Non-Conscripted Masculinities in 1940S British Narrative Cinema The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Gabriela Gogelová The Home Guard and the French Resistance in Situation Comedies by David Croft Bachelor‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph. D. 2015 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………… Author‟s signature I would like to thank my supervisor, Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D., for his professional advice, encouragement and patience. Table of Contents General Introduction 5 Chapter I: Situation Comedy and the BBC 8 Chapter II: Analysis of Dad’s Army 12 Description of the Characters 12 The British Home Guard vs. Croft and Perry‟s Dad’s Army 25 Chapter III: Analysis of ‘Allo ‘Allo! 30 Description of the Characters 30 The French Resistance vs. Croft and Lloyd‟s ‘Allo ‘Allo! 41 Conclusion 46 Works Cited 52 English Resume 55 Czech Resume 56 General Introduction The Second World War was undoubtedly the most terrible conflict of the twentieth century and one of the most destructive wars in history. It may therefore seem surprising that comedy writer David Croft chose exactly this period as a background for his most successful situation comedies. However, the huge success of the series Dad’s Army and ‘Allo ‘Allo! suggests that he managed to create sitcoms that are entertaining for wide audience and not offensive despite their connection to the Second World War. This thesis focuses on two of David Croft‟s sitcoms, Dad’s Army and ‘Allo ‘Allo!. The firstly mentioned sitcom was created in cooperation with Jimmy Perry and ran on BBC1 almost ten years from 1968 to 1977. -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

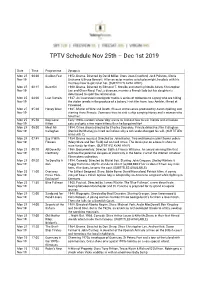

TPTV Schedule Nov 25Th – Dec 1St 2019

TPTV Schedule Nov 25th – Dec 1st 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 25 00:00 Sudden Fear 1952. Drama. Directed by David Miller. Stars Joan Crawford, Jack Palance, Gloria Nov 19 Grahame & Bruce Bennett. After an actor marries a rich playwright, he plots with his mistress how to get rid of her. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 02:15 Beat Girl 1960. Drama. Directed by Edmond T. Greville and starring Noelle Adam, Christopher Nov 19 Lee and Oliver Reed. Paul, a divorcee, marries a French lady but his daughter is determined to spoil the relationship. Mon 25 04:00 Last Curtain 1937. An insurance investigator tracks a series of robberies to a gang who are hiding Nov 19 the stolen jewels in the produce of a bakery. First film from Joss Ambler, filmed at Pinewood. Mon 25 05:20 Honey West 1965. Matter of Wife and Death. Classic crime series produced by Aaron Spelling and Nov 19 starring Anne Francis. Someone tries to sink a ship carrying Honey and a woman who hired her. Mon 25 05:50 Dog Gone Early 1940s cartoon where 'dog' wants to find out how to win friends and influence Nov 19 Kitten cats and gets a few more kittens than he bargained for! Mon 25 06:00 Meet Mr 1954. Crime drama directed by Charles Saunders. Private detective Slim Callaghan Nov 19 Callaghan (Derrick De Marney) is hired to find out why a rich uncle changed his will. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 07:45 Say It With 1934. Drama musical. Directed by John Baxter. Two well-loved market flower sellers Nov 19 Flowers (Mary Clare and Ben Field) fall on hard times. -

HANCOCK's HALF HOUR COLLECTIBLES Notes To

HANCOCK’S HALF HOUR COLLECTIBLES Notes to Accompany Volume 3 All photographs copyright (C) BBC (unless otherwise stated) The Tony Hancock Appreciation Society is delighted to have given its support to the production of this new and unique series concerning the lost works of Tony Hancock. Tony Hancock: BBC Publicity Shot for Hancock’s Half Hour, November 1956 The Tony Hancock Appreciation Society (THAS) Since its creation in 1976, the THAS has dedicated itself to preserving and promoting the works of Tony Hancock and, more crucially, to finding his broadcasts that were missing from the archives. Over the decades, these efforts have yielded a wealth of material, most notably lost episodes of his most beloved work on Hancock’s Half Hour for both television and radio. Many of these have now been located and returned to the BBC; some feature in this special series of Collectibles, now into 1 its third volume. However, many still remain lost at this time. In addition, our efforts have found other material – shows recorded before Hancock became a household name – from series such as Calling All Forces, Variety Bandbox and Star Bill. Again, examples of these can be found in this series. In the previous volumes, there was an extensive analysis of missing recordings from Hancock’s radio career, and, as ever, we remain hopeful that some of these recordings will emerge from private collections or, perhaps, the archives of the BBC or other institutions. In these notes, we will focus on a number of missing recordings and shows outside the ‘core’ work Hancock did on his eponymous series and those that preceded it. -

