On the Verge Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tripadvisor Appoints Lindsay Nelson As President of the Company's Core Experience Business Unit

TripAdvisor Appoints Lindsay Nelson as President of the Company's Core Experience Business Unit October 25, 2018 A recognized leader in digital media, new CoreX president will oversee the TripAdvisor brand, lead content development and scale revenue generating consumer products and features that enhance the travel journey NEEDHAM, Mass., Oct. 25, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- TripAdvisor, the world's largest travel site*, today announced that Lindsay Nelson will join the company as president of TripAdvisor's Core Experience (CoreX) business unit, effective October 30, 2018. In this role, Nelson will oversee the global TripAdvisor platform and brand, helping the nearly half a billion customers that visit TripAdvisor monthly have a better and more inspired travel planning experience. "I'm really excited to have Lindsay join TripAdvisor as the president of Core Experience and welcome her to the TripAdvisor management team," said Stephen Kaufer, CEO and president, TripAdvisor, Inc. "Lindsay is an accomplished executive with an incredible track record of scaling media businesses without sacrificing the integrity of the content important to users, and her skill set will be invaluable as we continue to maintain and grow TripAdvisor's position as a global leader in travel." "When we created the CoreX business unit earlier this year, we were searching for a leader to be the guardian of the traveler's journey across all our offerings – accommodations, air, restaurants and experiences. After a thorough search, we are confident that Lindsay is the right executive with the experience and know-how to enhance the TripAdvisor brand as we evolve to become a more social and personalized offering for our community," added Kaufer. -

A Day in the Life of Your Data

A Day in the Life of Your Data A Father-Daughter Day at the Playground April, 2021 “I believe people are smart and some people want to share more data than other people do. Ask them. Ask them every time. Make them tell you to stop asking them if they get tired of your asking them. Let them know precisely what you’re going to do with their data.” Steve Jobs All Things Digital Conference, 2010 Over the past decade, a large and opaque industry has been amassing increasing amounts of personal data.1,2 A complex ecosystem of websites, apps, social media companies, data brokers, and ad tech firms track users online and offline, harvesting their personal data. This data is pieced together, shared, aggregated, and used in real-time auctions, fueling a $227 billion-a-year industry.1 This occurs every day, as people go about their daily lives, often without their knowledge or permission.3,4 Let’s take a look at what this industry is able to learn about a father and daughter during an otherwise pleasant day at the park. Did you know? Trackers are embedded in Trackers are often embedded Data brokers collect and sell, apps you use every day: the in third-party code that helps license, or otherwise disclose average app has 6 trackers.3 developers build their apps. to third parties the personal The majority of popular Android By including trackers, developers information of particular individ- and iOS apps have embedded also allow third parties to collect uals with whom they do not have trackers.5,6,7 and link data you have shared a direct relationship.3 with them across different apps and with other data that has been collected about you. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

How to Get Started with Zoom - the Verge

8/3/2020 How to get started with Zoom - The Verge HOW-TO REVIEWS TECH 14 How to get started with Zoom You can make a free account right now By Jay Peters @jaypeters Mar 31, 2020, 2:51pm EDT If you buy something from a Verge link, Vox Media may earn a commission. See our ethics statement. Illustration by Alex Castro / The Verge Part of The Verge Guide to staying connected Before the pandemic, many companies were already using the videoconferencing app Zoom for business meetings, interviews, and other purposes. More recently, many individuals facing long days without contact with friends and family have moved to Zoom for face-to-face and group get-togethers. This is a quick guide for those who haven’t tried Zoom yet, featuring tips on how to get started using its free version. One thing to keep in mind: while one-to-one video calls can https://www.theverge.com/2020/3/31/21197215/how-to-zoom-free-account-get-started-register-sign-up-log-in-invite 1/7 8/3/2020 How to get started with Zoom - The Verge go as long as you want, any group calls on Zoom are limited to 40 minutes. If you want to have longer talks without interruption, you can either pay for Zoom’s Pro plan ($14.99 a month) or try an alternative videoconferencing app. (Note: there have been reports that the 40 minutes is sometimes extended — at least one staffer from The Verge found that an evening meeting with five friends was sent an extension when time started running out — but there has been no official word of any change from Zoom.) HOW TO REGISTER FOR ZOOM The first thing to do, of course, is to register for the service. -

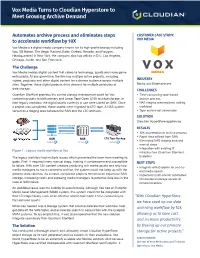

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals. -

Keeping Faith with the Student-Athlete, a Solid Start and a New Beginning for a New Century

