Addressing Negligence Claims for Pure Reputational Harm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 243 TITLE 19—CUSTOMS DUTIES § 1592 Possible for Such

Page 243 TITLE 19—CUSTOMS DUTIES § 1592 possible for such merchandise, or any part (4) The external display of false registration thereof, to be introduced into the United numbers, false country of registration, or, in States unlawfully. the case of a vessel, false vessel name. (c) Civil penalties (5) The presence on board of unmanifested merchandise, the importation of which is pro- Any person who violates any provision of this hibited or restricted. section is liable for a civil penalty equal to (6) The presence on board of controlled sub- twice the value of the merchandise involved in stances which are not manifested or which are the violation, but not less than $10,000. The not accompanied by the permits or licenses re- value of any controlled substance included in quired under Single Convention on Narcotic the merchandise shall be determined in accord- Drugs or other international treaty. ance with section 1497(b) of this title. (7) The presence of any compartment or (d) Criminal penalties equipment which is built or fitted out for smuggling. In addition to being liable for a civil penalty (8) The failure of a vessel to stop when under subsection (c) of this section, any person hailed by a customs officer or other govern- who intentionally commits a violation of any ment authority. provision of this section is, upon conviction— (1) liable for a fine of not more than $10,000 (June 17, 1930, ch. 497, title IV, § 590, as added or imprisonment for not more than 5 years, or Pub. L. 99–570, title III, § 3120, Oct. -

Torts in the Oil Patch

Torts in the Oil Patch Prof. Tracy Hester September 11, 2017 Announcements • Field trip to Weatherford drilling rig: Friday, Sept. 29, 2017 • Guest speakers – – Dr. John Nielsen-Gammon, Wednesday, Sept. 13, at 6 pm in BLB 109 – Roger Martella, GE VP for EHS, Wednesday, Oct. 25, time and place TBA – Dr. Gavin Clarkson - November • IEL, AIPN, GCPA Review • Basics of Oilfield E&P • Types of contamination created by E&P work • Categories of likely tort actions • Reasons to pursue tort remedy rather than agency action Environmental Law of First Resort: Tort Claims • Nuisance • Negligence (including negligence per se) • Trespass • Unjust Enrichment • Emotional Distress • Strict Liability – Ultrahazardous Activity • Exotic claims (business torts, civil conspiracy) Likely Parties • Plaintiffs: – Surface estate owners – Neighbors – both surface and mineral estate owners – Agencies and governments – NGOs • Defendants: working interest owners, operators and contractors Duties Owed by Oil Company • Be a reasonably prudent operator • “Restore” the surface ? • plow depth • concrete pads and foundations? • oil, saltwater, etc. contamination? • What else does the lease (contract) say? Nuisance • Material or substantial injury to a person of ordinary health and sensibilities in that particular locale – private vs public nuisance • no statute of limitations if public nuisance • diminution in property value vs injunction or abatement (cost) • yesterday’s economic accommodation may become tomorrow’s nuisance (Texas: to persons of “ordinary” sensibilities) • Permit to discharge is usually not a defense • Permanent, temporary, and/or continuing • “Coming to the nuisance” doctrine may not be applicable if “temporary” and “continuing” Trespass • Conduct that leads to the invasion of a person’s interest in his or her rightful exclusive possession of property • La: unlawful physical invasion of property of another • Typically, intentional tort that requires a showing of fault • Often 2 or 3 year SOL. -

