History of the Presbyterian Churches of the World, Adapted for Use in the Class Room

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elspeth Buchan and the Buchanite Movement

Elspeth Buchan and the Buchanite Movement Author: Jill Strong Author: Rowan Strong Published: 27th April 2021 Jill Strong and Rowan Strong. "Elspeth Buchan and the Buchanite Movement." In James Crossley and Alastair Lockhart (eds.) Critical Dictionary of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements. 27 April 2021. Retrieved from www.cdamm.org/articles/buchanites Origins of the Buchanite Sect Elspeth Buchan (1738–91), the wife of a potter at the Broomielaw Delftworks in Glasgow, Scotland, and mother of three children, heard Hugh White, minister of the Irvine Relief Church since 1782, preach at a Sacrament in Glasgow in December 1782. As the historian of such great occasions puts it, ‘Sacramental [ie Holy Communion] occasions in Scotland were great festivals, an engaging combination of holy day and holiday’, held over a number of days, drawing people from the surrounding area to hear a number of preachers. Robert Burns composed one of his most famous poems about them, entitled ‘The Holy Fair’ (Schmidt 1989, 3).Consequently, she entered into correspondence with him in January 1793, identifying White as the person purposed by God to share in a divine commission to prepare a righteous people for the second coming of Christ. Buchan had believed she was the recipient of special insights from God from as early as 1774, but she had received little encouragement from the ministers she had approached to share her ‘mind’ (Divine Dictionary, 79). The spiritual mantle proffered by Buchan was willingly taken up by White. When challenged over erroneous doctrine by the managers and elders of the Relief Church there within three weeks of Buchan’s arrival in Irvine in March 1783, White refused to desist from preaching both publicly and privately Buchan’s claim of a divine commission to prepare for the second coming of Christ. -

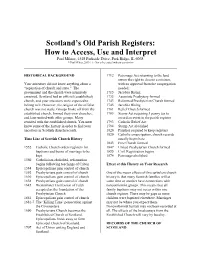

Scotland's Old Parish Registers: How to Access, Use and Interpret

Scotland’s Old Parish Registers: How to Access, Use and Interpret Paul Milner, 1548 Parkside Drive, Park Ridge, IL 6068 © Paul Milner, 2003-11 - Not to be copied without permission HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1712 Patronage Act returning to the land owner the right to choose a minister, Your ancestors did not know anything about a with no approval from the congregation “separation of church and state.” The needed. government and the church were intimately 1715 Jacobite Rising entwined. Scotland had an official (established) 1733 Associate Presbytery formed church, and your ancestors were expected to 1743 Reformed Presbyterian Church formed belong to it. However, the religion of the official 1745 Jacobite Rising church was not static. Groups broke off from the 1761 Relief Church formed established church, formed their own churches, 1783 Stamp Act requiring 3 penny tax to and later united with other groups. Many record an event in the parish register reunited with the established church. You must 1793 Catholic Relief Act know some of the history in order to find your 1794 Stamp Act abolished ancestors in Scottish church records. 1820 Parishes required to keep registers 1829 Catholic emancipation, church records Time Line of Scottish Church History usually begin here 1843 Free Church formed 1552 Catholic Church orders registers for 1847 United Presbyterian Church formed baptisms and banns of marriage to be 1855 Civil Registration begins kept 1874 Patronage abolished 1560 Catholicism abolished, reformation begins following teachings of Calvin Effect of this History on Your Research 1584 Episcopalians gain control of church 1592 Presbyterians gain control of church One of the major effects of this turbulent church 1610 Episcopalians gain control of church history is that many Scottish families will at 1638 Presbyterians gain control of church some time or another have connections with 1645 Westminster Confession of Faith nonconformist groups. -

A Singular Solace: an Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000

A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 David William Dutton BA, MTh October 2020 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Stirling for the degree of Master of Philosophy in History. Division of History and Politics 1 Research Degree Thesis Submission Candidates should prepare their thesis in line with the code of practice. Candidates should complete and submit this form, along with a soft bound copy of their thesis for each examiner, to: Student Services Hub, 2A1 Cottrell Building, or to [email protected]. Candidate’s Full Name: DAVID WILLIAM DUTTON Student ID: 2644948 Thesis Word Count: 49,936 Maximum word limits include appendices but exclude footnotes and bibliographies. Please tick the appropriate box MPhil 50,000 words (approx. 150 pages) PhD 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by publication) 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by practice) 40,000 words (approx. 120 pages) Doctor of Applied Social Research 60,000 words (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Business Administration 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Education 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Midwifery / Nursing / Professional Health Studies 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Diplomacy 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Thesis Title: A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 Declaration I wish to submit the thesis detailed above in according with the University of Stirling research degree regulations. I declare that the thesis embodies the results of my own research and was composed by me. Where appropriate I have acknowledged the nature and extent of work carried out in collaboration with others included in the thesis. -

