PROTECTING ECONOMIC REFORM by SEEKING MEMBERSHIP in LIBERAL INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS DISSERTATION Presented in Fulfillment Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unsettled Debate: Monarchy and Republic in Spain and Greece in the Interwar Years*

■ Assaig] ENTREMONS. UPF JOURNAL OF WORLD HISTORY Barcelona ﺍ Universitat Pompeu Fabra Número 6 (juny 2014) www.entremons.org The Unsettled Debate: Monarchy and Republic in Spain and Greece in the Interwar Years* Enric UCELAY-DA CAL (Universitat Pompeu Fabra) abstract The following essay examines the political development in Spain and Greece between the World War I and World War II, comparing these two Mediterranean countries and placing them in a broader European and global context. The conflict between the supporters of monarchy and republic as forms of government was extremely important in the political debate in both countries, and shaped their history in a quite remarkable way. The discussion of these intricate dynamics will help to appreciate the problems that Spain and Greece faced at that time, and can also contribute to a deeper understanding of some key features of the historical change in these two countries. resumen El siguiente ensayo examina el desarrollo político en España y Grecia en el período entre la Primera y la Segunda Guerra Mundial, comparando estos dos países mediterráneos y situándolos en un contexto europeo y global más amplio. El conflicto entre los partidarios de la monarquía y la república como formas de gobierno fue muy importante en el debate político de ambos países, influyendo en su historia de una manera muy notable. La discusión de estas dinámicas complicadas ayudará a apreciar mejor los problemas a los que España y Grecia se enfrentaban en ese momento, contribuyendo asimismo a una comprensión más profunda de algunas de las características clave del cambio histórico en estos dos países. -

Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2013 Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit Caitlin Rickert Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Health Communication Commons Recommended Citation Rickert, Caitlin, "Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit" (2013). Master's Theses. 136. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/136 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT by Caitlin Rickert A Thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Communication Western Michigan University April 2013 Thesis Committee: Heather Addison, Ph. D., Chair Sandra Borden, Ph. D. Joseph Kayany, Ph. D. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT Caitlin Rickert, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2013 This study explores how The Biggest Loser, a popular television reality program that features a weight-loss competition, reflects and magnifies established stereotypes about obese individuals. The show, which encourages contestants to lose weight at a rapid pace, constructs a broken/fixed dichotomy that oversimplifies the complex issues of obesity and health. My research is a semiotic analysis of the eleventh season of the program (2011), focusing on three pairs of contestants (or “couples” teams) that each represent a different level of commitment to the program’s values. -

Discussion Paper

Zentrum für Europäische Integrationsforschung Center for European Integration Studies Rheinische Friedrich Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Discussion Paper Eva Slivková Slovakia’s Response on the Regular report form the European Commission on Progress towards Accession C 57 1999 Eva Slivková, Born 1971, works for the Slovak Ministry of Foreign Affairs, division of chief negotiations. After receiving a degree in Translation (German and English), she worked as a journalist for the Slovak newspa- per Slovensky Dennik in 1990/91. As a member of the Slovak Christian Democratic Movement (KDH), she worked in the field of Public Relations within the KDH from 1992 to 1994. In 1993 she started working as a Public Relations Assistant of the Iowa-State- University-Foundation until 1996. 1996 she completed an in- ternship at the German parliament in the office of Rudolf Seiters (MP CDU). In 1997/98 Ms. Slivková was a Project Manager at the Centre for European politics and worked as a freelance Translator. Eva Slivkova Slovakia’s Response on the Regular Report from the European Commission on Progress towards Accession Introduction Looking at today’s Slovakia one can get the feeling of being in the Phoe- nix fairy-tale. It seems as if Slovakia needed to go through a purifying fire in order to shine in the full beauty of the Phoenix. The result of the last four years is a country, where the lie was a working method, human dignity was trampled, and citizens played only a minor role in issues that influenced their lives. Constantly-repeated statements about freedom, hu- man rights, democracy and a flourishing economy became untrustworthy and empty phrases. -

