HANCOCK's HALF HOUR COLLECTIBLES Notes To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TV Preview: Tales of Television Centre at BFI Southbank / Tue 15 May / 18:10

PRESS RELEASE April 2012 12/29 TV Preview: Tales of Television Centre At BFI Southbank / Tue 15 May / 18:10 BFI Southbank is delighted to present a preview screening of Tales of Television Centre, the upcoming feature-length documentary telling the story of one of Britain’s most iconic buildings as the BBC prepares to leave it. The screening will be introduced by the programme’s producer-director Richard Marson The story is told by both staff and stars, among them Sir David Frost, Sir David Attenborough, Dame Joan Bakewell, Jeremy Paxman, Sir Terry Wogan, Esther Rantzen, Angela Rippon, Biddy Baxter, Edward Barnes, Sarah Greene, Waris Hussein, Judith Hann, Maggie Philbin, John Craven, Zoe and Johnny Ball and much loved faces from Pan’s People (Babs, Dee Dee and Ruth) and Dr Who (Katy Manning, Louise Jameson and Janet Fielding). As well as a wealth of anecdotes and revelations, there is a rich variety of memorable, rarely seen (and in some cases newly recovered) archive material, including moments from studio recordings of classic programmes like Vanity Fair, Till Death Us Do Part, Top of the Pops and Dr Who, plus a host of vintage behind-the-scenes footage offering a compelling glimpse into this wonderful and eccentric studio complex – home to so many of the most celebrated programmes in British TV history. Press Contacts: BFI Southbank: Caroline Jones Tel: 020 7957 8986 or email: [email protected] Lucy Aronica Tel: 020 7957 4833 or email: [email protected] NOTES TO EDITORS TV Preview: Tales of Television Centre Introduced by producer-director Richard Marson BBC 2012. -

Imperial Desire and Masculine Crisis in Early Francoist Film Representations of the Loss of the Philippines and Cuba

IMPERIAL DESIRE AND MASCULINE CRISIS IN EARLY FRANCOIST FILM REPRESENTATIONS OF THE LOSS OF THE PHILIPPINES AND CUBA Jo Labanyi New York University It is well known that one of the prime motives triggering the Nationalist uprising against the Second Republic in 1936 was military resentment at the loss of empire, perceived by the military as the fault of inept politicians to whose orders they were subordinate. As is also well known, the 1941 film scripted by General Franco, Raza , starts in 1898 with the return of its naval-captain patriarch, Churruca, from service in the Philippines, only to be despatched immediately to Cuba, dying in battle against the US fleet. Churruca complains that the Spanish government’s ‘neglect’ of the Philippines is aggravating insurrection. The Spanish naval commander in Cuba, as he sends his captains into battle against the US fleet, tells them they are going to certain defeat but have to obey government orders. In Raza , this discourse on empire is intimately bound up with a discourse on patriarchy; past military defeats are compensated, not just by the Nationalist victory parade of April 1939 which ends the film, but by the docility with which, throughout the movie, women accept their role of “service” to men. The obverse of this is that male heroism depends on women continuing to play this instrumental role: a dependence on women that is the source of male unease. The two films discussed in this article -Los últimos de Filipinas and Bambú , both made in 1945 and set against the independence struggle in the Philippines and Cuba respectively- oscillate between stress on male bonding, which excludes women, and the dramatization of women’s power over men. -