Lifeboats •Loval National Lilebodl Institution \ E Win Enea Mu Wings •^-^ «-^ Let This Uplifting Melody Inspire You

For everyone who helps save lives at sea Summer 2002 va National Lifeboat Ins' r 1 I Her Majesty opeffg her Gokteajybjjge celebrations with a visit to name the new lifeboat at Falmouth Lifeboats •loval National Lilebodl Institution \ e win enea mu wings •^-^ «-^ Let this uplifting melody inspire you Inscribed inside the lid is a message that lasts a lifetime for a daughter Sculptural porcelain butterfly with shimmering gold mother accents graces the lid sister friend Six Sparkling Swarovski crystals gratiddaugh ter grandmother 22-carat gold bands, 22-carat gold-finished feet and delicate golden \ heading REMARKABLE VALUE AT JUST £24.95 (+p&p) 7^ Actual size approximate!]! 3W inches wide created from the delicate watercolour-on-silk paintings of Lena Liu 080065U999 mile Rrlcrcnic. 178643 t takes an artist of rare talent and insight to capture the beauty PRIORITY RESERVATION FORM Iand grace of butterflies as well as a sense of the freedom they "Flights of Fancy" inspire. Now, the supremely gifted artist Lena Liu achieves both in Limit: one ul cat.li mu*k l><>\ pi i mlk-uor her "Flights of Fancy"music box, available exclusively through Bradford Editions. To: Bradford Editions, PO Box 653, Stoke-on-Trent ST4 4RA "Flights of Fancy" enchants the eye with its graceful fluted shape Please enter my reservation tor the "Flights of Fancy" music and Lena Liu's delicate watercolour artwork, depicting ivory box by Lena Liu. I understand that I NEED SEND NO dogwood blossoms and garnet-hued raspberries, surrounding two MONEY NOW. Please invoice me for £24.95 (plus £2.99 spectacular Red-spotted Purple butterflies. -

The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan Hughes, University of Central Lancashire The North of England is a place-myth as much as a material reality. Conceptually it exists as the location where the economic, political, sociological, as well as climatological and geomorphological, phenomena particular to the region are reified into a set of socio-cultural qualities that serve to define it as different to conceptualisations of England and ‘Englishness’. Whilst the abstract nature of such a construction means that the geographical boundaries of the North are implicitly ill-defined, for ease of reference, and to maintain objectivity in defining individual texts as Northern films, this paper will adhere to the notion of a ‘seven county North’ (i.e. the pre-1974 counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, Northumberland, County Durham, Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Cheshire) that is increasingly being used as the geographical template for the North of England within social and cultural history.1 The British film industry in 1941 As 1940 drew to a close in Britain any memories of the phoney war of the spring of that year were likely to seem but distant recollections of a bygone age long dispersed by the brutal realities of the conflict. Outside of the immediate theatres of conflict the domestic industries that had catered for the demands of an increasingly affluent and consuming population were orientated towards the needs of a war economy as plant, machinery, and labour shifted into war production. -

