Playing the Past: History and Nostalgia in Video Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Games Auction- 840 N. 10Th Street Sacramento - August 21

09/25/21 02:04:36 Video Games Auction- 840 N. 10th Street Sacramento - August 21 Auction Opens: Tue, Aug 18 8:20am PT Auction Closes: Fri, Aug 21 10:00am PT Lot Title Lot Title HA9500 PS4 Overcooked HA9533 Nintendo DS Safe Cracker HA9501 Wii Sega Superstars Tennis HA9534 Diablo HA9502 PCDVD Prince of Persia HA9535 Diablo HA9503 PCDVD Prince of Persia HA9504 Tropico 5 PC DVD-ROM Software HA9505 Nintendo Switch Runbow Deluxe Edition HA9506 XBOXONE Mirrors Edge Catalyst HA9507 XBOX 360 Dungeon Siege HA9508 PS4 Special Edition HA9509 XBOXONE The Golf Club 2019 HA9510 XBOX lood Bowl HA9511 Konami PES 2011 HA9512 Play Station 2 Wave Rally HA9513 XBOXONE Shinobi Striker HA9514 New Nintendo 3DS Minecraft HA9515 Nintendo 3DS Super Smash Bros HA9516 PS4 Call of Duty Black Ops HA9517 Nintendo Switch NBA 2K20 HA9518 XBOXONE Grid HA9519 PS4 Sims4 Bundle HA9520 Quit for Good My Stop Smoking Coach HA9521 PS4 Subnautica HA9522 Wii Ultimate Duck Hunting HA9523 PS4 Lego City HA9524 PS4 Lego City HA9525 XBOXONE game HA9526 XBOXONE Tennis World Tour HA9527 PS4 Injustice 2 HA9528 Nintendo Switch Mario Cart HA9529 XBOXONE Red Dead Redemption HA9530 XBOXONE NBA2K19 HA9531 Pixel in 3D HA9532 Battlefield 1942 Road to Rome 1/2 09/25/21 02:04:36 Full payment for all items must be received within 5 days of the auction closing date, this includes Sundays and Holidays. This payment deadline is firm. All items not paid for by the payment deadline will be considered abandoned, the winning bidders claim to those items will be forfeited and a 15% relisting fee will be charged. -

Xbox Cheats Guide Ght´ Page 1 10/05/2004 007 Agent Under Fire

Xbox Cheats Guide 007 Agent Under Fire Golden CH-6: Beat level 2 with 50,000 or more points Infinite missiles while in the car: Beat level 3 with 70,000 or more points Get Mp model - poseidon guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 11 Get regenerative armor: Get 130000 points for level 11 Get golden bullets: Get 120000 points for level 10 Get golden armor: Get 110000 points for level 9 Get MP weapon - calypso: Get 100000 points and all 007 medallions for level 8 Get rapid fire: Get 100000 points for level 8 Get MP model - carrier guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 12 Get unlimited ammo for golden gun: Get 130000 points on level 12 Get Mp weapon - Viper: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 6 Get Mp model - Guard: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 5 Mp modifier - full arsenal: Get 110000 points and all 007 medallions in level 9 Get golden clip: Get 90000 points for level 5 Get MP power up - Gravity boots: Get 70000 points and all 007 medallions for level 4 Get golden accuracy: Get 70000 points for level 4 Get mp model - Alpine Guard: Get 100000 points and all gold medallions for level 7 ghðtï Page 1 10/05/2004 Xbox Cheats Guide Get ( SWEET ) car Lotus Espirit: Get 100000 points for level 7 Get golden grenades: Get 90000 points for level 6 Get Mp model Stealth Bond: Get 70000 points and all gold medallions for level 3 Get Golden Gun mode for (MP): Get 50000 points and all 007 medallions for level 2 Get rocket manor ( MP ): Get 50000 points and all gold 007 medalions on first level Hidden Room: On the level Bad Diplomacy get to the second floor and go right when you get off the lift. -

