Elspeth Buchan and the Buchanite Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

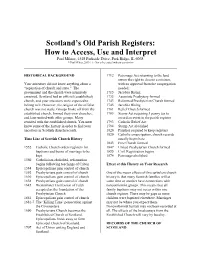

Scotland's Old Parish Registers: How to Access, Use and Interpret

Scotland’s Old Parish Registers: How to Access, Use and Interpret Paul Milner, 1548 Parkside Drive, Park Ridge, IL 6068 © Paul Milner, 2003-11 - Not to be copied without permission HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1712 Patronage Act returning to the land owner the right to choose a minister, Your ancestors did not know anything about a with no approval from the congregation “separation of church and state.” The needed. government and the church were intimately 1715 Jacobite Rising entwined. Scotland had an official (established) 1733 Associate Presbytery formed church, and your ancestors were expected to 1743 Reformed Presbyterian Church formed belong to it. However, the religion of the official 1745 Jacobite Rising church was not static. Groups broke off from the 1761 Relief Church formed established church, formed their own churches, 1783 Stamp Act requiring 3 penny tax to and later united with other groups. Many record an event in the parish register reunited with the established church. You must 1793 Catholic Relief Act know some of the history in order to find your 1794 Stamp Act abolished ancestors in Scottish church records. 1820 Parishes required to keep registers 1829 Catholic emancipation, church records Time Line of Scottish Church History usually begin here 1843 Free Church formed 1552 Catholic Church orders registers for 1847 United Presbyterian Church formed baptisms and banns of marriage to be 1855 Civil Registration begins kept 1874 Patronage abolished 1560 Catholicism abolished, reformation begins following teachings of Calvin Effect of this History on Your Research 1584 Episcopalians gain control of church 1592 Presbyterians gain control of church One of the major effects of this turbulent church 1610 Episcopalians gain control of church history is that many Scottish families will at 1638 Presbyterians gain control of church some time or another have connections with 1645 Westminster Confession of Faith nonconformist groups. -

A Singular Solace: an Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000

A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 David William Dutton BA, MTh October 2020 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Stirling for the degree of Master of Philosophy in History. Division of History and Politics 1 Research Degree Thesis Submission Candidates should prepare their thesis in line with the code of practice. Candidates should complete and submit this form, along with a soft bound copy of their thesis for each examiner, to: Student Services Hub, 2A1 Cottrell Building, or to [email protected]. Candidate’s Full Name: DAVID WILLIAM DUTTON Student ID: 2644948 Thesis Word Count: 49,936 Maximum word limits include appendices but exclude footnotes and bibliographies. Please tick the appropriate box MPhil 50,000 words (approx. 150 pages) PhD 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by publication) 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by practice) 40,000 words (approx. 120 pages) Doctor of Applied Social Research 60,000 words (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Business Administration 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Education 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Midwifery / Nursing / Professional Health Studies 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Diplomacy 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Thesis Title: A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 Declaration I wish to submit the thesis detailed above in according with the University of Stirling research degree regulations. I declare that the thesis embodies the results of my own research and was composed by me. Where appropriate I have acknowledged the nature and extent of work carried out in collaboration with others included in the thesis. -

History of the Presbyterian Churches of the World, Adapted for Use in the Class Room

History of the Presbyterian Churches of the World Adapted for use in the Class Room BY R. C. REED D. D. Professor of Church History in the Presbyterian Theological Seminary at Columbia, South Carolina; author of •• The Gospel as Taught by Calvin." PHILADELPHIA Zbe TKIlestminster press 1912 BK ^71768 Copyright. 1905, by The Trustees of the I'resbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-School Work. Contents CHAPTER PAGE I INTRODUCTION I II SWITZERLAND 14 III FRANCE 34 IV THE NETHERLANDS 72 V AUSTRIA — BOHEMIA AND MORAVIA . 104 VI SCOTLAND 126 VII IRELAND 173 VIII ENGLAND AND WALES 205 IX THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA . 232 X UNITED STATES (Continued) 269 XI UNITED STATES (Continued) 289 XII UNITED STATES (Continued) 301 XIII UNITED STATES (Continued) 313 XIV UNITED STATES (Continued) 325 • XV CANADA 341 XVI BRITISH COLONIAL CHURCHES .... 357 XVII MISSIONARY TERRITORY 373 APPENDIX 389 INDEX 405 iii History of the Presbyterian Churches CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION WRITERS sometimes use the term Presbyterian to cover three distinct things, government, doctrine and worship ; sometimes to cover doctrine and government. It should be restricted to one thing, namely, Church Government. While it is usually found associated with the Calvinistic system of doctrine, yet this is not necessarily so ; nor is it, indeed, as a matter of fact, always so. Presbyterianism and Calvinism seem to have an affinity for one another, but they are not so closely related as to be essential to each other. They can, and occasionally do, live apart. Calvinism is found in the creeds of other than Presby terian churches ; and Presbyterianism is found professing other doctrines than Calvinism. -

