISCUSSION OF FRATERNITY MATTERS IN THIS ISSUE Page Psi U Personality of the Month 70 The 118th National Convention Program 71 Highlights in the Mu's History 72 The University of Minnesota 74 The Archives 76 The Psi Upsilon Scene 77 Psi U's in the Civil War 78 Psi U Lettermen 82 Pledges and Recent Initiates 83 The Chapters Speak 88 The Executive Council and Alumni Association, Officers and Mem bers 100 Roll of Chapters and Alumni Presidents Cover III General Information Cover IV EDITOR Edward C. Peattie, Phi '06 ALUMNI EDITOR David C. Keutgen, Lambda '42 ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON THE DIAMOND J. J. E. Hessey, Nu '13, Chairman Herbert J. Flagg, Theta Theta '12 Walter S. Robinson, Lambda '19 A. Northey Jones, Beta Beta '17 S. Spencer Scott, Phi '14 (ex-officio) LeRoy J. Weed, Theta '01 Oliver B. Merrill, Jr., Gamma '25 (ex-officio) Publication Office, 450 Ahnaip St., Menasha, Wis. Executive and Editorial Offices Room 510, 420 Lexington Ave., New York 17, N.Y. Life Subscription, $15; By Subscription, $1.00 per year; Single Copies, 50 cents Published in November, January, March and June by the Psi Upsilon Fraternity. Entered as Second Class Matter January 8, 1936, at the Post Office at Menasha, Wisconsin, under the Act of August 24, 1912. -

MAY 4 Quadracci Powerhouse

APRIL 8 – MAY 4 Quadracci Powerhouse By David Bar Katz | Directed by Mark Clements Judy Hansen, Executive Producer Milwaukee Repertory Theater presents The History of Invulnerabilty PLAY GUIDE • Play Guide written by Lindsey Hoel-Neds Education Assistant With contributions by Margaret Bridges Education Intern • Play Guide edited by Jenny Toutant Education Director MARK’S TAKE Leda Hoffmann “I’ve been hungry to produce History for several seasons. Literary Coordinator It requires particular technical skills, and we’ve now grown our capabilities such that we can successfully execute this Lisa Fulton intriguing exploration of the life of Jerry Siegel and his Director of Marketing & creation, Superman. I am excited to build, with my wonder- Communications ful creative team, a remarkable staging of this amazing play that will equally appeal to theater-lovers and lovers of comic • books and superheroes.”” -Mark Clements, Artistic Director Graphic Design by Eric Reda TABLE OF CONTENTS Synopsis ....................................................................3 Biography of Jerry Siegel. .5 Biography of Superman .....................................................5 Who’s Who in the Play .......................................................6 Mark Clements The Evolution of Superman. .7 Artistic Director The Golem Legend ..........................................................8 Chad Bauman The Übermensch ............................................................8 Managing Director Featured Artists: Jef Ouwens and Leslie Vaglica ...............................9 -

Hearing Voices

January 4 - 10, 2020 www.southernheatingandac.biz/ Hearing $10.00 OFF voices any service call one per customer. Jane Levy stars in “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist” 910-738-70002105-A EAST ELIZABETHTOWN RD CARDINAL HEART AND VASCULAR PLLC Suriya Jayawardena MD. FACC. FSCAI Board Certified Physician Heart Disease, Leg Pain due to poor circulation, Varicose Veins, Obesity, Erectile Dysfunction and Allergy clinic. All insurances accepted. Same week appointments. Friendly Staff. Testing done in the same office. Plan for Healthy Life Style 4380 Fayetteville Rd. • Lumberton, NC 28358 Tele: 919-718-0414 • Fax: 919-718-0280 • Hours of Operation: 8am-5pm Monday-Friday Page 2 — Saturday, January 4, 2020 — The Robesonian A penny for your songs: ‘Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist’ premieres on NBC By Sachi Kameishi like “Glee” and “Crazy Ex-Girl- narrates the first trailer for the One second, Zoey’s having a ters who transition from dialogue chance to hear others’ innermost TV Media friend” and a stream of live-ac- show, “... what she got, was so regular conversation with her to song as though it were noth- thoughts through music, a lan- tion Disney remakes have much more.” best friend, Max, played by Skylar ing? Taking it at face value, peo- guage as universal as they come f you’d told me a few years ago brought the genre back into the In an event not unlike your Astin (“Pitch Perfect,” 2012). ple singing and dancing out of — a gift curious in that it sends Ithat musicals would be this cul- limelight, and its rebirth spans standard superhero origin story, Next thing she knows, he’s sing- nowhere is very off-putting and her on a journey that doesn’t nec- turally relevant in 2020, I would film, television, theater and pod- an MRI scan gone wrong leaves ing and dancing to the Jonas absurd, right? Well, “Zoey’s Ex- essarily highlight her own voice have been skeptical. -

