Dialogue on World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English-126.Pdf

2019 / 1398 ، بهار 126 ی شماره « آورد ره » ی فصلنامه 1 Page RAHAVARD Quarterly Persian & English Journal of Iranian Studies Issue 126, Spring 1398 / 2019 GOAL: Is to empowere our young generation with the richness of our Persian heritage, keep them informed of the history of the extraordinary people to whom they belong as they gain mighty wisdom from a western system that embraces them in the aftermath of the revolution and infuse them with the knowledge and ideals that inspire them. FINANCIAL: RAHAVARD is entirely supported by, Supscription dues, advertisers and RAHAVARD: contributions from its readers, and followers A Los Angeles-based Quarterly Bilingual who largely constitute the elite of the Iranians Journalof Iranian Studies, was founded by living in diaspora. HASSAN SHAHBAZ in 1981 in Los Angeles. DIGITAL RAHAVARD (ebook): In 2012 with the Rahavard, publishes scholarly articles in the encouragement & constant reminder of HOMA field of: Persian (Iranian) Studies (Literature, SARSHAR and Dr. FIROUZ NADERI RAHAVARD History, Politics, Culture, Society and beyond). English and Persian digital (ebook) was Its readers are well educated, well informed, launched as an online version of the publication business owners, scholars, intellectuals, at: www.rahavard.com. Since then it's appeal professors, politicians & philanthropists. has increased drastically, specifically by younger It's founder HASSAN SHAHBAZ passed away in generation and Iranians living in Iran. May 2006. Forming an Advisory Committee, ENGLISH RAHAVARD: In 2016 with the his widow Sholeh Shams Shahbaz has encouragements of H.E. ARDESHIR ZAHEDI, Dr. continued publishing. FIROUZ NADERI & the assistance of Dr. JANET Today, Rahavard has grown both in volume, AFARY, Cal State Santa Barbara (by providing subscription, and influence. -

Britain, British Petroleum, Shell and the Remaking of the International Oil Industry, 1957-1979

Empires of Energy: Britain, British Petroleum, Shell and the Remaking of the International Oil Industry, 1957-1979 Author: Jonathan Robert Kuiken Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104079 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2013 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of History EMPIRES OF ENERGY: BRITAIN, BRITISH PETROLEUM, SHELL AND THE REMAKING OF THE INTERNATIONAL OIL INDUSTRY, 1957-1979 [A dissertation by] JONATHAN R. KUIKEN submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2013 © copyright by JONATHAN ROBERT KUIKEN 2013 Empires of Energy: Britain, British Petroleum, Shell and the remaking of the international oil industry, 1957-1979 Jonathan R. Kuiken Dissertation Advisor - James E. Cronin Dissertation Abstract This dissertation examines British oil policy from the aftermath of the Suez Crisis in 1956-1957 until the Iranian Revolution and the electoral victory of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party in 1979. It was a period marked by major transitions within Britain’s oil policy as well as broader changes within the international oil market. It argues that the story of Britain, and Britain’s two domestically-based oil companies, BP and Shell, offers a valuable case study in the development of competing ideas about the reorganization of the international oil industry in the wake of the rise of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting countries and the companies’ losing control over the production of oil. -

Dynamics of Iranian-Saudi Relations in the Persian Gulf Regional Security Complex (1920-1979) Nima Baghdadi Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-22-2018 Dynamics of Iranian-Saudi Relations in the Persian Gulf Regional Security Complex (1920-1979) Nima Baghdadi Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC006552 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Baghdadi, Nima, "Dynamics of Iranian-Saudi Relations in the Persian Gulf Regional Security Complex (1920-1979)" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3652. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3652 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida DYNAMICS OF IRANIAN-SAU DI RELATIONS IN THE P ERSIAN GULF REGIONAL SECURITY COMPLEX (1920-1979) A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Nima Baghdadi 2018 To: Dean John F. Stack Steven J. Green School of International Relations and Public Affairs This dissertation, written by Nima Baghdadi, and entitled Dynamics of Iranian-Saudi Relations in the Persian Gulf Regional Security Complex (1920-1979), having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. __________________________________ Ralph S. Clem __________________________________ Harry D. -

