Elsagate” Phenomenon: Disturbing Children’S Youtube Content and New Frontiers in Children’S Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

Disturbed Youtube for Kids: Characterizing and Detecting Inappropriate Videos Targeting Young Children

Proceedings of the Fourteenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2020) Disturbed YouTube for Kids: Characterizing and Detecting Inappropriate Videos Targeting Young Children Kostantinos Papadamou, Antonis Papasavva, Savvas Zannettou,∗ Jeremy Blackburn,† Nicolas Kourtellis,‡ Ilias Leontiadis,‡ Gianluca Stringhini, Michael Sirivianos Cyprus University of Technology, ∗Max-Planck-Institut fur¨ Informatik, †Binghamton University, ‡Telefonica Research, Boston University {ck.papadamou, as.papasavva}@edu.cut.ac.cy, [email protected], [email protected] {nicolas.kourtellis, ilias.leontiadis}@telefonica.com, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract A large number of the most-subscribed YouTube channels tar- get children of very young age. Hundreds of toddler-oriented channels on YouTube feature inoffensive, well produced, and educational videos. Unfortunately, inappropriate content that targets this demographic is also common. YouTube’s algo- rithmic recommendation system regrettably suggests inap- propriate content because some of it mimics or is derived Figure 1: Examples of disturbing videos, i.e. inappropriate from otherwise appropriate content. Considering the risk for early childhood development, and an increasing trend in tod- videos that target toddlers. dler’s consumption of YouTube media, this is a worrisome problem. In this work, we build a classifier able to discern inappropriate content that targets toddlers on YouTube with Frozen, Mickey Mouse, etc., combined with disturbing con- 84.3% accuracy, and leverage it to perform a large-scale, tent containing, for example, mild violence and sexual con- quantitative characterization that reveals some of the risks of notations. These disturbing videos usually include an inno- YouTube media consumption by young children. Our analy- cent thumbnail aiming at tricking the toddlers and their cus- sis reveals that YouTube is still plagued by such disturbing todians. -

"Youtube Kids" – Another Door Opener for Pedophilia?

Online link: www.kla.tv/12561 | Published: 08.06.2018 "YouTube Kids" – another door opener for Pedophilia? „Elsagate“: With the App „You Tube-Kids”, You Tube offers a service that is supposed to help parents to protect their children from inappropriate contents. However, while parents think they are safe, children are confronted with brutal videos including scenes of violence, perverse sex fantasies and cannibalism. These disturbing contents are staged by characters like Ice Queen "Elsa, “Spiderman” or “Mickey Mouse”. Is “YouTube-Kids” being abused as door-opener to make children receptive to abhorrent practices and pedophilia “socially acceptable”? Since 2015 YouTube has been offering a service with the App "YouTube Kids" to help parents and children to receive only those video-clips in the proposal bar that are child and family friendly. An algorithm (that is a method of calculation) takes over the function of filtering the content that is unsuitable for children. The App has been installed more than 60 million times and is available in 37 countries and eight languages – since September 2017 also in Germany. Unfortunately, this App – that promises safety for children – however, is in no way as reliable as many parents wish it was. On the contrary: it is even dangerous. Already since June 2016 media reports have increased that children are confronted with a number of brutal children's series and animated videos that – beyond any morality – convey extremely repulsive content and that are filled with topics that are in no way suitable for children. It's about violence scenes, perverse sex fantasies or cannibalism. -

Audio-Visual Genres and Polymediation in Successful Spanish Youtubers †,‡

future internet Article Audio-Visual Genres and Polymediation in Successful Spanish YouTubers †,‡ Lorenzo J. Torres Hortelano Department of Sciences of Communication, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, 28943 Fuenlabrada, Madrid, Spain; [email protected]; Tel.: +34-914888445 † This paper is dedicated to our colleague in INFOCENT, Javier López Villanueva, who died on 31 December 2018 during the finalization of this article, RIP. ‡ A short version of this article was presented as “Populism, Media, Politics, and Immigration in a Globalized World”, in Proceedings of the 13th Global Communication Association Conference Rey Juan Carlos University, Madrid, Spain, 17–19 May 2018. Received: 8 January 2019; Accepted: 2 February 2019; Published: 11 February 2019 Abstract: This paper is part of broader research entitled “Analysis of the YouTuber Phenomenon in Spain: An Exploration to Identify the Vectors of Change in the Audio-Visual Market”. My main objective was to determine the predominant audio-visual genres among the 10 most influential Spanish YouTubers in 2018. Using a quantitative extrapolation method, I extracted these data from SocialBlade, an independent website, whose main objective is to track YouTube statistics. Other secondary objectives in this research were to analyze: (1) Gender visualization, (2) the originality of these YouTube audio-visual genres with respect to others, and (3) to answer the question as to whether YouTube channels form a new audio-visual genre. I quantitatively analyzed these data to determine how these genres are influenced by the presence of polymediation as an integrated communicative environment working in relational terms with other media. My conclusion is that we can talk about a new audio-visual genre. -

