Seed Security in Badakshan, Afghanistan Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

·~~~I~Iiiiif~Imlillil~L~Il~Llll~Lif 3 ACKU 00000980 2

·~~~i~IIIIIf~imlillil~l~il~llll~lif 3 ACKU 00000980 2 OPERATION SALAM OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS CO-ORDINATOR FOR HUMANITARIAN AND ECONOMIC ASSISTANCE PROGRAMMES RELATING TO AFGHANISTAN PROGRESS REPORT (JANUARY - APRIL 1990) ACKU GENEVA MAY 1990 Office of the Co-ordinator for United Nation Bureau du Coordonnateur des programmes Humanitarian and Economic Assistance d'assistance humanitaire et economique des Programmes relating to Afghanistan Nations Unies relatifs a I 1\fghanistan Villa La Pelouse. Palais des Nations. 1211 Geneva 10. Switzerland · Telephone : 34 17 37 · Telex : 412909 · Fa·x : 34 73 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD.................................................. 5 SECTORAL OVERVIEWS . 7 I) Agriculture . 7 II) Food Aid . 7 Ill) De-m1n1ng . 9 IV) Road repair . 9 V) Shelter . 10 VI) Power . 11 VII) Telecommunications . 11 VI II) Health . 12 IX) Water supply and sanitation . 14 X) Education . 15 XI) Vocational training . 16 XII) Disabled . 18 XIII) Anti-narcotics programme . 19 XIV) Culture . ACKU. 20 'W) Returnees . 21 XVI) Internally Displaced . 22 XVII) Logistics and Communications . 22 PROVINCIAL PROFILES . 25 BADAKHSHAN . 27 BADGHIS ............................................. 33 BAGHLAN .............................................. 39 BALKH ................................................. 43 BAMYAN ............................................... 52 FARAH . 58 FARYAB . 65 GHAZNI ................................................ 70 GHOR ................... ............................. 75 HELMAND ........................................... -

Gericht Entscheidungsdatum Geschäftszahl Spruch Text

13.03.2018 Gericht BVwG Entscheidungsdatum 13.03.2018 Geschäftszahl W114 2178798-1 Spruch W114 2178798-1/10E schriftliche Ausfertigung des am 26.02.2018 mündlich verkündeten Erkenntnisses: IM NAMEN DER REPUBLIK! Das Bundesverwaltungsgericht hat durch den Richter Mag. Bernhard DITZ über die Beschwerde von XXXX , geb. am XXXX , Staatsangehörigkeit Afghanistan, vertreten durch ARGE Rechtsberatung - Diakonie und Volkshilfe, gegen den Bescheid des Bundesamtes für Fremdenwesen und Asyl vom 31.10.2017, Zl. 1098450806-151965996/BMI-BFA_STM_RD, nach Durchführung einer mündlichen Verhandlung am 26.02.2018 zu Recht erkannt: A) Die Beschwerde wird gemäß §§ 3 Abs. 1, 8 Abs. 1, 10 Abs. 1 Z 3, 55, 57 AsylG 2005, § 9 BFA-VG, und §§ 52, 55 FPG als unbegründet abgewiesen. B) Die Revision ist gemäß Art. 133 Abs. 4 B-VG nicht zulässig. Text ENTSCHEIDUNGSGRÜNDE: I. Verfahrensgang: 1. XXXX (im Weiteren: Beschwerdeführer oder BF) reiste gemeinsam mit seinem Bruder XXXX illegal in das österreichische Bundesgebiet ein und stellte am 10.12.2015 einen Antrag auf internationalen Schutz. 2. Am selben Tag fand vor einem Organ des öffentlichen Sicherheitsdienstes die niederschriftliche Erstbefragung des Beschwerdeführers statt. Dabei gab er an, dass er im Alter von ca. einem Jahr gemeinsam mit seiner Familie Afghanistan wegen des Krieges in Afghanistan verlassen habe. Die Familie habe dann 18 - 19 Jahre illegal im Iran gelebt. Er wisse nicht, wo sich seine Eltern und seine Schwester in den letzten beiden Jahre aufgehalten hätten. Er habe mit seinem Bruder illegal im Iran gelebt. Er habe Angst vor einer Abschiebung nach Afghanistan gehabt. Da er in Afghanistan keine engen Angehörigen habe, habe er sich im November 2015 entschieden, mit seinem Bruder nach Österreich zu flüchten. -