St Catharine's College Society Magazine 1

CONTENTS Sir Terence English 1 Honours and Awards 2 Editorial 3 The Master Elect, Professor David Ingram; University Appointments 4 Governing Body 5 Cheering up Depressed Mussels. Dr David Aldridge 8 Publications 9 Reviews and Notes 10 The College Staff 15 Dr Robert Evans' 90th Birthday Celebration; St Catharine's Gild 16 St Catharine of Alexandria 17 Arctic Circle Ski Race. Hugh Pritchard 18 College Society Reports 21 The St Catharine's Society: The President Elect and Officers of the Society 25 The St Catharine's Society: The AGM 1999 26 The St Catharine's Society: Mr Tom Cook (Honorary Secretary Retired): Presentation 27 The St Catharine's Society: The AGM 2000 Agenda and Sports Fund 28 The St Catharine's Society: Accounts 29 Weddings Births and Deaths 30 Obituaries 37 Matriculations 1999-2000 40 Postgraduates Registered and PhDs Approved 1999-2000 42 Appointments and Notes 44 M.C.R. and J.C.R 48 The Matterhorn Disaster. A. J. Longford 49 Kittens, Cardinals, and Alley cats. Professor Donald Broom 51 Gifts and Bequests; American & Canadian Friends 52 The College Chapel and Choir 53 The Singing Cats. Paul Griffin 54 The St Catharine's Society: Branch News 55 Down to the Sea in Ships. Captain Charles Styles R.N 56 College Club Reports 58 The University Cross Channel Race 2000 64 Blues 1999-2000 65 An Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race 1950 66 Awards and Prizes 68 Dr Paul Raithby and Chemists 72 Honorary Fellowships: Mr Jeremy Paxman and Professor Jonathan Bate 73 The Editor's Desk 74 Development Campaign 76 Annual Dinners: The Society; The Governing Body Invitation 80 Important Notes and Dates for All Readers 81 Cover: As we step into the new millennium College Main Court on Saturday 17th June 2000. -

Radio Times, January 24, 1947

Radio Times {lncorporaling World·J(adiol January 24,-1947, BBC PROGRAMMES __ FOR Vol.. 94, No •. 1217. Registered at the ~.P.O. as a Newspaper WELSH EDITION Jan. 26 Feb. I TWOPENCE JOURNAL OF --- TH E SSC P RI C E Home Service ESSEX contributes Sunday's 'Country Magazine' 'CENWCH 1M' YR HEN GANIADAU' A programme of old Welsh songs on Sunday evening HENRY HALL'S GUEST NIGHT from the Finsbury Park Empire, London, on Tuesday 'JOHNNY NOBLE' Story of an East-Coast fisherman Radio version of a 'Theatre Workshop' production: Thursday GERAINT GOODWIN -A portrait of the Welsh novelist by T. Rowland Hughes on Friday 'OTHER PEOPLE'S LIVES' A. A. Milne's play in Saturday Night Theatre ~ Light Programme DICK BARTON'S ADVENTURES Every weeknight at 6.45 : omnibus edition on Saturday at 11.0 a.m. 'IGNORANCE IS BLISS' 'The limit-of human stupidity' on Monday evening- "SENSATION' _The suffragette who threw herself in front of the King's horse: Tuesday THE ROYAL TOUR. Their Majestif!S the King and Queen,. accompanied by the two WILFRED PICKLES Princesses, sail for Cape ToWn on Saturday, February I, to begin a nine-weeks' tour of the The' Have a Go !' quiz visits Ayr ynion of South Africa and Rhodesia. It will be the first visit of Their Majesties to South Africa on Wednesday , 'MUCH-BINDING-IN-THE-MARSH' T every stage"of the tour listeners at home will HE Fourth Test Match begins at Adelaide on Thursday and Sunday (Friday; Home) A be kept in touch with the Royal progress T Friday, and as Adelaide is much farther west through the reports of BBC commentators and than Melbourne, play 'starts half-an~hour later than FOURTH TEST MATCH observers. -

MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian

#10 silent comedy, slapstick, music hall. CONTENTS 3 DVD news 4Lost STAN LAUREL footage resurfaces 5 Comedy classes with Britain’s greatest screen co- median, WILL HAY 15 Sennett’s comedienne MARJORIE BEEBE—Ian 19 Did STAN LAUREL & LUPINO LANE almost form a team? 20 Revelations and rarities : LAUREL & HARDY, RAYMOND GRIFFITH, WALTER FORDE & more make appearances at Kennington Bioscope’s SILENT LAUGHTER SATURDAY 25The final part of our examination of CHARLEY CHASE’s career with a look at his films from 1934-40 31 SCREENING NOTES/DVD reviews: Exploring British Comedies of the 1930s . MORE ‘ACCIDENTALLY CRITERION PRESERVED’ GEMS COLLECTION MAKES UK DEBUT Ben Model’s Undercrank productions continues to be a wonderful source of rare silent comedies. Ben has two new DVDs, one out now and another due WITH HAROLD for Autumn release. ‘FOUND AT MOSTLY LOST’, presents a selection of pre- LLOYD viously lost films identified at the ‘Mostly Lost’ event at the Library of Con- gress. Amongst the most interesting are Snub Pollard’s ‘15 MINUTES’ , The celebrated Criterion Collec- George Ovey in ‘JERRY’S PERFECT DAY’, Jimmie Adams in ‘GRIEF’, Monty tion BluRays have begun being Banks in ‘IN AND OUT’ and Hank Mann in ‘THE NICKEL SNATCHER’/ ‘FOUND released in the UK, starting AT MOSTLY LOST is available now; more information is at with Harold Lloyd’s ‘SPEEDY’. www.undercrankproductions.com Extra features include a com- mentary, plus documentaries The 4th volume of the ‘ACCIDENTALLY PRESERVED’ series, showcasing on Lloyd’s making of the film ‘orphaned’ films, many of which only survive in a single print, is due soon. -

Dads Army: Complete Radio Series Two Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DADS ARMY: COMPLETE RADIO SERIES TWO PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jimmy Perry,David Croft,Arthur Lowe,John Le Mesurier,Full Cast | 1 pages | 14 Dec 2016 | BBC Audio, A Division Of Random House | 9781471366604 | English | London, United Kingdom Dads Army: Complete Radio Series Two PDF Book Mainwaring teaches the men to use the public telephone system as emergency communication. I love it. Audio Software icon An illustration of a 3. Episode list Missing episodes Radio episodes. Some actors can end up feeling resentful when a role comes to define them, but Lavender has no such reservations. Private Pike's mother agrees to take in a child evacuee, but Wilson misunderstands her and believes she is pregnant. By the third episode, screened on 14 August, the critics were catching up with public enthusiasm. They seem unlikely to win and their chances worsen when Jones has a bout of malaria. Cancel Save. Frazer's increasingly dictatorial manner soon alienates the platoon. Mainwaring is charged with showing a light and taken to court by a gleeful Hodges. Swallow's Bank takes a direct hit during an air-raid, but the bomb fails to explode, leaving Mainwaring and Wilson stuck in the vault with it. The Day the Balloon Went Up. Mainwaring spots an unexploded bomb caught in the wires. Namespaces Article Talk. One section, though, mistakes the other for the enemy. Ten Seconds From Now. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. After Frazer moans about Mainwaring wasting his time with irrelevant lectures, he allows Frazer become Captain for a couple of days - but the power goes to his head. -

Fred Tomlin (Boom Operator) 1908 - ? by Admin — Last Modified Jul 27, 2008 02:45 PM

Fred Tomlin (boom operator) 1908 - ? by admin — last modified Jul 27, 2008 02:45 PM BIOGRAPHY: Fred Tomlin was born in 1908 in Hoxton, London, just around the corner from what became the Gainsborough Film Studios (Islington) in Poole Street. He first visited the studio as a child during the filming of Woman to Woman (1923). He entered the film industry as an electrician, working in a variety of studios including Wembley, Cricklewood and Islington. At Shepherd’s Bush studio he got his first experience as a boom operator, on I Was A Spy (1933). Tomlin claims that from that point until his retirement he was never out of work, but also that he was never under permanent contract to any studio, working instead on a freelance basis. During the 1930s he worked largely for Gaumont and Gainsborough on films such as The Constant Nymph (1933), Jew Suss (1934), My Old Dutch (1934), and on the Will Hay comedies, including Oh, Mr Porter (1937) and Windbag the Sailor (1936). During the war, Tomlin served in the army, and on his return continued to work as a boom operator on films and television (often alongside Leslie Hammond) until the mid 1970s. His credits include several films for Joseph Losey (on Boom (1968) and Secret Ceremony (1968)) and The Sea Gull (1968)for Sidney Lumet, as well as TV series such as Robin Hood and The Buccaneers and a documentary made in Cuba for Granada TV. SUMMARY: In this interview from 1990, Tomlin talks to Bob Allen about his career, concentrating mainly on the pre-war period. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter.