The Manuscripts of Jan Van Naaldwijk's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Visual Culture

Picturing Processions: The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-century Dutch Visual Culture By © 2017 Megan C. Blocksom Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Linda Stone-Ferrier Dr. Marni Kessler Dr. Anne D. Hedeman Dr. Stephen Goddard Dr. Diane Fourny Date Defended: November 17, 2017 ii The dissertation committee for Megan C. Blocksom certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Picturing Processions: The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-century Dutch Visual Culture Chair: Dr. Linda Stone-Ferrier Date Approved: November 17, 2017 iii Abstract This study examines representations of religious and secular processions produced in the seventeenth-century Northern Netherlands. Scholars have long regarded representations of early modern processions as valuable sources of knowledge about the rich traditions of European festival culture and urban ceremony. While the literature on this topic is immense, images of processions produced in the seventeenth-century Northern Netherlands have received comparatively limited scholarly analysis. One of the reasons for this gap in the literature has to do with the prevailing perception that Dutch processions, particularly those of a religious nature, ceased to be meaningful following the adoption of Calvinism and the rise of secular authorities. This dissertation seeks to revise this misconception through a series of case studies that collectively represent the diverse and varied roles performed by processional images and the broad range of contexts in which they appeared. Chapter 1 examines Adriaen van Nieulandt’s large-scale painting of a leper procession, which initially had limited viewership in a board room of the Amsterdam Leprozenhuis, but ultimately reached a wide audience through the international dissemination of reproductions in multiple histories of the city. -

Neo-Latin News

44 SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NEWS NEO-LATIN NEWS Vol. 61, Nos. 1 & 2. Jointly with SCN. NLN is the official publica- tion of the American Association for Neo-Latin Studies. Edited by Craig Kallendorf, Texas A&M University; Western European Editor: Gilbert Tournoy, Leuven; Eastern European Editors: Jerzy Axer, Barbara Milewska-Wazbinska, and Katarzyna To- maszuk, Centre for Studies in the Classical Tradition in Poland and East-Central Europe, University of Warsaw. Founding Editors: James R. Naiden, Southern Oregon University, and J. Max Patrick, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and Graduate School, New York University. ♦ Petrarch and St. Augustine: Classical Scholarship, Christian Theol- ogy and the Origins of the Renaissance in Italy. By Alexander Lee. Brill’s Studies in Intellectual History, 210. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2012. x + 382 pp. $177. Petrarch’s opera is extensive, that of Augustine is extraordinarily vast, and the literature on both is vaster still. To bridge them successfully is a significant undertaking. Over the past fifty years, scholars have attempted this task, from classic studies by Charles Trinkaus (often discussed here) to more recent ones such as C. Quillen’s Rereading the Renaissance: Petrarch, Augustine and the Language of Humanism (1995) and M. Gill’s Augustine in the Italian Renaissance: Art and Philosophy from Petrarch to Michelangelo (2005). In a new study, Alexander Lee argues that “Petrarch’s thought on moral questions was derived principally from the writings of St. Augustine” (24). Lee contends that Petrarch, rather than being philosophically inconsistent as is often suggested, was especially influenced by Augustine’s early works, most notably the Soliloquies and the De vera religione, which provided him with an interpretive method for incorporating classical literature and philosophy into Christian moral theology. -

The Humanist Discourse in the Northern Netherlands

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth-century academic Leiden Kromhout, D. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kromhout, D. (2016). Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth- century academic Leiden. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Chapter 1: The humanist discourse in the Northern Netherlands This chapter will characterize the discourse of the Leiden humanists in the first decade of the seventeenth century. This discourse was in many aspects identical to the discourse of the Republic of Letters. The first section will show how this humanist discourse found its place at Leiden University through the hands of Janus Dousa and others. -

Introduction

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth-century academic Leiden Kromhout, D. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kromhout, D. (2016). Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth- century academic Leiden. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Introduction Ill. 1: Pageant at the inauguration of Leiden University, Anonymous (1575) The inauguration of Leiden University on 8 February 1575 was a moment of great importance in the process of growing self-awareness in the Northern Netherlands. After a troublesome start, the Revolt was finally gaining momentum. It has often been debated whether the Dutch Revolt was a matter of money, government, or religion.2 The fact is that both nobility and the ruling class and a substantial proportion of the common people were not content with Philip II’s measures pertaining to all these areas. -