Pp32-33 ABB from May2014 Final

ECM May_Layout 1 02/05/2014 13:38 Page 32 32 Strategy and management Ethical Corporation • May 2014 ANYABERKUT Other section content: p34 Interface's Rob Boogaard p37 Climate action The GlobalEthicist Risk and opportunity – the role of stakeholder trust By Andrea Bonime-Blanc Whether the impact is one you can measure, or something less quantifiable, loss of trust has a lasting effect ontemplating the varieties of reputation administration more deeply focused on national Companies Cchallenge, risk and, yes, opportunity that exist defence and security issues. The trust of stake- for all types of organisation can be overwhelming. holders (or its erosion) is at the core of this operating in There are plenty of questions. What do we reputational hit. the cloud are mean by “reputation”? Whose reputation are we especially talking about? What is “reputation risk”? What is Risk can be contagious “reputation crisis”? What is “reputation opportu- And the reputational reach of the Snowden affair concerned about nity”? hasn’t stopped with the US government. By associ- reputation Reputation risk and opportunity are events that ation, the US technology sector (even companies can hurt or enhance an entity, person, product or not directly involved in creating, developing, imple- service, from the largest entities in the world – the menting or supporting the technologies used in biggest governments, for example – to the tiniest of national security work) has been very concerned entities: small businesses and, of course, people and about the reputational fallout affecting its competi- specific products (if you’re old enough, you’ll tiveness in the global marketplace. -

Proof of Fault in Media Defamation Litigation

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 38 Issue 2 Issue 2 - March 1985 Article 1 3-1985 Proof of Fault in Media Defamation Litigation Lackland H. Bloom, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Lackland H. Bloom, Jr., Proof of Fault in Media Defamation Litigation, 38 Vanderbilt Law Review 247 (1985) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol38/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 38 MARCH 1985 NUMBER 2 Proof of Fault in Media Defamation Litigation Lackland H. Bloom, Jr.* I. INTRODUCTION ..................................... 249 II. ACTUAL MALICE .................................... 255 A. Clear and Convincing Evidence ............. 255 B. Knowledge of Falsity ...................... 256 C. Reckless Disregardfor the Truth ........... 259 1. Il1 W ill .............................. 260 2. Failure to Investigate or Verify ........ 264 (a) Lead Time .................... 267 (b) Seriousness of the Charge....... 270 (c) Inherent Improbability ......... 273 (d) Awareness of Inconsistent Infor- m ation ........................ 275 (e) No Source ..................... 277 (f) Obvious Reason to Doubt Source 278 (g) Failure to Consult an Obvious Source ........................ 283 (h) Failure to Consult an Expert ... 285 (i) No Further Verification Following Denial ........................ 286 * Associate Professor of Law, Southern Methodist University. B.A. 1970, Southern Methodist University; J.D. 1973, University of Michigan. I wish to thank Marilyn Lahr, J.D. 1986, Southern Methodist University School of Law, for her valuable assistance and the Southern Methodist University School of Law for its generous support. -

Tort Recovery for Loss of a Chance David A

University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Fall 2001 Tort Recovery for Loss of a Chance David A. Fischer University of Missouri School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/facpubs Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation David A. Fischer, Tort Recovery for Loss of A Chance, 36 Wake Forest L. Rev. 605 (2001) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. TORT RECOVERY FOR LOSS OF A CHANCE David A- Fischer- "Loss of a chance" is a novel theory of causation commonly used by courts in the United States in medical misdiagnosis cases. Yet, the theory has a vastly broader potential application than this. In fact, it could be applied in virtually every case of questionable causation. While this Article asserts that the doctrine could legitimately be expanded and applied in a variety of additionalsituations, the Article cautions that it would be unwise to apply the doctrine so broadly that it routinely supplants traditional causation rules. The Article searches for a principled basis for limiting the theory within proper bounds by comparing the differing applicationsof the loss of a chance doctrine in British Commonwealth cases and United States cases. The Article concludes that current rationalesfor the doctrine do not provide an adequate limiting principle, but that a case by case policy analysis can appropriatelylimit the theory. -

Report to the Congress on Risk Retention

BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Report to the Congress on Risk Retention October 2010 BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Report to the Congress on Risk Retention Submitted to the Congress pursuant to section 941 of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 October 2010 Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 5 Definitions of Asset Categories .................................................................................... 6 Overview of Securitization ........................................................................................... 8 Mechanics of Asset Sales ................................................................................................... 9 Structure of Securities ...................................................................................................... 10 Incentive and Information Issues in Securitization ..................................................... 14 General Description of Asset Classes ............................................................................ 17 Nonconforming Residential Mortgages ...................................................................... 17 Commercial Mortgages ............................................................................................... 18 Credit Cards -

"Tort" Standards for the Award of Mental Distress Damages in Statutory Discrimination Actions