ERM Household Assessment Report

ERM Household Assessment Report Assessment Location: Faizabad,Zebak.shughnan district’s Badakhshan province Type of crises: Armed Conflict between AOGs and ANSFs Crisis Location: Zebak, Shawa shughans’ district. Assessment Team: ACTED, WFP/IDS.DoRR. DACAAR, FOCUS,DoRR Crisis date: 13/7/ 2018 Date of Notification: 16/7/2018 Date of Assessment: 21/24/July/2018 HHs: Families: Inds: Affected Population: 46 46 166 Electronic Hardcopy Data collection method X Briefly Assessment report from incidents On date of 13-7-2018 AOG Attacked to police check points at Gul Khanna and Tazab villages ’in zebak district which caused displacement of families to Zebak and Ishakshim district of Badakhshan. At the same time AOG also warn to the residents of Shughnia villages in Sheghnan district to leave the area and escaped to some other location, then the people displaced from insecure locations to center of Sheghnan district. Most of the people who were displaced to Zebak district upon situation got normal they returned back to their original places and only some of the families were remained in Zebak district which has been assessed by JAT. As a result the residing of Zebak and Shewa shughnia districts’ displaced in different place or different districts’ from Shewa shughnia 6 families came to Faizabad and 33 families moved to Shughnan district. the total displaced families in Shewa shughnia villages are 39 families which was displaced by Taliban warnin, and 49 families displacement from zebak but 42 families retuned and 7 families was still displaced in Center zebak in ishkashim district, ACTED received notification regarding this displacement on 16-7-2018 which after that UN-OCHA called the agencies for an OCT meeting regarding this caseload on 18.7.2018 and established three joint assessment teams to quickly assess these families, the teams were consisting of DoRR ,DCAAR,IDS,/WFP, ACTED. -

Badakhshan Operational Coordination Team (OCT) Meeting

Badakhshan Operational Coordination Team (OCT) meeting WFP Faizabad hall Tuesday 16 July 2018, 09; 00 am Participants; SFL, DACAAR, UNHCR, ACTED, WFP, NAC, DoRR, Afghan Aid, BVWO, FOCUS, ME, ARCS and UNOCHA # Agenda Discussions Action points 1 Welcome and introduction OCHA warmly welcomed the team and the team introduced themselves to each other. Updates on conflict IDPs ACTED: during the month of May and June 827 families were passed in Badakhshan WFP will provide food items, conflict IDPs screening committee meetings to be assessed the joint assessment teams 2 assessment and responses in UNHCR provides NFI and were led by ACTED assessed the mentioned families and still assessment is ongoing in Badakhshan provincial level. Baharak districts; DACAAR provides hygiene kits Month of May: 399 families were selected to be assessed in Faizabad and Keshem for the 98 conflict IDPs of districts the mentioned families were displaced from different parts of Badakhshan province. out of 399 the team found only 60 families and the rest returned back to their Raghistan, Kohistan and home villages and they have been responded. Yawan districts. On 28 June in Badakhshan conflict IPDs screening committee meeting the team selected 428 families and 3 teams deployed, the assessment finished in Faizabad the team have NAC and Concern WW will visited 64 families and verified 36 families as real IDPs. facilitate with them to find Assessment is still ongoing and we will start assessment in Baharak district but security situation is not good in Baharak district we will try to assess but our team feel risk. beneficiaries in the mentioned The team agreed that DoRR will contact the Baharak district governor to get information districts. -

Regional Level Coordination Arrangements FSAC Is Active in 5 Regions out of 6 from Fall 2012