Art. Music. Games. Life. 16 09

ART. MUSIC. GAMES. LIFE. 16 09 03 Editor’s Letter 27 04 Disposed Media Gaming 06 Wishlist 07 BigLime 08 Freeware 09 Sonic Retrospective 10 Alexander Brandon 12 Deus Ex: Invisible War 20 14 Game Reviews Music 16 Kylie Showgirl Tour 18 Kylie Retrospective 20 Varsity Drag 22 Good/Bad: Radio 1 23 Doormat 25 Music Reviews Film & TV 32 27 Dexter 29 Film Reviews Comics 31 Death Of Captain Marvel 32 Blankets 34 Comic Reviews Gallery 36 Andrew Campbell 37 Matthew Plater 38 Laura Copeland 39 Next Issue… Publisher/Production Editor Tim Cheesman Editor Dan Thornton Deputy Editor Ian Moreno-Melgar Art Editor Andrew Campbell Sub Editor/Designer Rachel Wild Contributors Keith Andrew/Dan Gassis/Adam Parker/James Hamilton/Paul Blakeley/Andrew Revell Illustrators James Downing/Laura Copeland Cover Art Matthew Plater [© Disposable Media 2007. // All images and characters are retained by original company holding.] dm6/editor’s letter as some bloke once mumbled. “The times, they are You may have spotted a new name at the bottom of this a-changing” column, as I’ve stepped into the hefty shoes and legacy of former Editor Andrew Revell. But luckily, fans of ‘Rev’ will be happy to know he’s still contributing his prosaic genius, and now he actually gets time to sleep in between issues. If my undeserved promotion wasn’t enough, we’re also happy to announce a new bi-monthly schedule for DM. Natural disasters and Acts of God not withstanding. And if that isn’t enough to rock you to the very foundations of your soul, we’re also putting the finishing touches to a newDisposable Media website. -

2018 – Volume 6, Number

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2 & 3 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor KEVIN CALCAMP Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Bump in the Night” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of Pixabay/Kellepics EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH PAUL BOOTH Minnesota State University, Moorhead DePaul University GARY BURNS ANNE M. CANAVAN Northern Illinois University Salt Lake Community College BRIAN COGAN ASHLEY M. DONNELLY Molloy College Ball State University LEIGH H. EDWARDS KATIE FREDICKS Florida State University Rutgers University ART HERBIG ANDREW F. HERRMANN Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO KATHLEEN A. KENNEDY Maryville University of St. Louis Missouri State University SARAH MCFARLAND TAYLOR KIT MEDJESKY Northwestern University University of Findlay CARLOS D. MORRISON SALVADOR MURGUIA Alabama State University Akita International -

Mlb Slugfest 2003 Ps2 Cheats

Mlb slugfest 2003 ps2 cheats GCN Cheats - MLB SlugFest This page contains a list of cheats, codes, Easter eggs, tips, and other secrets for MLB SlugFest for. The best place to get cheats, codes, cheat codes, walkthrough, guide, FAQ, unlockables, tricks, and secrets for PlayStation 2 (PS2). MLB SlugFest For MLB Slugfest on the PlayStation 2, GameFAQs has 24 cheat codes and secrets. MLB Slugfest Cheats. MLB Slugfest Cheats. Xbox | Submitted by The are made Up No Contact Mode Left. PS2 | Submitted by Goofy. Get the latest MLB Slugfest cheats, codes, unlockables, hints, Easter eggs, glitches, tips, tricks, hacks, downloads, hints, guides, FAQs, walkthroughs, and. Get the latest MLB Slugfest cheats, codes, unlockables, hints, Easter eggs, Check PlayStation 2 cheats for this gameCheck Xbox cheats for this game. MLB Slugfest cheats, codes, walkthroughs, guides, FAQs and more for PlayStation 2. MLB Slugfest Playstation 2 Cheats: At the Match-Up screen, press Square, Triangle, and Circle to change the icons in the first, second, and third boxes. Midway's MLB Slugfest brings some good, clean fun back to a genre teeming with stodgy MLB Slugfest / PlayStation 2. The Good. For MLB Slugfest on the PlayStation 2, GameRankings has 24 cheat codes and secrets. Slugfest tops sales. MLB Slugfest Review: / Find all our MLB SlugFest Cheats for Xbox. Plus great forums We also have cheats for this game on: PlayStation 2 GameCube. Latest; Your Cheats. Playstation 2 (PS2) - MLB Slugfest Midnight Club 2 Cheat Codes, Cokemusic Cheats and The Sims Cheats For Ps2 from. MLB Slugfest Part 1. NdamukongSuhFan Loading Unsubscribe Game. -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Marzo 2019 Escuela Superior De Arte Del Principado De Asturias ISSN 2603-9079 ISSN 2603-9079