July 16-31, 1973

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/22/1973 A Appendix “A” 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/27/1973 A Appendix “A” 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/29/1973 A Appendix “A” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-13 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary July 16, 1973 – July 31, 1973 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) _.- _.--. --------. THE: WHITE HOUSE PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON'S DAILY DIARY (See Travel Record for Trnel AdiYity) -P PLAcE DAY BEGAN DATE (No., bay, Yr.) JULY 16. 1973 NAVAL MEDICAL CENTER TlVI! DAY BETHESDA, MARYLAND 8:00 a.m. MONDAY PHONE TIME P=Pl.ctd R~Rcctiftcl ACTlVJTY la Oat 10 LD The President met with: 8:00 8:06 Robert J. Dunn, Chief Hospital Corpsman (HMC) 8:05 8:30 Susan A. -

Introduction of Domestic Reindeer Into Alaska

M * Vice-President Stevenson. Mrs. Stevenson. Governor and Mrs. Sheakley. Teachers and Pupils, Presbyterian Mission School, Sitka, Alaska. 54th Congress, SENATE. f Document 1st Session. \ No. 111. IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES. REPO R T ON WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS, MY SHELDON JACKSON, GENERAL AGENT OF EDUCATION IN ALASKA. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1896. CONTENTS. Page. Action of the Senate of the United States. 5 Letter of the Secretary of the Interior to the President of the Senate. 7 Report of Dr. Sheldon Jackson, United States general agent of education in Alaska, to the Commissioner of Education, on the introduction of domestic reindeer i nto A1 aska for 1895. 9 Private benefactions. 11 Appropriations of Congress. 13 Importation of Lapps. 14 Distribution of reindeer. 15 Possibilities of the future. 16 Effect upon the development of Alaska. 16 Disbursements. 18 APPENDIXES. Report of William Hamilton on the itinerary of 1895. 21 Annual report of William A. Kjellmann. 42 Trip to Lapland. 43 Arrival at Teller Reindeer Station. 54 Statistics of the herd.. 55 Fining a reindeer thief. 57 Breaking in deer. 60 The birth of fawns. 61 Milking. 63 Eskimo dogs. 63 Herders and apprentices. 65 Rations. 72 Reindeer dogs. 73 Harness. 75 The Lapps. 77 Sealing. 78 Fishing. 79 Eskimo herd. 80 Sickness. 82 School. 82 Buildings. 83 Police. 84 Christmas. 85 Skees. 85 Physician. 88 Fuel. 89 Annual report of W. T. Lopp, Cape Prince of Wales, herd... 91 Letter of J. C. Widstead to Dr. Sheldon Jackson. 93 Letter of Dr. Sheldon Jackson to Hon. W. -

Metal Men Metal Men Marc Rich and the $10 Billion Scam A

Metal Men Metal Men Marc Rich and the $10 Billion Scam A. Craig Copetas No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, scanning or any information storage retrieval system, without explicit permission in writing from the Author. © Copyright 1985 by A. Craig Copetas First e-reads publication 1999 www.e-reads.com ISBN 0-7592-3859-6 for B.D. Don Erickson & Margaret Sagan Acknowledgments [ e - reads] Acknowledgments o those individual traders around the world who allowed me to con- duct deals under their supervision so that I could better grasp the trader’s life, I thank you for trusting me to handle your business Tactivities with discretion. Many of those traders who helped me most have no desire to be thanked. They were usually the most helpful. So thank you anyway. You know who you are. Among those both inside and outside the international commodity trad- ing profession who did help, my sincere gratitude goes to Robert Karl Manoff, Lee Mason, James Horwitz, Grainne James, Constance Sayre, Gerry Joe Goldstein, Christine Goldstein, David Noonan, Susan Faiola, Gary Redmore, Ellen Hume, Terry O’Neil, Calliope, Alan Flacks, Hank Fisher, Ernie Torriero, Gordon “Mr. Rhodium” Davidson, Steve Bronis, Jan Bronis, Steve Shipman, Henry Rothschild, David Tendler, John Leese, Dan Baum, Bert Rubin, Ernie Byle, Steven English and the Cobalt Cartel, Michael Buchter, Peter Marshall, Herve Kelecom, Misha, Mark Heutlinger, Bonnie Cutler, John and Galina Mariani, Bennie (Bollag) and his Jets, Fredy Haemmerli, Wil Oosterhout, Christopher Dark, Eddie de Werk, Hubert Hutton, Fred Schwartz, Ira Sloan, Frank Wolstencroft, Congressman James Santini, John Culkin, Urs Aeby, Lynn Grebstad, Intertech Resources, the Kaypro Corporation, Harper’s magazine, Cambridge Metals, Redco v Acknowledgments [ e - reads] Resources, the Swire Group, ITR International, Philipp Brothers, the Heavy Metal Kids, and . -

