Police Liability for Creating the Need to Use Deadly Force in Self-Defense, 86 MICH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lifetime Likelihood of Victimization

U. S. Department of Justice I Bureau of Justice Statistics I Lifetime Likelihood of Victimization by Herbert Koppel people's perception of the meaning of BJS Analyst March 1987 annual rates with respect to their own The Bureau of Justice Statistics lives. If the Earth revolved around the This report provides estimates of the National Crime Survey provides sun in 180 days, all of our annual crime likelihood that a person will become a annual victimization rates based rates would be halved, but we would not victim of crime during his or her life- on counts of the number of crimes be safer. time, or that a household will be vic- reported and not reported to timized during a 20-year period. This police in the United States. These Calculating lifetime victimization rates contrasts with the conventional use of a rates are based on interviews 1-year period in measuring crime and twice a year with about 101,000 For this report, lifetime likelihoods criminal victimization. Most promi- persons in approximately 49,000 of victimization were calculated from nently, the National Crime Survey nationally representative NCS annual victimization rates and life (NCS) surveys a sample of U.S. house- households. Those annual rates, tables published by the National Center holds and publishes annual victimization while of obvious utility to for Health statistics.% The probability rates, and the FBI's Uniform Crime policymakers, researchers, and that a person will be victimized at a Reports (UCR) provide annual rates of statisticians, do not convey to particular age basically depends upon crimes reported to the police. -

Page 243 TITLE 19—CUSTOMS DUTIES § 1592 Possible for Such

Page 243 TITLE 19—CUSTOMS DUTIES § 1592 possible for such merchandise, or any part (4) The external display of false registration thereof, to be introduced into the United numbers, false country of registration, or, in States unlawfully. the case of a vessel, false vessel name. (c) Civil penalties (5) The presence on board of unmanifested merchandise, the importation of which is pro- Any person who violates any provision of this hibited or restricted. section is liable for a civil penalty equal to (6) The presence on board of controlled sub- twice the value of the merchandise involved in stances which are not manifested or which are the violation, but not less than $10,000. The not accompanied by the permits or licenses re- value of any controlled substance included in quired under Single Convention on Narcotic the merchandise shall be determined in accord- Drugs or other international treaty. ance with section 1497(b) of this title. (7) The presence of any compartment or (d) Criminal penalties equipment which is built or fitted out for smuggling. In addition to being liable for a civil penalty (8) The failure of a vessel to stop when under subsection (c) of this section, any person hailed by a customs officer or other govern- who intentionally commits a violation of any ment authority. provision of this section is, upon conviction— (1) liable for a fine of not more than $10,000 (June 17, 1930, ch. 497, title IV, § 590, as added or imprisonment for not more than 5 years, or Pub. L. 99–570, title III, § 3120, Oct. -

Lifetime Likelihood of Victimization

.,. u.s, Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics Lifetime Likelihood of Victimization by Het'bert Koppel people's perception of the meaning of BJS Analyst Mat'ch 1987 annual ra tes with respect to their own The Bureau of Justice Statistics lives. If the Earth revolved around the This report provides estimates of the National Crime Survey provides sun in 180 days, all of our annual crime likelihood that a person will become a annual victimization rates based rates would be halved, but we would not victim of crime during his or her life on counts of the number of crimes be safer. time, or that a household will be vic reported and not reported to timized during a 20-year pel'iod. This police in the United States. These Calculating lifetime victimization fates contrasts with the conventional use of a rates are based on interviews I-year period in measuring crime and twice a year with about lOl,OOO For this report, lifetime likelihoods criminal victimization. Most promi persons in approximately 49,000 of victimization were calculated from nently, the National Crime Survey na tionally representative NCS annual victimi.zation rates and life (NCS) surveys a sample of U.S. house households. Those annual ra ces, tables published by the National Center 2 holds and publishes annual victimization while of obvious utility to for Health Statistics. The probability rates, and the FBI's Uniform Crime policymakel's, researchers, and that a person will be victimized at a Reports (UCR) provide annual rates of statisticians, do not convey to particular age basically depends upon crimes reported to the police. -

