Wartime Ideology and the American Animated Cartoon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Thing One!] Oh the Places He Went! Yes, There Really Was a Dr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3069/thing-one-oh-the-places-he-went-yes-there-really-was-a-dr-3069.webp)

[Thing One!] Oh the Places He Went! Yes, There Really Was a Dr

There’s Fun to Be Done! [Thing One!] Oh The Places He Went! Yes, there really was a Dr. Seuss. He was not an official doctor, but his Did You Know? prescription for fun has delighted readers for more than 60 years. The proper pronunciation of “Seuss” is Theodor Seuss Geisel (“Ted”) was actually “Zoice” (rhymes with “voice”), being born on March 2, 1904, in a Bavarian name. However, due to the fact Springfield, Massachusetts. His that most Americans pronounced it father, Theodor Robert, and incorrectly as “Soose”, Geisel later gave in grandfather were brewmasters and stopped correcting people, even quipping (joking) the mispronunciation was a (made beer) and enjoyed great financial success for many good thing because it is “advantageous for years. Coupling the continual threats of Prohibition an author of children’s books to be (making and drinking alcohol became illegal) and World associated with—Mother Goose.” War I (where the US and other nations went to war with Germany and other nations), the German-immigrant The character of the Cat in “Cat in the Hat” Geisels were targets for many slurs, particularly with and the Grinch in “How the Grinch Stole regard to their heritage and livelihoods. In response, they Christmas” were inspired by himself. For instance, with the Grinch: “I was brushing my were active participants in the pro-America campaign of teeth on the morning of the 26th of last World War I. Thus, Ted and his sister Marnie overcame December when I noted a very Grinch-ish such ridicule and became popular teenagers involved in countenance in the mirror. -

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

The Disney Strike of 1941: from the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, Ljohnson [email protected]

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2008 The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Labor Relations Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Lisa, "The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective" (2008). Honors Projects Overview. 17. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/17 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective An Undergraduate Honors Project Presented By Lisa Johnson To The Department of History Approved: Project Advisor Date Chair, Department Honors Committee Date Department Chair Date The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective By Lisa Johnson An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in The Department of History The School of the Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2008 1 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 I. The Strike Page 5 II. The Unheard Struggles for Control: Intellectual Property Rights, Screen Credit, Workplace Environment, and Differing Standards of Excellence Page 17 III. The Historiography Page 42 Afterword Page 56 Bibliography Page 62 2 Introduction On May 28 th , 1941, seventeen artists were escorted out of the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California. -

Filosofická Fakulta Masarykovy Univerzity

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Magisterská diplomová práce Erika F eldová 2020 Erika Feldová 20 20 Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies North American Culture Studies Erika Feldová From the War Propagandist to the Children’s Book Author: The Many Faces of Dr. Seuss Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Smith, M.A, Ph. D. 2020 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature Acknowledgement I would like to thank my family and friends for supporting me throughout my studies. I could never be able to do this without you all. I would also like to thank Jeffrey Alan Smith, M.A, Ph. D. for all of his help and feedback. Erika Feldová 1 Contents From The War Propagandist to the Children’s Book Author: the Many Faces of Dr. Seuss............................................................................................................................. 0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 2 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 5 Geisel and Dr. Seuss ..................................................................................................... 7 Early years .................................................................................................................. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

The Cat in the Hat Study Guide

Main Street Theater for Youth Study Guide MainStreetTheater.com 713-524-9196 TheThe Cat in the HatCat TEACHERS FOR TEACHERS in the Hat We hope these supplemental materials will help you integrate your field trip into your classroom curriculum. We’ve included a number of activities and resources to help broaden your students’ experience. Please make sure that each teacher that will be attending the play has a copy of these materials as they prepare to see the show. ESTIMATED LENGTH OF SHOW: 45 MINUTES Have students write letters or draw pictures to the cast of THE CAT IN THE HAT with their thoughts and comments on the production! All correspondence should be sent to: SCHOOL BOOKINGS Main Street’s Theater for Youth 3400 Main Street #283 Houston, Texas 77002 Educational materials produced by Philip Hays and Vivienne St. John The Cat READ THE BOOK in the Hat Read The Cat in the Hat to your class before seeing the play! Point out the title and explain that it is the name of the book. Have your students name some other book titles. Point out the author’s name and explain that they are the one who wrote the book. Start by having the students look at the pictures. Ask them what they think the story is about. Remind them to use the pictures as clues. If they can, have them take turns reading. After reading the book, ask the students: What is their favorite part of the story? Did they think the story was make believe (fiction) or was it real (non-fiction)? The Cat ABOUT THE AUTHOR in the Hat WHO WROTE THE CAT IN THE HAT? streets of Springfield. -