Tripadvisor Appoints Lindsay Nelson As President of the Company's Core Experience Business Unit

TripAdvisor Appoints Lindsay Nelson as President of the Company's Core Experience Business Unit October 25, 2018 A recognized leader in digital media, new CoreX president will oversee the TripAdvisor brand, lead content development and scale revenue generating consumer products and features that enhance the travel journey NEEDHAM, Mass., Oct. 25, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- TripAdvisor, the world's largest travel site*, today announced that Lindsay Nelson will join the company as president of TripAdvisor's Core Experience (CoreX) business unit, effective October 30, 2018. In this role, Nelson will oversee the global TripAdvisor platform and brand, helping the nearly half a billion customers that visit TripAdvisor monthly have a better and more inspired travel planning experience. "I'm really excited to have Lindsay join TripAdvisor as the president of Core Experience and welcome her to the TripAdvisor management team," said Stephen Kaufer, CEO and president, TripAdvisor, Inc. "Lindsay is an accomplished executive with an incredible track record of scaling media businesses without sacrificing the integrity of the content important to users, and her skill set will be invaluable as we continue to maintain and grow TripAdvisor's position as a global leader in travel." "When we created the CoreX business unit earlier this year, we were searching for a leader to be the guardian of the traveler's journey across all our offerings – accommodations, air, restaurants and experiences. After a thorough search, we are confident that Lindsay is the right executive with the experience and know-how to enhance the TripAdvisor brand as we evolve to become a more social and personalized offering for our community," added Kaufer. -

A Day in the Life of Your Data

A Day in the Life of Your Data A Father-Daughter Day at the Playground April, 2021 “I believe people are smart and some people want to share more data than other people do. Ask them. Ask them every time. Make them tell you to stop asking them if they get tired of your asking them. Let them know precisely what you’re going to do with their data.” Steve Jobs All Things Digital Conference, 2010 Over the past decade, a large and opaque industry has been amassing increasing amounts of personal data.1,2 A complex ecosystem of websites, apps, social media companies, data brokers, and ad tech firms track users online and offline, harvesting their personal data. This data is pieced together, shared, aggregated, and used in real-time auctions, fueling a $227 billion-a-year industry.1 This occurs every day, as people go about their daily lives, often without their knowledge or permission.3,4 Let’s take a look at what this industry is able to learn about a father and daughter during an otherwise pleasant day at the park. Did you know? Trackers are embedded in Trackers are often embedded Data brokers collect and sell, apps you use every day: the in third-party code that helps license, or otherwise disclose average app has 6 trackers.3 developers build their apps. to third parties the personal The majority of popular Android By including trackers, developers information of particular individ- and iOS apps have embedded also allow third parties to collect uals with whom they do not have trackers.5,6,7 and link data you have shared a direct relationship.3 with them across different apps and with other data that has been collected about you. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

How to Get Started with Zoom - the Verge

8/3/2020 How to get started with Zoom - The Verge HOW-TO REVIEWS TECH 14 How to get started with Zoom You can make a free account right now By Jay Peters @jaypeters Mar 31, 2020, 2:51pm EDT If you buy something from a Verge link, Vox Media may earn a commission. See our ethics statement. Illustration by Alex Castro / The Verge Part of The Verge Guide to staying connected Before the pandemic, many companies were already using the videoconferencing app Zoom for business meetings, interviews, and other purposes. More recently, many individuals facing long days without contact with friends and family have moved to Zoom for face-to-face and group get-togethers. This is a quick guide for those who haven’t tried Zoom yet, featuring tips on how to get started using its free version. One thing to keep in mind: while one-to-one video calls can https://www.theverge.com/2020/3/31/21197215/how-to-zoom-free-account-get-started-register-sign-up-log-in-invite 1/7 8/3/2020 How to get started with Zoom - The Verge go as long as you want, any group calls on Zoom are limited to 40 minutes. If you want to have longer talks without interruption, you can either pay for Zoom’s Pro plan ($14.99 a month) or try an alternative videoconferencing app. (Note: there have been reports that the 40 minutes is sometimes extended — at least one staffer from The Verge found that an evening meeting with five friends was sent an extension when time started running out — but there has been no official word of any change from Zoom.) HOW TO REGISTER FOR ZOOM The first thing to do, of course, is to register for the service. -

