GENERAL AGREEMENT on RESTRICTED C/RM/M/8 8 October 1990 TARIFFS and TRADE Limited Distribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2013 Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit Caitlin Rickert Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Health Communication Commons Recommended Citation Rickert, Caitlin, "Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit" (2013). Master's Theses. 136. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/136 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT by Caitlin Rickert A Thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Communication Western Michigan University April 2013 Thesis Committee: Heather Addison, Ph. D., Chair Sandra Borden, Ph. D. Joseph Kayany, Ph. D. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT Caitlin Rickert, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2013 This study explores how The Biggest Loser, a popular television reality program that features a weight-loss competition, reflects and magnifies established stereotypes about obese individuals. The show, which encourages contestants to lose weight at a rapid pace, constructs a broken/fixed dichotomy that oversimplifies the complex issues of obesity and health. My research is a semiotic analysis of the eleventh season of the program (2011), focusing on three pairs of contestants (or “couples” teams) that each represent a different level of commitment to the program’s values. -

Rock for Beginners – Miguel Amorós

Rock for Beginners – Miguel Amorós Shake, Rattle and Roll “Rock”, properly speaking, refers to a particular musical style created by Anglo-Saxon youth culture that spread like wildfire to every country where the modern conditions of production and consumption had reached a certain qualitative threshold, that is, where capitalism had given rise to a mass society of socially uprooted individuals. The phenomenon first took shape after World War Two in the United States, the most highly developed capitalist country, and then spread to England; from there it returned like a boomerang to the country of its origin, irradiating its influence everywhere, changing people’s lives in different ways. To get a better understanding of rock, we will first have to review the concepts of subculture, music and youth. The word “subculture” refers to the behaviors, values, jargons and symbols of a separate milieu—ethnic, geographic, sexual or religious—within the dominant culture, which was, and still is, of course, the culture of the ruling class. Beginning in the sixties, once the separation was imposed from above between elite culture, reserved for the leaders, and mass culture, created to regiment the led, to coarsen their tastes and brutalize their senses—between high culture and masscult,1 as Dwight McDonald called them—the term would be used to refer to alternative consumerist lifestyles, which were reflected in various ways in the music that was at first called “modern” music, and then pop music. The mechanism of identification that produced youth subculture was ephemeral, since it was constantly being offset by the temporary character of youth. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Rich Dad Poor

Rich Dad Poor Dad will… • Explode the myth that you need to earn a high income to become rich • Challenge the belief that your house is an asset • Show parents why they can’t rely on the school system to teach their kids about money • Define once and for all an asset and a liability • Teach you what to teach your kids about money for their future financial success Robert Kiyosaki has challenged and changed the way tens of millions of people around the world think about money. With perspectives that often contradict conventional wisdom, Robert has earned a reputation for straight talk, irreverence and courage. He is regarded worldwide as a passionate advocate for financial education. R o b What The Rich Teach Their Kids About Money – “The main reason people struggle financially is because they e That The Poor And Middle Class Do Not! have spent years in school but learned nothing about money. r The result is that people learn to work for money… but never t learn to have money work for them.” T . – Robert Kiyosaki K i y Rich Dad Poor Dad – The #1 Personal Finance Book of All Time! o “Rich Dad Poor Dad is a starting point for anyone looking to gain control of their s financial future.” – USA TODAY a k i www.richdad.com ™ $16.95 US | $19.95 CAN Robert T. Kiyosaki “Rich Dad Poor Dad is a starting point for anyone looking to gain control of their financial future.” – USA TODAY RICH DAD POOR DAD What The Rich Teach Their Kids About Money— That The Poor And Middle Class Do Not! By Robert T. -

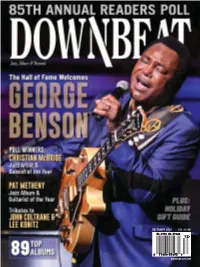

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Lionel Hompton # Jozz Fes'tivol '"?Iæfy O '- C) O