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 11 1977 Developing "Tort" Standards for the Award of Mental Distress Damages in Statutory Discrimination Actions Harold J. Rennett University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Legal Remedies Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Harold J. Rennett, Developing "Tort" Standards for the Award of Mental Distress Damages in Statutory Discrimination Actions, 11 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 122 (1977). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol11/iss1/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEVELOPING "TORT" STANDARDS FOR THE AWARD OF MENTAL DISTRESS DAMAGES IN STATUTORY DISCRIMINATION ACTIONS Affronts to dignity are compensable by monetary damages for "mental distress" 1 through various tort actions.2 Some courts recently have rec ognized significant similarities between the emotional injury suffered by victims of such "dignitary"3 torts and the emotional injury suffered by persons aggrieved under federal and state discrimination statutes.4 In creasingly, victims of discrimination have sued successfully under these statutes for mental distress damages.5 1 "Mental distress" takes many forms and is referred to by many names. The injury discussed in this article is primarily one that is not caused by physical injury. -

Res Ipsa Loquitur and Gross Negligence

RES IPSA LOQUITUR AND GROSS NEGLIGENCE I N A DICTUM in the recent case of Garland v.Greenspan,' the Supreme Court of Nevada echoed an apparently unanimous rule2 that the doc- trine of res ipsa loquitur will not raise an inference3 of gross negligence. The facts as found by the trial court sitting without a jury showed that one of the plaintiffs4 was injured when the defendants' automobile swerved to the left of the highway and then to the right, overturning on striking the right shoulder. The defendant driver had lost control of her car for "some unexplained reason" after passing another automobile at a speed in excess of sixty-five miles an hour and in returning to the right-hand line while negotiating a turn to the right. Under the Nevada statute,6 a guest passenger can recover in tort from the host driver only where injury was caused by the driver's in- toxication, wilful misconduct, or gross negligence. The Supreme Court of Nevada, affirming the judgment of the trial court, held that gross neg- ligence or wilful misconduct had not been established as a matter of law, '_Nev.-, 323 P.±d 27 (1958). 'See Harlan v. Taylor, z39 Cal. App. 30, 33 P.zd 422 (934); Lincoln v. Quick, 133 Cal. App. 433, 24 P.2d 245 (1933); O'Reilly v. Sattler, x4i Fla. 770, 193 So. 817 (1940); Minkovitz v. Fine, 67 Ga. App. 176, i9 S.E.zd 561 (1942); Rupe v. Smith, x~i Kan. 6o6, 323 P.zd 293 (x957); Winslow v. Tibbetts, 231 Me. -

Fraud and Scams: a Moving Picture

issue 145 August 2018 1 ombudsman news essential reading for people interested in financial complaints – and how to prevent or settle them fraud and scams: a moving picture It was only relatively recently, in 2015, that we shared our insight into banking complaints involving phone fraud. Back then, it seemed the fact older people were more likely to use landlines meant they were particularly at risk of “no hang up” scams. Caroline Wayman chief ombudsman Today, it’s often loopholes in This makes it harder for us to And as our case studies show, in this issue new technologies, rather than reach an answer both sides are the evolution of criminals’ in old ones, that fraudsters happy with. But it doesn’t mean methods – in particular, ombudsman are using to their advantage. usual standards don’t apply. As their sophisticated use of focus: fraud and Your first step toward being our case studies illustrate, we’ll technology and manipulative scams scammed may be putting your expect to see clear evidence “social engineering” – means page 3 details into an identical, but that banks have investigated it’s an increasingly difficult fake banking website – or thoroughly – and reflected hard case to make. fraud and scams responding to a text message on what more might have been case studies that, on the face of it, looks like done to protect their customers page 8 it’s from your bank. and their money. first quarter Unlike most other complaints We also often hear from banks statistics we see, complaints about fraud that their customers have acted page 14 and scams involve – whether with “gross negligence” – and it’s accepted or suspected – this means they’re not liable for Q&A – our new the actions of a criminal third the money their customer has case-handling party. -

