Maral Book Final .Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Britain, British Petroleum, Shell and the Remaking of the International Oil Industry, 1957-1979

Empires of Energy: Britain, British Petroleum, Shell and the Remaking of the International Oil Industry, 1957-1979 Author: Jonathan Robert Kuiken Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104079 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2013 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of History EMPIRES OF ENERGY: BRITAIN, BRITISH PETROLEUM, SHELL AND THE REMAKING OF THE INTERNATIONAL OIL INDUSTRY, 1957-1979 [A dissertation by] JONATHAN R. KUIKEN submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2013 © copyright by JONATHAN ROBERT KUIKEN 2013 Empires of Energy: Britain, British Petroleum, Shell and the remaking of the international oil industry, 1957-1979 Jonathan R. Kuiken Dissertation Advisor - James E. Cronin Dissertation Abstract This dissertation examines British oil policy from the aftermath of the Suez Crisis in 1956-1957 until the Iranian Revolution and the electoral victory of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party in 1979. It was a period marked by major transitions within Britain’s oil policy as well as broader changes within the international oil market. It argues that the story of Britain, and Britain’s two domestically-based oil companies, BP and Shell, offers a valuable case study in the development of competing ideas about the reorganization of the international oil industry in the wake of the rise of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting countries and the companies’ losing control over the production of oil. -

The Real 007 Used Fake News to Get the U.S. Into World War II About:Reader?Url=

The Real 007 Used Fake News to Get the U.S. into World War II about:reader?url=http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2017/01/29/the-r... thedailybeast.com Marc Wortman01.28.17 10:00 PM ET Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast CLOAK & DAGGER The British ran a massive and illegal propaganda operation on American soil during World War II—and the White House helped. In the spring of 1940, British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill was certain of one thing for his nation caught up in a fight to the death with Nazi Germany: Without American support his 1 of 11 3/20/2017 4:45 PM The Real 007 Used Fake News to Get the U.S. into World War II about:reader?url=http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2017/01/29/the-r... nation might not survive. But the vast majority of Americans—better than 80 percent by some polls—opposed joining the fight to stop Hitler. Many were even against sending any munitions, ships or weapons to the United Kingdom at all. To save his country, Churchill had not only to battle the Nazis in Europe, he had to win the war for public opinion among Americans. He knew just the man for the job. In May 1940, as defeated British forces were being pushed off the European continent at Dunkirk, Churchill dispatched a soft-spoken, forty-three-year-old Canadian multimillionaire entrepreneur to the United States. William Stephenson traveled under false diplomatic passport. MI6—the British secret intelligence service—directed Stephenson to establish himself as a liaison to American intelligence. -

Metal Men Metal Men Marc Rich and the $10 Billion Scam A

Metal Men Metal Men Marc Rich and the $10 Billion Scam A. Craig Copetas No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, scanning or any information storage retrieval system, without explicit permission in writing from the Author. © Copyright 1985 by A. Craig Copetas First e-reads publication 1999 www.e-reads.com ISBN 0-7592-3859-6 for B.D. Don Erickson & Margaret Sagan Acknowledgments [ e - reads] Acknowledgments o those individual traders around the world who allowed me to con- duct deals under their supervision so that I could better grasp the trader’s life, I thank you for trusting me to handle your business Tactivities with discretion. Many of those traders who helped me most have no desire to be thanked. They were usually the most helpful. So thank you anyway. You know who you are. Among those both inside and outside the international commodity trad- ing profession who did help, my sincere gratitude goes to Robert Karl Manoff, Lee Mason, James Horwitz, Grainne James, Constance Sayre, Gerry Joe Goldstein, Christine Goldstein, David Noonan, Susan Faiola, Gary Redmore, Ellen Hume, Terry O’Neil, Calliope, Alan Flacks, Hank Fisher, Ernie Torriero, Gordon “Mr. Rhodium” Davidson, Steve Bronis, Jan Bronis, Steve Shipman, Henry Rothschild, David Tendler, John Leese, Dan Baum, Bert Rubin, Ernie Byle, Steven English and the Cobalt Cartel, Michael Buchter, Peter Marshall, Herve Kelecom, Misha, Mark Heutlinger, Bonnie Cutler, John and Galina Mariani, Bennie (Bollag) and his Jets, Fredy Haemmerli, Wil Oosterhout, Christopher Dark, Eddie de Werk, Hubert Hutton, Fred Schwartz, Ira Sloan, Frank Wolstencroft, Congressman James Santini, John Culkin, Urs Aeby, Lynn Grebstad, Intertech Resources, the Kaypro Corporation, Harper’s magazine, Cambridge Metals, Redco v Acknowledgments [ e - reads] Resources, the Swire Group, ITR International, Philipp Brothers, the Heavy Metal Kids, and . -

