The Role of Media in the Development of Professional Baseball in New York from 1919-1929

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York

The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and The Politics of New York NEIL J. SULLIVAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX This page intentionally left blank THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX yankee stadium and the politics of new york N EIL J. SULLIVAN 1 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paolo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2001 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN 0-19-512360-3 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Carol Murray and In loving memory of Tom Murray This page intentionally left blank Contents acknowledgments ix introduction xi 1 opening day 1 2 tammany baseball 11 3 the crowd 35 4 the ruppert era 57 5 selling the stadium 77 6 the race factor 97 7 cbs and the stadium deal 117 8 the city and its stadium 145 9 the stadium game in new york 163 10 stadium welfare, politics, 179 and the public interest notes 199 index 213 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This idea for this book was the product of countless conversations about baseball and politics with many friends over many years. -

After One of the Worst Starts Ever to a Baseball Career, John J. Mcgraw Became a Sports Legend As a Champion Player and Manager in the Early 20Th Century

After one of the worst starts ever to a baseball career, John J. McGraw became a sports legend as a champion player and manager in the early 20th century. John Joseph McGraw was born in Truxton, Cortland County, on April 7, 1873. His relationship with his father grew strained after John’s mother and four siblings died during an epidemic in the winter of 1884-5. John left home while still in school, where he starred on the baseball team. Obsessed with the game, he spent the money he earned from odd jobs on baseball equipment and rulebooks. In 1890, John decided to make a career of baseball. He started out earning $5 a game for the Truxton Grays. When the Grays’ manager took over the Olean franchise of the New York-Penn League, John became his third baseman. He committed eight Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [reproduction errors in his rst game with Olean. After six games, he number LC-DIG-ggbain-34093] was cut from the team. McGraw kept trying. He played shortstop for Wellsville in the Western New York League and showed skill as a hitter and baserunner. After the 1890 season, McGraw joined the American All-Stars, a team that toured the southern states and Cuba during the winter. In 1891, a team of All-Stars and Florida players challenged the Cleveland Spiders of the American Association, one of the era’s two major leagues, to a spring-training exhibition game. Cleveland won, but McGraw got three hits in ve at-bats. Coverage of the game in The Sporting News inspired several teams to offer McGraw contracts. -

NLDS Notes GM 4.Indd

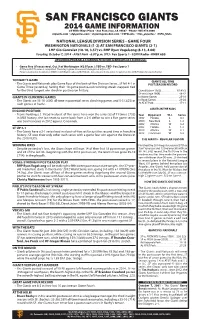

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2014 GAME INFORMATION 24 Willie Mays Plaza •San Francisco, CA 94107 •Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com •sfgigantes.com •sfgiantspressbox.com •@SFGiants •@los_gigantes• @SFG_Stats NATIONAL LEAGUE DIVISION SERIES - GAME FOUR WASHINGTON NATIONALS (1-2) AT SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (2-1) LHP Gio Gonzalez (10-10, 3.57) vs. RHP Ryan Vogelsong (8-13, 4.00) Tuesday, October 7, 2014 • AT&T Park • 6:07 p.m. (PT) • Fox Sports 1 • ESPN Radio • KNBR 680 UPCOMING PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS & BROADCAST SCHEDULE: • Game Five (if necessary), Oct. 9 at Washington (#2:07p.m.): TBD vs. TBD- Fox Sports 1 # If the LAD/STL series is completed, Thursday's game time would change to 5:37p.m. PT Please note all games broadcast on KNBR 680 AM (English radio) and ESPN Radio. All postseason home games broadcast on 860 AM ESPN Deportes (Spanish radio). TONIGHT'S GAME GIANTS ALL-TIME • The Giants and Nationals play Game Four of this best-of- ve Division Series...SF fell 4-1 in POSTSEASON RECORD Game Three yesterday, having their 10-game postseason winning streak snapped, tied for the third-longest win streak in postseason history. Overall (since 1900) . 87-83-2 SF-era (since 1958) . .48-42 GIANTS IN CLINCHING GAMES In Home Games . .25-18 • The Giants are 15-10 (.600) all-time in potential series clinching games and 5-3 (.625) in In Road Games. .23-24 such games at home. At AT&T Park . .17-11 GIANTS IN THE NLDS IN GOOD POSITION • Teams holding a 2-1 lead in a best-of- ve series have won the series 52 of 71 times (.732) Year Opponent W-L Series in MLB history...the last team to come back from a 2-0 de cit to win a ve game series 1997 Florida L 0-3 was San Francisco in 2012 against Cincinnati. -