The Roots of Nationalism

HERITAGE AND MEMORY STUDIES 1 HERITAGE AND MEMORY STUDIES Did nations and nation states exist in the early modern period? In the Jensen (ed.) field of nationalism studies, this question has created a rift between the so-called ‘modernists’, who regard the nation as a quintessentially modern political phenomenon, and the ‘traditionalists’, who believe that nations already began to take shape before the advent of modernity. While the modernist paradigm has been dominant, it has been challenged in recent years by a growing number of case studies that situate the origins of nationalism and nationhood in earlier times. Furthermore, scholars from various disciplines, including anthropology, political history and literary studies, have tried to move beyond this historiographical dichotomy by introducing new approaches. The Roots of Nationalism: National Identity Formation in Early Modern Europe, 1600-1815 challenges current international scholarly views on the formation of national identities, by offering a wide range of contributions which deal with early modern national identity formation from various European perspectives – especially in its cultural manifestations. The Roots of Nationalism Lotte Jensen is Associate Professor of Dutch Literary History at Radboud University, Nijmegen. She has published widely on Dutch historical literature, cultural history and national identity. Edited by Lotte Jensen The Roots of Nationalism National Identity Formation in Early Modern Europe, 1600-1815 ISBN: 978-94-6298-107-2 AUP.nl 9 7 8 9 4 6 2 9 8 1 0 7 2 The Roots of Nationalism Heritage and Memory Studies This ground-breaking series examines the dynamics of heritage and memory from a transnational, interdisciplinary and integrated approaches. -

Illinois Classical Studies

27 Platons KuB und seine Folgen WALTHER LUDWIG "... when instantly Phoebe grew more composed, after two or three sighs, and heart-fetched Oh's! and giving me a kiss that seemed to exhale her soul through her lips, she replaced the bed-cloaths over us." John Cleland (1709-1789) laBt in seinen "Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure" (zucrst gedruckt London 1749) Fanny Hill diese Erinnerungen aussprechen.' Nur wenigen Lesem des popularen Romans wird aufgefallen sein, daB die Vorstellung der Seele, die wahrend eines Kusses durch die Lippen zum Partner uberzugehen scheint, natiirlich direkt oder indirekt auf ein beriihmtes, bis ins 20. Jahrhundert Platon zugeschriebcnes Epigramm zuruckgeht, vielleicht direkt, da John Clclands Bildung durchaus ausreichte, um dieses Epigramm in seiner griechischen Originalform oder in eincr seiner lateinischen Obersetzungen zu kennen (er hatte ab 1722 die humanistisch orientierte Westminster School in London besucht und schrieb 1755 das Drama "Titus Vespasian" uber den romischen Kaiser), und sicher indirekt, da das Motiv langst in die neulateinische und nationalsprachliche Liebesdichtung eingegangen war. Grundsatzlich ist das Motiv dort auch den Literaturwissenschafdem bekannt. Der Germanist H. Pyritz schrieb 1963 in seinem Buch uber den deutschen Lyriker Paul Fleming (1609-1640): "... lange fortwirkend in Flemings Dichtung ist ein . Motiv, das . zum eisemen Bestand der neulateinischen Poesie und aller ihrer volkssprachlichen Ableger gchort: der Gedanke von Scelenraub und Seelentausch im KuB."^ Jedoch ist Pyritz das Platon-Epigramm als Quelle unbekannt; er ziliert keine Belege fiir das Motiv vor dem Nicdcrlander Joannes Secundus (1511- 1536) und sieht anschcincnd in ihm seinen Urheber. Da die Literaturwissenschaftler der Gegenwart das Motiv, sofem sie es kennen, also zumindcst nicht immer als anlikes Motiv erkenncn und da insgesaml unbekannt zu sein scheint, auf welchem Weg dieses Motiv in die * S. -