Nº 3 ◊ marzo 2019 Escuela Superior de Arte del Principado de Asturias ISSN 2603-9079 ISSN 2603-9079 JORNADAS CONSERVACIÓN XII Y RESTAURACIÓN actas Imagen y sonido: Memoria clave de nuestro Patrimonio Cultural Avilés, 15 y 16 de marzo de 2018 JORNADAS CONSERVACIÓN XII Y RESTAURACIÓN actas Imagen y sonido: Memoria clave de nuestro Patrimonio Cultural Actas de las XII Jornadas de Conservación y Restauración de Bienes Culturales “Imagen y sonido: Memoria clave de nuestro Patrimonio Cultural”. Avilés, 15 y 16 de marzo de 2018. Organización de las Jornadas Escuela Superior de Arte del Principado de Asturias Coordinación de las Jornadas Gema Puente Peinador, Soraya Andrés Antolín Comunicación visual de las Jornadas Sandra Pérez Suárez y Xandra Muñoz Gómez, alumnas de Diseño Gráfico Edición Escuela Superior de Arte del Principado de Asturias Consejería de Educación y Cultura del Gobierno del Principado de Asturias Comité editorial Luis Suárez Saro Diseño de la revista Sara Pérez Suárez y Xandra Muñoz Gómez, alumnas de Diseño Gráfico, bajo la dirección de José Ramón Pedreira Díaz y Marlén García Vázquez ISSN: 2603-9079 Fecha de publicación: Marzo de 2019 La Escuela Superior de Arte del Principado de Asturias no se responsabiliza de la información contenida en los artículos incluidos en esta revista ni se identifica necesariamente con ella. Esta publicación utiliza una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento - No Comercial – Sin Obra Derivada CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Se permite compartir, copiar, distribuir y comunicar públicamente la obra con el reconocimiento expreso de su autoría y procedencia. No se permite un uso comercial de la obra original ni la generación de obras derivadas. -

Aircraft Collection

A, AIR & SPA ID SE CE MU REP SEU INT M AIRCRAFT COLLECTION From the Avenger torpedo bomber, a stalwart from Intrepid’s World War II service, to the A-12, the spy plane from the Cold War, this collection reflects some of the GREATEST ACHIEVEMENTS IN MILITARY AVIATION. Photo: Liam Marshall TABLE OF CONTENTS Bombers / Attack Fighters Multirole Helicopters Reconnaissance / Surveillance Trainers OV-101 Enterprise Concorde Aircraft Restoration Hangar Photo: Liam Marshall BOMBERS/ATTACK The basic mission of the aircraft carrier is to project the U.S. Navy’s military strength far beyond our shores. These warships are primarily deployed to deter aggression and protect American strategic interests. Should deterrence fail, the carrier’s bombers and attack aircraft engage in vital operations to support other forces. The collection includes the 1940-designed Grumman TBM Avenger of World War II. Also on display is the Douglas A-1 Skyraider, a true workhorse of the 1950s and ‘60s, as well as the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk and Grumman A-6 Intruder, stalwarts of the Vietnam War. Photo: Collection of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum GRUMMAN / EASTERNGRUMMAN AIRCRAFT AVENGER TBM-3E GRUMMAN/EASTERN AIRCRAFT TBM-3E AVENGER TORPEDO BOMBER First flown in 1941 and introduced operationally in June 1942, the Avenger became the U.S. Navy’s standard torpedo bomber throughout World War II, with more than 9,836 constructed. Originally built as the TBF by Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, they were affectionately nicknamed “Turkeys” for their somewhat ungainly appearance. Bomber Torpedo In 1943 Grumman was tasked to build the F6F Hellcat fighter for the Navy. -

