Xerox University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia

‘Listen, Politics is not for Children:’ Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Henryatta Louise Ballah Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Drs. Ousman Kobo, Advisor Antoinette Errante Ahmad Sikianga i Copyright by Henryatta Louise Ballah 2012 ii Abstract This dissertation explores the historical causes of the Liberian civil war (1989- 2003), with a keen attention to the history of Liberian youth, since the beginning of the Republic in 1847. I carefully analyzed youth engagements in social and political change throughout the country’s history, including the ways by which the civil war impacted the youth and inspired them to create new social and economic spaces for themselves. As will be demonstrated in various chapters, despite their marginalization by the state, the youth have played a crucial role in the quest for democratization in the country, especially since the 1960s. I place my analysis of the youth in deep societal structures related to Liberia’s colonial past and neo-colonial status, as well as the impact of external factors, such as the financial and military support the regime of Samuel Doe received from the United States during the cold war and the influence of other African nations. I emphasize that the socio-economic and political policies implemented by the Americo- Liberians (freed slaves from the U.S.) who settled in the country beginning in 1822, helped lay the foundation for the civil war. -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

Constitution Review Committee (Crc)

CONSTITUTION REVIEW COMMITTEE (CRC) VIEWS OF THE LIBERIAN PEOPLE AS EXPRESSED DURING THE 73 ELECTORAL DISTRICTS AND DIASPORA CONSULTATIONS. BACKGROUND/INTRODUCTION Constitution reform is a key and strategic part of Liberia’s post-conflict recovery agenda which places emphasis on inclusive governance and the rule of law. This was manifested by the Administration of Madam Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf when she established the Constitution Review Committee in August, 2012. The Constitution Review Committee (CRC) has the mandate to review Liberia’s current Constitution (1986) through wide-spread public participation and to develop proposals from inputs (views, suggestions and recommendations) generated from the public interactions and discourses as the basis constitutional for amendments. In furtherance of the Committee’s mandate to ensure maximum citizens participation, the Committee determined that the guiding principle for the review process would be Bottoms up Approach to gather views and suggestions from the citizenry to derive and formulate proposals and recommendations to amend the Constitution of Liberia. The Committee also determined and resolved to conduct the review of the Constitution on critical milestones that would ensure legitimacy and confidence in of the outcome of the Review Process. The milestones adopted are: a) Organization and capacity building b) Public awareness on the provisions of the 1986 Constitution c) Civic Education d) Public Consultation e) Collating and Analysis of views/suggestions f) National Constitution Conference g) Presentation of Proposed amendments h) Legislative Action i) Publication of Gazette on Legislative approved Constitutional amendments and Public Education j) Referendum k) Final Report The Committee commenced its work by holding organizational and introductory meetings with stakeholders, role players, Partners and Donors. -

Bomi County Development Agenda 2008

Bomi County Development Agenda Republic of Liberia 2008 – 2012 Bomi County Development Agenda VISION STATEMENT The people of Bomi envisage a County with good governance and rule of law, reconciliation, peace and stability, advancement in social, economic, political, cultural and human development, active participation of youth and women, rapid industrialization, provision of electricity, increased job opportunities and improvement of the standard of living of all citizens and residents. Republic of Liberia Prepared by the County Development Committee, in collaboration with the Ministries of Planning and Economic Affairs and Internal Affairs. Supported by the UN County Support Team project, funded by the Swedish Government and UNDP. Table of Contents A MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER OF INTERNAL AFFAIRS........! iii FOREWORD..........................................................................! iv PREFACE!!............................................................................. vi BOMI COUNTY OFFICIALS....................................................! vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................! ix PART 1 - INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1.1.!Introduction................................................................................................! 1 1.2 !History........................................................................................................! 1 1.3.!Geography..................................................................................................! 1 1.4.!Demography...............................................................................................! -

Seasons in Hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis Phillip James Johnson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2004 Seasons in hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis Phillip James Johnson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Phillip James, "Seasons in hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis" (2004). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3905. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SEASONS IN HELL: CHARLES S. JOHNSON AND THE 1930 LIBERIAN LABOR CRISIS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Phillip James Johnson B. A., University of New Orleans, 1993 M. A., University of New Orleans, 1995 May 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My first debt of gratitude goes to my wife, Ava Daniel-Johnson, who gave me encouragement through the most difficult of times. The same can be said of my mother, Donna M. Johnson, whose support and understanding over the years no amount of thanks could compensate. The patience, wisdom, and good humor of David H. Culbert, my dissertation adviser, helped enormously during the completion of this project; any student would be wise to follow his example of professionalism. -