Patrick Henry

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY PATRICK HENRY: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF HARMONIZED RELIGIOUS TENSIONS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE HISTORY DEPARTMENT IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY BY KATIE MARGUERITE KITCHENS LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA APRIL 1, 2010 Patrick Henry: The Significance of Harmonized Religious Tensions By Katie Marguerite Kitchens, MA Liberty University, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Samuel Smith This study explores the complex religious influences shaping Patrick Henry’s belief system. It is common knowledge that he was an Anglican, yet friendly and cooperative with Virginia Presbyterians. However, historians have yet to go beyond those general categories to the specific strains of Presbyterianism and Anglicanism which Henry uniquely harmonized into a unified belief system. Henry displayed a moderate, Latitudinarian, type of Anglicanism. Unlike many other Founders, his experiences with a specific strain of Presbyterianism confirmed and cooperated with these Anglican commitments. His Presbyterian influences could also be described as moderate, and latitudinarian in a more general sense. These religious strains worked to build a distinct religious outlook characterized by a respect for legitimate authority, whether civil, social, or religious. This study goes further to show the relevance of this distinct religious outlook for understanding Henry’s political stances. Henry’s sometimes seemingly erratic political principles cannot be understood in isolation from the wider context of his religious background. Uniquely harmonized -

Reformed Tradition

THE ReformedEXPLORING THE FOUNDATIONS Tradition: OF FAITH Before You Begin This will be a brief overview of the stream of Christianity known as the Reformed tradition. The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, the Reformed Church in America, the United Church of Christ, and the Christian Reformed Church are among those considered to be churches in the Reformed tradition. Readers who are not Presbyterian may find this topic to be “too Presbyterian.” We encourage you to find out more about your own faith tradition. Background Information The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) is part of the Reformed tradition, which, like most Christian traditions, is ancient. It began at the time of Abraham and Sarah and was Jewish for about two thousand years before moving into the formation of the Christian church. As Christianity grew and evolved, two distinct expressions of Christianity emerged, and the Eastern Orthodox expression officially split with the Roman Catholic expression in the 11th century. Those of the Reformed tradition diverged from the Roman Catholic branch at the time of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. Martin Luther of Germany precipitated the Protestant Reformation in 1517. Soon Huldrych Zwingli was leading the Reformation in Switzerland; there were important theological differences between Zwingli and Luther. As the Reformation progressed, the term “Reformed” became attached to the Swiss Reformation because of its insistence on References Refer to “Small Groups 101” in The Creating WomanSpace section for tips on leading a small group. Refer to the “Faith in Action” sections of Remembering Sacredness for tips on incorporating spiritual practices into your group or individual work with this topic. -

H702 Church and the World in the 20Th Century

HT506 Church and the World John R. Muether, Instructor Spring 2012 [email protected] Wednesday, 1 – 4 pm Office Hours: Tuesday, 9 am to noon An examination of the relationship between the church and modern culture and a survey of the history of American Presbyterianism in the past 300 years. Particular attention is given to differing Christian approaches to the relationship of Christ and culture, and to the impact of secularization and modernization on the ministry of the church. Course Requirements 1. Class Attendance and Participation 2. Reading Reports (15 %) 3. Denominational Analysis Paper (35 %) 4. Technology Assignment (20 %) 5. Final Examination (30 %) Reading Schedule and Assignments (subject to change): 1. The Church Against the World (electronically distributed; readings assigned more or less weekly) 2. Machen, Christianity and Liberalism (Response due: TBA) 3. Berry, What are People For?(Response due: TBA) 4. Hunter, To Change the World (Response due: TBA) 5. Technology Assignment (5-7 page paper, due: TBA) 6. Denominational analysis paper (8-10 page paper, due: May 18) Outline of the Course Part I: Church and World (1 – 2 pm) Introduction to the Class I. Preliminary Notes on Culture A. Pilgrimage as a Metaphor for the Christian Life B. What is Culture? C. What is the Church? D. What is the World? E. Heresies at the Intersection: Manichaeism, Gnosticism, Docetism F. Common Grace and the Antithesis II. Christ and Culture: “The Enduring Problem” A. H. Richard Niebuhr: Christ and Culture B. Critiques of Niebuhr C. Reformed Approaches to Culture III. The Contours of the Modern World: The Enlightenment & Its Effects A. -