{ I !t i ; I I I i 1 I l Ë I I i I I i I Lionel Hompton # Jozz Fes'tivol '"?iÆFY o '- c) o =o- o ! p o C f ol o-- (I) Dr. lionel Hampton, producer *rJ assisted by Dr. lynn J. Skinner Welcome to the 3lst University of Idaho Lionel HamptonJazzÏestival! The Lionel HárirptonJazzEestivalhas become one of the greatest jzzzfestivals in the world. join Pleæe us in celebratin g a clæsically American art form - Iazz. At the Lionel HamptonJazzEestivalwe seek to enrich the lives of young people with this music - year after year. "GAtes" Keeps on Swingin' Lionel Hampton started his musicalcareer æ a drummer. Hamp wæ playing drums with Louie Armstrong and one night at the gig, Louie turned to Hamp and said, "Swing it Gates, Swing!" Hamp asked Louie what he meantand he said, "l'm calling you Gates because you swing like a gatel" From that point in time until this very day Hamp is known as "Gates" because of his incredible ability to "swing". The story came to Dr. Skinner directly from Hamp. 1 I Welcome to the 1998 Jazz Festival atthe University of Idaho - Moscow, Idaho! Page For more informoÌion concerning the Concert Schedule Lionel Homplon Jozz Feslivol, contoct: 5 Lionel Hampton School of MusicJøz Ensembles 11 Dr. Lynn J. Skinner, Execulive Direclor Welcome Letters 13 Lionel Homplon Jozz Feslivol Clinic Schedule t5 Lionel Hompton School of Music Lionel Hampton - Biography 17 Universify of ldoho Guest futist Biographies .......... 23 Moscow, ldoho 83844-4014 Adjudicator Biog*pfri.r .................. 53 (208)885-ó513 l208l88 5-67 65 Fox: Lionel HamptonJazz Festival Staff ,.. -

Fffl Rulebook 2014

Page | 1 1 | Page Page | 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Section I Guidelines and Procedures 2 A. Teams 2 B. Players 3 C. Rosters 3 D. Equipment and Uniforms 4 E. Officials 7 F. Leagues 9 G. Tournaments 9 H. McNeill Poll Ranking System 13 Section II Rules and Regulations A. Fundamentals 14 B. Game Basics 17 C. Kick-offs 20 D. Offense 22 E. Punts 25 F. Defense 26 G. Miscellaneous Rules and Regulations 28 H. Rules Summary Sheet 31 Section III New Rule Changes Since 2012 32 Section IV Diagram for Fields (front of book) Section V Diagrams for Rushing (front of book) 2 | Page Page | 3 3 | Page Page | 1 FLORIDA FLAG FOOTBALL LEAGUE RULES Page | 2 SECTION I GUIDELINES AND PROCEDURES A. Teams 1. Certification: Any team that participates in any Florida Flag Football (FFFL) tournament must be FFFL certified in the current year. The team manager must present proof of certification or must pay the certification fee before participating in the tournament/league. Failure to obtain certification will prevent the team from participating in the tournament/league and will result in forfeiture of the entry fee. 2. Eligibility: To qualify for FFFL certification and to file for certification, the team manager must complete the proper certification form, which is available from the , tournament director, or Florida Flag Football website. This completed form is given to the league or tournament director for forwarding to FFFL, or may be sent directly to FFFL. There is a team certification fee that must be paid to FFFL. A Certification Year runs from January 1 - December 31. -