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin's Influence on American

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin’s Influence on American Animation By Nancy Beiman SLIDE 1: Joe Grant trading card of Chaplin and Mickey Mouse Charles Chaplin became an international star concurrently with the birth and development of the animated cartoon. His influence on the animation medium was immense and continues to this day. I will discuss how American character animators, past and present, have been inspired by Chaplin’s work. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND (SLIDE 2) Jeffrey Vance described Chaplin as “the pioneer subject of today’s modern multimedia marketing and merchandising tactics”, 1 “(SLIDE 3). Charlie Chaplin” comic strips began in 1915 and it was a short step from comic strips to animation. (SLIDE 4) One of two animated Chaplin series was produced by Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan Studios in 1918-19. 2 Immediately after completing the Chaplin cartoons, (SLIDE 5) Otto Messmer created Felix the Cat who was, by 1925, the most popular animated character in America. Messmer, by his own admission, based Felix’s timing and distinctive pantomime acting on Chaplin’s. 3 But no other animators of the time followed Messmer’s lead. (SLIDE 6) Animator Shamus Culhane wrote that “Right through the transition from silent films to sound cartoons none of the producers of animation paid the slightest attention to… improvements in the quality of live action comedy. Trapped by the belief that animated cartoons should be a kind of moving comic strip, all the producers, (including Walt Disney) continued to turn out films that consisted of a loose story line that supported a group of slapstick gags which were often only vaguely related to the plot….The most astonishing thing is that Walt Disney took so long to decide to break the narrow confines of slapstick, because for several decades Chaplin, Lloyd and Keaton had demonstrated the superiority of good pantomime.” 4 1 Jeffrey Vance, CHAPLIN: GENIUS OF THE CINEMA, p. -

What Can a Cartoon Tell Us About the US Military in World War

Primary Source Volume IV: Issue II Page 1 Private Snafu: What Can a Cartoon Tell Us About the U.S. Military in World War II? KEENAN SALLA n the field of military history, where so much study is focused on devastating technologies, brilliant strategies and Imonumental battlefields, it may seem odd to approach the study of the U.S. military inWorld War II by examin- ing something as seemingly innocuous as a series of animated cartoon shorts like Private Snafu. While studying the history of WWII through the scope of military propaganda may seem less odd to some, particularly those who are familiar with it, it may seem unconventional to focus on the esoteric Private Snafu over a grander, and more well know series, such as Why We Fight. Framed in one of the most popular forms of contemporary mass media, the Pri- vate Snafu shorts produced by the U.S. Army and Warner Brothers Studios during the war serve as a unique window into both the concerns of the World War II U.S. military command structure and the culture and composition of the enlisted military. The concerns of the military command structure, such as enforcing discipline and the dissemination of in- formation, are plainly illustrated by the content of the Snafu shorts. Along with hundreds of other training films and other forms of newly arrived mass media, Private Snafu would be part of one of the most rapid troop mobilizations in military history. However, one the most interesting facets of the Private Snafu shorts is that while they were never made for public consumption, but instead were considered secret military material that was only to be shown to the members of the armed forces, they also featured many of the same popular cultural references and comedic tropes of civilian animation. -

Cartooning America: the Fleischer Brothers Story

NEH Application Cover Sheet (TR-261087) Media Projects Production PROJECT DIRECTOR Ms. Kathryn Pierce Dietz E-mail: [email protected] Executive Producer and Project Director Phone: 781-956-2212 338 Rosemary Street Fax: Needham, MA 02494-3257 USA Field of expertise: Philosophy, General INSTITUTION Filmmakers Collaborative, Inc. Melrose, MA 02176-3933 APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Cartooning America: The Fleischer Brothers Story Grant period: From 2018-09-03 to 2019-04-19 Project field(s): U.S. History; Film History and Criticism; Media Studies Description of project: Cartooning America: The Fleischer Brothers Story is a 60-minute film about a family of artists and inventors who revolutionized animation and created some of the funniest and most irreverent cartoon characters of all time. They began working in the early 1900s, at the same time as Walt Disney, but while Disney went on to become a household name, the Fleischers are barely remembered. Our film will change this, introducing a wide national audience to a family of brothers – Max, Dave, Lou, Joe, and Charlie – who created Fleischer Studios and a roster of animated characters who reflected the rough and tumble sensibilities of their own Jewish immigrant neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York. “The Fleischer story involves the glory of American Jazz culture, union brawls on Broadway, gangsters, sex, and southern segregation,” says advisor Tom Sito. Advisor Jerry Beck adds, “It is a story of rags to riches – and then back to rags – leaving a legacy of iconic cinema and evergreen entertainment.” BUDGET Outright Request 600,000.00 Cost Sharing 90,000.00 Matching Request 0.00 Total Budget 690,000.00 Total NEH 600,000.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Ms. -

Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation Within American Tap Dance Performances of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 © Copyright by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 by Brynn Wein Shiovitz Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950, looks at the many forms of masking at play in three pivotal, yet untheorized, tap dance performances of the twentieth century in order to expose how minstrelsy operates through various forms of masking. The three performances that I examine are: George M. Cohan’s production of Little Johnny ii Jones (1904), Eleanor Powell’s “Tribute to Bill Robinson” in Honolulu (1939), and Terry- Toons’ cartoon, “The Dancing Shoes” (1949). These performances share an obvious move away from the use of blackface makeup within a minstrel context, and a move towards the masked enjoyment in “black culture” as it contributes to the development of a uniquely American form of entertainment. In bringing these three disparate performances into dialogue I illuminate the many ways in which American entertainment has been built upon an Africanist aesthetic at the same time it has generally disparaged the black body. -

KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin with Leah Wilson

Other Titles in the Smart Pop Series Taking the Red Pill Science, Philosophy and Religion in The Matrix Seven Seasons of Buffy Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Television Show Five Seasons of Angel Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Vampire What Would Sipowicz Do? Race, Rights and Redemption in NYPD Blue Stepping through the Stargate Science, Archaeology and the Military in Stargate SG-1 The Anthology at the End of the Universe Leading Science Fiction Authors on Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Finding Serenity Anti-heroes, Lost Shepherds and Space Hookers in Joss Whedon’s Firefly The War of the Worlds Fresh Perspectives on the H. G. Wells Classic Alias Assumed Sex, Lies and SD-6 Navigating the Golden Compass Religion, Science and Dæmonology in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials Farscape Forever! Sex, Drugs and Killer Muppets Flirting with Pride and Prejudice Fresh Perspectives on the Original Chick-Lit Masterpiece Revisiting Narnia Fantasy, Myth and Religion in C. S. Lewis’ Chronicles Totally Charmed Demons, Whitelighters and the Power of Three An Unauthorized Look at One Humongous Ape KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin WITH Leah Wilson BENBELLA BOOKS • Dallas, Texas This publication has not been prepared, approved or licensed by any entity that created or produced the well-known movie King Kong. “Over the River and a World Away” © 2005 “King Kong Behind the Scenes” © 2005 by Nick Mamatas by David Gerrold “The Big Ape on the Small Screen” © 2005 “Of Gorillas and Gods” © 2005 by Paul Levinson by Charlie W. -

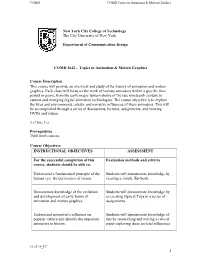

COMD 3642 – Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics

COMD COMD Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics New York City College of Technology The City University of New York Department of Communication Design COMD 3642 – Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics Course Description This course will provide an overview and study of the history of animation and motion graphics. Each class will focus on the work of various animators within a specific time period or genre, from the early magic lantern shows of the late nineteenth century to current and emerging digital animation technologies. The course objective is to explore the lives and environments, artistic and narrative influences of these animators. This will be accomplished through a series of discussions, lectures, assignments, and viewing DVDs and videos. 3 cl hrs, 3 cr Prerequisites 3500 level courses Course Objectives INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES ASSESSMENT For the successful completion of this Evaluation methods and criteria course, students should be able to: Understand a fundamental principle of the Students will demonstrate knowledge by human eye: the persistence of vision. creating a simple flip-book. Demonstrate knowledge of the evolution Students will demonstrate knowledge by and development of early forms of re-creating Optical Toys in a series of animation and motion graphics. assignments. Understand animation's influence on Students will demonstrate knowledge of popular culture and identify the important this by researching and writing a critical animators in history. paper exploring these societal influences. 10.25.14_LC 1 COMD COMD Topics in Animation & Motion Graphics INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES ASSESSMENT Define the major innovations developed by Students will demonstrate knowledge of Disney Studios. these innovations through discussion and research.