BATTLEFIELD 1942 Joel Bengt Eriksson, Arr

BATTLEFIELD 1942 Joel Bengt Eriksson, arr. Sam Daniels Grade / Moeilijkheidsgraad / Degré de difficulté / Schwierigkeitsgrad / Difficoltà 3 Duration / Tijdsduur / Durée / Dauer / Durata 4:23 Recording on / Opname op / Enregistrement sur / Aufnahme auf / Registrazione su Tierolff for Band No. 28 "TWO MARIMBA REFLECTIONS" LMCD-12402 Tierolff Muziekcentrale Postbus 18 Markt 90-92 4700 AA Roosendaal/Nederland Tel.: ++ 31 (0) 165 541255 Fax: ++ 31 (0) 165 558339 Website: www.tierolff.nl E-mail: [email protected] N Young Concert Band O I Full score 1 T A Flute 5 S T T Oboe (optional) 1 N Bassoon (optional) 1 R A E Bb Clarinet 1 5 M Bb Clarinet 2 5 P U Bb Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 R Eb Alto Saxophone 3 Y T Bb Tenor Saxophone 2 R A S Eb Baritone Saxophone (opt.) 1 Bb Soprano Saxophone 1 N Bb Trumpet 1 3 T Bb Flugelhorn 1 1 I Bb Trumpet 2 3 N Bb Flugelhorn 2 1 F Horn 2 E Eb Horn 2 C Trombone 3 M Bb Trombone bass clef 1 C Euphonium 2 E Bb Trombone treble clef 2 Bb Euphonium treble clef 3 L Bb Euphonium bass clef 2 C Bass 2 P Eb Bass treble clef 1 Snare Drum/Bass Drum 2 P Eb Bass bass clef 1 Percussion 1 U Bb Bass treble clef 1 Timpani 1 S Bb Bass bass clef 1 BATTLEFIELD 1942 English: Video gaming is all the rage, and it’s not only young people that participate. There are adults, too, who are just as passionate. Battlefield 1942 is based on World War II, and its music is impressive, accompanying a game filled with weapons, vehicles, maps and battles. -

GAME DEVELOPERS a One-Of-A-Kind Game Concept, an Instantly Recognizable Character, a Clever Phrase— These Are All a Game Developer’S Most Valuable Assets

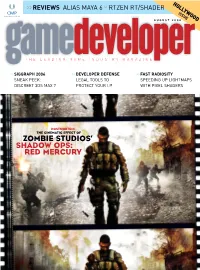

HOLLYWOOD >> REVIEWS ALIAS MAYA 6 * RTZEN RT/SHADER ISSUE AUGUST 2004 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>SIGGRAPH 2004 >>DEVELOPER DEFENSE >>FAST RADIOSITY SNEAK PEEK: LEGAL TOOLS TO SPEEDING UP LIGHTMAPS DISCREET 3DS MAX 7 PROTECT YOUR I.P. WITH PIXEL SHADERS POSTMORTEM: THE CINEMATIC EFFECT OF ZOMBIE STUDIOS’ SHADOW OPS: RED MERCURY []CONTENTS AUGUST 2004 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 7 FEATURES 14 COPYRIGHT: THE BIG GUN FOR GAME DEVELOPERS A one-of-a-kind game concept, an instantly recognizable character, a clever phrase— these are all a game developer’s most valuable assets. To protect such intangible properties from pirates, you’ll need to bring out the big gun—copyright. Here’s some free advice from a lawyer. By S. Gregory Boyd 20 FAST RADIOSITY: USING PIXEL SHADERS 14 With the latest advances in hardware, GPU, 34 and graphics technology, it’s time to take another look at lightmapping, the divine art of illuminating a digital environment. By Brian Ramage 20 POSTMORTEM 30 FROM BUNGIE TO WIDELOAD, SEROPIAN’S BEAT GOES ON 34 THE CINEMATIC EFFECT OF ZOMBIE STUDIOS’ A decade ago, Alexander Seropian founded a SHADOW OPS: RED MERCURY one-man company called Bungie, the studio that would eventually give us MYTH, ONI, and How do you give a player that vicarious presence in an imaginary HALO. Now, after his departure from Bungie, environment—that “you-are-there” feeling that a good movie often gives? he’s trying to repeat history by starting a new Zombie’s answer was to adopt many of the standard movie production studio: Wideload Games. -