Guide to the Babe Ruth Scrapbooks, 1921-1935

Guide to the Lou Gehrig Scrapbooks, 1920-1942 National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhalloffame.org This guide to the scrapbooks was prepared by Howard Hamme, Intern 2007 and reviewed by Claudette Burke in December 2007. Collection Number: BA SCR 54 BL-268.56 & BL-269.56 Title: Lou Gehrig Scrapbooks Inclusive Dates: 1920-1942 Extent: 2.2 linear feet (5 scrapbooks) Repository: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract: This collection contains the scrapbooks of Henry Louis Gehrig, with materials collected by his wife Eleanor Gehrig. The scrapbooks cover the years 1920-1942, with a variety of materials documenting Gehrig’s activities on and off-field, beginning with his youth and ending with coverage of his death. Original donated scrapbooks were in two volumes. Conserved in October 2005 by NEDCC. Acquisition Information: This collection was a gift of Mrs. Eleanor Gehrig in 1956. Preferred Citation: Lou Gehrig Scrapbooks, BA SCR 54, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, National Baseball Hall of Fame. Access Restrictions: By appointment only. Available Monday - Friday from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. A Finding aid and microfilm copy available. Copyright: Property rights reside with the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. For further information on reproduction and publication, please contact the library. Separations: None Processing Information: This collection was processed by Howard Hamme and reviewed by Claudette Burke in December 2007. History Lou Gehrig had 13 consecutive seasons with both 100 runs scored and 100 RBI, averaging 139 runs and 148 RBI. -

Bridgeportsandmohawks Ofmeriden Clash Here Sunday

Pae Four THE BRIDGEPORT TIMES Saturday, Oct: 15, 1921 rts And Mohawks OfMeriden Clash Here Bridgepo- Sunday OUTDOOR SPORTS HERE'S A SHOCK! By Tad Football 1 LOCAL BALL CLUB ow ONLY BROKE EVEN Sport By GEORGE E. FIRSTBROOK. Monarch Although the past admissions to Nwfleld Park totaled between 80.000 ANDERSON PLEASED and 90,000 in the 1921 baseball sea- son, an increase over last season, I RGES WEIGHT LIMIT there were no mountain high profits OVER VICTORY OF according to Clark Lane, Jr., presi- FOR FOOTBALL ELEVENS dent of the Bridgeport Baseball club. 3"he guessing slats of fans who have D, H. S. RUNNERS New Haven, Oct. 13 John Heis-ma- n, been estimating the profits of the lo-c- the University of Pennsylvania club all the from $10,000 to coach and formerly of Georgia way came In The 520.000 have been badly shattered, CHICK CREATON. Tech, out today Yale according to Mr. Lane's dope. By Daily Xews favoring decision of "We managed to break about even Minus the services of six members ffkvthsll plrvon in three lnsses . and' are well satisfied," said Mr. Lane of its regular squad, through ineligi- Iieavywe-ights- middleweights and ( yesterday. bility, the Bridgeport High School Hill lightweights. The weights at which ' Albany Jumps Expensive. and Dale team easily won over the he would make the classification 'Mr. Lane explained that while the Bristol High Run yesterday afternoon are 165. 155 and 145 pounds. He ' were ex- by a score of 23-3- 2. stated that he felt that many of the htae crowds good the heavy n-n- panse involved in theMbng jumps, Matty Skane. -

Christy Mathewson Was a Great Pitcher, a Great Competitor and a Great Soul

“Christy Mathewson was a great pitcher, a great competitor and a great soul. Both in spirit and in inspiration he was greater than his game. For he was something more than a great pitcher. He was The West Ranch High School Baseball and Theatre Programs one of those rare characters who appealed to millions through a in association with The Mathewson Foundation magnetic personality attached to clean honesty and undying loyalty present to a cause.” — Grantland Rice, sportswriter and friend “We need real heroes, heroes of the heart that we can emulate. Eddie Frierson We need the heroes in ourselves. I believe that is what this show you’ve come to see is all about. In Christy Mathewson’s words, in “Give your friends names they can live up to. Throw your BEST pitches in the ‘pinch.’ Be humble, and gentle, and kind.” Matty is a much-needed force today, and I believe we are lucky to have had him. I hope you will want to come back. I do. And I continue to reap the spirit of Christy Mathewson.” “MATTY” — Kerrigan Mahan, Director of “MATTY” “A lively visit with a fascinating man ... A perfect pitch! Pure virtuosity!” — Clive Barnes, NEW YORK POST “A magnificent trip back in time!” — Keith Olbermann, FOX SPORTS “You’ll be amazed at Matty, his contemporaries, and the dramatic baseball events of their time.” — Bob Costas, NBC SPORTS “One of the year’s ten best plays!” — NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO “Catches the spirit of the times -- which includes, of course, the present -- with great spirit and theatricality!” -– Ira Berkow, NEW YORK TIMES “Remarkable! This show is as memorable as an exciting World Series game and it wakes up the echoes about why we love An Evening With Christy Mathewson baseball. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Digital Collections

MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVIEW THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI, COLUMBIA THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI The State Historical Society of Missouri, heretofore organized under the laws of the State, shall be the trustee of this State-Laws of Missouri, 1899, R.S. of Mo., 1969, chapter 183, as revised 1978. OFFICERS, 1998-2001 LAWRENCE O. CHRISTENSEN, Rolla, President JAMES C. OLSON, Kansas City, First Vice President SHERIDAN A. LOGAN, St. Joseph, Second Vice President VIRGINIA G. YOUNG, Columbia, Third Vice President NOBLE E. CUNNINGHAM, JR., Columbia, Fourth Vice President R. KENNETH ELLIOTT, Liberty, Fifth Vice President ROBERT G. J. HOESTER, Kirkwood, Sixth Vice President ALBERT M. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer JAMES W. GOODRICH, Columbia, Executive Director, Secretary, and Librarian PERMANENT TRUSTEES FORMER PRESIDENTS OF THE SOCIETY H. RILEY BOCK, New Madrid ROBERT C. SMITH, Columbia LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville Avis G. TUCKER, Warrensburg TRUSTEES, 1997-2000 JOHN K. HULSTON, Springfield ARVARH E. STRICKLAND, Columbia JAMES B. NUTTER, Kansas City BLANCHE M. TOUHILL, St. Louis BOB PRIDDY, Jefferson City HENRY J. WATERS III, Columbia DALE REESMAN, Boonville TRUSTEES, 1998-2001 WALTER ALLEN, Brookfield VIRGINIA LAAS, Joplin CHARLES R. BROWN, St. Louis EMORY MELTON, Cassville VERA F. BURK, Kirksville DOYLE PATTERSON, Kansas City DICK FRANKLIN, Independence JAMES R. REINHARD, Hannibal TRUSTEES, 1999-2002 BRUCE H. BECKETT, Columbia W. GRANT MCMURRAY, Independence CHARLES B. BROWN, Kennett THOMAS L. MILLER, SR., Washington DONNA J. HUSTON, Marshall PHEBE ANN WILLIAMS, Kirkwood JAMES R. MAYO, Bloomfield EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Eight trustees elected by the board of trustees, together with the president of the Society, consti tute the executive committee. -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

GILIRE's ORDER Cut One In

10 TIIF MORNING OREGONIAN. MONDAY. MARCII ,2, 1914. the $509 and the receipts, according to their fthev touched him fnr k!t hltw and five name straightened out and made standing the end of the tourney. runs. usual announcement. it House, a pitcher from the NOT FOR ' "Rehg battiug for Adams." CLEAN BASEBALL HARD SWIM FATAL E IS HOLDOUT; ...recruited BERGER ' 11-- Central Association, twirled the fifth, "That is another boot you have OREGOMAS BEAT ZEBRAS, 3 sixth and seventh innings and Kills made Ump. I am going to get a hit Johnson, from the Racine, Wis., club, for myself," said Rehg. He made Gene Rich, .Playing "Star Game for the last two. Johnson is a giant, with good his threat with a single. CAViLL FIXED a world of speed. He fanned six of SERAPHS, IS REPORT Last year he pulled one at the ex- GILIRE'S ORDER TO ARTHUR J JUMP PRICE Winners; injured. the seven batters who faced him. pense of George McBrlde, that at first was an- made the brilliant shortstop sore, and The fourth straight victory PLEASANTON, Cal., March 1. (Spe- then on second thought made him nexed by --the Oregonia Club basketball cial.) Manager' Devlin, of th6 Oaks, laugh. Rehg was coaching at third, team against the Zebras yesterday. The was kept busy today, taking part in when an unusually difficult grounder winners scored 11 points-t- the Zebras' the first practice game of the training Angel was hit to MBride's right. Off with Ex-Wor- 3. was played on the Jew- Shortpatcher Is Federal President Says That ld; in The match First Baseman Asks $30,000 ' assembling Former. -

American Hercules: the Creation of Babe Ruth As an American Icon

1 American Hercules: The Creation of Babe Ruth as an American Icon David Leister TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas May 10, 2018 H.W. Brands, P.h.D Department of History Supervising Professor Michael Cramer, P.h.D. Department of Advertising and Public Relations Second Reader 2 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………...Page 3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….Page 5 The Dark Ages…………………………………………………………………………..…..Page 7 Ruth Before New York…………………………………………………………………….Page 12 New York 1920………………………………………………………………………….…Page 18 Ruth Arrives………………………………………………………………………………..Page 23 The Making of a Legend…………………………………………………………………...Page 27 Myth Making…………………………………………………………………………….…Page 39 Ruth’s Legacy………………………………………………………………………...……Page 46 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………….Page 57 Exhibits…………………………………………………………………………………….Page 58 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………….Page 65 About the Author……………………………………………………………………..……Page 68 3 “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend” -The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance “I swing big, with everything I’ve got. I hit big or I miss big. I like to live as big as I can” -Babe Ruth 4 Abstract Like no other athlete before or since, Babe Ruth’s popularity has endured long after his playing days ended. His name has entered the popular lexicon, where “Ruthian” is a synonym for a superhuman feat, and other greats are referred to as the “Babe Ruth” of their field. Ruth’s name has even been attached to modern players, such as Shohei Ohtani, the Angels rookie known as the “Japanese Babe Ruth”. Ruth’s on field records and off-field antics have entered the realm of legend, and as a result, Ruth is often looked at as a sort of folk-hero. This thesis explains why Ruth is seen this way, and what forces led to the creation of the mythic figure surrounding the man.