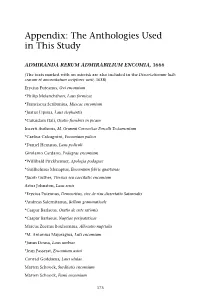

Appendix: the Anthologies Used in This Study

Appendix: The Anthologies Used in This Study ADMIRANDA RERUM ADMIRABILIUM ENCOMIA, 1666 (The texts marked with an asterisk are also included in the Dissertationum ludi- crarum et amoenitatum scriptores varii, 1638) Erycius Puteanus, Ovi encomium *Philip Melanchthon, Laus formicae *Franciscus Scribanius, Muscae encomium *Justus Lipsius, Laus elephantis *Cuiusdam Itali, Oratio funebris in picam Incerti Authoris, M. Grunnii Corocottae Porcelli Testamentum *Caelius Calcagnini, Encomium pulicis *Daniel Heinsius, Laus pediculi Girolamo Cardano, Podagrae encomium *Willibald Pirckheimer, Apologia podagrae *Guilhelmus Menapius, Encomium febris quartanae *Jacob Guther, Tiresias seu caecitatis encomium Artur Johnston, Laus senis *Erycius Puteanus, Democritus, sive de risu dissertatio Saturnalis *Andreas Salernitanus, Bellum grammaticale *Caspar Barlaeus, Oratio de ente rationis *Caspar Barlaeus, Nuptiae peripateticae Marcus Zuerius Boxhornius, Allocutio nuptialis *M. Antonius Majoragius, Luti encomium *Janus Dousa, Laus umbrae *Jean Passerat, Encomium asini Conrad Goddaeus, Laus ululae Marten Schoock, Surditatis encomium Marten Schoock, Fumi encomium 175 176 Appendix Mantissa, Itali cujusdam Authoris, Oratio funebris in gallum Thessalae mulieris; Oratio funebris in felem Florae viduae; Oratio funebris in canem Leonteum CASPAR DORNAU, AMPHITHEATRUM SAPIENTIAE SOCRATICAE IOCO-SERIAE, Vol. 2, 1619 (Only the texts used in my study) Aulus Gellius, Noctes Atticae (17.12, Thersites et quartana) Ulrich von Hutten, Febris prima et secunda Gulielmus Menapius -

Thesis (Complete)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth-century academic Leiden Kromhout, D. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kromhout, D. (2016). Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth- century academic Leiden. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:25 Sep 2021 Clashes of Discourses Humanists and Calvinists in Seventeenth-Century Academic Leiden David Kromhout cover.indd 1 11-02-16 14:34 Clashes of Discourses Humanists and Calvinists in Seventeenth-Century Academic Leiden David Kromhout Clashes of Discourses Humanists and Calvinists in Seventeenth-Century Academic Leiden ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. -

Continuity and Rupture: Comparative Literature and the Latin Tradition

This is a repository copy of Continuity and Rupture: Comparative Literature and the Latin Tradition. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/162414/ Version: Accepted Version Article: White, P orcid.org/0000-0001-6200-5489 (2020) Continuity and Rupture: Comparative Literature and the Latin Tradition. Comparative Critical Studies, 17 (3). pp. 373-389. ISSN 1744-1854 https://doi.org/10.3366/ccs.2020.0370 © British Comparative Literature Association. This is an author produced version of an article published in Comparative Critical Studies. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Continuity and Rupture: Comparative Literature and the Latin Tradition1 PAUL WHITE In this contribution I aim to do two things: to start to think about potentially productive dialogues between the minimally theorized discipline of Neo-Latin studies and the (perhaps) excessively theoretically self-conscious discipline of Comparative Literature; and to make a case that the Latin tradition and Neo-Latin literature in particular should interest the comparatist because it exemplifies,– and engages with, some of the key– problems currently at issue in Comparative Literature. -