Walking Tour

Visit Historic Main Street in Jackson The Heart of the Gold Country on Scenic Highways 88 & 49 FEATURING ANTIQUES • ART • BOOKS CRAFTS • FINE WINES GOURMET FOODS HISTORIC HOTEL & SALOON RESTAURANTS • 1 Amador County Museum 24 Wells Fargo Bank SERVICES • UNIQUE SHOPS 2 Jewish Synagogue Monument 25 Footbridge 3 The A. Fantozzi Marble Headstone Works 26 National Hotel 4 Jackson Protestant or Community Cemetery 27 12 Water Street 5 Historic Jewish Cemetery 28 Masonic Hall 6 Jackson Catholic Cemetery 29 Oddfellows’ Hall 7 St. Sava Serbian Orthodox Church 30 Add Art PLUS 8 The Hamilton Tract Victorian Subdivision 31 Rosebud’s Cafe 9 First Catholic Church Site 32 Celtic Knot 10 Early Town Rock Walls 33 Mother Lode Market 11 Fletcher Alley 34 Trassare Jewelry Store 12 Cafe DeCoco 35 Stecklers Building ANNUAL EVENTS 13 Globe Hotel Building 36 Old Jail Site 14 Jackson Cleaners Building 37 Native Son’s Hall COUNTY MUSEUM 15 Native Daughters’...Birthplace 38 Constitution Saloon KENNEDY GOLD MINE TOURS 16 Sidewalk Plaque 39 Toma & Associates 17 The Bottle Shop 40 Old Amador County Court House TAILING WHEELS PARK 18 41 Main Street 41 The Law Office & 19 Gold Mine Jewelers 42 St. Patrick’s Catholic Church & Rectory 20 35 Main Street 43 215 Court Street FRIENDLY PEOPLE 21 29-33 Main Street 44 The Jackson United Methodist Church 22 The Central Hotel 45 Parsonage, United Methodist Church 23 Trader Stan Bottileas, Jackson’s Creek Walking Tour Jackson – that city which gold, girls, gambling, When Amador was organized as a new county gastronomic delights and government has kept in 1854, Jackson eked out a win over Volcano to of lively for over 150 years – was born in the gold become the new county’s county seat. -

An Investigation Into British Neutrality During the American Civil War 1861-65

AN INVESTIGATION INTO BRITISH NEUTRALITY DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR 1861-65 BY REBECCA CHRISTINE ROBERTS-GAWEN A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MA by Research Department of History University of Birmingham November 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis sought to investigate why the British retained their policy of neutrality throughout the American Civil War, 1861-65, and whether the lack of intervention suggested British apathy towards the conflict. It discovered that British intervention was possible in a number of instances, such as the Trent Affair of 1861, but deliberately obstructed Federal diplomacy, such as the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. This thesis suggests that the British public lacked substantial and sustained support for intervention. Some studies have suggested that the Union Blockade of Southern ports may have tempted British intervention. This thesis demonstrates how the British sought and implemented replacement cotton to support the British textile industry. This study also demonstrates that, by the outbreak of the Civil War, British society lacked substantial support for foreign abolitionists’’ campaigns, thus making American slavery a poorly supported reason for intervention. -

Val Emmich ‘Slows It Down’ Upcoming Musician Is Emo’S Latest Voice of Rock Page 5 January 3, 2 0 0 5What’S Inside