Researching Huguenot Settlers in Ireland

BYU Family Historian Volume 6 Article 9 9-1-2007 Researching Huguenot Settlers in Ireland Vivien Costello Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byufamilyhistorian Recommended Citation The BYU Family Historian, Vol. 6 (Fall 2007) p. 83-163 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Family Historian by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. RESEARCHING HUGUENOT SETTLERS IN IRELAND1 VIVIEN COSTELLO PREAMBLE This study is a genealogical research guide to French Protestant refugee settlers in Ireland, c. 1660–1760. It reassesses Irish Huguenot settlements in the light of new findings and provides a background historical framework. A comprehensive select bibliography is included. While there is no formal listing of manuscript sources, many key documents are cited in the footnotes. This work covers only French Huguenots; other Protestant Stranger immigrant groups, such as German Palatines and the Swiss watchmakers of New Geneva, are not featured. INTRODUCTION Protestantism in France2 In mainland Europe during the early sixteenth century, theologians such as Martin Luther and John Calvin called for an end to the many forms of corruption that had developed within the Roman Catholic Church. When their demands were ignored, they and their followers ceased to accept the authority of the Pope and set up independent Protestant churches instead. Bitter religious strife throughout much of Europe ensued. In France, a Catholic-versus-Protestant civil war was waged intermittently throughout the second half of the sixteenth century, followed by ever-increasing curbs on Protestant civil and religious liberties.3 The majority of French Protestants, nicknamed Huguenots,4 were followers of Calvin. -

The Distinctive Doctrines and Polity of Presbyterianism

72 Centennial of Presbyterianism in Kentucky. THE DISTINCTIVE DOCTRINES AND POLITY OF PRES- BYTERIANISM. _________ BY REV. T. D. WITHERSPOON, D. D. ________ Every denomination of Christians has certain distinctive prin- ciples, which serve to differentiate it from other branches of the visible Church, and which constitute its raison d’etre—the ground more or less substantial of its separate organic existence. In proportion as these principles are vital and fundamental, they vindicate the body that becomes their exponent from the charge of faction or schism, and justify its maintenance of an organiza- tion separate and apart from that of all who traverse or reject them. We are met to-day as Presbyterians. We have come to com- memorate the first settlement of Presbyterianism in Kentucky. You have listened to the eloquent addresses of those who have traced the history of our Church in this commonwealth for a hun- dred years. They have told you of the first planting in this Western soil of a tender branch from our old and honored Pres- byterian stock, of the storms it has encountered, of the rough winds that have beaten upon it, and yet of its steady growth through summer’s drought and winter’s chill, until what was erstwhile but a frail and tender plant, has become a sturdy oak with roots deep-locked in the soil, with massive trunk and goodly boughs and widespread branches overshadowing the land. You have heard also, the thrilling narratives of the lives of those heroic men by whose personal ministry the Church was founded; of the toils they underwent, of the perils they encount- ered, of the hardships they endured that they might plant the standards of Presbyterianism in these Western wilds. -

Pastoral Transitions Commission Report Called Meeting of Presbytery of Transylvania September 27, 2018

Pastoral Transitions Commission Report Called Meeting of Presbytery of Transylvania September 27, 2018 The Pastoral Transitions Commission presents two candidates to be examined for ordination to the office of Teaching Elder/Minister of Word and Sacrament: 1. Andrew Bowman, called as Pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Somerset, is a under care of the Presbytery of Western North Carolina and has been certified ready for examination by a presbytery having completed all other requirements for ordination (G- 2.06). The Pastoral Transitions Commission approved the following call and terms at its meeting on July 18, 2018: Andrew Bowman (Candidate for Ordination) as Pastor (Full-time) of First Presbyterian Church, Somerset effective October 8, 2018 Cash Salary $31,000.00 Housing 14,000.00 Total $45,000.00 SECA 3,442.50 Board of Pensions (full participation) Reimbursable Allowances: Auto Allowance IRS rate up to 3,000.00 Continuing Education 1,500.00 Moving Expenses – reasonable and approved in advance, plus $1,000.00 relocation bonus. Vacation – 4 weeks annually Continuing Education Leave – 2 weeks annually Consideration of 10 weeks of sabbatical leave after 6 years of service 2. Rachel VanKirk Matthews, called as Associate Pastor of Maxwell Street Presbyterian Church, is under care of the Presbytery of Sheppards & Lapsley, and has been certified ready for examination by a presbytery having completed all other requirements for ordination (G-2.06). The Pastoral Transitions Commission approved the following call and terms at its meeting on -