International Organizations

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS EUROPEAN SPACE AGENCY (E.S.A.) Headquarters: 8–10 Rue Mario Nikis, 75738 Paris, CEDEX 15, France phone 011–33–1–5369–7654, fax 011–33–1–5369–7651 Chairman of the Council.—Alain Bensoussan (France). Director General.—Antonio Rodota (Italy). Member Countries: Austria Germany Portugal Belgium Ireland Spain Denmark Italy Sweden Finland Netherlands Switzerland France Norway United Kingdom Cooperative Agreement.—Canada. European Space Operations Center (E.S.O.C.), Robert Bosch-Strasse 5, 61, Darmstadt, Germany, phone 011–49–6151–900, telex: 419453, fax 011–49–6151–90495. European Space Research and Technology Center (E.S.T.E.C.), Keplerlaan 1, 2201, AZ Noordwijk, Zh, Netherlands, phone 011–31–71–565–6565; Telex: 844–39098, fax 011–31–71–565–6040. Information Retrieval Service (E.S.R.I.N.), Via Galileo Galilei, Casella Postale 64, 00044 Frascati, Italy. Phone, 011–39–6–94–18–01; Telex: 610637, fax 011–39–94–180361. Washington Office (E.S.A.), Suite 7800, 955 L’Enfant Plaza SW. 20024. Head of Office.—I.W. Pryke, 488–4158, fax: (202) 488–4930, [email protected]. INTER-AMERICAN DEFENSE BOARD 2600 16th Street 20441, phone 939–6041, fax 939–6620 Chairman.—MG Carl H. Freeman, U.S. Army. Vice Chairman.—Brigadier General Jose´ Mayo, Air Force, Paraguay. Secretary.—Col. Robert P. Warrick, U.S. Air Force. Vice Secretary.—CDR Carlos Luis Rivera Cordova, Navy. Deputy Secretary for Administration.—LTC Frederick J. Holland, U.S. Army. Conference.—Maj. Robert L. Larson, U.S. Army. Finance.—Maj. Stephen D. Zacharczyk, U.S. Army. Information Management.—Maj. -

Rock for Beginners – Miguel Amorós

Rock for Beginners – Miguel Amorós Shake, Rattle and Roll “Rock”, properly speaking, refers to a particular musical style created by Anglo-Saxon youth culture that spread like wildfire to every country where the modern conditions of production and consumption had reached a certain qualitative threshold, that is, where capitalism had given rise to a mass society of socially uprooted individuals. The phenomenon first took shape after World War Two in the United States, the most highly developed capitalist country, and then spread to England; from there it returned like a boomerang to the country of its origin, irradiating its influence everywhere, changing people’s lives in different ways. To get a better understanding of rock, we will first have to review the concepts of subculture, music and youth. The word “subculture” refers to the behaviors, values, jargons and symbols of a separate milieu—ethnic, geographic, sexual or religious—within the dominant culture, which was, and still is, of course, the culture of the ruling class. Beginning in the sixties, once the separation was imposed from above between elite culture, reserved for the leaders, and mass culture, created to regiment the led, to coarsen their tastes and brutalize their senses—between high culture and masscult,1 as Dwight McDonald called them—the term would be used to refer to alternative consumerist lifestyles, which were reflected in various ways in the music that was at first called “modern” music, and then pop music. The mechanism of identification that produced youth subculture was ephemeral, since it was constantly being offset by the temporary character of youth. -

Legitimacy by Proxy: Searching for a Usable Past Through the International Brigades in Spain's Post-Franco Democracy, 1975-201

This is a repository copy of Legitimacy by Proxy: searching for a usable past through the International Brigades in Spain’s post-Franco democracy, 1975-2015. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/93332/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Marco, J and Anderson, PP (2016) Legitimacy by Proxy: searching for a usable past through the International Brigades in Spain’s post-Franco democracy, 1975-2015. Journal of Modern European History, 14 (3). pp. 391-410. ISSN 1611-8944 10.17104/1611-8944-2016-3-391 (c) 2016, Verlag C.H. Beck. This is an author produced version of a paper published in the Journal of Modern European History. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Legitimacy by Proxy: searching for a usable past through the International Brigades in Spain’s post-Franco democracy, 1975-2015 INTRODUCTION The 23 October 2011 marked the 75th anniversary of the official creation of the International Brigades. -

Information Campaign for the 2014 Elections to the European Parliament in Slovakia

INFORMATION CAMPAIGN FOR THE 2014 ELECTIONS TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT IN SLOVAKIA 16 September 2013 - 25 May 2014 Presidential Debate (p5;25) Mr. Schulz visit (p2;22) Election Night (p3;27) European Parliament Information Office in Slovakia started the official information campaign for the 2014 Elections to the European Parliament in Slovakia in September 2013. Since then, almost 60 events, discussion forums, outdoor activities and dialogues took place in more than 20 towns and cities across the Slovak Republic. In addition, 6 nationwide competitions focusing on the European Elections were initiated. The most significant and interesting moments of our information campaign were definitely the visit of the EP President Martin Schulz in the Celebration of the 10th Anniversary of the EU membership in Bratislava on 30 April 2014, Election Night dedicated to the official announcement of the results of the 2014 Elections to the European Parliament in Slovakia on 25 May 2014 in the EPIO´s office in Bratislava, four outdoor events dedicated to the Celebration of the 10th Anniversary of the Slovak membership in the EU accompanied by the information campaign to the EE2014 taking place from April to May in four largest Slovak towns (Bratislava, Košice, Banská Bystrica and Žilina) and the watching of live stream of the Presidential Debate accompanied by analytical discussions on 15 May 2014. These activities caught the attention of hundreds of Slovaks who directly participated in them and other thousands of citizens who expressed their interest for our activities through social media. CONTENT I. Most significant moments of the EE2014 Information Campaign in Slovakia............................. -