Vintage Game Consoles: an INSIDE LOOK at APPLE, ATARI

Vintage Game Consoles Bound to Create You are a creator. Whatever your form of expression — photography, filmmaking, animation, games, audio, media communication, web design, or theatre — you simply want to create without limitation. Bound by nothing except your own creativity and determination. Focal Press can help. For over 75 years Focal has published books that support your creative goals. Our founder, Andor Kraszna-Krausz, established Focal in 1938 so you could have access to leading-edge expert knowledge, techniques, and tools that allow you to create without constraint. We strive to create exceptional, engaging, and practical content that helps you master your passion. Focal Press and you. Bound to create. We’d love to hear how we’ve helped you create. Share your experience: www.focalpress.com/boundtocreate Vintage Game Consoles AN INSIDE LOOK AT APPLE, ATARI, COMMODORE, NINTENDO, AND THE GREATEST GAMING PLATFORMS OF ALL TIME Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton First published 2014 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Taylor & Francis The right of Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

\0-9\0 and X ... \0-9\0 Grad Nord ... \0-9\0013 ... \0-9\007 Car Chase ... \0-9\1 X 1 Kampf ... \0-9\1, 2, 3

... \0-9\0 and X ... \0-9\0 Grad Nord ... \0-9\0013 ... \0-9\007 Car Chase ... \0-9\1 x 1 Kampf ... \0-9\1, 2, 3 ... \0-9\1,000,000 ... \0-9\10 Pin ... \0-9\10... Knockout! ... \0-9\100 Meter Dash ... \0-9\100 Mile Race ... \0-9\100,000 Pyramid, The ... \0-9\1000 Miglia Volume I - 1927-1933 ... \0-9\1000 Miler ... \0-9\1000 Miler v2.0 ... \0-9\1000 Miles ... \0-9\10000 Meters ... \0-9\10-Pin Bowling ... \0-9\10th Frame_001 ... \0-9\10th Frame_002 ... \0-9\1-3-5-7 ... \0-9\14-15 Puzzle, The ... \0-9\15 Pietnastka ... \0-9\15 Solitaire ... \0-9\15-Puzzle, The ... \0-9\17 und 04 ... \0-9\17 und 4 ... \0-9\17+4_001 ... \0-9\17+4_002 ... \0-9\17+4_003 ... \0-9\17+4_004 ... \0-9\1789 ... \0-9\18 Uhren ... \0-9\180 ... \0-9\19 Part One - Boot Camp ... \0-9\1942_001 ... \0-9\1942_002 ... \0-9\1942_003 ... \0-9\1943 - One Year After ... \0-9\1943 - The Battle of Midway ... \0-9\1944 ... \0-9\1948 ... \0-9\1985 ... \0-9\1985 - The Day After ... \0-9\1991 World Cup Knockout, The ... \0-9\1994 - Ten Years After ... \0-9\1st Division Manager ... \0-9\2 Worms War ... \0-9\20 Tons ... \0-9\20.000 Meilen unter dem Meer ... \0-9\2001 ... \0-9\2010 ... \0-9\21 ... \0-9\2112 - The Battle for Planet Earth ... \0-9\221B Baker Street ... \0-9\23 Matches ..