MUSIC: ‘The Game’ revives west coast hip-hop MOVIE: Extreme DVD Full proves pain is universal FASHION: What to wear when you can’t find a thing in your closet EFFECTTitan Entertainment Guide The Hives shake things up at the House of Blues Val Emmich ‘slows it down’ Upcoming musician is emo’s latest voice of rock Page 5 January 3, 2 0 0 5What’S Inside Dave Muscato, an Apple fan, has opened www.freefi ona.com in an Contents attempt to make Sony release the album … 50 Cent has dropped the 02 News Briefs “Saint Valentineʼs Day” from his Calendar album title and is simply calling his sophomore effort “The Mas- 03 Movies- Are We There Yet sacre.” A video for the albumʼs Slammed second single “Candy Shop” will Flashback favorite-After be hitting the airwaves this week and the album will drop in March. School Specials Fans of System of a Down have 04 Music- The Hives two reasons to be thankful in 2005. The band will release “Hypno- Lassie Foundation tize,” featuring the single “Ciga- 05 The Game ro,” in late April and a second disc Columbia Pictures called “Mesmerize” in the sum- Val Emmich mer…Alex Garland who penned 06 Food-Brooklyn Pizza Works News Briefs of “How to Dismantle an Atomic “28 Days Later” has been tapped Book- He’s not that into you Bomb. to write “Saw 2” which will make 07 Fashion- Style Scout Head of The Inc., Irv Gotti Trent Reznor of Nine Inch itʼs way to theaters in late Octo- and his brother Chris, have been Nails announced that the bandʼs ber…Peter Jacksonʼs remake of charged with laundering more long awaited album, “With Teeth”, “King Kong,” which starts Naomi than $1 million in drug money which features drumming from Watts and Jack Black, has resumed through the record label. -

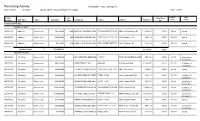

Permitting Activity 01/01/2018 Thru 10/14/2018 Date of Report: 10/15/2018 L-BUILD ONLY - Grouped by Type Then Subtype Page 1 of 295

Permitting Activity 01/01/2018 Thru 10/14/2018 Date of Report: 10/15/2018 L-BUILD ONLY - Grouped by Type then Subtype Page 1 of 295 Issued App. Permit Sq- Total Fees Date Status Number Sub Type Type Valuation Feet Contractor Owner Address Total Fees Due Commercial Permits: Addition Permits: LB1701130 Addition Commercial $92,900.00 1300 HAGGAI CONSTRUCTION &ST DEVELOPMENT PAULS BAPTIST INC CHURCH8002 Old Bainbridge Rd $1,803.31 $0.00 1/3/18 Issued LB1800208 Addition Commercial $20,000.00 400 GARRISON DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION,GARRISON DESIGN INC. & CONTRUCTION5186 Woodlane Cir $481.13 $0.00 5/22/18 Issued LB1801519 Addition Commercial $5,500.00 240 TONY E. COLVIN INC DBA SOUTHERNNEW JOURNEY FIXIN'S BAPTIST CHURCH4527 N Monroe St $135.40 $0.00 10/4/18 Issued Addition Totals: 3 $118,400.00 $2,419.84 $0.00 Alteration Permits: LB1602042 Alteration Commercial $22,000.00 SBA NETWORK SERVICES LLCT-MOBILE 5585 CRAWFORDVILLE RD $603.86 $0.00 2/2/18 Certificate of Completion LB1700443 Alteration Commercial $56,000.00 SIMPLERBUILT, INC. SABL LLC 5205 Mcneill Blvd $1,868.57 $0.00 3/12/18 Certificate of Completion LB1701599 Alteration Commercial $20,000.00 ATLANTIC TOWER SERVICES,LANG INC MARY ALMA TRUST 6017 Roberts Rd $648.41 $0.00 4/5/18 Issued LB1701639 Alteration Commercial $20,000.00 ASCEND WIRELESS NETWORKS,TYRE JANICE INC. L 5585 Crawfordville Rd $481.73 $0.00 1/18/18 Certificate of Completion LB1701744 Alteration Commercial $20,000.00 ASCEND WIRELESS NETWORKS,MOOSE INC. LODGE 1484 Capital Cir NW $621.56 $0.00 4/3/18 Certificate of Completion LB1701795 Alteration Commercial $228,920.00 LEDFORD DESIGN & CONSTRUCTION,FLEA MARKET LLC. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR FRAN OIS M. DICKMAN Interviewed by: Stanley Brooks Initial interview date: February 9, 2001 Copyright 2001 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in owa" raised in owa and Wyoming U.S. Army, World War " Korean War University of Wyoming" Fletcher School Brookings nstitution Entered Foreign Service - 19,1 Barran-uilla, .olombia - 0ice .onsul 19,1-19,1 2eporting Environment Washington, D. - FS - Arabic 3anguage Training 19,1-19,, Beirut, 3ebanon - FS - Arabic 3anguage Training 19,4-19,7 Environment Sue6 .anal nationali6ation .ourse of instruction Khartoum, Sudan - .onsular7Economic Officer 19,7-1940 Unity .otton Nile waters A D Travel State Department Office of Near East Affairs - Economic Affairs 1940-1941 Arab boycott of srael Sue6 .anal State Department - UA2 Desk Officer 1941-194, Non-aligned movement Nasser Belgrade .onference 1 Syria-Egypt union ends U.S. missiles to srael P3 180 for Egypt North Yemen-Egypt Yemen 2epublicans Egyptian-Saudi relations Egypt=s missiles Dimona .ANE (.ontrol of Arms Near East) Mc.loy Middle East missions Abu Simbel US S .airo library burned Syria Margaret=s activities Tunis, Tunisia - Economic officer 194,-1948 French Nationali6ation Economy P3 180 A D Arab- srael 1947 war Embassy attacked President Bourguiba Environment Margaret=s activities Army War .ollege (.arlisle, Pennsylvania) 1948-1949 Aeddah, Saudi Arabia - Economic7Political Officer 1949-1972 Environment Aidda-2iyadh BshuttleC Deterrent Force North Yemen A2AM.O OPE. Shah of ran 3ondon Droup Military e-uipment Aoseph Kraft Arabists Oman Desalination plant State Department - Arabian Peninsula - .ountry Director 1972-1974 Arab Emirates 2 Dulf States PD2Y Persian Dulf ran Saudi-U.S. -