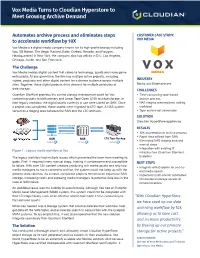

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals. -

Youtube Kids: Parent’S Guide

YouTube Kids: parent’s guide YouTube Kids launched in the UK in November 2015 as a service suitable for younger children with age-appropriate content. As of April 2018, it has gone under some major changes. What do you need to know about YouTube Kids? What is YouTube Kids? YouTube Kids is an app developed by YouTube aimed at delivering age-appropriate content to young children. The app is available on Android, iOS and some Smart TVs. Until recently, the content that appeared on the app was predominantly curated by computer-algorithms and essentially the app was a filtered version of the regular body of videos available on YouTube. However, the app will now have some human curation, by the YouTube Kids team, and allow for greater parental control. What type of content can you expect to find on YouTube Kids? YouTube Kids offers free-to-watch content. This content is made freely available by having advertisements run before videos. Content on YouTube Kids ranges from cartoons to nursery rhymes and from toys reviews to music videos. Currently, the channel with the greatest number of subscribers, 16.8 million, on YouTube Kids is “ChuChu TV Nursery Rhymes and Kids Songs” which produces animated versions of popular children’s rhymes as well as its own songs and educational videos. The second most subscribed channel, with 15 million subscribers, is LittleBabyBum which is another channel centered on animated nursery rhymes. YouTube Kids also offers a paid for service called YouTube Red. This allows children to watch original content produced by YouTube as well as seasons of cartoon favourites such as Postman Pat. -

A Critical Reading of Gender Roles in Frozen, Zootopia, Despicable Me and Minions

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 6 ~ Issue 12 (2018)pp.:11-15 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Pixelating Gender: A Critical Reading of Gender Roles in Frozen, Zootopia, Despicable Me and Minions. Lakshmi P.Gopal 1(Assistant Professor on contract) 2(Department of English, St. Aloysius College, Edathua) ABSTRACT: Animation films are cultural products that exist in the cultural domain for a significant period in the form of prequels, sequels, series and adaptations into different languages. The tremendous impact it has on coming generation calls for a critical reading of the gendered notions presented in this novel media form. A critical reading of the gender roles presented by Disney Studios and Illumination Entertainment Studios shows howthe objective of positive representation is a distant dream. Received 02 December, 2018; Accepted 08 December, 2018 © The Author(S) 2018. Published With Open Access At www.Questjournals.Org. I. INTRODUCTION Movies are the popularliterature of our time. Film studies with respect to gender studies have already gained momentum with the publication of seminal texts such as Popcorn Venusby Marjorie Rosen, From Reverence to Rape by Molly Haskell, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” by Laura Mulvey and through insightful studies by Mary Ann Doane. Gender Studies as it is now is a field of interdisciplinary study devoted to the studyof gender identity and gendered representation as categories of analysis. It also engages in studying the intersection of gender with other categories of analysis of identity including race, sexuality, class, disability and nationality.Though theories regarding post-feminist approaches are in vogue, the very need of a feminist reading of films with a focus on gender still has atremendous scope,as the critical research in thearea associated still hasn‟t achieved its objectives in representing awoman in a non-stereotypical, non-objectified role. -

Into the Unknown & Let It

Into the Unknown & Let it Go! Frozen Medley Into the Unknown The first section of the medley is focussed on ‘Into the Unknown’ from Frozen 2. The song was written by Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez, who also wrote the music for the original Frozen film. The song is performed by Idina Menzel who is the voice of Elsa, and Aurora who is singer from Norway. Into the Unknown Into the Unknown is Elsa’s main song in the whole film. Throughout the song there is a mysterious voice that Elsa doesn’t understand at this point. She later finds that it is a siren call, calling out to her. The siren call is the ’Aahhh Aahhh’ part! The siren call is in the style of a Scandinavian form of music called kulning. Kulning Challenge! Kulning is used in both Sweden and Norway and is often used to call livestock (cows, goats, etc.) down from high mountain pastures where they have been grazing during the day. It is possible that the sound also serves to scare away predators but this is not the main purpose of the call. The call is high pitched and always starts by using your head voice and then moves up and down in small steps. Sometimes it can sound quite sad or haunting but the main aim is for the call to communicate over a long distance! Your challenge is to create your own kulning call and have a go at singing it outdoors! Into the Unknown & Let it Go Into the Unknown is based on Elsa's inner conflict over deciding whether or not to leave Arendelle and track down the source of a mysterious voice she keeps hearing.