The Rise and Fall of Sterling in Liberia, 1847– 1943

Leigh A. Gardner The rise and fall of sterling in Liberia, 1847– 1943 Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Gardner, Leigh (2014) The rise and fall of sterling in Liberia, 1847–1943. Economic History Review, 67 (4). pp. 1089-1112. ISSN 0013-0117 DOI: 10.1111/1468-0289.12042 © 2014 Economic History Society This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/88849/ Available in LSE Research Online: July 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. The Rise and Fall of Sterling in Liberia, 1847-19431 Leigh A Gardner London School of Economics and Stellenbosch University [email protected] Abstract: Recent research on exchange rate regime choice in developing countries has revealed that a range of factors, from weak fiscal institutions to the inability to borrow in their own currencies, limits the range of options available to them. -

Lofa County Development Agenda Republic of Liberia Lofa County Development Agenda 2008 – 2012 County Vision Statement

Lofa County Development Agenda Republic of Liberia Lofa County Development Agenda 2008 – 2012 County Vision Statement Lofa County shall be a united, secure center of excellence in the delivery of social and infrastructure services and poverty reduction for all. Core Values Equal access to opportunities for all Lofa citizens Restoration of peace, security and the rule of law Transparent and effective governance economic growth and job creation Preservation of natural resources and environmental protection Republic of Liberia Prepared by the County Development Committee, in collaboration with the Ministries of Planning and Economic Affairs and Internal Affairs. Supported by the UN County Support Team project, funded by the Swedish Government and UNDP. Table of Contents A MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER OF INTERNAL AFFAIRS........! iii FOREWORD..........................................................................! iv PREFACE!!............................................................................. vi LOFA COUNTY OFFICIALS....................................................! viii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................! xi PART 1 - INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1.1.!Introduction................................................................................................! 1 1.2.!History........................................................................................................! 1 1.3.!Geography..................................................................................................! -

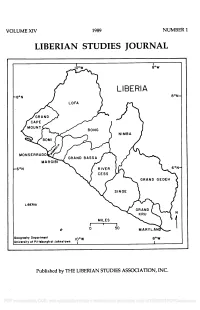

Volume Xiv 1989 Number 1 Liberian Studies Journal -8

VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL I 10 °W 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI -6°N RIVER 6°N- MILES I I 0 50 MARYLAND Geography Department °W 10 8°W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 1 I Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. El wood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Dalvan M. Coger Memphis State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Joseph S. Guannu Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS THE LIBERIAN REFINERY, A LOOK INSIDE A PARTIALLY "OPEN DOOR" ....................................................... 1 by Garland R. Farmer HARVEY S. FIRESTONE'S LIBERIAN INVESTMENT: 1922 -1932 .. 13 by Arthur J. Knoll LIBERIA AND ISRAEL: THE EVOLUTION OF A RELATIONSHIP 34 by Yekutiel Gershoni THE KRU COAST REVOLT OF 1915 -1916 ........................................... 51 by Jo Sullivan EUROPEAN INTERVENTION IN LIBERIA WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE "CADELL INCIDENT" OF 1908 -1909 . -

Humanitarian Sitrep 20

Photograph courtesy of UNHCR/ G.Gordon RESPONSE TO IVORIAN REFUGEE CRISIS IN LIBERIA Weekly Sitrep No 5 : 20 – 26 February 2011 HIGHLIGHTS AND SITUATIONAL OVERVIEW • An estimated 22,000 Ivorian Refugees crossed into Liberia between 24‐26 February 2011, more than half the total number of refugees registered between 29 November 2010 and 19 February 2011. Approximately 1,000 Ivorians had also crossed into Zwedru in the same period. The newly arrived refugees claim they fled to Liberia following the recent clashes in Touleupleu (border with Zwedru), Zouan Houye and Bin Houye (border with Buutuo) areas of Cote d’Ivoire. • The total number of Ivorian refugees registered in Liberia topped 61,000 on 26 February 2011. • A large number of refugees continue to live with host communities in border areas of Liberia. The influx of refugees is straining the capacities of host communities, and the already inadequate health and other facilities. 2,450 refugees (593 families) from the 39,784 previously registered refugees have opted to move to the Bahn camp, while 148 others (29 families) from the same caseload opted to move to one of the relocation villages. • The distance of host villages from main cities and towns, as well as extremely poor road conditions continue to hamper access to refugees and host populations, and pose serious challenges to the provision of assistance. Several kilometers of roads and dozens of bridges and culverts first need to be reconstructed before food and other items can be transported to all areas along the border, and refugees safely transported to the camp or relocation villages. -