Forty Years of Democratic Spain: Political, Economic, Foreign Policy

Working Paper Documento de Trabajo Forty years of democratic Spain Political, economic, foreign policy and social change, 1978-2018 William Chislett Working Paper 01/2018 | October 2018 Sponsored by Bussiness Advisory Council With the collaboration of Forty years of democratic Spain Political, economic, foreign policy and social change, 1978-2018 William Chislett - Real Instituto Elcano - October 2018 Real Instituto Elcano - Madrid - España www.realinstitutoelcano.org © 2018 Real Instituto Elcano C/ Príncipe de Vergara, 51 28006 Madrid www.realinstitutoelcano.org ISSN: 1699-3504 Depósito Legal: M-26708-2005 Working Paper Forty years of democratic Spain Political, economic, foreign policy and social change, 1978-2018 William Chislett Summary 1. Background 2. Political scene: a new mould 3. Autonomous communities: unfinished business 4. The discord in Catalonia: no end in sight 5. Economy: transformed but vulnerable 6. Labour market: haves and have-nots 7. Exports: surprising success 8. Direct investment abroad: the forging of multinationals 9. Banks: from a cosy club to tough competition 10. Foreign policy: from isolation to full integration 11. Migration: from a net exporter to a net importer of people 12. Social change: a new world 13. Conclusion: the next 40 years Appendix Bibliography Working Paper Forty years of democratic Spain Spain: Autonomous Communities Real Instituto Elcano - 2018 page | 5 Working Paper Forty years of democratic Spain Summary1 Whichever way one looks at it, Spain has been profoundly transformed since the 1978 -

Download/Print the Study in PDF Format

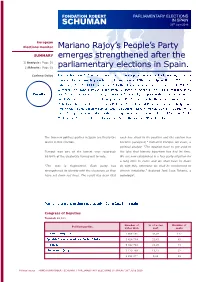

PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS IN SPAIN 26th June 2016 European Elections monitor Mariano Rajoy’s People’s Party SUMMARY emerges strengthened after the 1) Analysis : Page 01 2) Résults : Page 03 parliamentary elections in Spain. Corinne Deloy The People’s Party (PP) led by the President of the outgoing government Mariano Rajoy came out ahead in the parliamentary elections that took place on 26th June in Spain. It won 33% of the vote and 137 seats (+14 in comparison with the previous election on 20th December last) in the Congreso, the lower chamber of parliament. It came out ahead of the Socialist Workers’ Party Results (PSOE) led by Pedro Sanchez who, contrary to forecasts by the pre-election polls, remained the country’s second most important party winning 22.66% of the vote, the second lowest score in its history, and 85 seats (- 5). Unidos Podemos, the alliance of Podemos, led by Pablo Iglesias, and the United Left (Izquierda Unida, IU), led by Alberto Garzon, won 21.26% of the vote and 71 seats. Both parties won 24.40% of the vote together on 20th December last and 71 seats. Finally Ciudadanos (C’s) led by Alberto Rivera won 13% of the vote and 32 seats (- 8). The two new political parties in Spain are finally the each has stuck to its position and the system has losers in this election. become paralysed,” indicated Enrique Gil Cavo, a political analyst. “The Spanish have to get used to Turnout was one of the lowest ever recorded: the idea that historic bipartism has had its time. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Charlas En La Prisión - Pág