Pictorial Collection at the Huguenot Library

The Huguenot Library University College London Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT Tel: 020 7679 2046 [email protected] Pictorial collection at the Huguenot Library Whilst some of the pictures held at the Library are quite old, not all of them are originals. As a consequence, the Library may not be able to provide copies for reproduction purposes or copyright permissions for some of the images listed below. The Library’s policy concerning copyright and images is available for consultation on the website, and the Librarian will happily answer any enquiries. More pictorial material (mostly related to crafts and Huguenot buildings) is held in the Subject Folders at the library, and these are listed at the Library. Please contact the Librarian if you are looking for a specific image. Enquiries relating to copyright permissions should be addressed to the Hon. Secretary of the Huguenot Society of Great Britain and Ireland ([email protected]). People Subject Format Call number Portraits of Louis XIV and others; scene of the destruction of heresy Line engraving HL 146 Chauvet family Photograph HL 148.1 “The critics of St Alban’s Abbey”, Joshua W. Butterworth, George Photograph HL 153 Lambert, Charles John Shoppee Scene including Henry VIII of England Line engraving HL 253 Cardinal of Lorraine, Duke of Guise and Catherine de Medici concerning Line engraving HL 264 the conspiracy of Amboise 1 Popes Paul III and Eugene IV Line engraving HL 284 Susanna Ames (resident of the French Hospital) Pencil drawing HL 1 Pierre Bayle Line engraving HL 4 Charles Bertheau (1657-1732) Line engraving HL 8 Theodore de Beze Lithograph HL 9 Samuel Bochart (1599-1667) Line engraving HL 137 Louis de Bourbon, prince de Condé (1621-1686) Line engraving HL 10 Claude Brousson (1647-1698) Line engraving HL 11 Claude Brousson (1647-1698) Photograph of painting by Bronckhorst HL 165.1, 165.2 Arthur Giraud Browning Photograph HL 140 Frederick Campbell (1729-1816) Mezzotint HL 13 Jacques-Nompar de Caumont, duc de la Force (1558-1652) Line engraving HL 91 Charles IX of France (d. -

Cranmer Memorial Bible College and Seminary

Cranmer Memorial Bible College and Seminary Thesis Proposal Research into Huguenots History and Theology: The Huguenots fight for religious liberty in France from 1555 to 1789 and, Calvin theological legacy. Presented to the Faculty By Mr. Tiowa Diarra October 2003 Chapter I. Introducing the problem: In 1998, the French people celebrated the 4th centennial of the Edict of Nantes, signed by Henry IV on April 13, 1598. This was a significant event to remember the great combat fought centuries ago by the Huguenot people for religious liberty in France. The promulgation of the Edict was a major step in religious freedom. It ended the thirty years of religious war and brought the reformed worship into legality in many part of the Kingdom at that time. However, Ludwig XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes on October 22, 1685 nearly a century later, delaying the religious liberty process. Recently, a celebration held in Basel, Switzerland has remarkably shown the importance of the Huguenots’ contribution in that city. A lecturer pointed out the outcome of the Huguenots contribution to the cities where they reached out as refugees like this: This city shows how much the fleeing of brains can be profitable. We can find some in history; thus, when Ludwig XIV, the Sun-King, revoked the edict of Nantes, the French Protestants did not have another choice than to convert or leave the country. Many among them were the best in arts, in science and, in business. Their escape as refugees in Switzerland, in hospitable cities such as Geneva, Zurich, Berne or Basel. -

Presbyterian and Reformed Churches

Presbyterian and Reformed Churches Presbyterian and Reformed Churches A Global History James Edward McGoldrick with Richard Clark Reed and !omas Hugh Spence Jr. Reformation Heritage Books Grand Rapids, Michigan Preface In 1905 Richard Clark Reed (1851–1925), then professor of church history at Columbia !eological Seminary, produced his History of the Presbyterian Churches of the World . Westminster Press published the book, and it soon became a widely read survey of Presbyterian and Reformed growth around the globe. Reed followed his father into the ministry of the Presbyterian Church in the United States after study at King College and Union !eologi- cal Seminary in Virginia. !e future historian was pastor of congregations in Tennessee, Virginia, and North Carolina before he joined the faculty of Columbia !eological Seminary in 1898. In addition to his pastoral and professorial labors, Reed was associate editor of the Presbyterian Quarterly and the Presbyterian Standard and moderator of the General Assembly of his church in 1892. He wrote !e Gospel as Taught by Calvin, A Historical Sketch of the Presbyterian Church in the United States, and What Is the Kingdom of God? , as well as his major history of Presbyterianism and numerous articles. As his publications indicate, Reed was an active churchman. While a professor at the seminary in Columbia, South Carolina, he decried the higher critical approach to the Old Testament popular in some American institutions. Reed warned that the in*uence of critical hypotheses about the composition of the Bible would lead to a loss of con+dence in its divine authority. As a contributor to the Presbyterian Standard , the professor vig- orously defended the historic Reformed commitment to the supremacy of Scripture and opposed the contentions of Charles Darwin, which he found incompatible with the teaching of Christianity.