Breathtaking Stories of Extreme Filming. Read the Full Story on Page 6

The newspaper for BBC pensioners - with highlights from Ariel Heights, Camera, Action Breathtaking stories of extreme filming. Read the full story on page 6. June 2011 • Issue 4 Yes, Prime Lord Patten Minister back takes the helm Sounds better? on stage Page 2 Page 7 Page 12 NEWS • LifE aftEr auNtiE • CLaSSifiEdS • Your LEttErS • obituariES • CroSPEro 02 uPdatE froM thE bbC Patten takes helm at BBC Trust On 3 May, Lord Patten began his appointment as chairman of the BBC Trust – with an interesting first day spent taking questions from staff in a ringmain session. Quality First) should be all about and I hope we’ll be able to discuss options with the Executive during the summer.’ 2011 pay offer It is also apparent that the new chairman is ready and willing to deal with the – an update repercussions of the less popular decisions to be taken, and those which will not always Further to requests by the unions for all be accepted gladly by the licence fee payer. staff in bands 2-11 to be awarded a pay ‘I hope we won’t be talking about closing increase which is ‘substantially above services but, whatever we are talking about inflation’, the BBC has offered a 2% doing, if the Trust and the Executive are increase – which falls far short of the agreed it is the best way of using the money Retail Prices Index (RPI) figures on which then we have to stand by the consequences. If it is intended to be based (5.2% as at that involves answering thousands of emails, April 2011). -

1 BBC Four Biopics

BBC Four biopics: Lessons in Trashy Respectability The broadcast of Burton and Taylor in July 2013 marked the end of a decade- long cycle of feature-length biographical dramas transmitted on BBC Four, the niche arts and culture digital channel of the public service broadcaster. The subjects treated in these biopics were various: political figures, famous cooks, authors of popular literature, comedians and singers. The dramas focused largely on the unhappy or complex personal lives of well-loved figures of British popular culture. From the lens of the 21st century, these dramas offered an opportunity for audiences to reflect on the culture and society of the 20th century, changing television’s famous function of ‘witness’ to one of ‘having witnessed’ and/or ‘remembering’ (Ellis, 2000). The programmes function as nostalgia pieces, revisiting personalities familiar to the anticipated older audience of BBC Four, working in concert with much of the archive and factual content on the digital broadcaster’s schedules. However, by revealing apparent ‘truths’ that reconfigure the public images of the figures they narrate, these programmes also undermine nostalgic impulses, presenting conflicting interpretations of the recent past. They might equally be seen as impudent incursions onto the memory of the public figures, unnecessarily exposing the real-life subjects to censure, ridicule or ex post facto critical judgement. Made thriftily on small budgets, the films were modest and spare in visual style but were generally well received critically, usually thanks to writerly screenplays and strong central performances. The dramas became an irregular but important staple of the BBC Four schedule, furnishing the channel with some of their highest ratings in a history chequered by low audience numbers. -

HATTIE JACQUES Born Josephine Edwina Jacques on February 7" 1922 She Went on to Become a Nationally Recognised Figure in the British Cinema of the 1950S and 60S

Hattie Jacaues Born 127 High St 1922 Chapter Twelve HATTIE JACQUES Born Josephine Edwina Jacques on February 7" 1922 she went on to become a nationally recognised figure in the British cinema of the 1950s and 60s. Her father, Robin Jacques was in the army and stationed at Shorncliffe Camp at the time of her birth. The Register of Electors shows the Jacques family residing at a house called Channel View in Sunnyside Road. (The register shows the name spelled as JAQUES, without the C. Whether Hattie changed the spelling or whether it was an error on the part of those who printed the register I don’t know) Hattie, as she was known, made her entrance into the world in the pleasant seaside village of Sandgate, mid way between Folkestone to the east and Hythe to the west. Initially Hattie trained as a hairdresser but as with many people of her generation the war caused her life to take a different course. Mandatory work saw Hattie first undertaking nursing duties and then working in North London as a welder Even in her twenties she was of a generous size and maybe as defence she honed her sense of humour after finding she had a talent for making people laugh. She first became involved in show business through her brother who had a job as the lift operator at the premises of the Little Theatre located then on the top floor of 43 Kings Street in Covent Garden. At end of the war the Little Theatre found itself in new premises under the railway arches below Charing Cross Station. -

'Pinkoes Traitors'