Meet the Tempe Playlist Musicians

MEET THE TEMPE PLAYLIST MUSICIANS Adele Etheridge Woodson Song: Morena (Morena feat. Rosita) Visit Website Morena was part of my EP, Sunday in the Park, that was commissioned by the city of Tempe! I wanted to create a fun, catchy track with Portuguese elements to bring fresh variety to the EP! I am a freelance composer and violinist born and raised in Tempe. I feel all of my artistic success is because of the local community and artists I am surrounded by. I currently compose music for film, arrange strings for other bands, and produce. Alex King Song: Dialogue (Inner) Visit Spotify After a spiraling last year and a half I was just trying to be honest with myself about what happened and where I was going. The results were less clear than where they started. Maybe? Not sure… I grew up here. I love this city. Although all the other places I've traveled too and have lived hold dear places in my heart, Tempe will always be my true love! I play drums in a loud band around Tempe infrequently. Alyssa G Song: Let Go Visit Instagram I was in a long and draining relationship for years and when I decided to move on and break it off, I found myself in tears in my friend’s dorm, guitar in hand, and humming to a few chords. I decided to write, record, and complete the song to share with others, in hope that they could see the light at the end of the tunnel when it comes to hard breakups. -

100 Contests of Trivia

100 Contests of Trivia In celebration of Williams Trivia's 100th contest, we have compiled 1 question from each contest (and even one from a contest that didn't happen) into a single super bonus. For some of the oldest contests, the questions have been lost, so we have improvised. For all the others, the question is one that was actually asked on the air. We've included the song that was played with the question, because that's one thing that has been the same about Williams Trivia from (almost) the very beginning. The song may or may not help you answer the question. Keep in mind that the answers to some questions may have changed since they were asked. Your answer should be what the answer should have been when the question was asked. Spring '66: Frank Ferry Question: Who was the winner of the first Trivia contest? Winter '66: Frank Ferry Question: We hardly know anything about this contest. But if you do, tell us about it and receive full credit for this question. Spring '67: Frank Ferry & WCFM Question: What is significant about the music from this contest? Winter '67: WCFM Question: What unbreakable record was set by Carter House in this contest? Spring '68: Frank Ferry & WCFM Question: What distinction does Morgan, the winner of this contest, hold? Winter '68: Morgan Question: Name any one of Groucho Marx's 3 consolation prize questions on \You Bet Your LIfe." Spring '69: Carter (featuring Frank Ferry) Question: This contest was the first to include a feature whereby competing teams could attempt to come up with trivia questions that would stump the hosting team. -

Page 1 of 163 Music

Music Psychedelic Navigator 1 Acid Mother Guru Guru 1.Stonerrock Socks (10:49) 2.Bayangobi (20:24) 3.For Bunka-San (2:18) 4.Psychedelic Navigator (19:49) 5.Bo Diddley (8:41) IAO Chant from the Cosmic Inferno 2 Acid Mothers Temple 1.IAO Chant From The Cosmic Inferno (51:24) Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo 3 Acid Mothers Temple 1.Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo (1:05:15) Absolutely Freak Out (Zap Your Mind!) 4 Acid Mothers Temple & The Melting Paraiso U.F.O. 1.Star Child vs Third Bad Stone (3:49) 2.Supernal Infinite Space - Waikiki Easy Meat (19:09) 3.Grapefruit March - Virgin UFO – Let's Have A Ball - Pagan Nova (20:19) 4.Stone Stoner (16:32) 1.The Incipient Light Of The Echoes (12:15) 2.Magic Aum Rock - Mercurical Megatronic Meninx (7:39) 3.Children Of The Drab - Surfin' Paris Texas - Virgin UFO Feedback (24:35) 4.The Kiss That Took A Trip - Magic Aum Rock Again - Love Is Overborne - Fly High (19:25) Electric Heavyland 5 Acid Mothers Temple & The Melting Paraiso U.F.O. 1.Atomic Rotary Grinding God (15:43) 2.Loved And Confused (17:02) 3.Phantom Of Galactic Magnum (18:58) In C 6 Acid Mothers Temple & The Melting Paraiso U.F.O. 1.In C (20:32) 2.In E (16:31) 3.In D (19:47) Page 1 of 163 Music Last Chance Disco 7 Acoustic Ladyland 1.Iggy (1:56) 9.Thing (2:39) 2.Om Konz (5:50) 10.Of You (4:39) 3.Deckchair (4:06) 11.Nico (4:42) 4.Remember (5:45) 5.Perfect Bitch (1:58) 6.Ludwig Van Ramone (4:38) 7.High Heel Blues (2:02) 8.Trial And Error (4:47) Last 8 Agitation Free 1.Soundpool (5:54) 2.Laila II (16:58) 3.Looping IV (22:43) Malesch 9 Agitation Free 1.You Play For -