Torts in the Oil Patch

Torts in the Oil Patch Prof. Tracy Hester September 11, 2017 Announcements • Field trip to Weatherford drilling rig: Friday, Sept. 29, 2017 • Guest speakers – – Dr. John Nielsen-Gammon, Wednesday, Sept. 13, at 6 pm in BLB 109 – Roger Martella, GE VP for EHS, Wednesday, Oct. 25, time and place TBA – Dr. Gavin Clarkson - November • IEL, AIPN, GCPA Review • Basics of Oilfield E&P • Types of contamination created by E&P work • Categories of likely tort actions • Reasons to pursue tort remedy rather than agency action Environmental Law of First Resort: Tort Claims • Nuisance • Negligence (including negligence per se) • Trespass • Unjust Enrichment • Emotional Distress • Strict Liability – Ultrahazardous Activity • Exotic claims (business torts, civil conspiracy) Likely Parties • Plaintiffs: – Surface estate owners – Neighbors – both surface and mineral estate owners – Agencies and governments – NGOs • Defendants: working interest owners, operators and contractors Duties Owed by Oil Company • Be a reasonably prudent operator • “Restore” the surface ? • plow depth • concrete pads and foundations? • oil, saltwater, etc. contamination? • What else does the lease (contract) say? Nuisance • Material or substantial injury to a person of ordinary health and sensibilities in that particular locale – private vs public nuisance • no statute of limitations if public nuisance • diminution in property value vs injunction or abatement (cost) • yesterday’s economic accommodation may become tomorrow’s nuisance (Texas: to persons of “ordinary” sensibilities) • Permit to discharge is usually not a defense • Permanent, temporary, and/or continuing • “Coming to the nuisance” doctrine may not be applicable if “temporary” and “continuing” Trespass • Conduct that leads to the invasion of a person’s interest in his or her rightful exclusive possession of property • La: unlawful physical invasion of property of another • Typically, intentional tort that requires a showing of fault • Often 2 or 3 year SOL. -

The Truth About Voter Fraud 7 Clerical Or Typographical Errors 7 Bad “Matching” 8 Jumping to Conclusions 9 Voter Mistakes 11 VI

Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non-partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to redistricting reform, from access to the courts to presidential power in the fight against terrorism. A sin- gular institution—part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group—the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advocacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S VOTING RIGHTS AND ELECTIONS PROJECT The Voting Rights and Elections Project works to expand the franchise, to make it as simple as possible for every eligible American to vote, and to ensure that every vote cast is accurately recorded and counted. The Center’s staff provides top-flight legal and policy assistance on a broad range of election administration issues, including voter registration systems, voting technology, voter identification, statewide voter registration list maintenance, and provisional ballots. © 2007. This paper is covered by the Creative Commons “Attribution-No Derivs-NonCommercial” license (see http://creativecommons.org). It may be reproduced in its entirety as long as the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is credited, a link to the Center’s web page is provided, and no charge is imposed. The paper may not be reproduced in part or in altered form, or if a fee is charged, without the Center’s permission. -

2015/16 MIDTERM REPORT Dear Friends

OFFICE OF THE STATE’S ATTORNEY FOR BALTIMORE CITY 2015/16 MIDTERM REPORT Dear Friends, We have reached the halfway point of my first term as State’s Attorney for Baltimore City. Much has changed in Baltimore since the beginning of my administration—we have a new Mayor, a new City Council, a new Police Commissioner, and most importantly, a new approach to fighting crime. When I took office, I promised to repair the broken relationship between the community and law enforcement. I promised to tackle violent crime. And lastly, I promised to reform our criminal justice system using a holistic approach to prosecution. As I look back at all that we’ve accomplished in just two short years, I’m proud to report that we have made significant strides toward fulfilling those three promises: Driving Down Violent Crime • We convicted 433 felony rapists, child molesters and other sexual offenders including 5-time serial rapist Nelson Clifford. • Our Felony Trial Units secured over 5,400 convictions with an average conviction rate of 93 percent. • We secured major convictions in several high profile homicide cases including multiple Public Enemy #1s designated by the Baltimore Police Department (BPD), Bishop Heather Cook who tragically struck and killed Thomas Palermo in 2014, and all of the shooters responsible for the death of one-year-old Carter Scott. • We created a Gun Violence Enforcement Division staffed by prosecutors and BPD detectives co-located at our headquarters that focuses in on gun violence. • We developed the Arrest Alert System, designed by the new Crime Strategies Unit, to alert prosecutors immediately when a targeted individual is arrested for any reason. -