Colección dirigida por: Alfonso C. Comín Juan N. García Nieto, Manuel Ludevid Eduardo Martín Carlos Navales Carlos Obeso. Jesús Salvador Equipo Estudios Laborales (Madrid) © by Marcelino Camacho, 1976 © de esta edición (incluida la «Carta abierta» y el diseño de la cubierta): Editorial Laia, S. A., Constitución, 18-20, Barcelona-14 Primera edición: Ediciones Ebro, París, Segunda edición (primera en España): Editorial Laia, Barcelona, mayo, 1976 Cubierta de Enric Satué Depósito legal: B. 22 788 - 1976 ISBN: 84-7222-954-8 Impreso y encuadernado en Romanyá/Valls Verdaguer, 1 - Capellades/Barcelona Printed in Spain Colección Primero de Mayo Editorial Laia Barcelona 1976 Marcelino Camacho - Charlas en la prisión - pág. 2 CARTA ABIERTA A MARCELINO CAMACHO Me pides que te haga un prólogo, y claro, esto me honra. ¿Cómo ne- garme? Y, sin embargo, ¿qué decir? ¿Quién no sabe quién eres y todo lo que eres, cuánto representas para este pueblo nuestro de cada día? Te has identificado con tu clase, de tal modo, que tú y tu clase sois una misma cosa, Marcelino. No has salido nunca por TV —¿os imagináis, Marceli- no, clase obrera, saliendo, hablando por TV, diciendo la verdad obrera por TV, clamando amnistía por TV?— y sin embargo todos os conocen, todos conocen vuestro rostro, el deje y el más leve gesto al salir de Cara- banchel y abrazar a Josefina. Marcelino Camacho, el hombre de comisiones obreras, producto de un colectivo en lucha. Tú y tu clase tenéis la densidad del Canto General de Pablo Neruda, el barro de Miguel Hernández, la vibración histórica de Dolores Ibarruri, la calidad democrática de Julián Besteiro, recuperáis la voz de anónimo urbano y el canto de siega del campo andaluz.. -

Placer Helado Bajo Cero

NÚMERO 65 AGOSTO/SEPTIEMBRE 2018 BIMESTRAL ARAGONÉS DE GASTRONOMÍA Y ALIMENTACIÓN bajo cero EN HUESCA TATAU NUEVA SECCIÓN placer ENOTURISMO FESTIVAL helado VINO SOMONTANO SUMARIO FESTIVAL VINO SOMONTANO AGOSTO/ BIRRAGOZA SEPTIEMBRE IV LIGA DE LA TORTILLA 2018 AGENDA pág. 92-96 65 Los helados LA GASTRONOMÍA BAJO CERO PRESUME DE BUENA REPRESENTACIÓN ARTESANA EN ARAGÓN UNA EDITA INDUSTRIA Adico PARA GOZAR DIRECTOR DEL FRÍO José Miguel Martínez Urtasun REPOR > PÁG. 41-49 DIRECTOR DE ARTE Gabi Orte / chilindron.es PROYECTO GRÁFICO M Soluciones Gráficas COLABORAN EN ESTE PROYECTO Joaquín Muñoz, Ana Mallén, Tomás Caró, María Montes, Mariano Navascués, David Olmo, Jorge Hernández, Lalo Tovar, Natalia Huerta, Manuel Bona, Ana Caudevilla, Joan Rosell, Fernando Mora, Guillermo Orduña, PASTILLO DE MANZANA TATAU, ¿TAPAS O PLATOS? Francisco Abad, Carlos Pérez, YOU CAN > PÁG. 57-59 EL BUSCÓN> PÁG 82-83 Fernando Montes, Francisco Orós, Pepe Bonillo, Elena Bernad. ASESORES Miguel Ángel Revuelto, David Baldrich FOTOGRAFÍA Gabi Orte / archivo FOTO PORTADA Gabi Orte | chilindron.es AGRADECIMIENTOS Restaurantes Uncastello HECHO EN LOS PIRINEOS y Palomeque; Helados Elarte, TU HUESCA> PÁG. 60-61 Ziart y Lyc. REDACCIÓN Y PUBLICIDAD ADICO Albareda 7, 1º, 2ª 50004 Zaragoza 976 232 552 / 682 830 711 [email protected] IMPRIME CARMELO BOSQUE Calidad Gráfica, SL LA ENTREVISTA> PÁG. 32-33 DISTRIBUYE Valdebro Publicaciones, SA ADEMÁS RECETAS Seis fórmulas de diferentes helados. GASTRONÓMADAS Las mejores propuestas con ternasco. WINELOVER Jorge Orte. ENOTURISMO Nueva DepÓSIto legal Z-4429-2009 sección para viajar con vino. BARRA LIBRE El Chartreuse. GASTRO NÚMERO 65 3 AGO/SEP 2018 EDITORIAL JOSÉ MIGUEL MARTÍNEZ URTASUN Director y editor de GASTRO ARAGÓN AGOSTO, UN DESCANSO PARA REFLEXIONAR ¿DESAPARECERÁN YA ESAS COOPERATIVAS DEDICADAS A SUMINISTRAR MANO DE OBRA A LOS MATADEROS? ¿RECUPERARÁ EL GOBIERNO LAS HOSPEDERÍAS INSUMISAS? ¿QUÉ TIENE ORDESA QUE A TANTOS SEDUCE? ¿cuántos bares sin cocina cerrarán EN BREVE EN ZARAGOZA? REFLEXIÓN.