Field Consultation-Faizabad Regional level coordination arrangements FSAC is active in 5 regions out of 6 from fall 2012. Regular meetings held in Mazar-e-Sharif, Hirat, Jalalabad, Faizabad, Kandahar and Kabul. WFP, FAO or another agency (NGO, DAIL) chair the FSAC coordination meetings at regional levels. The FSAC acts as a forum for an open discussion on current food security and agricultural issues, sharing of ideas and best practices, and advocacy for the sector. Meetings are held on a regular basis, and are attended by a variety of stakeholders, including Government officials, NGOs, donors and UN Agencies. It is worth to be mentioning that the regional coordination mechanism in south region has been inactive since March 2014, it need to be re-activated in the region. Objective of field consultation . Consultation with partners to identify changes in humanitarian needs. To design Humanitarian Program Cycle (HPC) based on HNO. To Assess coordination needs & current arrangement List of Participants Total 19 participants (14 partners) attended: WFP, FOCUS, UNEP, WMSSO, Rupani Foundation, DAIL of Takhar, ACTED, DAIL Badakhshan, Afghanaid, UNAMA, SFL, RCWO, Mission East, FAO and FSAC Kabul. Situation overview Food security situation in North East Region . The upcoming harvest was estimated to be normal for majority of Northeastern region (except a few cold climate areas) during field consultation partners reported that rust and fungus affected wheat harvest, about 80% land affected in Badakhshan (20 districts), which has caused considerable reduction in harvest in cold climate areas of the province. Due to long-lasting rainfalls in spring time during 2014/2015, farmers in upper/cold climate areas of Badakhshan province cultivated their rain-fed lands later than normal and couldn’t harvest before snowfall, therefore in the last two years the lean season in those areas were longer than normal and issues of food gaps were reported. -

Afghan Ista N

Integrated Nutrition, Mortality Health, WASH and FSL SMART Survey Final Report Badakhshan Province, Afghanistan 30th July to 15th August 2018 AFGHANISTAN Survey Manger: Dr. Baidar Bakht Habib Authors: Dr. Shafiullah Samim and Dr. Mohammad Nazir Sajid Funded by: Action Against Hunger | Action Contre La Faim A non-governmental, non-political and non-religious organization 1 Acknowledgments The authors would like to pass their sincere appreciation to the Action Against Hunger/Action Contre la Faim (ACF) team in Kabul and Paris Headquarter. Special appreciation goes to the Care of Afghan Familles (CAF) team in Kabul and Badakhshan province. Finally yet importantly tremendous appreciation goes to the following stakeholders: Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) especially Public Nutrition Department (PND), AIM-Working Group and Nutrition Cluster for their support and validation of survey protocol. Badakhshan Provincial Public Health Directorate (PPHD) and the Provincial Nutrition Officer (PNO) for their support and authorization. Office for the coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) for their financial support in the survey. All the community members for welcoming and support the survey teams during the data collection process. Survey teams composed of enumerators, team leaders and supervisors for making the entire process smoothly. Statement on Copyright © Action Against Hunger Action Against Hunger is a non-governmental, non-political and non-religious organization. Unless otherwise indicated, reproduction is authorized on condition that the source is credited. If reproduction or use of texts and visual materials (sound, images, software, etc.) is subject to prior authorization, such authorization was render null and void the above-mentioned general authorization and was clearly indicate any restrictions on use. -

2.3 Afghanistan Road Network

2.3 Afghanistan Road Network Overview Road Security Weighbridges and Axle Load Limits Road Class and Surface Conditions Afghanistan Road Network Regional Information Northern Region North Eastern Region Central Region Western Region Primary Roads Overview Page 1 The Ministry of Public Works (MPW) and Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development (MRRD) are responsible for development, management and maintenance of Afghanistan roads. Road Classification Length (km) National Highways 3,363 km Regional Highways 4,884 km Provincial Roads 9,656 km Rural Roads (unpaved) 17,000 km As a result of decades of conflict, the road network was largely destroyed. Since 2002, Afghanistan has launched major programmes for improving its road network with the help of various international partners. The Government is implementing the National Emergency Rural Access Project (NERAP) and National Rural Access Programme (NRAP) provide the construction and rehabilitation of rural roads. Highway 1 or A01, formally called the Ring Road, is a 2,200 kilometre two-lane road network circulating inside Afghanistan connecting the following major cities (clockwise): Mazar, Kabul, Ghazni, Kandahar, Farah and Herat. It has extensions that also connect Jalalabad, Lashjkar Gah, Delaram, Islam Qala and several other cities. It is part of AH1, the longest route of the Asian Highway Network. Part of Highway 1 has been refurbished since late 2003, particularly the Kabul-Kandahar, with funds provided by the USA, KSA and others. Most work on that stretch was done by Turkish, Indian and local companies. Japanese companies were also involved near the southern Afghan province of Kandahar. In the west, Iran participated in the two-lane road construction between Islam Qala and the western Afghan city of Herat. -