Neo-Latin News 149

NEO-LATIN NEWS 149 NEO-LATIN NEWS Vol. 50, Nos. 1 & 2. Jointly with SCN. Subscriptions: $15.00 ($20.00 international) for one year; $28.00 ($37.00) for two years; $40.00 ($52.00) for three years. Checks or money orders are payable to Seventeenth-Century News, 4227 TAMU, Col- lege Station, Texas 77843-4227. NLN is the official publica- tion of the American Association for Neo-Latin Studies. Edited by Craig Kallendorf, Texas A&M University; Western Eu- ropean Editor: Gilbert Tournoy, Leuven; Eastern European Edi- tors: Jerzy Axer, Barbara Milewska-Waïbi½ska, and Katarzyna Tomaszuk, Centre for Studies in the Classical Tradition in Poland and East-Central Europe, University of Warsaw. Founding Edi- tors: James R. Naiden, Southern Oregon University, and J. Max Patrick, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and Graduate School, New York University. The Latin Odes of Jean Dorat. Trans. by David Slavitt. Washington: Orchises, 2000. 94 pp. $20. David Slavitt is well known as a translator of the classics, especially of classical drama by Seneca, Aristophanes, Aeschylus, and Euripides, and as a poet and novelist. Given that classicists tend to ignore Latinity as late as that of the Renaissance, it is a pleasant surprise to discover that Slavitt has turned his attention to The Latin Odes of Jean Dorat, the verse of a French humanist, scholar, and poet. Dorat’s relative obscurity outside of Neo-Latin studies (itself considered a very arcane field in the United States) is aggravated by the fact that little of his work has survived. While we have doubtless lost much of the poetry that he wrote, a great deal of his production probably con- sisted of lessons delivered orally as a teacher: after all, Dorat was the French royal reader in Greek and the preceptor of several of the French Plèiade poets. -

An Examination of Grotius' Antiquity of the Batavian

NATIONHOOD AND CONSTITUTIONALISM IN THE DUTCH REPUBLIC: AN EXAMINATION OF GROTIUS’ ANTIQUITY OF THE BATAVIAN REPUBLIC Ethan Alexander-Davey1,2 Abstract: The emphasis in contemporary democratic theory and in the history of political thought on the ‘natural rights’ theory of popular sovereignty of Locke, precursors of which are found in the work of Hugo Grotius and others, obscures an important relationship between constitutional self-government and nationalism. Through an examination of the early political writings of Grotius, especially his Antiquity of the Batavian Republic, this essay shows how a national consciousness forged out of memories of native traditions of self-government, and stories of heroic ancestors who successfully defended those traditions against usurpers and tyrants, gives concrete substance to otherwise inchoate theories of constitutional self-government. Keywords: Hugo Grotius, the Dutch Republic, the Dutch Revolt, nationalism, nationhood, national identity, constitutionalism, the ancient constitution, mixed con- stitution, self-government, popular sovereignty, liberty. Introduction Nationalism has fallen into disrepute since the end of the Second World War. Motivated by the horrors perpetrated by the Nazi regime, Jürgen Habermas, while acknowledging the ‘umbilical links’ of modern democracy to national consciousness, has promoted the formation of post-national identities and tra- ditions for the grounding of constitutional self-government.3 John Rawls, too, turned to Kantian universals in his formulation of a liberal -

Introduction Montaigne and the Low Countries—Synopsis and New Perspectives

INTRODUCTION MONTAIGNE AND THE LOW COUNTRIES—SYNOPSIS AND NEW PERSPECTIVES Paul J. Smith Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) is known as the inventor of the essay, a successful genre, in which the author expresses in a free and personal style his ideas on a great diversity of subjects. Typical for Montaigne are his far-reaching relativism, his strong craving for self-knowledge and self-description and his taste for freedom and tolerance. Montaigne’s informal and often recalcitrant way of thinking and writing has had a longlasting in uence in Europe. Francis Bacon, Descartes, Pascal, Locke, Voltaire and Rousseau admired or detested him. Goethe and Nietzsche considered him one of the principal gures of European philosophy. For Claude Lévi-Strauss and Julia Kristeva Montaigne stands at the very basis of modern re ections on the multi-cultural society. His Nachleben in and outside France,1 especially in England, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United States,2 has been widely studied. It is there- fore surprising that until present no book-length study has been devoted to the multiple and various relationships between Montaigne’s Essais and the Low Countries. In fact, with the sole but notable exception of stud- ies on Erasmus and Justus Lipsius, only a handful of publications have appeared at all on the subject, and they generally restrict themselves 1 For France, see Boase M., The Fortunes of Montaigne. A History of the Essais in France, 1580–1669 (London: 1935); Villey P., Montaigne devant la postérité (Paris: 1935); Brunschvicg L., Descartes et Pascal, lecteurs de Montaigne (Neuchâtel: 1945), Dréano M., La Renommée de Montaigne en France au XVIII e siècle (1677–1802) (Angers: 1952); Millet O., La première réception des Essais de Montaigne (1580 –1640) (Paris: 1995).