![[ 1967 ] Appendices](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7016/1967-appendices-1467016.webp)

[ 1967 ] Appendices

APPENDIX I ROSTER OF THE UNITED NATIONS (As at 31 December 1967) DATE OF ADMIS- DATE OF ADMIS- MEMBER SION TO U.N. MEMBER SION TO U.N. Afghanistan 19 Nov. 1946 Hungary 14 Dec. 1955 Albania 14 Dec. 1955 Iceland 19 Nov. 1946 Algeria 8 Oct. 1962 India 30 Oct. 1945 Argentina 24 Oct. 1945 Indonesia1 28 Sep. 1950 Australia 1 Nov. 1945 Iran 24 Oct. 1945 Austria 14 Dec. 1955 Iraq 21 Dec. 1945 Barbados 9 Dec. 1966 Ireland 14 Dec. 1955 Belgium 27 Dec. 1945 Israel 11 May 1949 Bolivia 14 Nov. 1945 Italy 14 Dec. 1955 Botswana 17 Oct. 1966 Ivory Coast 20 Sep. 1960 Brazil 24 Oct. 1945 Jamaica 18 Sep. 1962 Bulgaria 14 Dec. 1955 Japan 18 Dec. 1956 Burma 19 Apr. 1948 Jordan 14 Dec. 1955 Burundi 18 Sep. 1962 Kenya 16 Dec. 1963 Byelorussian SSR 24 Oct. 1945 Kuwait 14 May 1963 Cambodia 14 Dec. 1955 Laos 14 Dec. 1955 Cameroon 20 Sep. 1960 Lebanon 24 Oct. 1945 Canada 9 Nov. 1945 Lesotho 17 Oct. 1966 Central African Republic 20 Sep. 1960 Liberia 2 Nov. 1945 Ceylon 14 Dec. 1955 Libya 14 Dec. 1955 Chad 20 Sep. 1960 Luxembourg 24 Oct. 1945 Chile 24 Oct. 1945 Madagascar 20 Sep. 1960 China 24 Oct. 1945 Malawi 1 Dec. 1964 Colombia 5 Nov. 1945 Malaysia2 17 Sep. 1957 Congo (Brazzaville) 20 Sep. 1960 Maldive Islands 21 Sep. 1965 Congo, Democratic Republic of the 20 Sep. 1960 Mali 28 Sep. 1960 Costa Rica 2 Nov. 1945 Malta 1 Dec. 1964 Cuba 24 Oct. 1945 Mauritania 27 Oct.