I'm Sorry by Jack Prelutsky

Name: I’m Sorry Poetry by Jack Prelutsky I’m sorry I squashed a banana in bed, I’m sorry I bandaged a whole loaf of bread, I’m sorry I pasted the prunes to your pants, I’m sorry I brought home the ants. I’m sorry for letting the dog eat the broom, I’m sorry for freeing a frog in your room, I’m sorry I wrote on the wall with sardines, I’m sorry I sat on the beans. I’m sorry for putting the peas in my hair, I’m sorry for leaving the eggs on your chair, I’m sorry for tying a can to the cat, I’m sorry for being a brat! “I’m Sorry” © 1990 by Jack Prelutsky from Something Big Has Been Here by Jack Prelutsky, used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers. ™ 4 Being a Writer © Developmental Studies Center Unit 1 Week 3 Day 3 Project Name: Being a Writer Grade 4 Student Book Project Name: Being a Writer Grade 4 Student Book Round: FINAL Date: 09/25/07 Round: FINAL Date: 09/25/07 File Name: BAW_SB_G4_whole.indd Page #: 4 File Name: BAW_SB_G4_whole.indd Page #: 5 Trim size: 8.375” x 10.875” Colors used: PMS 2622 Printed at: 100% Trim size: 8.375” x 10.875” Colors used: PMS 2622 Printed at: 100% Artist: Scott Benoit Editor: Amy Bauman Artist: Scott Benoit Editor: Amy Bauman Comments: Comments: Name: I’m Much Too Tired to Play Tonight Poetry by Jack Prelutsky I’m much too tired to play tonight, I’m much too tired to talk, I’m much too tired to pet the dog or take him for a walk, I’m much too tired to bounce a ball, I’m much too tired to sing, I’m much too tired to try to think about a single thing. -

TPTV Schedule March 1St to March 7Th

st th TPTV Schedule March 1 to March 7 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 01 00:05 King David 1985. Drama. Directed by Bruce Beresford. Stars Richard Gere, Alice Krige, Denis Quilley & Mar 21 Edward Woodward. Epic historical drama about the life of the second King of the Kingdom of Israel, David. (AVAILABLE SUBTITLES) Mon 01 02:15 The Immortal Orson 2019. Documentary. Director: Chris Wade. Stars: Dorian Bond, Norman Eshley & Henry Jaglom. Mar 21 Welles A documentary exploring the life and career of the esteemed Orson Welles. Mon 01 03:30 The Hideout 1956. Drama. Director: Peter Graham Scott. Cast: Dermot Walsh, Rona Anderson & Sam Kydd. Mar 21 An insurance investigator receives a suitcase full of cash. His search leads him to the sister of a smuggler. Mon 01 04:45 The Girl From Willow 1975. Drama. Director: Gay Ashby. A man offers a young woman a lift, only to discover later Mar 21 Green that she went missing two years ago. Part of the Women Amateur Filmmakers Collection. Mon 01 05:00 The Westerner Line Camp. 1962. Western Series created by Sam Peckinpah and starring Brian Keith. One of Mar 21 the most sophisticated westerns for its time or any other. (S1, E10) Mon 01 05:30 Tate The Reckoning. 1960. Western. Stars David McLean. The adventures of a one-armed gun Mar 21 fighter who lost his arm in the Civil War. (S1, E10) Mon 01 06:00 Blind Corner 1965. Drama. Director: Lance Comfort. Stars William Sylvester, Barbara Shelley & Elizabeth Mar 21 Shepherd. The wife of a blind composer plots to murder her husband after he learns of her affair.