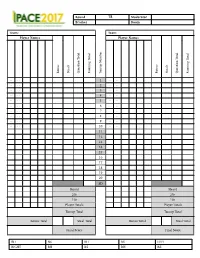

Round Moderator Bracket Room Team

Round 18 Moderator Bracket Room Team: Team: Player Names Player Names Steals Bonus Steals Question Total Running Total Bonus Running Total Tossup Number Question Total .. .. 1 .. .. .. .. 2 .. .. .. .. 3 .. .. .. .. 4 .. .. .. .. 5 .. .. .. .. 6 .. .. .. .. 7 .. .. .. .. 8 .. .. .. .. 9 .. .. .. .. 10 .. .. 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 SD Heard Heard 20s 20s 10s 10s Player Totals Player Totals Tossup Total Tossup Total Bonus Total Steal Total Bonus Total Steal Total Final Score Final Score RH RS BH BS LEFT RIGHT BH BS RH RS PACE NSC 2017 - Round 18 - Tossups 1. A small sculpture by this man depicts a winged putto with a faun's tail wearing what look like chaps, exposing his rear end and genitals. Padua's Piazza del Santo is home to a sculpture by this man in which one figure rests a hoof on a small sphere representing the world. His Atys is currently held in the Bargello along with his depiction of St. George, which like his St. Mark was originally sculpted for a niche of the (*) Orsanmichele. The equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius inspired this man's depiction of Erasmo da Narni. The central figure holds a large sword and rests his foot on a helmeted head in a sculpture by this artist that was the first freestanding male nude produced since antiquity. For 10 points, name this Florentine sculptor of Gattamelata and that bronze David. ANSWER: Donatello [or Donatello Niccolò di Betto Bardi] <Carson> 2. Minnesota Congressman John T. Bernard cast the only dissenting vote against a law banning US intervention in this conflict. Torkild Rieber of Texaco supplied massive quantities of oil to the winning side in this war. -

UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Petrodollar Era and Relations between the United States and the Middle East and North Africa, 1969-1980 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9m52q2hk Author Wight, David M. Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERISITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Petrodollar Era and Relations between the United States and the Middle East and North Africa, 1969-1980 DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by David M. Wight Dissertation Committee: Professor Emily S. Rosenberg, chair Professor Mark LeVine Associate Professor Salim Yaqub 2014 © 2014 David M. Wight DEDICATION To Michelle ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF TABLES v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi CURRICULUM VITAE vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION x INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The Road to the Oil Shock 14 CHAPTER 2: Structuring Petrodollar Flows 78 CHAPTER 3: Visions of Petrodollar Promise and Peril 127 CHAPTER 4: The Triangle to the Nile 189 CHAPTER 5: The Carter Administration and the Petrodollar-Arms Complex 231 CONCLUSION 277 BIBLIOGRAPHY 287 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1.1 Sectors of the MENA as Percentage of World GNI, 1970-1977 19 Figure 1.2 Selected Countries as Percentage of World GNI, 1970-1977 20 Figure 1.3 Current Account Balances of the Non-Communist World, 1970-1977 22 Figure 1.4 Value of US Exports to the MENA, 1946-1977 24 Figure 5.1 US Military Sales Agreements per Fiscal Year, 1970-1980 255 iv LIST OF TABLES Page Table 2.1 Net Change in Deployment of OPEC’s Capital Surplus, 1974-1976 120 Table 5.1 US Military Sales Agreements per Fiscal Year, 1970-1980 256 v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is a cliché that one accumulates countless debts while writing a monograph, but in researching and writing this dissertation I have come to learn the depth of the truth of this statement. -