Africa and Liberia in World Politics

© COPYRIGHT by Chandra Dunn 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED AFRICA AND LIBERIA IN WORLD POLITICS BY Chandra Dunn ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzes Liberia’s puzzling shift from a reflexive allegiance to the United States (US) to a more autonomous, anti-colonial, and Africanist foreign policy during the early years of the Tolbert administration (1971-1975) with a focus on the role played by public rhetoric in shaping conceptions of the world which engendered the new policy. For the overarching purpose of understanding the Tolbert-era foreign-policy actions, this study traces the use of the discursive resources Africa and Liberia in three foreign policy debates: 1) the Hinterland Policy (1900-05), 2) the creation of the Organization for African Unity (OAU) (1957- 1963), and finally, 3) the Tolbert administration’s autonomous, anti-colonial foreign policy (1971-1975). The specifications of Liberia and Africa in the earlier debates are available for use in subsequent debates and ultimately play a role in the adoption of the more autonomous and anti-colonial foreign policy. Special attention is given to the legitimation process, that is, the regular and repeated way in which justifications are given for pursuing policy actions, in public discourse in the United States, Europe, Africa, and Liberia. The analysis highlights how political opponents’ justificatory arguments and rhetorical deployments drew on publicly available powerful discursive resources and in doing so attempted to define Liberia often in relation to Africa to allow for certain courses of action while prohibiting others. Political actors claimed Liberia’s membership to the purported supranational cultural community of Africa. -

Post-Emancipation Barbadian Emigrants in Pursuit Of

“MORE AUSPICIOUS SHORES”: POST-EMANCIPATION BARBADIAN EMIGRANTS IN PURSUIT OF FREEDOM, CITIZENSHIP, AND NATIONHOOD IN LIBERIA, 1834 – 1912 By Caree A. Banton Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY August, 2013 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Richard Blackett Professor Jane Landers Professor Moses Ochonu Professor Jemima Pierre To all those who labored for my learning, especially my parents. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to more people than there is space available for adequate acknowledgement. I would like to thank Vanderbilt University, the Albert Gordon Foundation, the Rotary International, and the Andrew Mellon Foundation for all of their support that facilitated the research and work necessary to complete this project. My appreciation also goes to my supervisor, Professor Richard Blackett for the time he spent in directing, guiding, reading, editing my work. At times, it tested his patience, sanity, and will to live. But he persevered. I thank him for his words of caution, advice and for being a role model through his research and scholarship. His generosity and kind spirit has not only shaped my academic pursuits but also my life outside the walls of the academy. I would also like to express my sincere thanks to the members of my dissertation committee: Jane Landers, Moses Ochonu, and Jemima Pierre. They have provided advice and support above and beyond what was required of them. I am truly grateful not only for all their services rendered but also the kind words and warm smiles with which they have always greeted me. -

Mapping Maternal and Newborn Healthcare Access in West African Countries

Mapping maternal and newborn healthcare access in West African Countries Dorothy Ononokpono, Bernard Baffour and Alice Richardson Introduction Improvement in maternal and newborn health in developing countries has been a major priority in public health since the 1980s. This is reflected in the consensus reached at different international conferences, such as the Safe Motherhood conference in Nairobi in 1987 and the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994, as well as specific targets in the Millennium and Sustainable Development Goals. In spite of these efforts to increase access to reproductive health services and reduce maternal mortality, maternal health is still poor in most developing countries. Globally, about 830 women die from pregnancy- or childbirth-related complications every day, and it was estimated that in 2015, roughly 303 000 women died during pregnancy and childbirth1. Unfortunately, almost all of these deaths (99%) occurred in low-resource settings, and most could have been prevented with adequate access to healthcare. Although a number of countries in sub-Saharan Africa halved their levels of maternal mortality since 1990, mortality rates for newborn babies have been slow to decline compared with death rates for older infants. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), target 3.1, is to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100 000 live births by 2030 and improve maternal and child health. For this target to be achievable and realized there has to be a concerted effort to improve the maternal and newborn health in low income countries, and in particular in the sub-Saharan African region.