The Interaction of Scottish and English Evangelicals

THE INTERACTION OF SCOTTISH AND ENGLISH EVANGELICALS 1790 - 1810 Dudley Reeves M. Litt. University of Glasgov 1973 ProQuest Number: 11017971 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11017971 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to the following: The Rev. Ian A. Muirhead, M.A., B.D. and the Rev. Garin D. White, B.A., B.D., Ph.D. for their most valuable guidance and criticism; My wife and daughters for their persevering patience and tolerance The staff of several libraries for their helpful efficiency: James Watt, Greenock; Public Central, Greenock; Bridge of Weir Public; Trinity College, Glasgow; Baptist Theological College, Glasgow; University of Glasgow; Mitchell, Glasgow; New College, Edinburgh; National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh; General Register House, Edinburgh; British Museum, London; Sion College, London; Dr Williams's, London. Abbreviations British and Foreign Bible Society Baptist Missionary Society Church Missionary Society London Missionary Society Ii§I I Ii§I Society for Propagating the Gospel at Home SSPCK Scottish Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge CONTENTS 1. -

University of Glasgow June 1974

Church and State in the Free Church of. Scotland between 1843 - 1873 Ulrich Dietrich Master of Theology University of Glasgow Department of Ecclesiastical Iiistory June 1974 13 t, C 'es o py Available Variable Print Quality -I- Table of Contents 0 Abbreviations List of Tables Bibliography 92 IV Acknowledgements xi Summary xii The Situation of the Church The Relation between Church and State until 1733 1 The Secession Church of 1733 2 The Burghers and Anti-Burghers of 1747 3 The influence of the French Revolution 4 The Old and New Light Controversy 5 The Revival of Evangelicalism 6 The Voluntary Controversy The Situation in 1829 8 Rev. A. Marshall"s Sermon 11 Duncan Maclaren 12 The Reaction of the Establishment 14 Thomas Chalmers Views on Establishment 19 The Ten Years' Conflict Patronage 26 The Acts of the General Assembly of 1834 29 The Auchtcrarder Case 30 The Marnoch Case 37 The Stewarton Case 41 The Attempts of the General Assembly to solve the Problem 45 Claim of Riaht and Protest of 1843 51 The New Formula The 54 Chances0 - ii - The Principles of the Free Church 57 The "General Principle" 59 William Cunningham 60 The Cardross Case 63 The Resolution of 1857 67 The Union Negotiations 1863 - 1873 The First Year 69 1864 - 1367 79 The Rise of the OppositjLon 91 The Final Stage 98 The Discussion outside the General Assembly of the Free Church The Anti-Union Pamphlets 102 '"he Union Pamphlets 108 The Public Reaction "The Watchword" and "The Presbyterian" 110 The Newspapers 113 Conclusion 130 Appendix I: Biographical Notes 136 141 Appendix II: The Voting Lists 142 'Appendix III: The Burgess Oath Acts of the General Assemblies of the Church of Scotland and the Free Church 142 - III - Abbreviations E. -

Parishes and Congregations: Names No Longer in Use

S E C T I O N 9 A Parishes and Congregations: names no longer in use The following list updates and corrects the ‘Index of Discontinued Parish and Congregational Names’ in the previous online section of the Year Book. As before, it lists the parishes of the Church of Scotland and the congregations of the United Presbyterian Church (and its constituent denominations), the Free Church (1843–1900) and the United Free Church (1900–29) whose names have completely disappeared, largely as a consequence of union. This list is not intended to be ‘a comprehensive guide to readjustment in the Church of Scotland’. Its purpose is to assist those who are trying to identify the present-day successor of a former parish or congregation whose name is now wholly out of use and which can therefore no longer be easily traced. Where the former name has not disappeared completely, and the whereabouts of the former parish or congregation may therefore be easily established by reference to the name of some existing parish, the former name has not been included in this list. Present-day names, in the right-hand column of this list, may be found in the ‘Index of Parishes and Places’ near the end of the book. The following examples will illustrate some of the criteria used to determine whether a name should be included or not: • Where all the former congregations in a town have been united into one, as in the case of Melrose or Selkirk, the names of these former congregations have not been included; but in the case of towns with more than one congregation, such as Galashiels or Hawick, the names of the various constituent congregations are listed. -