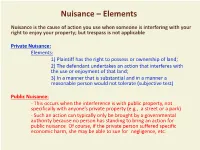

Nuisance – Elements

Nuisance – Elements Nuisance is the cause of action you use when someone is interfering with your right to enjoy your property; but trespass is not applicable Private Nuisance: Elements: 1) Plaintiff has the right to possess or ownership of land; 2) The defendant undertakes an action that interferes with the use or enjoyment of that land; 3) In a manner that is substantial and in a manner a reasonable person would not tolerate (subjective test) Public Nuisance: - This occurs when the interference is with public property, not specifically with anyone’s private property (e.g., a street or a park) - Such an action can typically only be brought by a governmental authority because no person has standing to bring an action for public nuisance. Of course, if the private person suffered specific economic harm, she may be able to sue for negligence, etc. Nuisance - Other Factors - The nuisance must have arisen from an act that’s actionable as an intentional, negligent or strict liability tort! - The actions that give rise to the nuisance must be “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Thus: A “balancing test” must be performed between the harm that the nuisance causes and the benefits of the activities that create the nuisance, taking into account: o The economic and social importance of the activity o The burden on the defendant and on society of forcing the activity to cease o Whether there is a more appropriate place to conduct the activity - All the rules regarding causation and damages apply, as with negligence and strict liability - The defenses of assumption of risk and contributory negligence apply; as with any other tort. -

Safeguarding Reputation

Safeguarding reputation Are you prepared to protect your reputation? 25 November 2020 Safeguarding Reputation: Are you prepared to protect your reputation? Foreword Protecting reputation in the time of uncertainty As the second wave of COVID-19 unravels, many We have identified five key actions that risk owners in organisations find themselves living William organisations need to think about to advance their Shakespeare’s quote from Othello – “Reputation, preparedness to safeguard their reputation. These reputation, reputation! O, I ha' lost my reputation, I ha' include: lost the immortal part of myself, and what remains is - Proactive signal sensing to identify changing bestial!”. Many businesses have gone dark, being social norms or changing narratives among your afraid to say the wrong thing to the media, many others stakeholders have communicated the ‘right thing’ but have not - Building resilience across the whole organisation followed up with the ‘right actions’. As activism to prevent the occurrence of the consequential risk movements become more widespread, this means that of reputation customers and other stakeholders are becoming less - Creating a culture of responsibility throughout forgiving of any corporate missteps. the organisation (reputation can’t be effectively Reputation is a risk of risks. That means that any major managed in a single risk management team) adverse events impacting an organisation can lead to - Training at all levels, including senior executives potential reputational damage. Considering global - Minding your business model to make sure you corporate reputational value is estimated to be trillions understand how each stakeholder group influences of US dollars, a colossal amount of corporate value is your business success at stake. -

Reputational Risk Management

International Journal of Contemporary Management Volume 17 (2018) Number 4, pp. 323–336 doi:10.4467/24498939IJCM.18.049.10035 www.ejournals.eu/ijcm REPUTATIONAL RISK MANAGEMENT Jan Krzysztof Solarz* http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6528-7645 Abstract Background. Reputational risk cross building competitive position or mark management. Shareholders of reputational risk management are more heterogenic. Therefore, it is not surprising that managing reputational risk has now become a major preoccupation for business in the private, public and not-for profits sectors. Research aims. The reputational risk is placed at the top of the risk hierarchy as the risk of others risks. As such, it need in new cognitive framework. In this case we study how manage complexity item. Methodology. Comparative analysis of models of reputation risk management devoted the cognitive framework located in time and institutional space. Key findings.Reputational risk management is reduction of internal cost of partic- ular activity, cover transactional cost of monitoring such type of risk and calculate external cost of reputation lost. One of this external cost is crush of reputation on public trust institutions. The current paper demonstrates and reviews different theoretical perspectives that conceptualize reputational risk management. The first part presents cognitive perspective on reputation. The second part covers behavioral approach to risk management. Finally, the paper provides practitioners with a systematic review of different approaches adopted to study reputational risk management. Keywords: reputational risk, moral hazard, cognitive framework. JEL Codes: A14, H12, P50 INTRODUCTION The reputational risk is placed at the top of the risk hierarchy as the risk of other risks.