The Treason of Rockefeller Standard Oil (Exxon) During World War II

The Treason Of Rockefeller Standard Oil (Exxon) During World War II By The American Chronicle February 4, 2012 We have reported on Wall Street’s financing of Hitler and Nazi programs prior to World War 2 but we have not given as much attention to its treasonous acts during the war. The depths to which these men of fabled wealth sent Americans to their deaths is one of the great untold stories of the war. John Rockefeller, Jr. appointed William Farish chairman of Standard Oil of New Jersey which was later rechristened Exxon. Farish lead a close partnership with his company and I. G. Farben, the German pharmaceutical giant whose primary raison d'etre was to occlude ownership of assets and financial transactions between the two companies, especially in the event of war between the companies' respective nations. This combine opened the Auschwitz prison camp on June 14, 1940 to produce artificial rubber and gasoline from coal using proprietary patents rights granted by Standard. Standard Oil and I. G. Farben provided the capital and technology while Hitler supplied the labor consisting of political enemies and Jews. Standard withheld these patents from US military and industry but supplied them freely to the Nazis. Farish plead “no contest” to criminal conspiracy with the Nazis. A term of the plea stipulated that Standard would provide the US government the patent rights to produce artificial rubber from Standard technology while Farish paid a nominal 5,000 USD fine Frank Howard, a vice president at Standard Oil NJ, wrote Farish shortly after war broke out in Europe that he had renewed the business relationship described above with Farben using Royal Dutch Shell mediation top provide an additional layer of opacity. -

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

Revista de Economía Institucional ISSN: 0124-5996 Universidad Externado de Colombia Braden, Spruille EL EMBAJADOR SPRUILLE BRADEN EN COLOMBIA, 1939-1941 Revista de Economía Institucional, vol. 19, núm. 37, 2017, Julio-Diciembre, pp. 265-313 Universidad Externado de Colombia DOI: https://doi.org/10.18601/01245996.v19n37.13 Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=41956426013 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto EL EMBAJADOR SPRUILLE BRADEN EN COLOMBIA, 1939-1941 Spruille Braden* * * * pruille Braden (1894-1978) fue embajador en Colombia entre 1939 y 1942, durante la presidencia de Eduardo Santos. Aprendió el español desdeS niño y conocía bien la cultura latinoamericana. Nació en Elkhor, Montana, pero pasó su infancia en una mina de cobre chilena, de pro- piedad de su padre, ingeniero de grandes dotes empresariales. Regresó a Estados Unidos para cursar su enseñanza secundaria. Estudió en la Universidad de Yale donde, siguiendo el ejemplo paterno, se graduó como ingeniero de minas. Regresó a Chile, trabajó con su padre en proyectos mineros y se casó con una chilena de clase alta. Durante su estadía sura- mericana no descuidó los vínculos políticos con Washington. Participó en la Conferencia de Paz del Chaco, realizada en Buenos Aires (1935-1936), y pasó al mundo de la diplomacia estadounidense, con embajadas en Colombia y en Cuba (1942-1945), donde estrechó lazos con el dictador Fulgencio Batista. -