The Non-Pashtun Taleban of the North (1): a Case Study from Badakhshan

The Non-Pashtun Taleban of the North (1): A case study from Badakhshan Author : Obaid Ali Published: 3 January 2017 Downloaded: 4 September 2018 Download URL: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/the-non-pashtun-taleban-of-the-north-a-case-study-from-badakhshan/?format=pdf The Taleban movement is winning ground in the northern province of Badakhshan, a province that was never conquered when the Taleban were in power in the 1990s. Over the past two years, a new generation of largely Tajik Taleban has come to pose a serious challenge for the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) : a number of districts have changed hands between the ANSF and insurgents, and two strategic districts are now insurgent strongholds. Its success seems partly due to a recruitment policy that – in contrast to the 1990s – favours local non-Pashtuns for key provincial positions and as fighters. In this provincial case study, AAN’s Obaid Ali analyses the Taleban’s new recruitment policy and how it has strengthened the movement (with input from Borhan Osman and Thomas Ruttig). In 2004, as the insurgency began to gather pace, setting up a shadow administration was one of the Taleban’s major political strategies for controlling both territory and population. Over the years, in the Tajik and Uzbek-dominated provinces in the north, the movement increasingly 1 / 7 appointed local non-Pashtuns, from shadow governors – both at the provincial and district level – to judges and heads of provincial committees. In Badakhshan, a Tajik-dominated province, most Taleban posts are now occupied by Tajiks. The shift in the movement’s recruitment strategy seems to have had a visible impact on its battlefield gains in Badakhshan. -

The Mineral Industry of Afghanistan in 2015

2015 Minerals Yearbook AFGHANISTAN [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior December 2018 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of Afghanistan By Karine M. Renaud Afghanistan has a wide range of mineral resources, including in Takhar Province, and mining for gemstones in Badakhshan metals, industrial minerals, and mineral fuels and related Province (Global Cement, 2015a). materials. In recent years, deterioration of the security situation, political uncertainty, and a lack of infrastructure had prevented Government Policies and Programs the country’s development of most of these resources. In 2015, The Ministry of Mines and Petroleum (MOMP) is the the minerals mined in Afghanistan included aragonite, chromite, main entity responsible for the administration of mining coal, fluorspar, gypsum, lime, marble, natural gas, petroleum, policy and for oversight and regulation of the mining sector, salt, and precious and semiprecious stones. The mineral- including mineral exploration and exploitation. The MOMP processing industry produced cement and iron and steel (table 1; has several subagencies, including the Afghanistan Geological International Monetary Fund, 2016, p. 4). Survey (AGS), the Afghanistan Petroleum Authority, and Minerals in the National Economy the Inter-Ministerial Committee. The Mining Revenue Management Policy ensures that the revenue generated from Afghanistan’s real gross domestic product (GDP) increased mining is allocated to designated sectors. The Mineral Cadastre by 0.8% in 2015 compared with an increase of 1.3% (revised) Department accepts and processes applications for mineral in 2014; the nominal GDP was $19.00 billion. The rate of rights, coordinates their technical and environmental evaluation, decrease was owing to ongoing challenges, such as political processes renewals, and collects application and surface right instability, the uncertain security situation, the withdrawal of fees. -