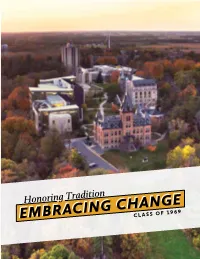

View the Viking Update

Honoring Tradition EMBRACING CHANGE CLASS OF ST. OLAF COLLEGE Class of 1969 – PRESENTS – The Viking Update in celebration of its 50th Reunion May 31 – June 2, 2019 Autobiographies and Remembrances of the Class stolaf.edu 1520 St. Olaf Avenue, Northfield, MN 55057 Advancement Division 800-776-6523 Student Editors Joshua Qualls ’19 Kassidy Korbitz ’22 Matthew Borque ’19 Student Designer Philip Shady ’20 Consulting Editor David Wee ’61, Professor Emeritus of English 50th Reunion Staff Members Ellen Draeger Cattadoris ’07 Cheri Floren Michael Kratage-Dixon Brad Hoff ’89 Printing Park Printing Inc., Minneapolis, MN Welcome to the Viking Update! Your th Reunion committee produced this commemorative yearbook in collaboration with students, faculty members, and staff at St. Olaf College. The Viking Update is the college’s gift to the Class of in honor of this milestone year. The yearbook is divided into three sections: Section I: Class Lists In the first section, you will find a complete list of everyone who submitted a bio and photo for the Viking Update. The list is alphabetized by last name while at St. Olaf. It also includes the classmate’s current name so you can find them in the Autobiographies and Photos section, which is alphabetized by current last name. Also included the class lists section: Our Other Classmates: A list of all living classmates who did not submit a bio and photo for the Viking Update. In Memoriam: A list of deceased classmates, whose bios and photos can be found in the third and final section of the Viking Update. Section II: Autobiographies and Photos Autobiographies and photos submitted by our classmates are alphabetized by current last name. -

The 3Rd Annual Mid-Atlantic Jazz Festival

February, 2012 Issue 340 jazz &blues report now in our 38th year The 3rd Annual February 2012 • Issue 340 Nicholas Payton Mid-Atlantic Jazz Festival The 3rd Annual Mid-Atlantic Jazz Festival By Ron Weinstock Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Layout & Design Bill Wahl Operations Jim Martin Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Dewey Forward, Nancy Ann Lee, Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Dave Sunde, Joerg Unger, Duane Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Check out our constantly updated website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record Photo by Martin Philbey labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 years of reviews are up and we’ll be going all the way back to 1974. Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com Web www.jazz-blues.com Copyright © 2012 Jazz & Blues Report No portion of this publication may be re- produced without written permission from the publisher. All rights Reserved. Founded in Buffalo New York in March of 1974; began in Cleveland edition in April of 1978. Now this global e-zine edition is posted online monthlyat www.jazz-blues. com Paul Carr As I write, it is about 5 weekends from the 3rd Annual Mid-Atlantic Jazz Festival. The Mid-Atlantic Jazz Festival revives the legacy of the East Coast Jazz Festival that ran for 15 years starting in 1992. The ECJF originated in honor of Elmore “Fish” Middleton, a Washington, DC jazz radio programmer, whose commitment to promoting jazz music and supporting emerging jazz www.jazz-blues.com artists became the guiding principle behind the festival. The driving force of the ECJF was the late Ronnie Wells, a Washington DC jazz icon.