Courtesy of Oral History Research Office Columbia University The

Courtesy of Oral History Research Office Columbia University The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History roject WILLIAM W. LEHFELDT Interviewed by: William Burr Initial interview date: April 29, 1987 Copyright Columbia niversity TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in California U.S. Army - World War II (eorgetown University and Harvard University Entered the Foreign Service Early Assignments Diplomatic courier 1,5. AID program - Afghanistan 1,52-1,55 Bilbao0 Spain - Consul 1,55-1,51 State Department - Washington0 DC 1,51-1,21 Buenos Aires0 Argentina - etroleum Officer 1,21 Cordova0 Argentina - Consul 1,22-1,23 State Department - Washington0 DC - ersonnel 1,23-1,22 Naples0 Italy - rincipal Officer 1,22-1,21 Economic Counselor - Teheran0 Iran 1,2,-1,13 Iran lan Organi5ation Embassy ersonnel and Duties Ambassador Douglas 6acArthur III Ambassador Farland - 1,12 Ambassador Helms - 1,13 Contacts in Iranian (overnment The Shah Economic Conditions U.S. policy towards Iran Ni8on diplomacy CIA operations U.S. interests 1 U.S. petroleum operations O EC Teheran Agreement - 1,11 9ohn Irwin mission Oil company negotiations with Iran St. 6orit5 Agreement - 1,12 Arab boycott of U.S. - 1,13 :Recycling: of oil country revenues U.S.-Iran 9oint Economic Commission Ni8on 1,12 visit U.S. military supplies U.S. banking presence Bankers' Conference Iran's economic situation - 1,2,-1,1. E8-Im Bank financing U.S. arms sales U.S. Embassy assistance Commercial :pay-offs: Shah's anti-corruption policy U.S.-Iran Chamber of Commerce U.S. concerned over Iran's arms spending Communications facilities (rowing criticism of Shah - internal and e8ternal Teheran0 Iran - Vice resident0 (eneral Electric 1,13-1,18 6ilitary aircraft Nuclear energy industry Investments in consumer products Iran-U.S. -

Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction Unexplored Facets of Naziism PART ONE: Wall Street Builds Nazi Industry Chapter One Wall Street Paves the Way for Hitler 1924: The Dawes Plan 1928: The Young Plan B.I.S. — The Apex of Control Building the German Cartels Chapter Two The Empire of I.G. Farben The Economic Power of I.G. Farben Polishing I.G. Farben's Image The American I.G. Farben Chapter Three General Electric Funds Hitler General Electric in Weimar, Germany General Electric & the Financing of Hitler Technical Cooperation with Krupp A.E.G. Avoids the Bombs in World War II Chapter Four Standard Oil Duels World War II Ethyl Lead for the Wehrmacht Standard Oil and Synthetic Rubber The Deutsche-Amerikanische Petroleum A.G. Chapter Five I.T.T. Works Both Sides of the War Baron Kurt von Schröder and I.T.T. Westrick, Texaco, and I.T.T. I.T.T. in Wartime Germany PART TWO: Wall Street and Funds for Hitler Chapter Six Henry Ford and the Nazis Henry Ford: Hitler's First Foreign Banker Henry Ford Receives a Nazi Medal Ford Assists the German War Effort Chapter Seven Who Financed Adolf Hitler? Some Early Hitler Backers Fritz Thyssen and W.A. Harriman Company Financing Hitler in the March 1933 Elections The 1933 Political Contributions Chapter Eight Putzi: Friend of Hitler and Roosevelt Putzi's Role in the Reichstag Fire Roosevelt's New Deal and Hitler's New Order Chapter Nine Wall Street and the Nazi Inner Circle The S.S. Circle of Friends I.G. Farben and the Keppler Circle Wall Street and the S.S. -