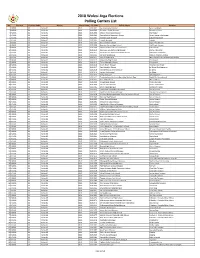

2018 Wolesi Jirga Elections Polling Centers List

2018 Wolesi Jirga Elections Polling Centers List No Province Province Code District District Code PC_Code * Polling Center Location 1 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101001 Sar e Gardana Mosque Sar e Gardanah 2 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101002 Derakht e Shing Mosque Darakht e Shing 3 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101003 Mullah Mahmood Mosque Shor Bazar 4 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101004 Daqiqi Balkhi Secondary School Saraji, Kocha e Aahengari 5 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101005 Aakhir e Jada Mosque Jadah e Maiwand 6 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101006 Eidgah Mosque Eidgah 7 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101007 Ansuri Balkhi School Bagh e Ali Mardan 8 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101008 Aayesha Durani High School Pul E bagh Umomi 9 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101009 Mastoori Ghoori Secondary School Babai Khudi 10 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101010 Aasheqan wa Arefan High School Kocha e Achakzai 11 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101011 Aasheqan wa Arefan Secondary School SehDukan Chindawal 12 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101012 Sar e Karez Mosque Bala Joi Asheqan Arefan 13 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101013 Bala Qilla Mosque Masjid e Bala Qilla Asheqan wa Arefan 14 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101014 Mahjooba High School Chindawal 15 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101015 Takya Khanahh Jafarya Chindawal 16 KABUL 01 Nahia 01 0101 0101016 Imam Baqer Mosque Hazaraha ha village 17 KABUL 01 Nahia 02 0101 0101017 Qari Abdullah School Joi Sheer Deh Afghanan 18 KABUL 01 Nahia 02 0101 0101018 Hazrat Nabawi Jame Mosque Joi Sheer 19 KABUL 01 Nahia 02 0101 0101019 Ansari High School Joi Sheer 20 KABUL 01 Nahia 02 0101 0101020 -

The Mineral Industry of Afghanistan in 2017-2018

2017–2018 Minerals Yearbook AFGHANISTAN [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior December 2020 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of Afghanistan By Karine M. Renaud Note: In this chapter, information for 2017 is followed by information for 2018. Afghanistan has deposits of bauxite, copper, iron, lithium secondary steel, by 38%; coal, by 24%; and natural gas, by 13% (spodumene), and rare-earth minerals. In 2017, minerals mined in 2017. Production of salt (rock) decreased by 42%; cast iron in Afghanistan included chromite, coal, fluorspar, gypsum, and lime, by 15% each; and crushed marble, by 6% (table 1; lime, marble, natural gas, petroleum, salt, and precious Central Statistics Organization, 2017, p. 206). and semiprecious stones. The mineral-processing industry produced cement and secondary steel. In recent years, however, Structure of the Mineral Industry deterioration of the security situation, political uncertainty, In 2017, such mineral resources as chromite, coal, gypsum, and a lack of infrastructure prevented the development of most lime, marble, natural gas, salt, precious and semiprecious stones, of these resources. According to the Afghan Anti-Corruption and talc continued to be extracted through artisanal and small- Network, local warlords, insurgents, and local people continued scale mining. In 2017, the MoMP posted 979 mine contracts on to mine some of those mineral resources in Afghanistan its website, the majority of which were expired or cancelled. illegally. In 2017, gemstones, marble, semiprecious stones, and Table 2 is a list of major mineral facilities operating in 2017 talc continued to be smuggled from Afghanistan to Pakistan and (Ministry of Mines and Petroleum, 2018). -

Briefing Notes 15 May 2017

Group 22 – Information Centre Asylum and Migration Briefing Notes 15 May 2017 Afghanistan Armed clashes Fights are continuing, with cleansing campaigns and raids carried out by the security forces as well as attacks and assaults by the insurgents, in which civilians are killed or wounded. According to press reports, the following provinces were affected during the last week: Kandahar, Helmand, Zabul (south), Farah, Herat (west), Samangan (north: here, Taliban insurgents were trying to take control of the coalmines in Dara-i-Suf Bala district), Faryab (north), Nangarhar (east), Kunduz (northeast) und Badakhshan (northeast; government officials say that Zebak district has been recaptured from the Taliban). In Barmal district of southeastern Paktika province, new fights have erupted between Afghan and Pakistani security forces (see BN of 8 May 2017). Attacks and assaults On 7 and 8 May 2017, four individuals were targeted in deadly attacks in the southern city of Kandahar. The victims were a staff member of the police headquarters, a police officer, a soldier and a media advisor of the provincial government. On 9 May, a bomb attack killed the head of the Ulema Council (Afghanistan’s highest religious body) together with seven of his students in central Parwan province. In western Farah province, a police officer was shot dead. In eastern Kunar, the head of the IS recruiting campaign was arrested. In eastern Nangarhar, three civilians were injured in a bomb explosion. On 10 May, a road bomb detonated in southern Helmand province, killing one civilian and wounding four others. A similar incident in western Herat province claimed the lives of seven civilians, among them women and children.