Proof of Fault in Media Defamation Litigation

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 38 Issue 2 Issue 2 - March 1985 Article 1 3-1985 Proof of Fault in Media Defamation Litigation Lackland H. Bloom, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Lackland H. Bloom, Jr., Proof of Fault in Media Defamation Litigation, 38 Vanderbilt Law Review 247 (1985) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol38/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 38 MARCH 1985 NUMBER 2 Proof of Fault in Media Defamation Litigation Lackland H. Bloom, Jr.* I. INTRODUCTION ..................................... 249 II. ACTUAL MALICE .................................... 255 A. Clear and Convincing Evidence ............. 255 B. Knowledge of Falsity ...................... 256 C. Reckless Disregardfor the Truth ........... 259 1. Il1 W ill .............................. 260 2. Failure to Investigate or Verify ........ 264 (a) Lead Time .................... 267 (b) Seriousness of the Charge....... 270 (c) Inherent Improbability ......... 273 (d) Awareness of Inconsistent Infor- m ation ........................ 275 (e) No Source ..................... 277 (f) Obvious Reason to Doubt Source 278 (g) Failure to Consult an Obvious Source ........................ 283 (h) Failure to Consult an Expert ... 285 (i) No Further Verification Following Denial ........................ 286 * Associate Professor of Law, Southern Methodist University. B.A. 1970, Southern Methodist University; J.D. 1973, University of Michigan. I wish to thank Marilyn Lahr, J.D. 1986, Southern Methodist University School of Law, for her valuable assistance and the Southern Methodist University School of Law for its generous support. -

Personal Injury Exclusion: Is the Slashing of Wrists Necessary? Donald J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Akron The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Tax Journal Akron Law Journals 1997 Personal Injury Exclusion: Is the Slashing of Wrists Necessary? Donald J. Zahn Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akrontaxjournal Part of the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation Zahn, Donald J. (1997) "Personal Injury Exclusion: Is the Slashing of Wrists Necessary?," Akron Tax Journal: Vol. 13 , Article 5. Available at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akrontaxjournal/vol13/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Tax Journal by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Zahn: Personal Injury Exclusion PERSONAL INJURY EXCLUSION: IS THE SLASHING OF WRISTS NECESSARY? by DONALD J. ZAHN * "Capital return... in tax accounting,payments received by taxpayer which rep- resent the individual's cost or capitaland hence not taxable as income.' I. INTRODUCTION What do damage awards really represent? Does a damage award stem- ming from a personal injury lawsuit or settlement compensate the individual for lost capabilities? Does a damage award confer a windfall upon that individual? The predecessor statute of section 104(a)(2) of the Internal Revenue Code of 19862 and the policy behind that statute equate damage awards to the wronged individual as a return of capital.3 As years passed, the courts, as well as Congress refined the return of capital concept, expanding the concept to include within its boundaries all forms of personal injury recoveries. -

Res Ipsa Loquitur and Gross Negligence

RES IPSA LOQUITUR AND GROSS NEGLIGENCE I N A DICTUM in the recent case of Garland v.Greenspan,' the Supreme Court of Nevada echoed an apparently unanimous rule2 that the doc- trine of res ipsa loquitur will not raise an inference3 of gross negligence. The facts as found by the trial court sitting without a jury showed that one of the plaintiffs4 was injured when the defendants' automobile swerved to the left of the highway and then to the right, overturning on striking the right shoulder. The defendant driver had lost control of her car for "some unexplained reason" after passing another automobile at a speed in excess of sixty-five miles an hour and in returning to the right-hand line while negotiating a turn to the right. Under the Nevada statute,6 a guest passenger can recover in tort from the host driver only where injury was caused by the driver's in- toxication, wilful misconduct, or gross negligence. The Supreme Court of Nevada, affirming the judgment of the trial court, held that gross neg- ligence or wilful misconduct had not been established as a matter of law, '_Nev.-, 323 P.±d 27 (1958). 'See Harlan v. Taylor, z39 Cal. App. 30, 33 P.zd 422 (934); Lincoln v. Quick, 133 Cal. App. 433, 24 P.2d 245 (1933); O'Reilly v. Sattler, x4i Fla. 770, 193 So. 817 (1940); Minkovitz v. Fine, 67 Ga. App. 176, i9 S.E.zd 561 (1942); Rupe v. Smith, x~i Kan. 6o6, 323 P.zd 293 (x957); Winslow v. Tibbetts, 231 Me. -