August 1999 In light of recent events in intercollegiate athletics, it seems particularly timely to offer this Internet version of the combined reports of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. Together with an Introduction, the combined reports detail the work and recommendations of a blue-ribbon panel convened in 1989 to recommend reforms in the governance of intercollegiate athletics. Three reports, published in 1991, 1992 and 1993, were bound in a print volume summarizing the recommendations as of September 1993. The reports were titled Keeping Faith with the Student-Athlete, A Solid Start and A New Beginning for a New Century. Knight Foundation dissolved the Commission in 1996, but not before the National Collegiate Athletic Association drastically overhauled its governance based on a structure “lifted chapter and verse,” according to a New York Times editorial, from the Commission's recommendations. 1 Introduction By Creed C. Black, President; CEO (1988-1998) In 1989, as a decade of highly visible scandals in college sports drew to a close, the trustees of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation (then known as Knight Foundation) were concerned that athletics abuses threatened the very integrity of higher education. In October of that year, they created a commission on Intercollegiate Athletics and directed it to propose a reform agenda for college sports. As the trustees debated the wisdom of establishing such a commission and the many reasons advanced for doing so, one of them asked me, “What’s the down side of this?” “Worst case,” I responded, “is that we could spend two years and $2 million and wind up with nothing to show of it.” As it turned out, the time ultimately became more than three years and the cost $3 million. -

Elsagate” Phenomenon: Disturbing Children’S Youtube Content and New Frontiers in Children’S Culture

Selected Papers of #AoIR2019: The 20th Annual Conference of the Association of Internet Researchers Brisbane, Australia / 2-5 October 2019 EXAMINING THE “ELSAGATE” PHENOMENON: DISTURBING CHILDREN’S YOUTUBE CONTENT AND NEW FRONTIERS IN CHILDREN’S CULTURE Jessica Balanzategui Swinburne University of Technology Contemporary children are turning to online video streaming as an “alternative for TV” (Ha 2018, 1) in increasing numbers (see Australian Communications and Media Authority 2017, 20-22). In addition, US-based global video streaming platforms, primarily YouTube and Netflix, are becoming “more influential in screen production ecologies” when it comes to children’s content (Potter 2017a, 22). Yet, as increasing numbers of children consume much of their video content outside of the legacy media spaces of film and television, serious concerns are being raised in policy, advocacy (Centre for Digital Democracy, 2018), and journalistic (Bridle, 2017) discussions around the globe because many new children’s video streaming genres are not “child-appropriate” according to extant definitions and guidelines, such as the internationally endorsed Children’s Television Charter. Alarms have been raised in relation to new genres on YouTube in particular. For instance, in an influential journalistic exposé, James Bridle (2017) argues that YouTube content seemingly aimed at child-viewers is tantamount to “a kind of infrastructural violence” against children’s wellbeing, a point echoed in many other recent long-form journalistic investigations (see for instance Orphanides 2018). Public concerns about the strange approach to children’s content exhibited by various YouTube genres have become so prevalent that the neologism “Elsagate” is now commonly used in media reportage to describe the scandal. -

The History of the Ipad

Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association Volume 2015 Article 3 2016 The iH story of the iPad Michael Scully Roger Williams University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Scully, Michael (2016) "The iH story of the iPad," Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association: Vol. 2015 , Article 3. Available at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings/vol2015/iss1/3 This Conference Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association by an authorized editor of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The iH story of the iPad Cover Page Footnote Thank you to Roger Williams University and Salve Regina University. This conference paper is available in Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association: http://docs.rwu.edu/ nyscaproceedings/vol2015/iss1/3 Scully: iPad History The History of the iPad Michael Scully Roger Williams University __________________________________________________________________ The purpose of this paper is to review the history of the iPad and its influence over contemporary computing. Although the iPad is relatively new, the tablet computer is having a long and lasting affect on how we communicate. With this essay, I attempt to review the technologies that emerged and converged to create the tablet computer. Of course, Apple and its iPad are at the center of this new computing movement. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ORR PARTNERS ENGAGED BY VOX MEDIA Reston, VA (January 12, 2016) — Vox Media has selected Orr Partners to manage the expansion of their 1201 Connecticut Avenue office in Washington, DC. The modern media company will utilize the additional space to accommodate the rapid growth of its major brands. The improvements include: • Seating for approximately 100 staff • Recording facilities • Conference and teaming areas • Ancillary / teaming space “We are excited we were selected for this exciting and challenging project,” commented Scott Siegel, President of Orr Partners. “We appreciate Vox’s confidence in our team.” The project will commence immediately with assembly of the full project team and completion of the design. “Vox has a great energy about them,” stated Clif White, Senior Project Manager for Orr Partners. “I look forward to working closely with the project team to deliver a project we will all be proud of.” The project will deliver in spring of 2016. ABOUT ORR PARTNERS Orr Partners, an award-winning Project Management firm in Reston, Virginia, is a leading provider of owner's representation services. Specializing in complex project management, Orr Partners provides services for a diverse client base in multiple disciplines including corporate tenant improvements, multi-family, educational, religious, industrial, healthcare, manufacturing, and public sector work. For more detailed information, please email [email protected], visit orrpartners.com or call Scott Siegel at 703-289-2132. For more information on Orr’s property management business, MacGregor Property Management, visit magregorpm.com. For more information on Orr’s safety and QA/QC business, NSBI, visit nsbuilding.com. -

Education on the Verge: Annual Meeting Program

ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM EDUCATION ON THE VERGE: 101ST ANNUAL MEETING Driving Student Success Initiatives in Higher Education April 12-15, 2015 Baltimore Convention Center Baltimore, Maryland www.aacrao.org 131129_AACRAO_101st-Cover.indd 1 2/24/14 1:26 PM 100th Annual Meeting Welcome Letter . 2 Meeting at a Glance . 38 Sponsors . 5 Saturday Events and Workshops . 42 Room Locations . 6 Sunday Events and Workshops . 43 Annual Meeting Notes and Reminders . 8 Monday Events and Sessions . 48 AACRAO Registration Area . 9 Tuesday Events and Sessions . 68 Map of Nearby Hotels . 10 Wednesday Events and Sessions . 86 Convention Center Floor Plans . .11 Upcoming Events . 97 2013-2014 Board of Directors . .17 Exhibitor Floor Plan . 100 2014 Annual Meeting Committees . .17 Exhibitor List and Booth Number . 101 Past Annual Meetings . 18 Exhibitors and Contacts . 103 2014 Award Winners . 20 Exhibitor Products and Services . 118 Past Award Winners . 25 Plenary Speakers . 31 Luncheon Speaker . 32 General Session Featured Speakers . 33 THE PRECIPICE OF CHANGE 1 Welcome to Denver “Education on the Verge: The Precipice of Change” Dear Colleague, On behalf of AACRAO, we are delighted to welcome you to our 100th Annual Meeting in Denver! With today’s colleges and universities facing opportunities and challenges that did not exist just a decade ago, we remain committed to expanding the scope and breadth of our programmatic offerings to meet this changing landscape. From the expanding global scale of higher education, to the growing presence of social media and its many uses in recruitment and retention, coupled with the need to quickly adapt to rapidly evolving technology and innovation on our campuses, higher education administrators are operating in a highly dynamic environment. -

Tech Blog Spinoff Re/Code Is Acquired by Online Media Chain 27 May 2015, Bythe Associated Press

Tech blog spinoff Re/code is acquired by online media chain 27 May 2015, byThe Associated Press Tech news blog Re/code said Tuesday it's been acquired by online publishing company Vox Media, just 18 months after spinning off from its former parent, The Wall Street Journal. Vox operates several news and entertainment sites, including The Verge, which also covers tech news. In an online statement, Re/code founders Kara Swisher and Walt Mossberg said they will continue to operate their site separately but may occasionally collaborate with The Verge. Re/code has focused on tech companies and business news, while The Verge reports from a culture and lifestyle perspective. Terms of the acquisition were not disclosed. Swisher and Mossberg started their blog at The Wall Street Journal, which is owned by News Corp., where it was known as AllThingsD. Since the spinoff, Re/code has continued to stage successful industry conferences and earned a reputation for breaking exclusive stories. But its readership has lagged. Re/code had 1.5 million unique visitors in April, compared with 12 million for the Verge and 53 million for all Vox sites combined, according to the comScore research service. Another tech news site, GigaOm, shut down earlier this year. A number of other news sites continue to cover the tech industry in New York and Silicon Valley, and some have added staff in recent months. © 2015 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. APA citation: Tech blog spinoff Re/code is acquired by online media chain (2015, May 27) retrieved 25 September 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2015-05-tech-blog-spinoff-recode-online.html This document is subject to copyright. -

How to Be an Editor Spring 2020 Jennifer Kahn [email protected]

How to Be an Editor Spring 2020 Jennifer Kahn [email protected] (510) 861-6654 Class time: Thursdays 3-6pm. Location: Greenhouse (room 209), North Gate Hall Office hours: Thursdays 6-7pm, or by appointment This course is designed to be a tasting platter for the aspiring print or online editor, or anyone curious about the job. It’s also a great course for writers who want to learn how editors think, and use those skills to make their own work better. Almost anyone can read a piece and tell that it isn’t working. But identifying precisely why it isn’t working and how to fix it is magic. (Unlike most writing jobs, editorial jobs also come with salaries and benefits. So there’s that.) One goal of this class will be to connect you with actual working editors at great publications. Over the semester, we’ll host or hear from editors at the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, California Sunday, The Atlantic, The New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, Mother Jones, and more. We’ll also be doing the occasional field trip, beginning with one to Wired Magazine. Beyond building a network of career connections, these visits are designed to prepare you for a job in the editing world through real-world practice. Editors applying for a job at a publication are typically asked to take an editing test. Through our guests, we’ll get actual samples of these, and work through them – then have the results critiqued by a real editor in charge of hiring.