June 1987 Department of Theology and Church History Q Kenneth G

HOLY COMMUNION IN THE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY A Thesis submitted to the University of Glasgow for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy KENNETH GRANT HUGHES IFaculty of Divinity, June 1987 Department of Theology and Church History Q Kenneth G. Hughes 1987 i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to record my indebtedness to the late Rev. Ian A. Muirhead, M. A., B. D., formerly lecturer in the Department of Ecclesiastical History in the University of Glasgow, who guided my initial studies relating to the subject of this thesis. I am particularly conscious, also, of my special debt to his successor, Dr. Gavin White, who accepted me as one of his research students without demur and willingly gave time and consideration in guiding the direction of my writing and advising me in the most fruitful deployment of the in- formation at my disposal. The staff of the University Library, Glasgow, have been unfailingly helpful as have the staff of the Library of New College, Edinburgh. Mr. Ian Hope and Miss Joyce Barrie of that Library have particularly gone out of their way to assist in my search for elusive material. I spent a brief period in Germany searching for docu- mentary evidence of Scottish-students of divinity who matric- ulated at the universities of Germany and, again, I wish to acknowledge the help given to me by the Librarians and their staffs at the University Libraries of Heidelberg and Ttbingen. My written enquiries to Halle, Erlangen, Marburg, Giessen, G6ttingen and Rostock met with a most courteous response, though only a small amount of the interesting material they provided was of use in this present study. -

Evangelicalism in Modern Scotland

EVANGELICALISM IN MODERN SCOTLAND D.W. BEBBINGTON, UNIVERSITY OF STIRLING Evangelicals can usefully be defined in terms of four characteristics. First, they are conversionist, believing that lives need to be changed by the gospel. Secondly, they are activist, holding that Christians must spread the gospel. Thirdly, they are biblicist, seeing the Bible as the authoritative source of the gospel. Fourthly, they are crucicentric in their beliefs, recognising in the atonement the focus of the gospel. Three of these four defining qualities marked Protestants in Scotland, as elsewhere, from the Reformation onwards. They were conversionist, biblicist and crucicentric. Seventeenth-century Protestants, however, were not activist in the manner of later Evangelicals. Typically they wrestled with doubts and fears about their own salvation rather than confidently announcing the way of salvation to those outside their sphere. Hence, for instance, there was a remarkable paucity of Protestant missionary work during the seventeenth century. But from the eighteenth century onwards an Evangelical movement sprang into existence in Scotland and elsewhere in the English-speaking world. Its activism marked it out from the Protestant tradition that had preceded it. Evangelicalism was a creation of the eighteenth century. The customary view of the Church of Scotland in the eighteenth century divides it into two parties. The Moderates are usually described as liberal in theology, scholarly in disposition and strongly attached to patronage. The Popular Party is held to have been conservative in theology, unfavourable to contemporary learning and opposed to patronage. Increasingly, however, it has become apparent that the model does not correspond with reality. Some ministers who were theologically conservative nevertheless favoured patronage. -

CHURCH and STATE in the THOUGHT of ALEXANDER Campbell

/CHURCH AND STATE IN THE THOUGHT OF ALEXANDER CAMPBELl/ by MARK STEPHEN JOY B. A., Central Christian College, 1976 M. A., Eastern New Mexico University, 1983 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of History KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1985 Approved by: LD A11205 1,41354 JV HfS %, CONTENTS c . INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE: CHURCH- STATE RELATIONS IN AMERICA TO THE EVE OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY 10 CHAPTER TWO: ALEXANDER CAMPBELL AND THE RESTORATION MOVEMENT 37 CHAPTER THREE: ALEXANDER CAMPBELL'S VIEWS ON CHURCH- STATE ISSUES 69 CHAPTER FOUR: THE SOURCES OF ALEXANDER CAMPBELL'S THOUGHT ON CHURCH-STATE ISSUES Ill CONCLUSION 133 BIBLIOGRAPHY 140 INTRODUCTION The establishment of constitutional provisions prohibiting the establishment of religion, and guaranteeing the free exercise thereof, was one of the most significant developments in early American history. These first amendment provisions also imply a concept which was, in the eighteenth century, a uniquely American contribution to political theory: the separation of church and state. The incorporation of these principles into the Constitution was not an overnight accomplishment, nor did the passage of the First Amendment mean that the controversies over matters of religious liberty and the relationship of church and state were over. But these developments, coupled with the pluralism that has been a character- istic of American life from the very beginning of colonization, have contributed greatly to the creation of a distinctively American religious tradition. Many scholars have noted that two currents of thought were influential in bringing about the separation of church and state in America. -

Mochrie, Economics of Religion in Smith and Chalmers 1

Discussion Paper 012: Mochrie, Economics of Religion in Smith and Chalmers 1 MODERATES, EVANGELICALS AND THE SCOTTISH CONTRIBUTION TO THE ECONOMICS OF RELIGION PRIOR TO THE DISRUPTION OF 1843 Robert I. Mochrie Accountancy, Economics and Finance, School of Management and Languages, Heriot-Watt University 1 Introduction The development of a recognizable field of the economics of religion has been accompanied by re-examination of the analysis of religious markets in Smith (1776). Anderson (1988) and Ekelund et al. (2005) have claimed that Smith was a supporter of free markets in religion that would maximize consumer sovereignty. Leathers & Raines (1992, 1999, and 2006) have sought to demonstrate that Smith favoured regulation of markets for religion to promote public order. Trying to reconcile these two positions, Witham (2011) reads Ekelund et al. (2005) as claiming that Smith merely advocated certain forms of Establishment – specifically the Presbyterianism of his native Scotland, as practised at the time he was writing – as maximizing consumer sovereignty only where the market for religion is regulated. While it is perhaps possible to think of Smith as writing about religion from the standpoint of an impartial spectator, Leathers & Raines (1999) introduce the contribution of Thomas Chalmers, another Scot who contributed substantially to the development of political economy. From the time of his appointment to the chair of divinity at the University of Edinburgh in 1828, his lectures covered political economy (Chalmers 1832). While historians of economic thought are probably most familiar with Chalmers’ Malthusianism, especially as framed by Waterman (1991a, 1991b, 1993, 1995 and 2006), he spent the later part of the 1830s leading the Church of Scotland’s campaign for additional public endowments; and when that failed, as Leathers & Raines (1999, 2002) note, he took an active part in forming a new denomination, designing and implementing the funding mechanism that ensured its financial stability. -

Presbytery Finding Aid

Falkirk Archives (Archon Code: GB558) FALKIRK ARCHIVES Records of Churches Presbytery finding aid This finding aid details the records held for the presbyteries of various denominations which cover the geographical area of present-day Falkirk presbytery. The predominant form of church government in Scotland since the Reformation has been Presbyterian. Between 1560 and 1690 the form of church government was not settled as church and state struggled to establish agreement but from 1690 under the Act of Settlement the Church of Scotland was firmly Presbyterian in governance. The Presbyterian structure involves governance by a series of church courts. The lowest level is the Kirk Session which governs the work of a single congregation and which is made up of the elders of the congregation and moderated (or convened) by the minister (also known as the teaching elder). Above this is Presbytery, which consists of all the ministers in a geographic area plus at least one elder from each congregation, and on the principle of parity of membership, there are additional elders as counterparts to any ministers without a congregation (such as retired ministers or ministers in chaplaincy or administrative posts). In larger churches there will be up to two further tiers of church courts, typically Synods and then a General Assembly. Some smaller denominations use Synod as the top level court, while others have abolished Synods and use only a General Assembly as the top level court. United Secession Church. Presbytery of Stirling and Falkirk The United Secession Church was formed in 1820 with the union of the New Licht Burghers and the New Licht Anti-Burghers. -

'Hooded Crows'? a Reflection on Scottish Ecclesiastical Dress and Ministerial Practice from the Reformation to the Present D

Transactions of the Burgon Society Volume 13 Article 5 1-1-2013 ‘Hooded crows’? A Reflection on Scottish cclesiasticalE Dress and Ministerial Practice from the Reformation to the Present Day Graham Deans University of St. Andrews Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/burgonsociety Recommended Citation Deans, Graham (2014) "‘Hooded crows’? A Reflection on Scottish cclesiasticalE Dress and Ministerial Practice from the Reformation to the Present Day," Transactions of the Burgon Society: Vol. 13. https://doi.org/10.4148/2475-7799.1109 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Burgon Society by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transactions of the Burgon Society, 13 (2013), pages 45–73 ‘Hooded crows’? A Reflection on Scottish Ecclesiastical Dress and Ministerial Practice from the Reformation to the Present Day By Graham Deans he hooded crow was a species of birds originally described by Carl Linnaeus (1707–78) in his Systema Naturae (1758),1 where he named it corvus cornix.2 The image of the Thooded crow has traditionally been regarded as an unflattering caricature of clergymen in black, while the grey plumage on the bird’s back symbolizes the academic hood. The hood- ed cleric is thought to be something of a rara avis, which perches in a crow’s nest pulpit, from which it emits its distinctive squawking noises, six feet above contradiction! This association has, however, not been confined to Scotland, which is part of the natural habitat of corvus cornix.