Fraud and Scams: a Moving Picture

issue 145 August 2018 1 ombudsman news essential reading for people interested in financial complaints – and how to prevent or settle them fraud and scams: a moving picture It was only relatively recently, in 2015, that we shared our insight into banking complaints involving phone fraud. Back then, it seemed the fact older people were more likely to use landlines meant they were particularly at risk of “no hang up” scams. Caroline Wayman chief ombudsman Today, it’s often loopholes in This makes it harder for us to And as our case studies show, in this issue new technologies, rather than reach an answer both sides are the evolution of criminals’ in old ones, that fraudsters happy with. But it doesn’t mean methods – in particular, ombudsman are using to their advantage. usual standards don’t apply. As their sophisticated use of focus: fraud and Your first step toward being our case studies illustrate, we’ll technology and manipulative scams scammed may be putting your expect to see clear evidence “social engineering” – means page 3 details into an identical, but that banks have investigated it’s an increasingly difficult fake banking website – or thoroughly – and reflected hard case to make. fraud and scams responding to a text message on what more might have been case studies that, on the face of it, looks like done to protect their customers page 8 it’s from your bank. and their money. first quarter Unlike most other complaints We also often hear from banks statistics we see, complaints about fraud that their customers have acted page 14 and scams involve – whether with “gross negligence” – and it’s accepted or suspected – this means they’re not liable for Q&A – our new the actions of a criminal third the money their customer has case-handling party. -

Nuisance – Elements

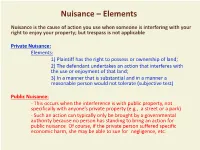

Nuisance – Elements Nuisance is the cause of action you use when someone is interfering with your right to enjoy your property; but trespass is not applicable Private Nuisance: Elements: 1) Plaintiff has the right to possess or ownership of land; 2) The defendant undertakes an action that interferes with the use or enjoyment of that land; 3) In a manner that is substantial and in a manner a reasonable person would not tolerate (subjective test) Public Nuisance: - This occurs when the interference is with public property, not specifically with anyone’s private property (e.g., a street or a park) - Such an action can typically only be brought by a governmental authority because no person has standing to bring an action for public nuisance. Of course, if the private person suffered specific economic harm, she may be able to sue for negligence, etc. Nuisance - Other Factors - The nuisance must have arisen from an act that’s actionable as an intentional, negligent or strict liability tort! - The actions that give rise to the nuisance must be “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Thus: A “balancing test” must be performed between the harm that the nuisance causes and the benefits of the activities that create the nuisance, taking into account: o The economic and social importance of the activity o The burden on the defendant and on society of forcing the activity to cease o Whether there is a more appropriate place to conduct the activity - All the rules regarding causation and damages apply, as with negligence and strict liability - The defenses of assumption of risk and contributory negligence apply; as with any other tort. -

Gross Negligence Or Willful Misconduct" Patrick H

Louisiana Law Review Volume 71 | Number 3 Spring 2011 The BP piS ll and the Meaning of "Gross Negligence or Willful Misconduct" Patrick H. Martin Louisiana State University Law Center Repository Citation Patrick H. Martin, The BP Spill and the Meaning of "Gross Negligence or Willful Misconduct", 71 La. L. Rev. (2011) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol71/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The BP Spill and the Meaning of "Gross Negligence or Wilful Misconduct" PatrickH. Martin* INTRODUCTION The blowout of the Macondo well on April 20, 2010 and the resulting escape of oil into the waters of the Gulf of Mexico and onto the shores of coastal states set in motion numerous lawsuits that will take years to resolve. A significant amount of the liability and penalties arising from the Gulf oil spill will turn on the treatment given to the terms "gross negligence" and "willful misconduct." Should the United States decide to bring a criminal complaint for manslaughter for the lives lost in the accident, "gross negligence" may also be an element in defining the crime. The terms involve interpretation as statutory, contractual, and common law standards. The undertaking is more complex than it might first appear; it will involve courts, arbitrators, and federal agencies. Because of the complexity, some framework for interpretation of the terms may be useful.