‘PINKOES AND TRAITORS’ The BBC and the nation, 1974–1987 JEAN SEATON PROFILE BOOKS First published in Great Britain in !#$% by Pro&le Books Ltd ' Holford Yard Bevin Way London ()$* +,- www.pro lebooks.com Copyright © Jean Seaton !#$% The right of Jean Seaton to be identi&ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act $++/. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN +4/ $ /566/ 545 6 eISBN +4/ $ /546% +$6 ' All reasonable e7orts have been made to obtain copyright permissions where required. Any omissions and errors of attribution are unintentional and will, if noti&ed in writing to the publisher, be corrected in future printings. Text design by [email protected] Typeset in Dante by MacGuru Ltd [email protected] Printed and bound in Britain by Clays, Bungay, Su7olk The paper this book is printed on is certi&ed by the © $++6 Forest Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-!#6$ CONTENTS List of illustrations ix Timeline xvi Introduction $ " Mrs Thatcher and the BBC: the Conservative Athene $5 -

Brass Bands of the World a Historical Directory

Brass Bands of the World a historical directory Kurow Haka Brass Band, New Zealand, 1901 Gavin Holman January 2019 Introduction Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 6 Angola................................................................................................................................ 12 Australia – Australian Capital Territory ......................................................................... 13 Australia – New South Wales .......................................................................................... 14 Australia – Northern Territory ....................................................................................... 42 Australia – Queensland ................................................................................................... 43 Australia – South Australia ............................................................................................. 58 Australia – Tasmania ....................................................................................................... 68 Australia – Victoria .......................................................................................................... 73 Australia – Western Australia ....................................................................................... 101 Australia – other ............................................................................................................. 105 Austria ............................................................................................................................ -

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany Including Recent Acquisitions, Manuscripts & Letters, Presentation & Association Copies, Art & Illustrated Works, Film-Related Material, Etcetera. Catalogue 349 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.williamreesecompany.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are consid- ered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inven- tory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. -

HANCOCK's HALF HOUR COLLECTIBLES Notes To

HANCOCK’S HALF HOUR COLLECTIBLES Notes to accompany Volume 2 All photographs copyright (C) BBC The Tony Hancock Appreciation Society is delighted to have given its support to the production of this new and unique series concerning the lost or rare work of, and related to, Tony Hancock, one of our greatest comedians. Tony Hancock,1951 The Tony Hancock Appreciation Society (THAS) Since its inception in 1976, the THAS and its many allies have been at the forefront of efforts to find, preserve and promote the works of Tony Hancock. As detailed in the previous volume of this series, this toil has, over the decades, yielded innumerable discoveries of work by Hancock that was previously believed to have been lost. The result is that the THAS now has the most extensive archive of Hancock’s stage, radio, television, and film work in the world. In addition, we have myriad recorded items related to his career, such as interviews and documentaries featuring Hancock, his colleagues and friends. Each offers valuable insights into his life and work. It is this extensive collection, combined principally with that of Ted Kendall, the noted sound engineer and media researcher, and the contents of the BBC Sound Archives, that have enabled the publication of Hancock’s Half Hour Collectibles. It is natural for modern audiences to question why broadcast material is missing from the period in which Hancock was ascendant from the late 40s until 1968. As many readers may know, this issue has, in fact, affected the legacy of numerous performers, programmes and broadcasts; and this phenomenon is by no means limited to the BBC, the United Kingdom, or indeed, the period during which Hancock was active. -

The Nation's Matron: Hattie Jacques and British Post-War Popular Culture

The Nation’s Matron: Hattie Jacques and British post-war popular culture Estella Tincknell Abstract: Hattie Jacques was a key figure in British post-war popular cinema and culture, condensing a range of contradictions around power, desire, femininity and class through her performances as a comedienne, primarily in the Carry On series of films between 1958 and 1973. Her recurrent casting as ‘Matron’ in five of the hospital-set films in the series has fixed Jacques within the British popular imagination as an archetypal figure. The contested discourses around nursing and the centrality of the NHS to British post-war politics, culture and identity, are explored here in relation to Jacques’s complex star meanings as a ‘fat woman’, ‘spinster’ and authority figure within British popular comedy broadly and the Carry On films specifically. The article argues that Jacques’s star meanings have contributed to nostalgia for a supposedly more equitable society symbolised by socialised medicine and the feminine authority of the matron. Keywords: Hattie Jacques; Matron; Carry On films; ITMA; Hancock’s Half Hour; Sykes; star persona; post-war British cinema; British popular culture; transgression; carnivalesque; comedy; femininity; nursing; class; spinster. 1 Hattie Jacques (1922 – 1980) was a gifted comedienne and actor who is now largely remembered for her roles as an overweight, strict and often lovelorn ‘battle-axe’ in the British Carry On series of low- budget comedy films between 1958 and 1973. A key figure in British post-war popular cinema and culture, Hattie Jacques’s star meanings are condensed around the contradictions she articulated between power, desire, femininity and class. -