Wall Street Funding of the Rise of Hitler

WALL STREET FUNDING OF THE RISE OF HITLER Antony Suttons’ Investigation Of Wall Street Funding Of World War II FOR RESEARCH PURPOSES ONLY FROM THE LIBRARY OF DR. MICHAEL SUNSTAR 2007 SUNSTAR COMMENTARY ON THE WALL STREET FUNDING OF HITLER BY ANTONY SUTTON: A question that has been on the minds of lots of researchers on the rise of Hitler is: 1. How did Hitler obtain such advanced technology? 2. Although Hitler seized the German military system, who funded him and how did he come up with so many different types of armor, equipment and machinery? 3. Were there any American corporations involved with Nazi manufacturing and corporate financing and if so, which ones? 4. Was the devil truly in the details, and if so, which of his companies assisted Hitler? 5. From fighter planes in the air, to submarines under the ocean, to tanks, armory, weaponry, and sophisticated chemical warfare, just how did Hitler obtain so much access to so much technology in such a short period of time? 6. Why did the U.S. Government take so much time in responding to Hitler’s takeover of European nations? 7. Was there a Project Paperclip already in effect in Nazi Germany, before PROJECT PAPERCLIP was reported to be recruited in the United States after World War II? 8. Why was Hitler so angry against the Jewish people? Was it because of his discovery of the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion and was it because he found out about a plot among Masonic Jews to take over the world? Could he have been angry as he looked around Germany and saw the Jewish people prosperous & successful, while the German workers were suffering poverty? Was Hitler truly the bastard son of a Rothschild, as his mother worked for a Rothschild who fancied young women? 9. -

UNIVERISITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE the Petrodollar Era And

UNIVERISITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Petrodollar Era and Relations between the United States and the Middle East and North Africa, 1969-1980 DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by David M. Wight Dissertation Committee: Professor Emily S. Rosenberg, chair Professor Mark LeVine Associate Professor Salim Yaqub 2014 © 2014 David M. Wight DEDICATION To Michelle ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF TABLES v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi CURRICULUM VITAE vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION x INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The Road to the Oil Shock 14 CHAPTER 2: Structuring Petrodollar Flows 78 CHAPTER 3: Visions of Petrodollar Promise and Peril 127 CHAPTER 4: The Triangle to the Nile 189 CHAPTER 5: The Carter Administration and the Petrodollar-Arms Complex 231 CONCLUSION 277 BIBLIOGRAPHY 287 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1.1 Sectors of the MENA as Percentage of World GNI, 1970-1977 19 Figure 1.2 Selected Countries as Percentage of World GNI, 1970-1977 20 Figure 1.3 Current Account Balances of the Non-Communist World, 1970-1977 22 Figure 1.4 Value of US Exports to the MENA, 1946-1977 24 Figure 5.1 US Military Sales Agreements per Fiscal Year, 1970-1980 255 iv LIST OF TABLES Page Table 2.1 Net Change in Deployment of OPEC’s Capital Surplus, 1974-1976 120 Table 5.1 US Military Sales Agreements per Fiscal Year, 1970-1980 256 v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is a cliché that one accumulates countless debts while writing a monograph, but in researching and writing this dissertation I have come to learn the depth of the truth of this statement. -

Use of Theses

Australian National University THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. IRAN AS A REGIONAL MILITARY POWER (1970-78) Maqsud ul Hasan Nuri Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of International Relati The Australian National University September 1979 This thesis is my own original work. Maqsud Ail Hasan Nuri CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 IRAN'S THREAT PERCEPTIONS UNDER THE SHAH 6 THE IRANIAN ARMED FORCES - MAJOR DEFENCE AND NUCLEAR PROGRAMME 41 IRAN'S OCCUPATION OF THE GULF ISLANDS AND MILITARY INVOLVEMENT IN OMAN 67 IRAN-UNITED STATES MILITARY RELATIONSHIP 89 IRAN'S ARMAMENT PROGRAMME: A CRITIQUE 138 THE REVOLUTION OF 19 7 8-79: A CHANGE IN PERCEPTIONS 173 CONCLUSIONS 231 APPENDIX 1 238 APPENDIX 2 241 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 243 MAPS INTRODUCTION After 1970, Iran under the Shah started acquiring most of the attributes of a major regional power in the Persian Gulf region. As compared with its neighbours, it had a relatively larger population, a better developed techno-industrial base and a higher oil production rate (second only to Saudi Arabia). After the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, the excess of oil revenues as a result of the oil price increase was used to convert the Iranian oil wealth into a sizable military machine.