Loo* Ocr for Voyr Pockets.The Approaching Anniversaries

' ggs=. -JJ'J The t'ttlvrnnl I »nkc«' Nation. Mu-rlnl, Sailed from BtUtol May J, North Indian Ocean. Auction baic»* NEW Solid a 11 k America, (ttf- WK WERE WRONG IN MAYING THE On ei N S! i i J i I i> 0 S T S C R I P T7 INORAHAM, written Wedueoday cuing. ith nu(., by the llev. Henry l»l< te for the ITrifie. Romance by PIIOKEHSOR W. Fellows, Mr. Grose» il. Km.liiii of ti Arrived at Kail River TV THOMAH HEM MBM». " wouUl this » i*i, but it h Philadelphia. Mav ?, Lionida*, Atlantic 0« o>» For our umi U Soulhem Cart et/uttu/eaor, for the Nation," oppcur Miss IUhkii.t lints, of Stone, of tlii> bbla i|H m. [Stores Not. 21 Jim and 116 Fulton strett.) !>H LAHONK.t'S LECTURES. i£i- daughter " c\pressly A'aph - this morning's Mail, tee fourth o cotnu out in tlic next number. City. A uli-1..U' jv» >i»d up Narin-; I Till nsf)At' \ NINO. MAI :tb? pope. _ l<i/ keemug however, containing no B.yM.yJ, _ FTUDAY? fil l I. The present one i* in go**! On Itli the liev. Ileitis lie.t.d Coin, <lat«prnbr.ldy in FiK./eieu Coffin, Nam. Ai o'clock. in ili»? ties room, an of the sheets. The Wednesday afternoon, inst., by 300 bbt#. Ill's THR r.AKTil. the richest mutter of y large (. ha*e, I'lUiLi 1 !>. Tili.' r, of this to Miss I'Mtm. Piano ForUa, Organ-. -

Spring 2006 Bulletin 85

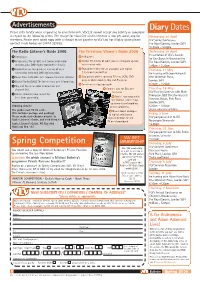

Advertisements Diary Dates Please refer to VLV when responding to advertisements. VLV Ltd cannot accept any liability or complaint in regard to the following offers. The charge for classified advertisements is 30p per word, 20p for Wednesday 26 April members. Please send typed copy with a cheque made payable to VLV Ltd. For display space please VLV Spring Conference contact Linda Forbes on 01474 352835. The Royal Society, London SW1 10.30am – 5.00pm The Radio Listener's Guide 2006 The Television Viewer's Guide 2006 Wednesday 26 April Presentation of VLV’s Awards G 160 pages G 160 pages for Excellence In Broadcasting G Frequencies for all BBC and commercial radio G Digital TV details of what you need to pick up Sky, The Royal Society, London SW1 stations, plus DAB digital transmitter details. Freeview or cable 1.45pm – 2.30pm G Radio Reviews Independent reviews of over G Transmitter sites for all analogue and digital Thursday, 11 May 130 radios including DAB digital radios. television transmitters. An Evening with Joan Bakewell G News from both BBC and commercial radio stations. G Equipment advice covering TV sets, VCRs, DVD One Whitehall Place, players and recorders, Sky and Freeview. G Digital Radio (DAB) The latest news and information. London SW1 G Freeview set-top box guide. 6.30pm – 8.20pm G Sky and Freeview radio information and G channel lists. Channel lists for Sky and Thursday, 18 May Freeview. VLV Evening Seminar with Mark G Advice showing how to get the G Thompson, BBC Director General best from your radio.